Franklin D. Roosevelt

FDR

In June 1932, Franklin D. Roosevelt received the Democratic presidential nomination. At first glance, he did not look like a man who could relate to other peoples’ suffering—Roosevelt had spent his entire life in the lap of luxury. No fewer than sixteen of his ancestors had come over on the Mayflower. A fifth cousin of Teddy Roosevelt, he was born in 1882 to one of New York’s wealthiest families.

Roosevelt enjoyed a privileged youth. He attended Groton, an exclusive private school, and then went to Harvard University and Columbia Law School.

After three years in the New York state senate, Roosevelt was tapped by President Wilson to serve as Assistant Secretary of the Navy in 1913.

His status as the rising star of the Democratic Party was confirmed when James Cox chose Roosevelt as his running mate in the presidential election of 1920.

The Election of 1932

Handsome and outgoing, Roosevelt seemed to have a bright political future. Then disaster struck. In 1921, he was stricken with polio. The disease left him paralyzed from the waist down and confined to a wheelchair for the rest of his life. Instead of retiring, however, Roosevelt labored diligently to return to public life. “If you had spent two years in bed trying to wiggle your toe,” he later declared, “after that anything would seem easy.”

Buoyed by an exuberant optimism and devoted political allies, Roosevelt won the governorship of New York in 1928—one of the few Democrats to survive the Republican landslide. Surrounding himself with able advisors, Roosevelt labored to convert New York into a laboratory for reform, involving conservation, old-age pensions, public works projects, and unemployment insurance.

In his acceptance speech before the Democratic convention in Chicago, Roosevelt promised “a New Deal for the American people.” Although his speech contained few concrete proposals, Roosevelt radiated confidence, giving many desperate voters hope. He even managed during the campaign to turn his lack of a blueprint into an asset, offering instead a policy of experimentation. “It is common sense to take a method and try it,” he declared, “if it fails, admit it frankly and try another.”

The Bonus Army

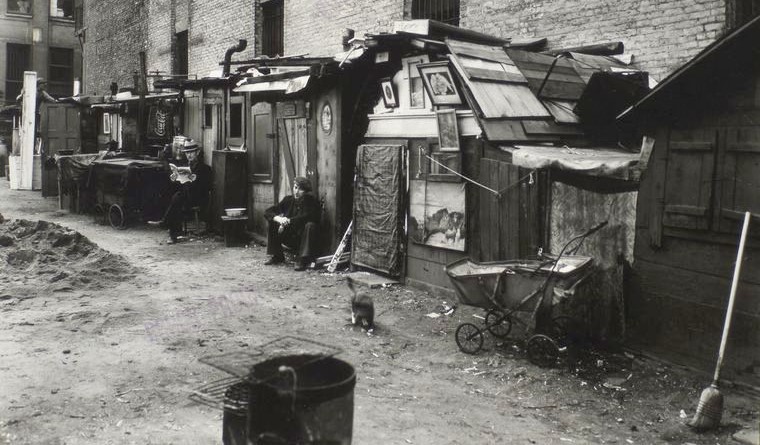

The Bonus Army incident that took place in the summer of 1932 virtually assured Roosevelt’s election. By then, the unemployment rate had reached 23.6 percent. Over twelve million were jobless (out of a labor force of 51 million).

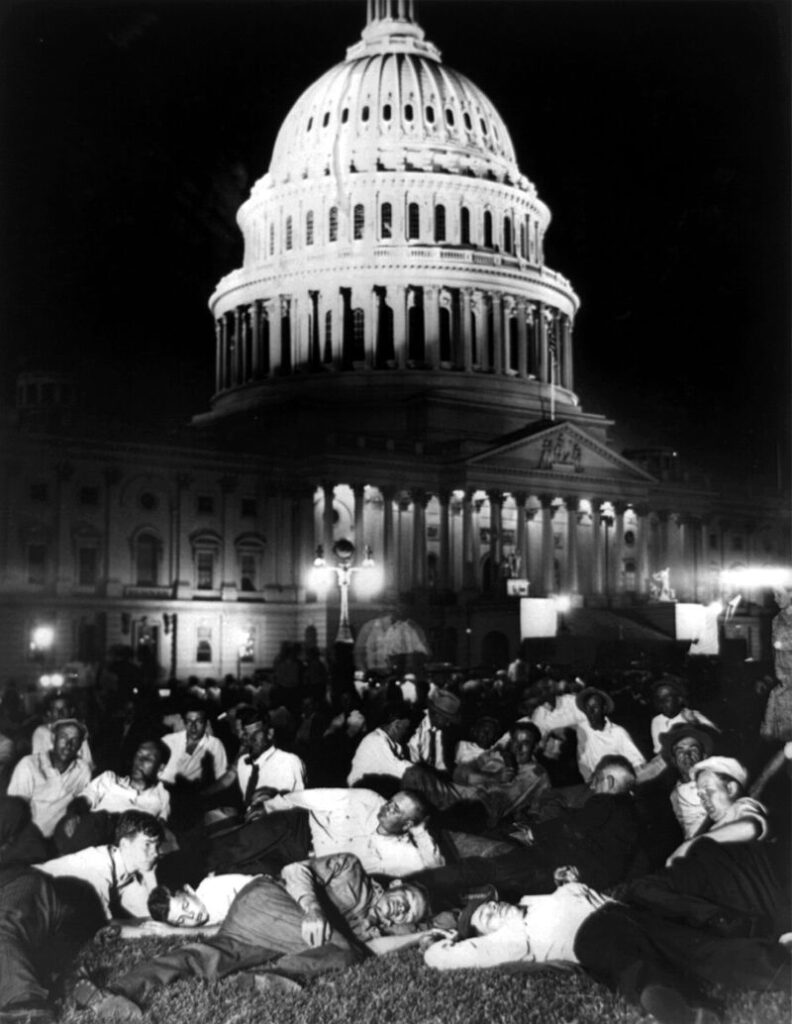

Some 20,000 World War I veterans and their families marched on Washington. Their purpose was to pressure Congress into voting for immediate payment of a veteran’s bonus earmarked for 1945. The proposal was to pay veterans $1 for each day served in the United States and $1.25 for every day overseas. The Democratic-controlled House approved the measure, but the Republican Senate refused. Meanwhile, thousands of veterans jammed the Capitol grounds.

On June 7, as 100,000 watched, some 8,000 veterans marched down Pennsylvania Avenue. By mid-July, the White House was “guarded from veterans” by “the greatest massing of policemen seen in Washington since the race riot after the World War.”

District of Columbia officials, under White House pressure, ordered the Bonus Army’s camps evacuated. A skirmish turned into a riot; two police officers and two veterans were killed. President Hoover called on the Army to “put an end to rioting and defiance of authority.”

The Third Cavalry advanced on the veterans, followed by infantry with fixed bayonets, a machine gun detachment, troops with tear gas canisters, and six midget tanks. The camps were burned. The flames and smoke from the torched shack burned near the Capitol dome. Chief of Staff Douglas MacArthur claimed the “mob” had been “animated by the essence of revolution.”

Although Hoover was appalled by what happened, he publicly accepted the responsibility and endorsed MacArthur’s charge that the bonus marchers included dangerous radicals who wanted to overthrow the government.

Most Americans felt outraged by the government’s harsh treatment of the Bonus Army, and Hoover encountered resentment everywhere he campaigned.

Upon learning of the Bonus Army incident, Franklin D. Roosevelt remarked: “Well, this will elect me.” Roosevelt was correct.

He buried Hoover in November, winning 22,809,638 votes to Hoover’s 15,758,901 votes, and 472 to 59 electoral votes. In addition, the Democrats won commanding majorities in both houses of Congress.