The Formation of Modern American Mass Culture

The Formation of Modern American Mass Culture

Many of the defining features of modern American culture emerged during the 1920s. The record chart, the book club, the radio, the talking picture, and spectator sports all became popular forms of mass entertainment. But the 1920s primarily stand out as one of the most important periods in American cultural history because the decade produced a generation of artists, musicians, and writers who were among the most innovative and creative in the country’s history.

Hollywood Versus History

Mass Entertainment

Of all the new appliances to enter the nation’s homes during the 1920s, none had a more revolutionary impact than the radio. Sales of radios soared from $60 million in 1922 to $426 million in 1929. The first commercial radio station began broadcasting in 1919, and during the 1920s, the nation’s airwaves were filled with musical variety shows and comedies.

Radio drew the nation together by bringing news, entertainment, and advertisements to more than ten million households by 1929. Radio blunted regional differences and imposed similar tastes and lifestyles. No other media had the power to create heroes and villains so quickly. When Charles Lindbergh became the first person to fly nonstop across the Atlantic from New York to Paris in 1928, the radio brought this incredible feat into American homes, transforming him into a celebrity overnight.

Radio also disseminated racial and cultural caricatures and derogatory stereotypes. The nation’s most popular radio show, “Amos ‘n Andy,” which first aired in 1926 on Chicago’s WMAQ, spread vicious racial stereotypes into homes whose white occupants knew little about African Americans. Other minorities fared no better. The Italian gangster and the tightfisted Jew became stock characters in radio programming.

The phonograph was not far behind the radio in importance. The 1920s saw the record player enter American life in full force. Piano sales sagged as phonograph production rose from just 190,000 in 1923 to five million in 1929. The popularity of jazz, blues, and “hillbilly” music fueled the phonograph boom. The novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald called the 1920s the “Jazz Age”—and the decade was truly jazz’s golden age. Duke Ellington wrote the first extended jazz compositions. Louis Armstrong popularized “scat” (singing of nonsense syllables). Fletcher Henderson pioneered big band jazz. Trumpeter Jimmy McPartland and clarinetist Benny Goodman popularized the Chicago school of improvisation.

The blues craze erupted in 1920 when a black singer named Mamie Smith released a recording called “Crazy Blues.” The record became a sensation, selling 75,000 copies in a month and a million copies in seven months. Recordings by Ma Rainey, the “Mother of the Blues,” and Bessie Smith, the “Empress of the Blues,” brought the blues, with their poignant and defiant reaction to life’s sorrows, to a vast audience.

“Hillbilly” music broke into mass culture in 1923 when a Georgia singer named “Fiddlin’ John” Carson sold 500,000 copies of his recordings. Another country artist, Vernon Dalhart, sold seven million copies of a recording of “The Wreck of Old 97.” Country music’s appeal was not limited to the rural South or West; city folk, too, listened to country songs, reflecting a deep nostalgia for a simpler past.

The single most significant new instrument of mass entertainment was the movies. Movie attendance soared, from fifty million a week in 1920 to ninety million weekly in 1929. According to one estimate, Americans spent 83 cents of every entertainment dollar going to the movies, and three-fourths of the population went to a movie theater every week.

During the late teens and 1920s, the film industry took on its modern form. In cinema’s earliest days, the film industry was based in the nation’s theatrical center—New York. By the 1920s, the industry had relocated to Hollywood, drawn by its cheap land and labor, the varied scenery that was readily accessible, and a suitable climate ideal for year-round filming. (Some filmmakers moved to avoid lawsuits from individuals like Thomas Edison who owned patent rights over the filmmaking process). Each year, Hollywood released nearly 700 movies, dominating worldwide film production. By 1926, Hollywood had captured 95 of the British market and seventy percent of the French market.

A small group of companies consolidated their control over the film industry and created the “studio system” that would dominate film production for the next thirty years. Paramount, Twentieth Century Fox, MGM, and other studios owned their own production facilities, ran their own worldwide distribution networks, and controlled theater chains committed to showing their companies’ products. In addition, they kept stables of actors, directors, and screenwriters under contract.

The popularity of the movies soared as films increasingly featured glamour, sophistication, and sex appeal. New kinds of movie stars appeared: the mysterious sex goddess, personified by Greta Garbo, the passionate hot-blooded lover, epitomized by Rudolph Valentino, and the flapper, with her bobbed hair and skimpy skirts. New film genres also debuted, including swashbuckling adventures, sophisticated sex comedies, and tales of flaming youth and their new sexual freedom. Americans flocked to see Hollywood spectacles such as Cecil B. DeMille’s Ten Commandments with its “cast of thousands” and dazzling special effects. Comedies, such as the slapstick masterpieces starring Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, enjoyed great popularity as well.

Like radio, movies created a new popular culture with common speech, dress, behavior, and heroes. Like radio, Hollywood did its share to reinforce racial stereotypes by denigrating minority groups. The radio, the electric phonograph, and the silver screen both molded and mirrored mass culture.

Spectator Sports

Spectator sports attracted vast audiences in the 1920s. The country yearned for heroes in an increasingly impersonal, bureaucratic society, and sports provided them.

Prize fighters like Jack Dempsey became national idols. Team sports flourished. However, Americans focused on individual superstars, people whose talents or personalities made them appear larger than life. Knute Rockne and his “Four Horsemen” at Notre Dame spurred interest in college football. Professional football began during the 1920s. In 1925, Harold “Red” Grange, the “Galloping Ghost” halfback for the University of Illinois, attracted 68,000 fans to a professional football game at Brooklyn’s Polo Grounds.

Baseball drew even bigger crowds than football. The decade began, however, with the sport mired in scandal. In 1920, three members of the Chicago White Sox told a grand jury that they and five other players had thrown the 1919 World Series. As a result of the “Black Sox” scandal, eight players were banished from the sport. But baseball soon regained its popularity, thanks to George Herman (“Babe”) Ruth, the sport’s undisputed superstar. Up until the 1920s, Ty Cobb’s defensive brand of baseball, with its emphasis on base hits and stolen bases, had dominated the sport. Ruth transformed baseball into the game of the home-run hitter. In 1921, the New York Yankee slugger hit 59 home runs—more than any other team. In 1927, the “Sultan of Swat” hit sixty home runs.

Hidden History

The Forgotten History of College Sports

Recently, college sports has been on newspapers’ front pages almost as much as it has been on the sports pages. There have been contentious debates about coaches’ salaries, concussions in contact sports, and unionization of college athletes. Controversies rage about whether college athletes are exploited and whether an emphasis on intercollegiate sports diverts attention from universities’ academic responsibilities.

Many of these debates have a long history. In 1893 the president of Harvard argued that athletics had nothing to do with his college’s mission:

With athletics considered as an end in themselves, pursued either for pecuniary profit or popular applause, a college or university has nothing to do. Neither is it an appropriate function for a college or university to provide periodic entertainment during term-time for multitudes of people who are not students.

Nevertheless, college athletics continued to flourish. For well over a century, sports have been a means for colleges to earn money, power, and esteem, sometimes resulting in corruption even as sports attracted applicants to institutions and generated loyalty among alumni and donors.

Today, college sports are a multi-billion-dollar industry. College football coaches generally command higher salaries than university presidents. Local newspapers devote much more attention to college athletics than to any other facet of the college experience.

So when did organized sports become an integral part of college life?

The answer: The middle of the nineteenth century, beginning with rowing, baseball, lacrosse, and football.

Why was it only then that competitive sports were introduced in college?

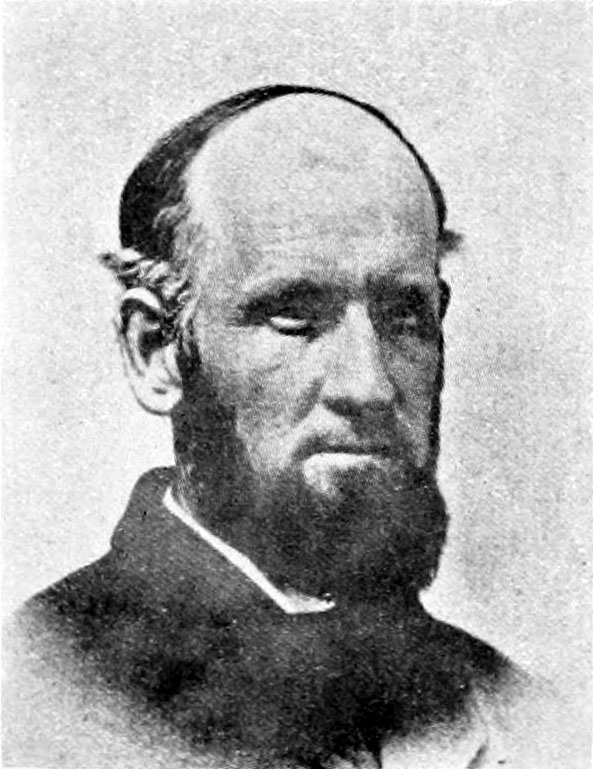

Beginning in the late eighteenth century, student violence ran rampant on many college campuses. Harvard’s first student riot took place in 1766, prompted by an uproar over rotten butter in the dining hall. At many of the early colleges students rioted against bad food, compulsory military drilling, antismoking regulations, and limits on freedom of speech, with students bolting classroom doors, smashing campus windows, and stoning faculty members’ houses. There were six riots at Princeton between 1800 and 1830. During a riot at Harvard, the historian William H. Prescott lost his eyesight. Another riot at Yale resulted in a tutor’s death. During the 1830s, one University of Virginia professor was horse whipped, another stoned, and yet another murdered.

In a bid to restore discipline, colleges resorted to harsh measures, including mass expulsions. Harvard expelled forty-three of seventy members of the class of 1823. Colleges also began to institute grades, which were shared with parents. A far more successful strategy involved colleges gradually broadening their curriculum beyond the classics, introducing expanded offerings in science, as well as the first courses in social science, starting at Oberlin College in 1858 and inaugurating the first electives.

The colleges also started to tolerate a more independent student lifestyle and to permit the establishment of literary societies, fraternities, sporting clubs, and organized athletics. The first fraternity, Kappa Alpha, was formed at Union College in 1825. Organized crew and boat racing were introduced in the 1840s, baseball in the 1850s, and the first intercollegiate football game took place between Rutgers and Princeton in 1869.

A leader in the development of college athletics was Edward Hitchcock, Jr., the son of Amherst College’s president. He was the first professor of hygiene and physical education. In 1861, he began a regiment of daily gymnastics for all students, and encouraged students to play games, including billiards. Hitchcock explained his motivation:

“I urge the necessity of introducing playful exercise, singing college songs, et cetera. Sometimes perhaps this may seem to be boisterous and undignified, but it seems desirable to me that a portion of the animal spirits should be worked off inside the stone walls of the gymnasium under the eye of a college officer rather than out of doors, rendering night hideous.”

His goal was to channel those aggressive impulses of college men, build strong character, and give male students an outlet for their energies. Sports also made students more loyal to their college.

By the 1910s, intercollegiate athletics had already become synonymous with college life in popular culture, evident in books like Owen Johnson’s 1912 best seller, Stover at Yale. Before the 1916 Harvard-Yale game, the Yale coach inspired his players to victory (6-3) when he declared: “Gentlemen, you are now going to play football against Harvard. Never again in your whole life will you do anything so important.”

During the 1920s college football attracted enormous public attention, with sportswriters turning athletes like the University of Illinois’s Red Grange, the Galloping Ghost, and Notre Dames “Four Horsemen,” into nationally known celebrities. College sports acquired symbolic significance, signifying manliness, fortitude, determination, and a true meritocracy where ability won out over all else.

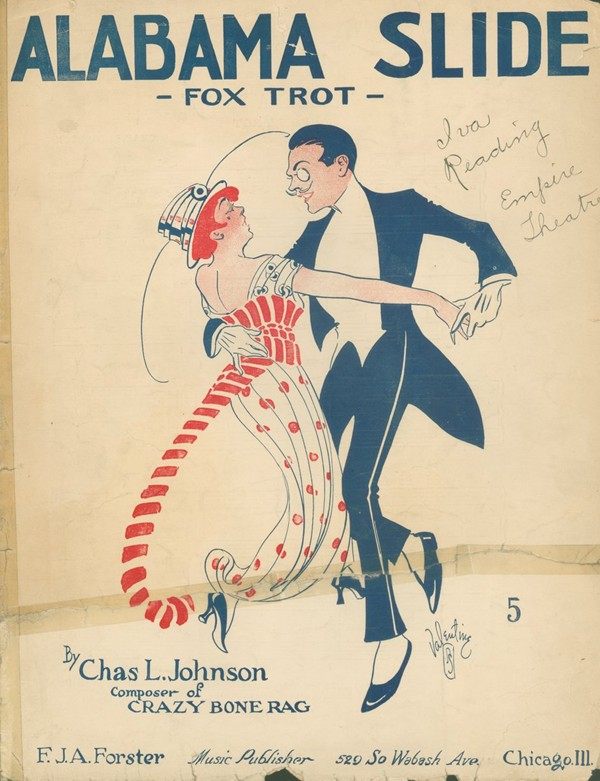

Low Brow and Middle Brow Culture

“It was a characteristic of the Jazz Age,” the novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote, “that it had no interest in politics at all.” What, then, were Americans interested in? Entertainment was Fitzgerald’s answer. Parlor games like Mah Jong and crossword puzzles became enormously popular during the 1920s. Contract bridge became the most durable of the new pastimes, followed closely by photography. Americans hit golf balls, played tennis, and bowled. Dance crazes like the fox trot, the Charleston, and the jitterbug swept the country.

New kinds of pulp fiction found a wide audience. Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan of the Apes became a runaway best-seller. For readers who felt concerned about urbanization and industrialization, the adventures of a lone white man in Darkest Africa revived the spirit of frontier individualism. Zane Grey’s novels, such as Riders of the Purple Sage, enjoyed even greater popularity, using the tried but true formula of romance, action, and a moralistic struggle between good and evil, all put in a western setting. Between 1918 and 1934, Grey wrote 24 books and became the best-known writer of popular fiction in the country.

Other readers wanted to be titillated, as evidence by the boom in “confession magazines.” Urban values, liberated women, and Hollywood films had all relaxed Victorian standards. Confession magazines rushed to fill the vacuum, purveying stories of romantic success and failure, divorce, fantasy, and adultery. Writers survived the censors’ cut by placing moral tags at the end of their stories, advising readers to avoid similar mistakes in their own lives.

Readers too embarrassed to pick up a copy of True Romance could read more urbane magazines such as The New Yorker or Vanity Fair offering entertainment, amusement, and gossip to those with sophisticated tastes. They could also join The Book of the Month Club or the Literary Guild, both of which were founded during this decade.

The Avant-Garde

Few decades have produced as many great works of art, music, or literature as the 1920s. At the decade’s beginning, American culture stood in Europe’s shadow. By the decade’s end, Americans were leaders in the struggle to liberate the arts from older canons of taste, form, and style. It was during the 1920s that Eugene O’Neill, the country’s most talented dramatist, wrote his greatest plays, and that authors William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Thomas Wolfe published their first novels.

American poets of the 1920s, such as Hart Crane, E. E. Cummings, Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes, Edna St. Vincent Millay, and Wallace Stevens experimented with new styles of punctuation, rhyme, and form. Likewise, artists like Charles Demuth, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Joseph Stella challenged the dominant realist tradition in American art and pioneered non-representational and expressionist art forms.

The 1920s marked America’s entry into the world of serious music. It witnessed the founding of fifty symphony orchestras and three of the country’s most prominent music conservatories—Julliard, Eastman, and Curtis Institution. This decade also produced America’s first great classical composers, including Aaron Copland and Charles Ives, and saw George Gershwin create a new musical forms by integrating jazz into symphonic and orchestral music.

World War I had left many American intellectuals and artists disillusioned and alienated. Neither Wilsonian idealism nor Progressive reformism appealed to America’s post-war writers and thinkers who believed that the crusade to end war and to make the world safe for democracy had been a senseless mistake. “Here was a new generation…” wrote the novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald in 1920 in This Side of Paradise, “grown up to find all Gods dead, all wars fought, all faiths in man shaken….”

During the 1920s, many of the nation’s leading writers exposed the shallowness and narrow-mindedness of American life. The United States was a nation awash in materialism and devoid of spiritual vitality: “a wasteland,” wrote the poet T.S. Eliot, “inhabited by hollow men.” No author offered a more scathing attack on middle class boorishness and smugness than Sinclair Lewis, who in 1930 became the first American to win the Nobel Prize for Literature. In Main Street (1920) and Babbitt (1922), he satirized the narrow-minded complacency and dullness of small town America, while in Elmer Gantry (1922), he exposed religious hypocrisy and bigotry.

As editor of Mercury magazine, H.L. Mencken wrote hundreds of essays mocking practically every aspect of American life. Calling the South a “gargantuan paradise of the fourth rate,” and the middle class the “booboisie,” Mencken directed his choicest barbs at reformers, whom he blamed for the bloodshed of World War I and the gangsters of the 1920s. “If I am convinced of anything,” he snarled, “it is that Doing Good is in bad taste.”

The writer Gertrude Stein defined an important group of American intellectuals when she told Ernest Hemingway in 1921, “You are all a lost generation.” Stein was referring to the expatriate novelists and artists who had participated in the Great War, only to emerge from the conflict convinced that it was an exercise in futility. In their novels, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Hemingway pointed toward a philosophy now known as “existentialism,” which maintains that life has no transcendent purpose and that each individual must salvage personal meaning from the void.

Hemingway’s fiction lionized toughness and “manly virtues” as a counterpoint to the softness of American life. In The Sun Also Rises (1926) and A Farewell to Arms (1929), he emphasized meaningless death and the importance of facing stoically the absurdities of the universe. In the conclusion of The Great Gatsby (1925), Fitzgerald gave pointed expression to an existentialist outlook: “so we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

Music of the 1920s

The novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald termed the 1920s “the Jazz Age.” With its earthy rhythms, fast beat, and improvisational style, jazz symbolized the decade’s spirit of liberation. At the same time, new dance styles arose, involving spontaneous bodily movements and closer physical contact between partners.

In fact, the 1920s was a decade of deep cultural division, pitting a more cosmopolitan, modernist, urban culture against a more provincial, traditionalist, rural culture. The decade witnessed a titanic struggle between an old and a new America as well as the rise of a modern consumer economy and mass entertainment. All of these themes were played out in the nation’s music.

Two appliances—the phonograph and radio—made popular music more accessible than ever before. The 1920s saw the record player enter American life in full force. Piano sales sagged as phonograph production rose from just 190,000 in 1923 to five million in 1929. The popularity of jazz, blues, and “hillbilly” music fueled the phonograph boom.

Thanks to the phonograph and radio, all Americans could now hear the full spectrum of American music —black and white, urban and rural, sophisticated and crude. There were comic songs (like “Yes, We Have No Bananas”), jazz, blues, ragtime, and fiddle music. It was “hot music” that fully supplanted the sentimental waltzes and parlor ballads, symphonic marches and Tin Pan Alley novelty numbers that had previously dominated middle-class musical tastes.

The “hot” music that became most popular during the 1920s was the product of cultural cross-pollination. A unique combination of African, Scottish, Irish, and Caribbean music created a music in the United States that was decisively different from music elsewhere in the world. What emerged was a music with drive—a strong rhythmic component that gets the feet stomping—and swerve—a bending of tempo, a swinging of the beat, and embellishments of the musical line.

With its fast pace and sharp edged, urgent beat, this music would ultimately pave the way for rock and roll.

The most popular form of music during the 1920s was jazz. Originating in New Orleans during the second decade of the twentieth century, jazz entered the cultural mainstream during the 1920s. Jazz challenged many cultural rules—musical and social. It emphasized improvisation over traditional structure, performer over composer, and black American experience over conventional white sensibilities.

Many of the pioneering jazz songs of the 1920s remain standards today. These include such hits, such as “Sweet Georgia Brown”, “Dinah,” and “Bye Bye Blackbird,” as well as Fats Waller’s “Honeysuckle Rose” and “Ain’t Misbehavin’,” Hoagy Carmichael and Mitchell Parish’s “Stardust,” George and Ira Gershwin’s “The Man I Love,” and Irving Berlin’s “Blue Skies.”

A series of new technologies transformed popular music during the 1920s: the microphone, the amplifier, electronic recording of sounds, and the radio. Development of the microphone and electronic recording meant that singers no longer had to belt out a song into a cone in order to make a record. Now singers could croon—that is, single softly, in a low voice. Amplifiers allowed performers to module their voice and to be heard in large theaters. The radio, in turn, made it much easier to distribute music.

Movies of the 1920s

In the late teens and ’20s, the movies began to shed their Victorian moralism, sentimentality, and reformism and increasingly expressed new themes: glamour, sophistication, exoticism, urbanity, and sex appeal. The movies of the 1920s exerted a powerful influence on American culture, values, and behavior.

During the 1920s, a sociologist named Herbert Blumer, interviewed students and young workers to assess the impact of movies on their lives, and concluded that the effect was to reorient their lives away from ethnic and working class communities toward a broader consumer culture. Observed one high school student: “The day-dreams instigated by the movies consist of clothes, ideas on furnishings and manners.” Said an African- American student: “The movies have often made me dissatisfied with my neighborhood because when I see a movie, the beautiful castle, palace…and beautiful house, I wish my home was something like these.”

Hollywood not only expressed popular values, aspirations, and fantasies, it also promoted cultural change.

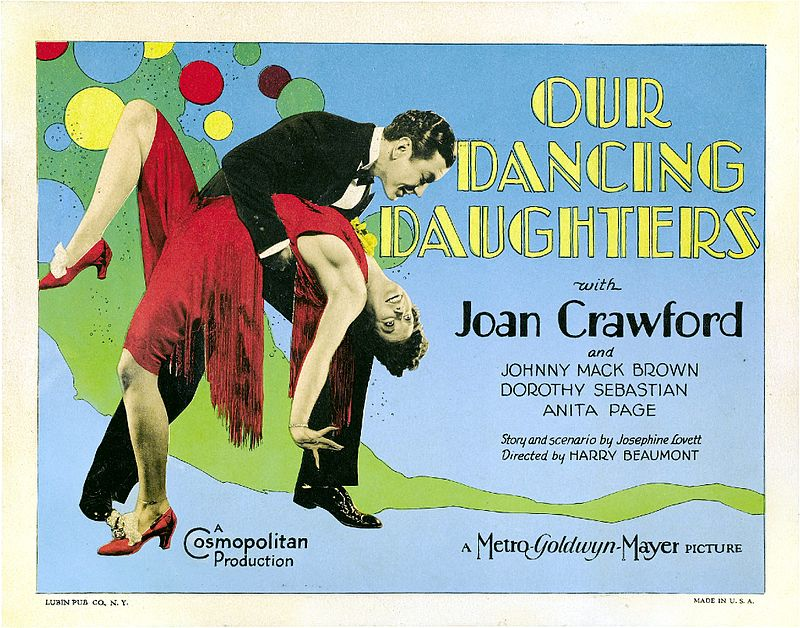

Our Dancing Daughters (1928)

This classic portrayal of the flapper who defies sexual convention and dances the Charleston till dawn was the film that made Joan Crawford a star. It also reveals the ambivalence that many Americans felt about the “revolution in morals and manners.” Crawford’s character’s flirting and drinking flapper masks her more conservative attitude toward love and sex.

The movies were never silent. Silent pictures were accompanied by music and sometimes a host who described the action.

Audiences did not seem to mind the lack of dialogue or sound effects. After all, silent movies were accessible to a mass audience including immigrants who spoke little English.

During the 1920s, sound abruptly transformed the movies. Suddenly, new genres—including the gangster movie, the musical, and comedies that relied on verbal wit rather than slapstick—proliferated. The movies also began to revel in the variety of accents and idioms: from Brooklyn, New England, Texas, among others, and Europe as well. Acting styles quickly changed. No longer did actors have to rely on body language to express emotions. Broad, exaggerated gestures gave way to more subtle ways of acting. Also, technical limitations on capturing sound made it necessary to restrict actors’ movements.

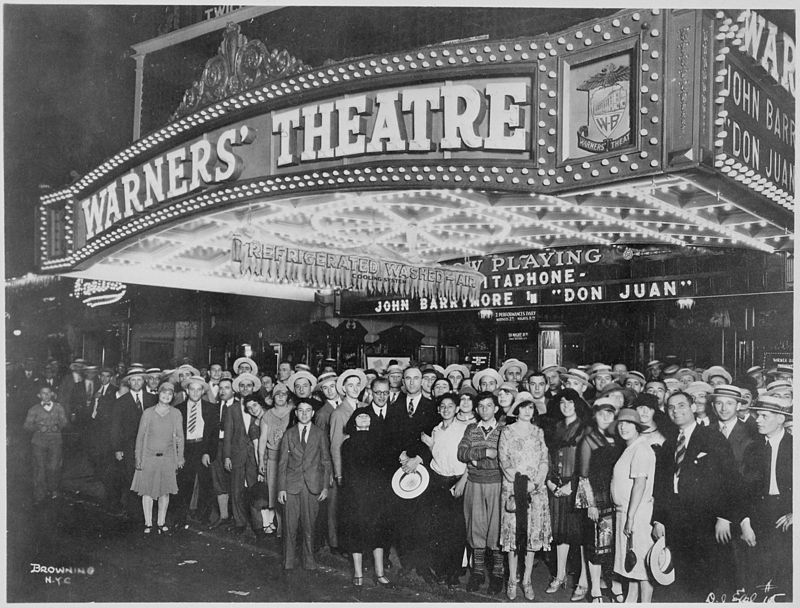

Talkies depended on a series of technological innovations. Engineers had to figure out how to synchronize visual image and sound. Live action demanded sensitive microphones and amplification.

Beginning in 1926, a large number of shorts featuring recorded sound appeared. These early works typically contained a number of songs, but few spoken words. A feature film, Don Juan, also was released, but while it had music and sound effects, it had no dialogue. The Jazz Singer, released in 1927, was the first true “talkie,” even though portions of the film are silent and used titles rather than dialogue to tell its story.