New Deal Opposition

Roosevelt’s Critics

By 1935, Roosevelt’s programs were provoking strong opposition. Many conservatives regarded his programs as infringements on the rights of the individual, while a growing number of critics argued that they did not go far enough. Three figures stepped forward to challenge Roosevelt: Huey Long, a Louisiana senator, Father Charles Coughlin, a Catholic priest from Detroit, and Francis Townsend, a retired California physician.

Of the three, Huey Long attracted the widest following. Ambitious, endowed with supernatural energy, and totally devoid of scruples, Long was a fiery, spellbinding orator in the tradition of Southern Populism. As governor and then U.S. senator, he ruled Louisiana with an iron hand, keeping a private army equipped with sub-machine guns and a “deduct box,” where he kept funds deducted from state employees’ salaries. Yet the people of Louisiana loved him because he attacked the big oil companies, increased state spending on public works, and improved public schools. Although he backed Roosevelt in 1932, Long quickly abandoned the president and opposed the New Deal as too conservative.

Huey Long was immensely popular, especially among the poor. Part of his appeal lay in his style; he dressed in vanilla ice cream-white suits and called himself “the Kingfish,” after a character in “Amos ‘n Andy.” He became a popular legend by playing up his country origins and ridiculing the rich. In one incident, he issued a “budget” showing how millionaires could economize by living on $10,000 a day.

Early in 1934, Long announced his “Share Our Wealth” program. Vowing to make “every man a king,” he promised to soak the rich by imposing a stiff tax on inheritances over $5 million and by levying a 100 percent tax on annual incomes over $1 million. The confiscated funds, in turn, would be distributed to the people, guaranteeing every American family an annual income of no less than $2,000. In Long’s words, the money would be more than enough to buy “a radio, a car, and a home.” By February 1935, Long’s followers had organized over 27,000 “Share Our Wealth” clubs. Roosevelt had to take him seriously, for a Democratic poll revealed that Long could attract three-to-four million voters to an independent presidential ticket.

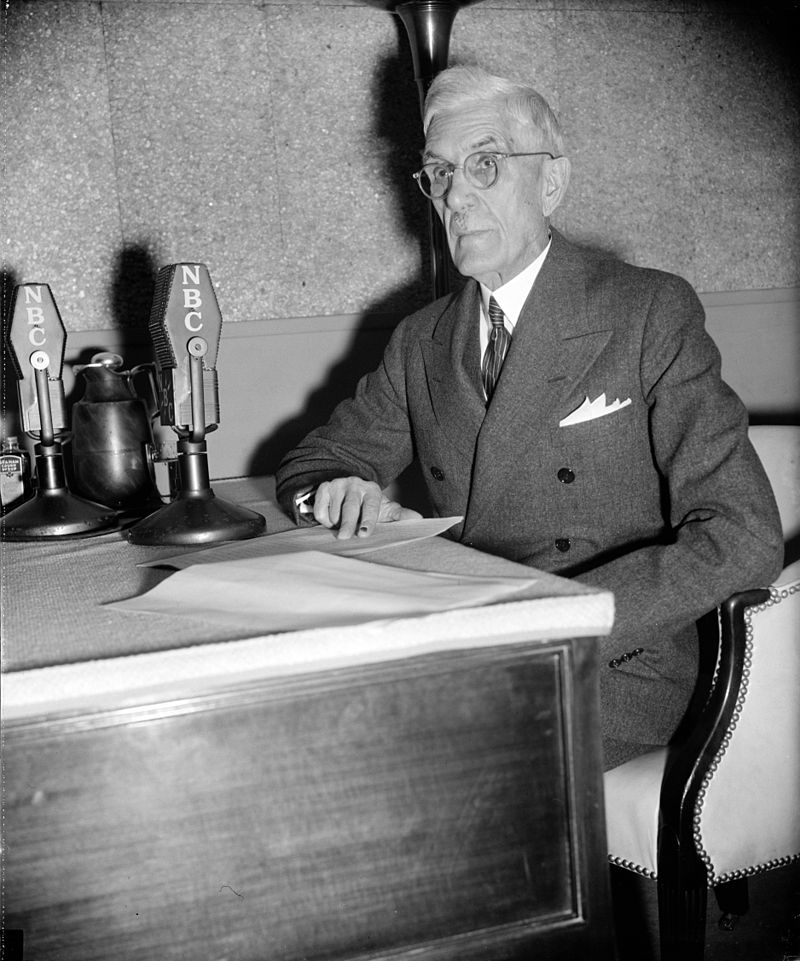

Like Long, Father Charles Coughlin was an early supporter who turned sour on the New Deal. For about sixteen years, from the mid-1920s until the United States entered World War II, Father Charles Coughlin was probably the most influential religious figure in the United States. His radio program, “The Golden Hour of the Shrine of the Little Flower,” had a weekly audience of sixteen million. His parish in suburban Detroit had to build a post office to handle his mail.

Coughlin blamed the Depression on greedy bankers and challenged Roosevelt to solve the crisis by nationalizing banks and inflating the currency. When Roosevelt refused to heed his advice, Coughlin broke with Roosevelt and in 1934 formed the National Union for Social Justice. The National Union’s weekly newspaper serialized “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” an anti-Semitic forgery.

Father Coughlin helped to invent a new kind of preaching that made effective use of the microphone and radio. Coughlin exemplified what historian Richard Hofstadter called the “paranoid style.” He believed that Jews and Communists, in league with bankers and capitalists, were out to get the little man.

Roosevelt’s least likely critic was Dr. Francis Townsend, a California public health officer, who found himself unemployed at the age of 67 with only $100 in savings. Seeing many people in similar or worse straits, Townsend embraced old-age relief as the key to ending the Depression.

In January 1934, Townsend announced his plan, demanding a $200 monthly pension for every citizen over the age of sixty. In return, recipients had to retire and spend their entire pension every month within the United States.

Younger Americans would inherit the jobs vacated by senior citizens and the economy would be stimulated by the increased purchasing power of the elderly. Although critics lambasted the Townsend plan as ludicrous, several million Americans found his plan refreshingly simple.

The Wagner Act

In 1932, George Barnett, a prominent economist and president of the American Economics Association, forecasted a bleak future for organized labor. “The changes, occupational and technological, which checked the advance of unionism in the last decade, appear likely to continue in the same direction,” he intoned.

In 1930, only 3.4 million workers belonged to labor unions—down from 5 million in 1920. Union members were confined to a few industries, such as construction, railroads, and local truck delivery. The nation’s major industries, like autos and steel, remained unorganized.

In 1935, Congress passed the landmark Wagner Act (the National Labor Relations Act), which spurred labor to historic victories. The act guaranteed private sector employees the right to organize into trade unions, and forbade companies from engaging in unfair labor practices.

A sit-down strike by auto workers in Flint, Michigan in 1937 led General Motors to recognize the United Automobile Workers. Union membership soared from 3.4 million in 1932 to 10 million in 1942 and to 16 million in 1952.

Bitter labor-management warfare erupted as the Depression dragged on. In 1934, some 1.5 million workers went on strike. Auto and steel workers and longshoremen became involved in violent strikes. Police shot 67 striking Teamsters in Minneapolis. In August, textile workers staged the largest strike the country had ever seen—a total of 500,000 workers in twenty states. In Massachusetts alone, 110,000 workers went on strike, and 60,000 workers in Georgia struck. While some of the strikes aimed at higher wages, a third demanded union recognition.

Labor unrest forced the federal government to step into labor relations and to forge a compromise between management and labor. Under the Wagner Act of 1935, the federal government guaranteed the right of employees to form unions and to bargain collectively. It also set up the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), which had the power to prohibit unfair labor practices by employers.

Three years later, Congress enacted another key piece of labor legislation. The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 established a minimum wage, as well as “time-and-a-half” overtime pay for those working more than 40 hours a week. The act also prohibited most forms of child labor.

During the mid-1930s, a bitter dispute broke out within labor’s ranks. It involved an issue that had been simmering for half a century: Should labor focus its efforts on unionizing skilled workers; or should labor unionize all workers in industry, regardless of skill level? The country’s major labor federation, the American Federation of Labor, consisted of craft unions organized by occupation. In late 1935, a group of union leaders, including John L. Lewis of the United Mine Workers, David Dubinsky of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers, and Sidney Hillman of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers, formed the Committee of Industrial Organization (CIO) to organize unskilled workers in America’s mass production industries. The CIO formed unions in the auto, glass, radio, rubber, and steel industries, and by the end of 1937, it had more members than the American Federation of Labor (AFL)—3.7 million CIO members against 3.4 million AFL members.

The 44-day sit-down strike in Flint, Michigan forced General Motors to recognize the United Auto Workers. A few weeks later, U.S. Steel accepted unionization without a strike, but the “Little Steel” companies, Bethlehem, Inland, National, Republic, and Youngstown Sheet & Tube, vowed to resist the steel workers’ union. In response to the opposition, 75,000 workers walked out and violence flared. In May 1937, police in South Chicago opened fire on marchers at the Republic mill, killing ten. Soon after, the strike was routed, but in 1941 the National Labor Relations Board ordered “Little Steel” to recognize the United Steelworkers of America and to reinstate all workers fired for union activity.

Did the New Deal end the Great Depression?

On July 2, 1932, Franklin D. Roosevelt accepted the Democratic nomination for president and pledged “a new deal for the American people.” He promised public works, agricultural price supports, new mortgage markets, working-hours legislation, securities regulation, freer world trade, reforestation, and repeal of Prohibition. Congress passed all these laws.

But did the New Deal end the Depression?

In 1995, academic economists were asked them if they agreed or disagreed with the following statement: “Taken as a whole, government policies of the New Deal served to lengthen and deepen the Great Depression.” Fifty-one percent disagreed, and 49 percent agreed.

America’s Gross National Product 1928 to 1939:

1928: $100 billion

1933: $55 billion

1939: $85 billion

Amount of consumer goods brought 1928 to 1939:

1928: $80 billion

1933: $45 billion

1939: $65 billion

Private investment in industry:

1928: $15 billion

1933: $2 billion

1939: $10 billion

Number unemployed in America:

1929: $2.6 million

1933: $15 million

1935: $11 million

1937: $8.3 million

1938: $10.5 million

1939: $9.2 million