The New Deal

The First 100 Days

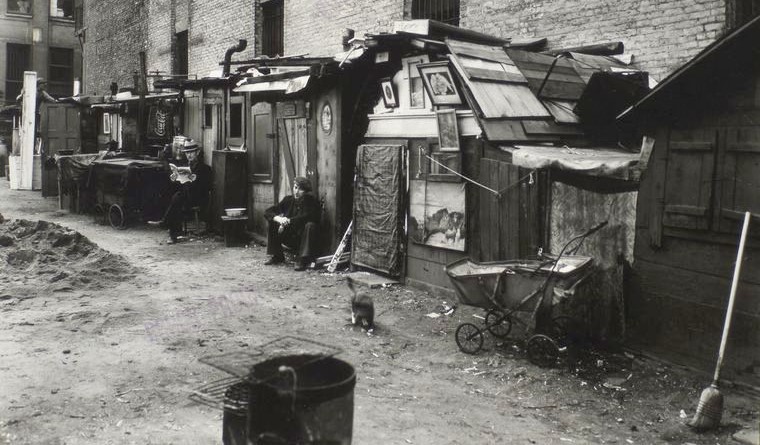

The nation’s plight on March 4, 1933, the day Franklin Roosevelt assumed the presidency, was desperate. A quarter of the nation’s workforce was jobless. A quarter million families had defaulted on their mortgages the previous year. During the winter of 1932 and 1933, some 1.2 million Americans were homeless. Scores of shantytowns (called Hoovervilles) sprouted up.

Since 1929, about 9,000 banks, holding the savings of 27 million families, had failed. Of those bank failings, 1,456 folded in 1932 alone. Farm foreclosures were averaging 20,000 a month. The public was desperate for action. Hamilton Fish, a conservative Republican congressman, promised the president that Congress would “give you any power that you need.”

A month before taking office, Giuseppe Zangara, a mentally ill bricklayer, tried to assassinate the president-elect in Miami. Chicago’s mayor was killed, but Roosevelt miraculously escaped injury. In his inaugural address, Roosevelt expressed confidence that his administration could end the Depression. “The only thing we have to fear,” he declared, “is fear itself.”

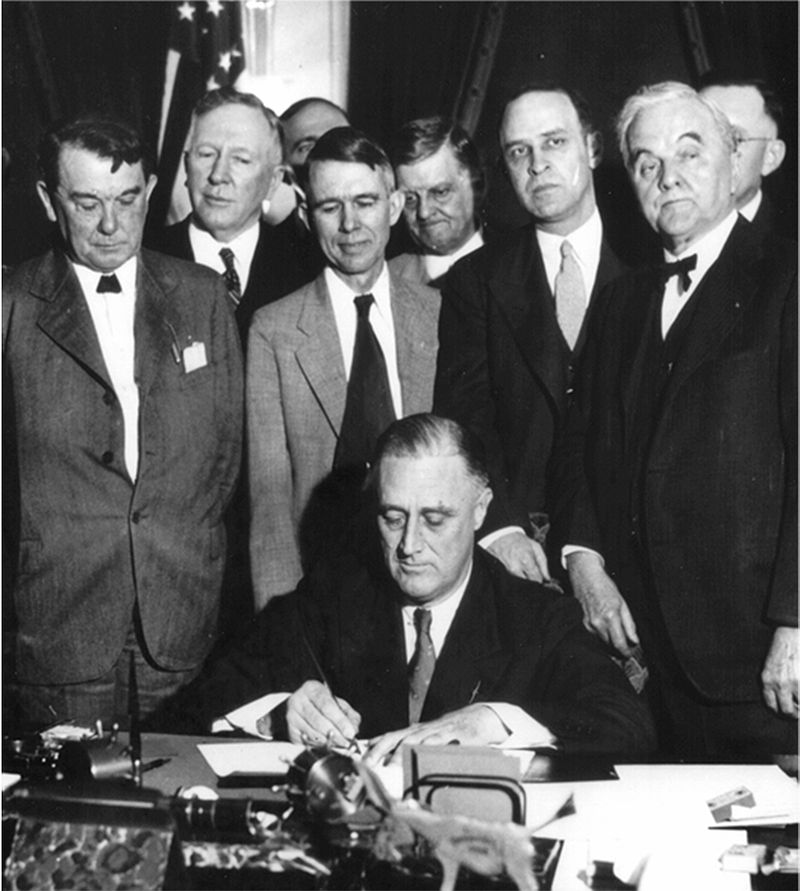

In Roosevelt’s first hundred days in office, he pushed fifteen major bills through Congress. The bills would reshape every aspect of the economy, from banking and industry to agriculture and social welfare. The president promised decisive action. He called Congress into special session and demanded “broad executive power to wage a war against the emergency, as great as the power that would be given me if we were in fact invaded by a foreign foe.”

Roosevelt attacked the bank crisis first. He declared a national bank holiday, which closed all banks. In just four days, his aides drafted the Emergency Banking Relief Act, which permitted solvent banks to reopen under government supervision, and allowed the RFC to buy the stock of troubled banks and to keep them open until they could be reorganized. The law also gave the president broad powers over the Federal Reserve System. The law radically reshaped the nation’s banking system. Congress passed the law in just eight hours.

Roosevelt appealed directly to the people to generate support for his program. On March 12, he conducted the first of many radio “fireside chats.” Using the radio in the way later presidents exploited television, he explained what he had done in plain, simple terms and told the public to have “confidence and courage.” When the banks reopened the following day, people demonstrated their faith by making more deposits than withdrawals. One of Roosevelt’s key advisors did not exaggerate when he later boasted, “Capitalism was saved in eight days.”

The president quickly pushed ahead on other fronts. The Federal Emergency Relief Act pumped $500 million into state-run welfare programs. The Homeowners Loan Act provided the first federal mortgage financing and loan guarantees. By the end of Roosevelt’s first term, the Homeowners Loan Act provided more than 1 million loans totaling $3 billion. The Glass-Steagall Act provided a federal guarantee of all bank deposits under $5,000, separated commercial and investment banking, and strengthened the Federal Reserve’s ability to stabilize the economy.

In addition, Roosevelt took the nation off the gold standard, devalued the dollar, and ordered the Federal Reserve System to ease credit. Other important laws passed during the 100 days included the Agricultural Adjustment Act—the nation’s first system of agricultural price and production supports; the National Industrial Recovery Act—the first major attempt to plan and regulate the economy — and the Tennessee Valley Authority Act—the first direct government involvement in energy production.

The New Dealers

Franklin Roosevelt brought a new breed of government officials to Washington. Previously, most government administrators were wealthy patricians, businessmen, or political loyalists. Roosevelt, however, looked to new sources of talent, bringing to Washington a team of Ivy League intellectuals and New York State social workers. Known as the “brain trust,” these advisors provided Roosevelt with economic ideas and oratorical ammunition.

The New Dealers were strongly influenced by the Progressive reformers of the early twentieth century, who believed that government had not only a right but a duty to intervene in all aspects of economic life in order to improve the quality of American life. In one significant respect, however, the New Dealers differed decisively from the Progressives. Progressive reform had a strong moral dimension. Many reformers wanted to curb drinking, eliminate what they considered immoral sexual behavior, and reshape human character. In comparison, the New Dealers were much more pragmatic—an attitude vividly illustrated by an incident that took place during World War I. One of the most intense policy debates during the war was whether to provide American troops with condoms. The Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels rejected the idea, fearing that it would corrupt the troops’ morals:

“It is wicked to seem to encourage and approve placing in the hands of the men an appliance which will lead them to think they may indulge in practices which are not sanctioned by moral…law.”

While Daniels was on vacation, however, Franklin Roosevelt authorized prophylactics for sailors. Pragmatism, not moral reform, would be a key New Deal theme.

Apart from their commitment to pragmatism, the New Dealers were unified in their rejection of laissez-faire orthodoxy—the idea that federal government’s responsibilities were confined to balancing the federal budgets and providing for the nation’s defense. The New Dealers did, however, disagree profoundly about the best way to end the Depression. They offered three alternative prescriptions for rescuing the nation’s economy. The “trust-busters,” led by Thurman Arnold, called for vigorous enforcement of anti-trust laws to break-up concentrated business power. The “associationalists” wanted to encourage cooperation between business, labor, and government by establishing associations and codes supported by the three parties. The “economic planners,” led by Rexford Tugwell, Adolph Berle, and Gardiner Means, wanted to create a system of centralized national planning.

Roosevelt never aligned himself with any of these factions. He summed up his pragmatic attitude: “Take a method and try it,” he said, “if it fails admit it frankly and try another. But above all try something.”

The Farmers’ Plight

Roosevelt moved aggressively to address the crisis facing the nation’s farmers. No group was harder hit by the Depression than farmers and farm workers. At the start of the Depression, a fifth of all American families still lived on farms. These families, however, were in deep trouble. Farm income fell by a staggering two-thirds during the Depression’s first three years. A bushel of wheat that sold for $2.94 in 1920 dropped to $1 in 1929 and 30 cents in 1932. In one day, a quarter of Mississippi’s farm acreage was auctioned off to pay for debts.

The farmers’ problem, ironically, was that they grew too much. Worldwide crop production soared—a result of more efficient farm machinery, stronger fertilizers, and improved plant varieties—but demand fell. People ate less bread, Europeans imposed protective tariffs, and consumers replaced cotton with rayon. Too much was being grown, and the glut caused prices to fall. In order to meet farm debts in 1932, farmers needed to grow 2.5 times as much corn as they grew in 1929, 2.7 times as much wheat, and 2.4 times as much cotton.

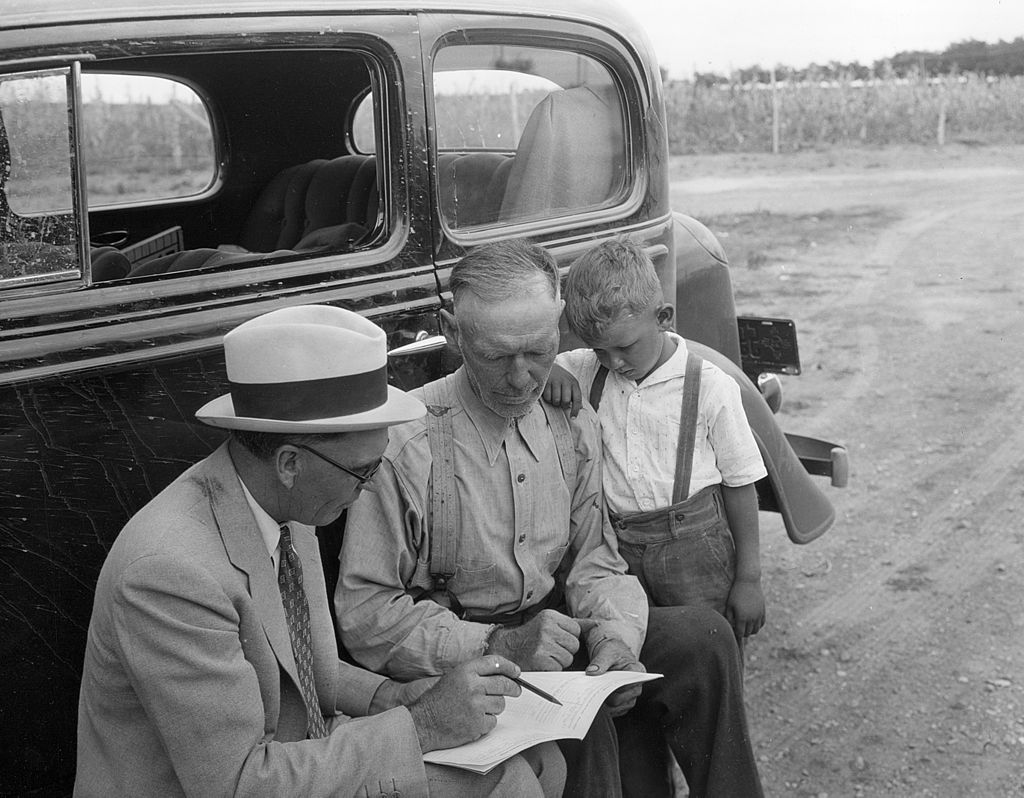

As farm incomes fell, farm tenancy soared. Two-fifths of all farmers worked on land that they did not own. The Gudgers, a white southern Alabama sharecropping family of six, illustrated the plight of tenants who were slipping deeper and deeper into debt. Each year, their landlord provided them with twenty acres of land, seed, an unpainted one-room house, a shed, a mule, fertilizer, and ten dollars a month. In return, they owed him half of their corn and cotton crop and eight percent interest on their debts. In 1934, they were eighty dollars in debt. By 1935, their debts had risen another twelve dollars.

Nature itself seemed to have turned against farmers. In the South, the boll weevil devoured the cotton crop. On the Great Plains, the top soil literally blew away, piling up in ditches like “snow drifts in winter.” The Dust Bowl produced unparalleled human tragedy, but it had not occurred by accident. The Plains had always been a harsh, arid inhospitable environment. Nevertheless, a covering of tough grass-roots, called sod, permitted the land to retain moisture and support vegetation. During the 1890s, however, overgrazing by cattle severely damaged the sod. Then, during World War I, demand for wheat and the use of gasoline-powered tractors allowed farmers to plow large sections of the prairie for the first time. The fragile skin protecting the prairie was destroyed. When drought struck, beginning in 1930, and temperatures soared (to 108 degrees in Kansas for weeks on end) the wind began to blow the soil away. One Kansas county, which produced 3.4 million bushels of wheat in 1931, harvested just 89,000 bushels in 1933.

Tenant farmers found themselves evicted from their land. By 1939, a million Dust Bowl refugees and other tenant farmers left the Plains to work as itinerant produce pickers in California. As a result, whole counties were depopulated. In one part of Colorado, 2,811 homes were abandoned, while an additional 1,522 people simply disappeared.

The New Deal attacked farm problems through a variety of programs. Rural electrification programs meant that for the first time Americans in Appalachia, the Texas Hill Country, and other areas would have the opportunity to share in the benefits of electricity and running water. As late as 1935, more than 6 million of America’s 6.8 million farms had no electricity. Unlike their sisters in the city, farm women had no washing machines, refrigerators, or vacuum cleaners. Nor did private utility companies intend to change things. Private companies insisted that it would be cost prohibitive to provide electrical service to rural areas.

Roosevelt disagreed. Settling on the 40,000 square mile valley of the Tennessee River as his test site, Roosevelt decided to put the government into the electric business. Two months after he took office, Congress passed a bill creating the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). The TVA was authorized to build 21 dams to generate electricity for tens of thousands of farm families. In 1935, Roosevelt signed an executive order creating the Rural Electrification Administration (REA) to bring electricity generated by government dams to America’s hinterland. Between 1935 and 1942, the lights came on for 35 percent of America’s farm families.

Electricity was not the only benefit the New Deal bestowed on farmers. The Soil Conservation Service helped farmers battle erosion. The Farm Credit Administration provided some relief from farm foreclosures. The Commodity Credit Corporation permitted farmers to use stored products as collateral for loans. Roosevelt’s most ambitious farm program, however, was the Agriculture Adjustment Act (AAA).

The AAA, led by Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace, sought a partnership between the government and major producers. Together the new allies would raise prices by reducing the supply of farm goods. Under the AAA, the large producers, acting through farm cooperatives, would agree upon a “domestic allotment” plan that would assign acreage quotas to each producer. Participation would be voluntary. Farmers who cut production to comply with the quotas would be paid for land left fallow.

Unfortunately for its backers, the AAA got off to a horrible start. Because the 1933 crops had already been planted by the time Congress established the AAA, the administration ordered farmers to plow their crops under. The government paid them over $100 million to plow under ten million acres of cotton. The government also purchased and slaughtered six million pigs, salvaging only one million pounds of meat for the needy. The public neither understood nor forgave the agency for destroying food while jobless people went hungry.

Overall, the Agricultural Adjustment Act’s record was mixed. It raised farm income, but did little for sharecroppers and tenant farmers—the groups hardest hit by the agricultural crisis. Farm incomes doubled between 1933 and 1936, but large farmers reaped most of the benefits. Many large landowners used government payments to purchase tractors and combines, allowing them to mechanize farm operations, increase crop yields and reduce the need for sharecroppers and tenants. One Mississippi planter bought 22 tractors with his payments and, subsequently, evicted 160 tenant families. The New Deal farm policies unintentionally forced at least three million small farmers from the land. For all its inadequacies, however, the AAA established the precedence for a system of farm price supports, subsidies, and surplus purchases that still continues more than 75 years later.

The National Recovery Administration

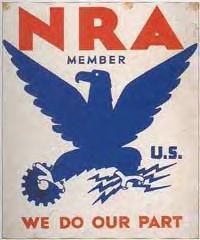

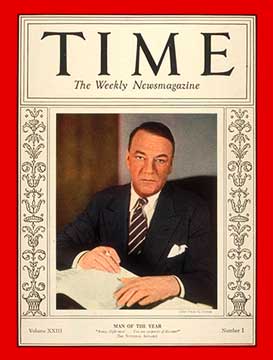

Congress established the National Recovery Administration (NRA) to help revive industry and labor through rational planning. The idea behind the NRA was simple: representatives of business, labor, and government would establish codes of fair practices that would set prices, production levels, minimum wages, and maximum hours within each industry. The NRA also supported workers’ right to join labor unions. The NRA sought to stabilize the economy by ending ruinous competition, overproduction, labor conflicts, and deflating prices.

Led by General Hugh Johnson, the new agency got off to a promising start. By midsummer 1933, over 500 industries had signed codes covering 22 million workers. In New York City, burlesque show strippers agreed on a code limiting the number of times that they would undress each day. By the end of the summer, the nation’s ten largest industries had been won over, as well as hundreds of smaller businesses. All across the land businesses displayed the “Blue Eagle,” the insignia of the NRA, in their windows. Thousands participated in public rallies and spectacular torchlight parades.

The NRA’s success was short-lived. Johnson proved to be an overzealous leader who alienated many business people. Instead of creating a smooth-running system, Johnson presided over a chorus of endless squabbling. The NRA boards, which were dominated by representatives of big business, drafted codes that favored their interests over those of small competitors. Moreover, even though they controlled the new agency from the outset, many leaders of big business resented the NRA for interfering in the private sector. Many quipped that the NRA stood for “national run-around.”

For labor, the NRA was a mixed blessing. On the positive side, the codes abolished child labor and established the precedent of federal regulation of minimum wages and maximum hours. In addition, the NRA boosted the labor movement by drawing large numbers of unskilled workers into unions. On the negative side, however, the NRA codes set wages in most industries well below what labor demanded, and large occupational groups, such as farm workers, fell outside the codes’ coverage.

Jobs Programs

Harry Hopkins, one of Roosevelt’s most trusted advisors, asked why the federal government could not simply hire the unemployed and put them to work. Reluctantly, Roosevelt agreed.

The first major program to attack unemployment through public works was the Public Works Administration (PWA). It was supposed to serve as a “pump-primer,” providing people with money to spend on industrial products. In six years the PWA spent $6 billion, building such projects as the port in Brownsville, Texas, the Grand Coulee Dam, and a sewer system in Chicago. Unfortunately, the man who headed the program, Harold Ickes, was so concerned about potential graft and scandal that the PWA did not spend sufficient money to significantly reduce unemployment.

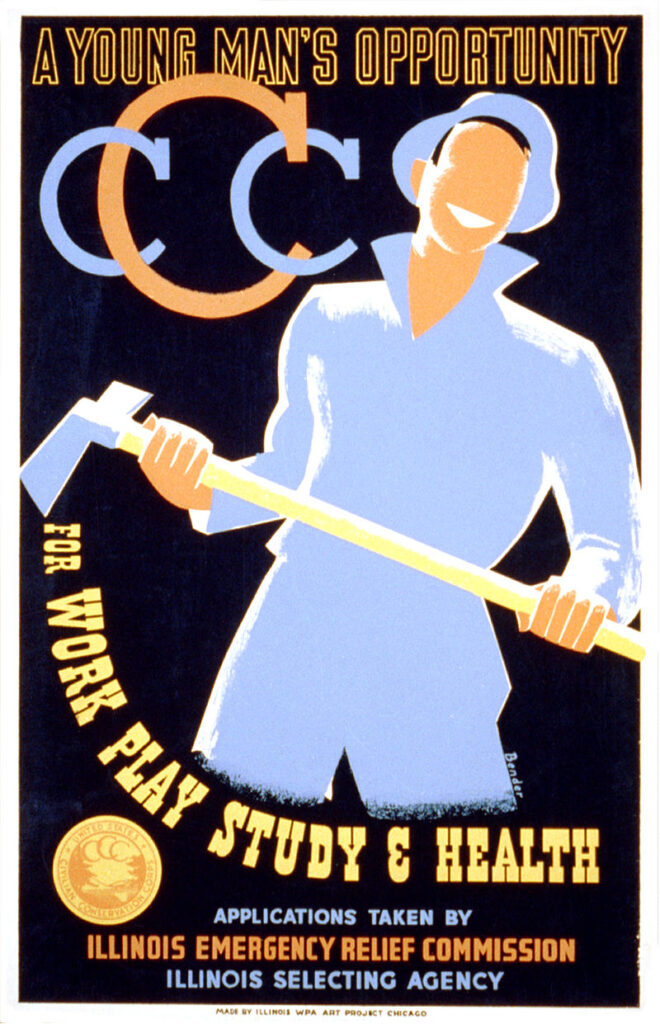

One of the New Deal’s most famous jobs programs was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). By mid-1933, some 300,000 jobless young men between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five were hired to work in the nation’s parks and forests. For $30 a month, CCC workers planted saplings, built fire towers, restocked depleted streams, and restored historic battlefields. Workers lived in wilderness camps, earning money that they passed along to their families. By 1942, when the program ended, 2.5 million men had served in Roosevelt’s “Tree Army.” Despite its immense popularity, the CCC failed to make a serious dent in Depression unemployment. It excluded women, imposed rigid quotas on blacks, and offered employment to only a minuscule number of the young people who needed work.

Far more ambitious was the Civil Works Administration (CWA), established in November 1933. Under the energetic leadership of Harry Hopkins, the CWA put 2.6 million men to work in its first month. Within two months it employed 4 million men building 250,000 miles of road, 40,000 schools, 150,000 privies, and 3,700 playgrounds. In March 1934, however, Roosevelt scrapped the CWA because he (like Hoover) did not want to run a budget deficit or to create a permanent dependent class.

Roosevelt badly underestimated the severity of the crisis. As government funding slowed down and economic indicators leveled off, the Depression deepened in 1934. Intense despair triggered a series of violent strikes, which culminated on Labor Day 1934, when 500,000 garment workers launched the single largest strike in the nation’s history. All across the land, critics attacked Roosevelt for not doing enough to combat the Depression. These charges did not go unheeded in the White House.

Following the congressional elections of 1934, in which the Democrats won thirteen new House seats and nine new Senate seats, Roosevelt abandoned his hopes for a balanced budget. He decided that bolder action was required. He had lost faith in government planning and the proposed alliance with business, which left only one other road to recovery—government spending. Encouraged by the CCC’s success, he decided to create more federal jobs for the unemployed.

In January 1935, Congress created the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Roosevelt’s program employed 3.5 million workers at a “security wage”—twice the level of welfare payments, but well below union scales. Roosevelt, again, turned to Harry Hopkins to head the new agency. Since the WPA’s purpose was to employ men quickly, Hopkins opted for labor-intensive tasks, creating jobs that were often makeshift and inefficient. Jeering critics said the WPA stood for “We Piddle Along,” but the agency built many worthwhile projects. In its first five years alone, the WPA constructed or improved 2,500 hospitals, 5,900 schools, 1,000 airport fields (including New York’s LaGuardia Airport), and nearly 13,000 playgrounds. By 1941 it had pumped $11 billion into the economy.

The WPA’s most unusual feature was its spending on cultural programs. Roughly five percent of the WPA’s spending went to the arts. While folksingers like Woody Guthrie honored the nation in ballads, other artists were hired to catalog it, photograph it, paint it, record it, and write about it. In photojournalism, for example, the Farm Security Agency (FSA) employed scores of photographers to create a pictorial record of America and its people. WPA alumni include writers Saul Bellow, John Cheever, Ralph Ellison, and Richard Wright, the artist Jackson Pollack, and actor and director Orson Welles.

Under the auspices of the WPA, the Federal Writers Project sponsored an impressive set of state guides and dispatched an army of folklorists into the backcountry in search of tall tales. Oral historians collected slave narratives, and musicologists compiled an amazing collection of folk music. Other WPA programs included the Theatre Project, which produced a running commentary on everyday affairs. The Art Project, which decorated the nation’s libraries and post offices with murals of muscular workmen, bountiful wheat fields, and massive machinery.

Valuable in their own right, the WPA’s cultural programs had the added benefit of providing work for thousands of writers, artists, actors, and other creative people. In addition, these programs established the precedent of federal support to the arts and humanities, laying the groundwork for future federal programs to promote the life of the mind in the United States.

In 1939, a Gallup Poll asked Americans what they liked best and what they liked worst about Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal. The answer to both questions was: “The WPA, the Works Projects Administration.”

Work crews were criticized for spending days moving leaf piles from one side of the street to the other. Unions went on strike to protest the program’s refusal to pay wages equal to those of the private sector. President Ronald Reagan, a staunch critic of large-scale government programs, was one of the WPA’s defenders, however. “Some people,” he said, “have called it boondoggle and everything else. But having lived through that era and seen it, no, it was probably one of the social programs that was most practical in those New Deal days.”

The WPA was not especially efficient. In Washington, D.C., construction costs typically ran three-to-four times the cost of private work. Although, this was intentional. The WPA avoided cost-saving machinery in order to hire more workers. At its peak, the WPA spent $2.2 billion a year, or approximately $30 billion annually in current dollars.