The Stock Market Crashes

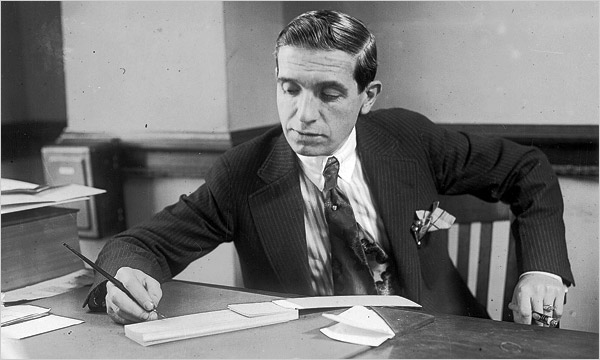

Charles Ponzi

Few people ever see their name enter the English language, but Charles Ponzi did. A “Ponzi scheme” has become synonymous with wild speculation. In September 1919, Ponzi was a 42-year-old former vegetable dealer with just $150 to his name. He promised to return fifteen dollars to anyone who lent him ten dollars for ninety days. His plan, he explained, was to buy foreign currencies at low prices and to sell them at higher prices. After newspapers reported his scheme, dollars began to pour in—one million dollars a week. An admirer described him as the greatest Italian of all time: “Columbus discovered America…but you discovered money.”

The scheme was too good to be true. Ponzi took in fifteen million dollars in eight months, and less than $200,000 was ever returned to investors.

Speculative Manias

Ponzi symbolized the “get-rich-quick” mentality that infected the public during the 1920s. A vivid example was the Florida land boom. During the 1920s, sun worshipping Northerners discovered Florida’s warm winter climate and its sun drenched beaches. Could there be a safer investment? Real estate promoters, including the former presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan, offered seafront lots to investors for ten percent down. Investors snapped up the properties, much of which turned out to be swamp and scrub land. Prices skyrocketed. A lot forty miles from Miami sold for $20,000. A beach lot sold for $75,000. Ponzi himself sold lots “near Jacksonville,” which were actually 65 miles west of the city. He divided each acre into 23 lots.

The bubble burst in the fall of 1926. Two hurricanes ripped through Florida, killing more than 400 people. Property valued at $1 billion in 1925 dropped to $143 million in 1928.

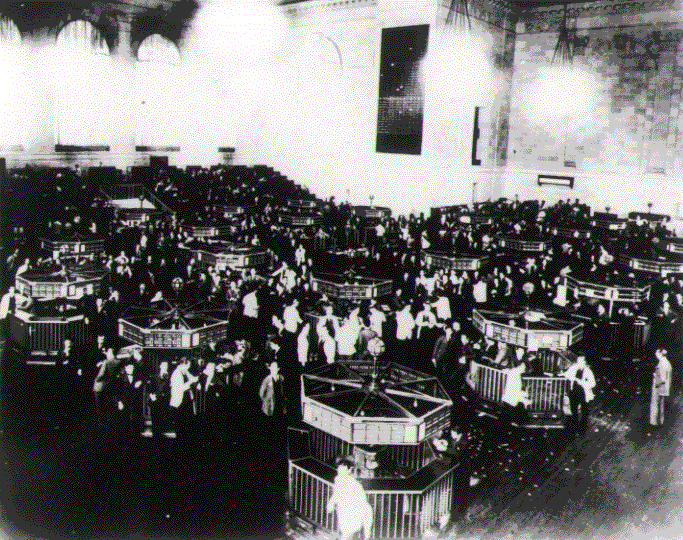

A wave of stock swindles and business frauds took place during the 1920s. But the most striking manifestation of the decade’s speculative frenzy was the stock market booms of 1928 and 1929. After rising steadily during the 1920s, stock prices began to soar in March 1928. Between March 3, 1928, and September 3, 1928, AT&T rose from 179 1/2 to 335 5/8, General Motors from 139 3/4 to 181 7/8, and Westinghouse from 91 5/8 to 313. By the beginning of the fall of 1929, stock prices were four times higher than five years before.

Brokerage houses lured investors into the market by selling stock on margin, requiring investors to only put down ten or twenty percent of the stock’s price in cash and borrowing the rest. By 1929, some 1.5 million Americans had invested in securities.

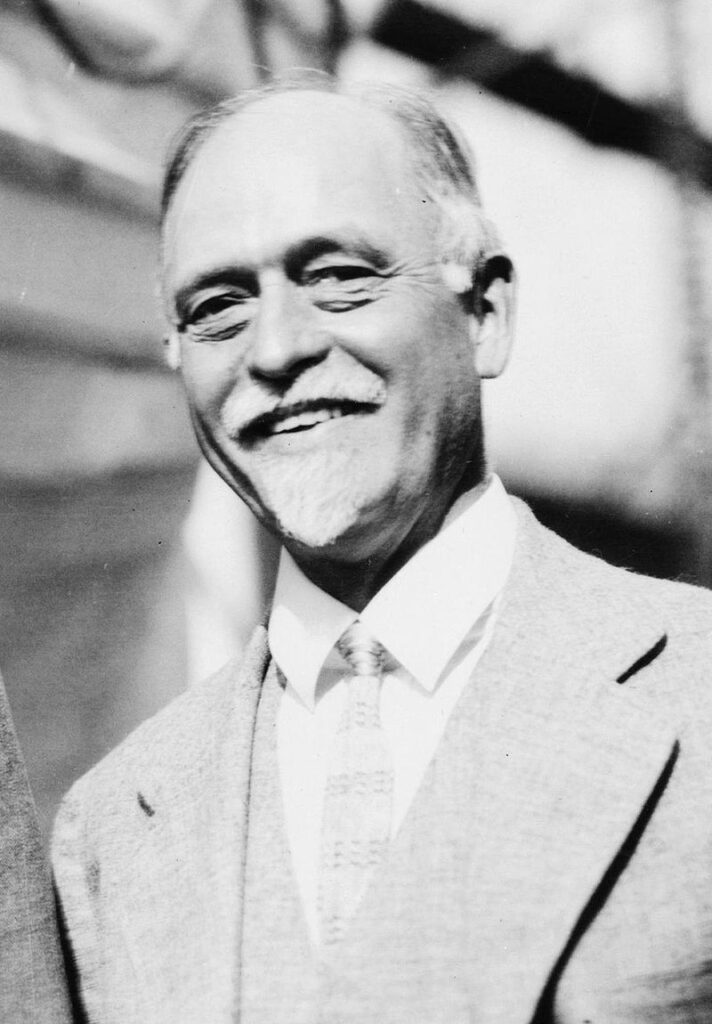

Boosters like John Jacob Raskob, the chairman of the Democratic Party, encouraged ordinary people to invest in stocks. In an article in the Ladies’ Home Journal titled “Everybody Ought to be Rich,” he explained that a person who invested fifteen dollars a month in the stock market for twenty years would have a nest egg of $80,000. Leading economists encouraged investors to believe that the stock market would continue to rise. Irving Fisher of Yale University announced: “Stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau.” At the end of October 1929, the seemingly endless surge in stock prices came to a crashing halt.

The Market Crashes

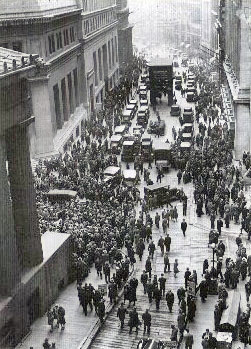

On Thursday, October 24, 1929, an unprecedented wave of sell orders shook the New York Stock Exchange. Stock priced tumbled, falling two, five, and even ten dollars between trades. As prices fell, brokers required investors who had bought stock on margin to put up money to cover their loans. To raise money, many investors dumped stocks for whatever price they could fetch. During the first three hours of trading, stock values plunged by $11 billion.

At noon, a group of prominent bankers met at the offices of J.P. Morgan and Co. to stop the hemorrhaging of stock prices. The bankers’ pool agreed to buy stocks well above the market. At 1:30 p.m., they put their plan into action. Within an hour, U.S. Steel was up $15 a share, AT&T up $22, General Electric up $21, Montgomery Ward up $23.

Even though the market recovered its morning losses, public confidence was badly shaken. Rumors spread that eleven stock speculators had killed themselves and that government troops were surrounding the exchange to protect traders from an angry mob. President Hoover sought to reassure the public by declaring that the “fundamental business of the country…is on a sound and prosperous basis.”

Prices held steady on Friday, and then slipped on Saturday. Monday, however, brought fresh disaster. Eastman Kodak plunged $41 a share, AT&T by $24, New York Central Railroad by $22. But the worst was yet to come. It occurred on Black Tuesday, October 29, the day the stock market experienced the greatest crash in its history.

As soon as the stock exchange’s gong sounded, a mad rush to sell began. Trading volume soared to an unprecedented 16,410,030 shares and the average price of a share fell twelve percent. Stocks were sold for whatever price they would bring. White Sewing Machine had reached a high of $48 a share. One purchaser—reportedly a messenger boy—bought a block of the stock for one dollar a share.

The bull market of the late 1920s was over. By 1932, the index of stock prices had fallen from a 1929 high of 210 to a low of 30. Stocks were valued at just twelve percent of what they had been worth in September 1929. Altogether, between September 1929 and June 1932, the nation’s stock exchanges lost $179 billion in value.

The great stock market crash of October 1929 brought the economic prosperity of the 1920s to a symbolic end. For the next ten years, the United States was mired in a deep economic depression. By 1933, unemployment had soared to 25 percent, up from just 3.2 percent in 1929. Industrial production declined by fifty percent. In 1929 before the crash, investment in the U.S. economy totaled $16 billion. By 1933, the figure had fallen to $340 million—a decrease of 98 percent.

Why It Happened

Why did the seemingly boundless prosperity of the 1920s end so suddenly? And why, once an economic downturn began, did the Great Depression last so long?

Economists have been hard pressed to explain why “prosperity’s decade” ended in financial disaster. In 1929, the American economy appeared to be extraordinarily healthy. Employment was high and inflation was virtually non-existent. Industrial production had risen thirty percent between 1919 and 1929, and per capita income had climbed from $520 to $681. The United States accounted for nearly half of the world’s industrial output. Still, the seeds of the Depression were already present in the “boom” years of the 1920s.

For many groups of Americans, the prosperity of the 1920s was a cruel illusion. Even during the most prosperous years of the Roaring Twenties, most families lived below what contemporaries defined as the poverty line. In 1929, economists considered $2,500 the income necessary to support a family. In that year, more than sixty percent of the nation’s families earned less than $2,000 a year—the income necessary for basic necessities—and over forty percent earned less than $1,500 annually. Although labor productivity soared during the 1920s because of electrification and more efficient management, wages stagnated or fell in mining, transportation, and manufacturing. Hourly wages in coal mines sagged from 84.5 cents in 1923 to just 62.5 cents in 1929.

Prosperity bypassed specific groups of Americans entirely. A 1928 report on the condition of Native Americans found that half earned less than $500 annually and that 71 percent lived on less than $200 a year. Mexican Americans, too, had failed to share in the prosperity. During the 1920s, each year 25,000 Mexicans migrated to the United States. Most lived in conditions of extreme poverty. In Los Angeles the infant mortality rate was five times higher than the rate for Anglos, and most homes lacked toilets. A survey found that a substantial number of Mexican Americans had virtually no meat or fresh vegetables in their diet. Forty percent said that they could not afford to give their children milk.

The farm sector had been mired in depression since 1921. Farm prices had been depressed ever since the end of World War I, when European agriculture revived, and grain from Argentina and Australia entered the world market. Strapped with long-term debts, high taxes, and a sharp drop in crop prices, farmers lost ground throughout the 1920s. In 1910, a farmer’s income was forty percent of a city worker’s. By 1930, it had sagged to just thirty percent.

The decline in farm income reverberated throughout the economy. Rural consumers stopped buying farm implements, tractors, automobiles, furniture, and appliances. Millions of farmers defaulted on their debts, placing tremendous pressure on the banking system. Between 1920 and 1929, more than 5,000 of the country’s 30,000 banks failed.

Because of the banking crisis, thousands of small business people failed because they could not secure loans. Thousands more went bankrupt because they had lost their working capital in the stock market crash. A heavy burden of consumer debt also weakened the economy. Consumers built up an unmanageable amount of consumer installment and mortgage debt, taking out loans to buy cars, appliances, and homes in the suburbs. To repay these loans, consumers cut back sharply on discretionary spending. Drops in consumer spending led inevitably to reductions in production and worker layoffs. Unemployed workers then spent less and the cycle repeated itself.

A poor distribution of income compounded the country’s economic problems. During the 1920s, there was a pronounced shift in wealth and income toward the very rich. Between 1919 and 1929, the share of income received by the wealthiest one percent of Americans rose from twelve percent to nineteen percent, while the share received by the richest five percent jumped from 24 percent to 34 percent. Over the same period, the poorest 93 percent of the non-farm population actually saw its disposable income fall. Because the rich tend to spend a high proportion of their income on luxuries, such as large cars, entertainment, and tourism, and save a disproportionately large share of their income, there was insufficient demand to keep employment and investment at a high level.

Even before the onset of the Depression, business investment had begun to decline. Residential construction boomed between 1924 and 1927, but in 1929 housing starts fell to less than half the 1924 level. A major reason for the depressed housing market was the 1924 immigration law that had restricted foreign immigration.

Soaring inventories also led businesses to reduce investment and production. During the mid-1920s, manufacturers expanded their production capacity and built up excessive inventories. At the decade’s end they cut back sharply, directing their surplus funds into stock market speculation.

The Federal Reserve, the nation’s central bank, played a critical, if inadvertent, role in weakening the economy. In an effort to curb stock market speculation, the Federal Reserve slowed the growth of the money supply, then allowed the money supply to fall dramatically after the stock market crash, producing a wrenching “liquidity crisis.” Consumers found themselves unable to repay loans, while businesses did not have the capital to finance business operations. Instead of actively stimulating the economy by cutting interest rates and expanding the money supply—the way monetary authorities fight recessions today—the Federal Reserve allowed the country’s money supply to decline by 27 percent between 1929 and 1933.

Finally, Republican tariff policies damaged the economy by depressing foreign trade. Anxious to protect American industries from foreign competitors, Congress passed the Fordney-McCumber Tariff of 1922 and the Hawley-Smoot Tariff of 1930, raising tariff rates to unprecedented levels. American tariffs stifled international trade, making it difficult for European nations to pay off their debts. As foreign economies foundered, those countries imposed trade barriers of their own, choking off U.S. exports. By 1933, international trade had plunged thirty percent.

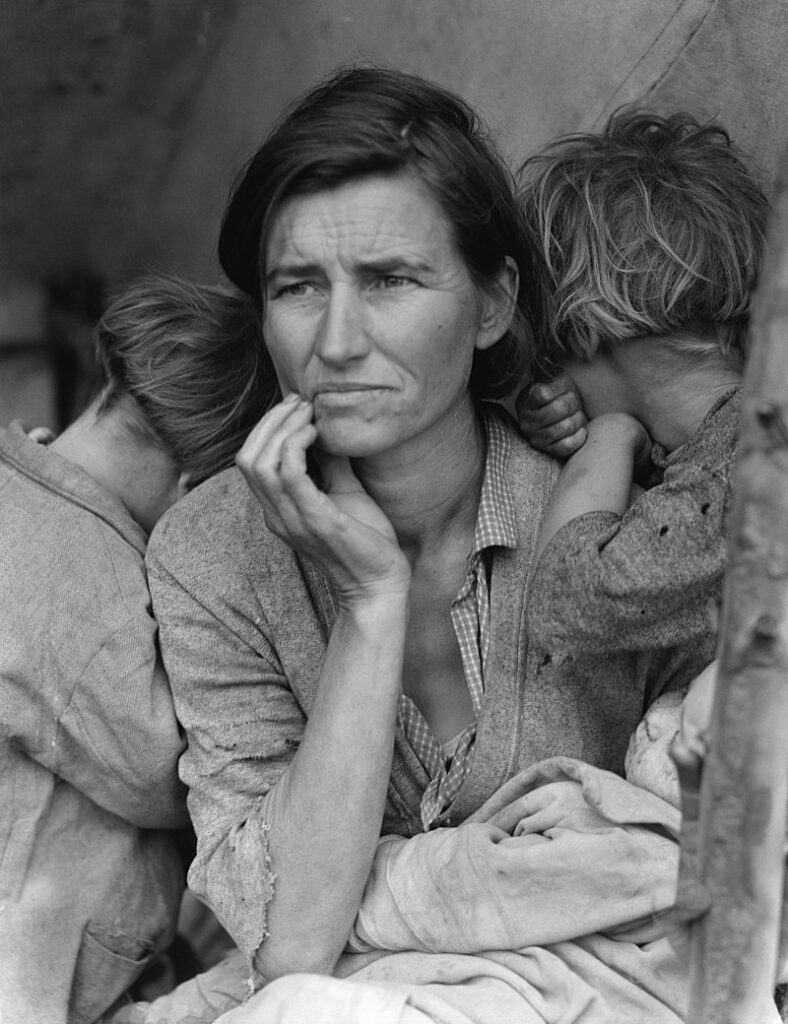

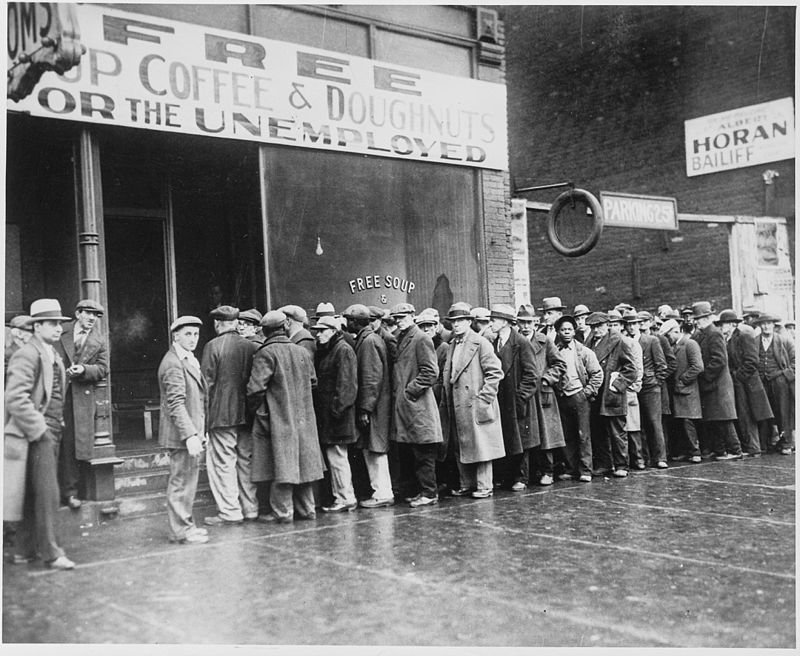

All these factors left the economy ripe for disaster. Yet the depression did not strike instantly. It infected the country gradually, like a slow-growing cancer. Measured in human terms, the Great Depression was the worst economic catastrophe in American history. It hit urban and rural areas, blue-and white-collar families alike. In the nation’s cities, unemployed men took to the streets to sell apples or to shine shoes. Thousands of others hopped freight trains and wandered from town to town looking for jobs or handouts.

Unlike most of Western Europe, the United States had no federal system of unemployment insurance. The relief burden fell on state and municipal governments working in cooperation with private charities, such as the Red Cross and the Community Chest. Created to handle temporary emergencies, these groups lacked the resources to alleviate the massive suffering created by the Great Depression. Poor Southerners, whose states had virtually no relief funds, were particularly hard hit.

Urban centers in the North fared little better. Most city charters did not permit public funds to be spent on work relief. Adding insult to injury, several states disqualified relief clients from voting, while other cities forced them to surrender their automobile license plates. “Prosperity’s decade” had ended in economic disaster.

On October 19, 1987, the U.S. stock market lost almost a quarter of its value—but no depression resulted. On October 27, 1997, the stock market 554.26 points, or 7.18 percent—but again did not lead to a depression. So why then did the stock market crash of 1929 result in a decade-long depression?

Some argue that it was because of troubles in Europe. Germany was unable to pay its debts or its World War I reparations. As a result, Britain and France could not repay their debts to the United States.

Others insist that too much money was invested in overvalued stocks, and when the market began to fall, investors, who had borrowed money to buy stocks, were unable to repay their debts, and banks had to call in loans.

Still others argued that the domestic economy was already in trouble before the stock market crash, but that rising stock prices had obscured such problems as low farm prices, a sharp decline in construction, and overproduction by industry.