The Toll of the Great Depression

Thinking Comparatively

The Great Depression in Global Perspective

The Great Depression was a global phenomenon, unlike previous economic downturns which generally were confined to a handful of nations or specific regions. Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, and North and South America all suffered from the economic collapse. International trade fell thirty percent as nations tried to protect their industries by raising tariffs on imported goods. “Beggar-thy-neighbor” trade policies were a major reason why the Depression persisted as long as it did. By 1932, an estimated thirty million people were unemployed around the world.

Also, in contrast to the relatively brief economic “panics” of the past, the Great Depression dragged on with no end in sight. As the Depression deepened, it had far-reaching political consequences. One response to the Depression was military dictatorship—a response that could be found in Argentina and in many countries in Central America. Western industrialized countries cut back sharply on the purchase of raw materials and other commodities. The price of coffee, cotton, rubber, tin, and other commodities dropped forty percent. The collapse in raw material and agricultural commodity prices led to social unrest, resulting in the rise of military dictatorships that promised to maintain order.

A second response to the Depression was fascism and militarism—a response found in Germany, Italy, and Japan. In Germany, Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party promised to restore the country’s economy and to rebuild its military. After becoming chancellor in 1932, Hitler outlawed labor unions, restructured German industry into a series of cartels, and after 1935, instituted a massive program of military rearmament that ended high unemployment. In Italy, fascism arose even before the Depression’s onset under the leadership of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini. In Japan, militarists seized control of the government during the 1930s. In an effort to relieve the Depression, Japanese military officers conquered Manchuria, a region rich in raw materials, and coastal China in 1937.

A third response to the Depression was totalitarian Communism. In the Soviet Union, the Great Depression helped solidify Joseph Stalin’s grip on power. In 1928, Stalin instituted a planned economy. His First Five Year Plan called for rapid industrialization and “collectivization” of small peasant farms under government control. To crush opposition to his program, which required peasant farmers to give their products to the government at low prices, Stalin exiled millions of peasants to labor camps in Siberia and instituted a program of terror called the Great Purge. Historians estimate that as many as ten million Soviets died during the 1930s as a result of famine and deliberate killings.

A final response to the Depression was welfare capitalism, which could be found in countries including Canada, Great Britain, and France. Under welfare capitalism, government assumed ultimate responsibility for promoting a reasonably fair distribution of wealth and power and for providing security against the risks of bankruptcy, unemployment, and destitution.

Compared to other industrialized countries, the economic decline brought on by the Depression was steeper and more protracted in the United States. The unemployment rate rose higher and remained higher longer than in any other western society. European countries significantly reduced unemployment by 1936. However, the American jobless rate still exceeded seventeen percent as late as 1939, when World War II began in Europe. It did not drop below fourteen percent until 1941.

The Great Depression transformed the American political and economic landscape. It produced a major political realignment, creating a coalition of big city ethnics, African Americans and Southern Democrats committed, to varying degrees, to interventionist government. The Depression strengthened the federal presence in American life, producing such innovations as national old age pensions, unemployment compensation, aid to dependent children, public housing, federally subsidized school lunches, insured bank deposits, the minimum wage, and stock market regulation. It fundamentally altered labor relations, producing a revived labor movement and a national labor policy protective of collective bargaining. It transformed the farm economy by introducing federal price supports and rural electrification. Above all, the Great Depression produced a fundamental transformation in public attitudes. It led Americans to view the federal government as the ultimate protector of public well-being.

The Human Toll

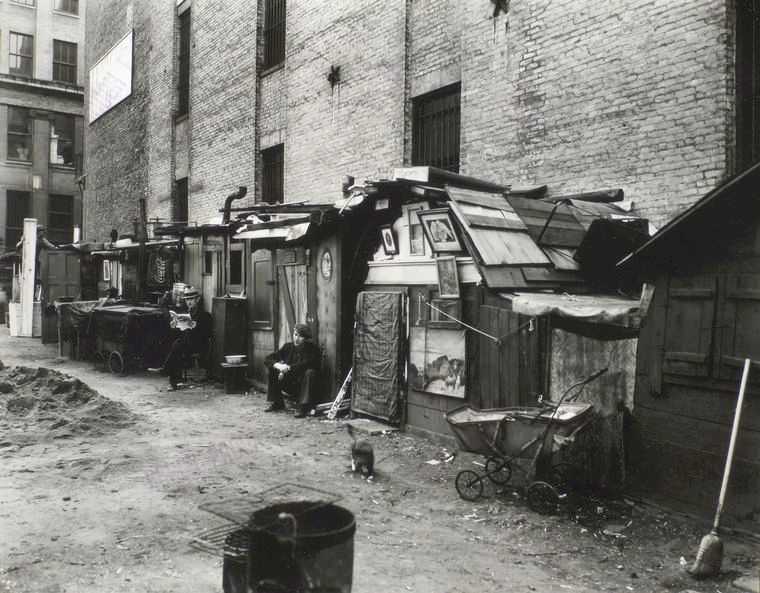

After more than half a century, images of the Great Depression remain firmly etched in the American psyche: breadlines, soup kitchens, tin-can shanties and tar-paper shacks known as “Hoovervilles,” penniless men and women selling apples on street corners, and gray battalions of Arkies and Okies packed into Model A Fords heading to California.

The collapse was staggering in its dimensions. Unemployment jumped from less than 3 million in 1929 to 4 million in 1930, to 8 million in 1931, and to 12.5 million in 1932. In that year, a quarter of the nation’s families did not have a single employed wage earner. Even those fortunate enough to have jobs suffered drastic pay cuts and reductions in working hours. Only one company in ten failed to cut pay, and in 1932, three-quarters of all workers were on part-time schedules, averaging just sixty percent of the normal work week.

The economic collapse was terrifying in its scope and impact. By 1933, average family income had tumbled forty percent, from $2,300 in 1929 to just $1,500 four years later. In the Pennsylvania coal fields, three or four families crowded together in one-room shacks and lived on wild weeds. In Arkansas, families were found inhabiting caves. In Oakland, California, whole families lived in sewer pipes.

Vagrancy shot up as many families were evicted from their homes for nonpayment of rent. The Southern Pacific Railroad boasted that it threw 683,000 vagrants off its trains in 1931. Free public flophouses and missions in Los Angeles provided beds for 200,000 of the uprooted.

To save money, families neglected medical and dental care. Many families sought to cope by planting gardens, canning food, buying used bread, and using cardboard and cotton for shoe soles. Despite a steep decline in food prices, many families did without milk or meat. In New York City, milk consumption declined by a million gallons a day.

President Herbert Hoover declared, “Nobody is actually starving. The hoboes are better fed than they have ever been.” But in New York City in 1931, there were twenty known cases of starvation. In 1934, there were 110 deaths caused by hunger. There were so many accounts of people starving in New York that the West African nation of Cameroon sent $3.77 in relief.

The Depression had a powerful impact on families. It forced couples to delay marriage and drove the birthrate below the replacement level for the first time in American history. The divorce rate fell, for the simple fact that many couples could not afford to maintain separate households or to pay legal fees. Still, rates of desertion soared. By 1940, there were 1.5 million married women living apart from their husbands. More than 200,000 vagrant children wandered the country as a result of the break-up of their families.

The Depression inflicted a heavy psychological toll on jobless men. With no wages to punctuate their authority, many men lost power as primary decision makers. Large numbers of men lost self-respect, became immobilized and stopped looking for work, while others turned to alcohol or became self-destructive or abusive toward their families.

In contrast to men, many women saw their status rise during the Depression. To supplement the family income, married women entered the work force in large numbers. Although most women worked in menial occupations, the fact that they were employed and bringing home paychecks elevated their position within the family and gave them a greater say in family decisions.

Despite the hardships it inflicted, the Great Depression drew some families closer together. As one observer noted: “Many a family has lost its automobile and found its soul.” Families had to devise strategies for getting through hard times because their survival depended on it. They pooled their incomes, moved in with relatives in order to cut expenses, bought day-old bread, and did without. Many families drew comfort from their religion, sustained by the hope things would turn out well in the end. Others placed their faith in themselves, and their own dogged determination to survive. Many Americans, however, no longer believed that the problems could be solved by people acting alone or through voluntary associations. Increasingly, they looked to the federal government for help.

The Dispossessed

Economic hardship and loss visited all sections of the country during the Depression. One-third of the Harvard class of 1911 confessed that they were hard-up, on relief, or dependent on relatives. Doctors and lawyers saw their incomes fall forty percent. No groups suffered more from the Depression than African Americans and Mexican Americans.

A year after the stock market crash, seventy percent of Charleston’s black population was unemployed and seventy-five percent of Memphis’s black population was unemployed. In Macon County, Alabama—home of Booker T. Washington’s famous Tuskegee Institute—most black families lived in homes without wooden floors or windows or sewage disposal and subsisted on salt pork, hominy grits, corn bread, and molasses. Income averaged less than a dollar a day.

Conditions were also distressed in the North. In Chicago, seventy percent of all black families earned less than a $1,000 a year, far below the poverty line. In Chicago and other large northern cities, most African Americans lived in “kitchenettes.” Apartment owners took six-room apartments, which previously rented for $50 a month, and divided them into six smaller-unit kitchenettes. The kitchenettes then rented for $32 dollars a month, assuring landlords a windfall of an extra $142 a month. Buildings that previously held sixty families now contained 300.

The Depression hit Mexican American families especially hard. Mexican Americans faced serious opposition from organized labor, which resented competition from Mexican workers as unemployment rose. Bowing to union pressure, federal, state and local authorities “repatriated” more than 400,000 people of Mexican descent to prevent them from applying for relief. Since this group included many United States citizens, the deportations constituted a gross violation of civil liberties.

Private and Public Charity

The economic crisis of the 1930s overwhelmed private charities and local governments. In South Texas, the Salvation Army provided a penny per person each day. In Philadelphia, private and public charities distributed $1 million a month in poor relief. This amount, however, provided families with only $1.50 a week for groceries. In 1932, total public and private relief expenditures amounted to $317 million—$26 for each of the nation’s 12.5 million jobless.