Politics During the 1920s

Politics During the 1920s

The expansion of government activities during World War I was reversed during the 1920s. Government efforts to break-up trusts and regulate business practices gave way to a new emphasis on partnerships between government and business.

In 1920, an Ohio political operator named Harry Daugherty offered a prediction about what would happen at that year’s Republican presidential nominating convention:

The convention will be deadlocked, and after the other candidates have gone their limit, some 12 or 15 men, worn out and bleary eyed for lack of sleep, will sit down about 2 o’clock in the morning around a table in a smoke-filled room in some hotel and decide the nomination. When the time comes, [Warren] Harding will be nominated.

Daugherty was right. In 1920, a divided Republican convention selected Harding, a U.S. Senator from Ohio, as its presidential nominee.

Harding’s presidency is best known for a series of scandals that marred his time in office. But he also had some genuine accomplishments. He pardoned the imprisoned Socialist party leader, Eugene Debs, and persuaded the steel industry to end the twelve-hour day and replace it with an eight-hour day. Harding also called an international disarmament conference in Washington that slowed down the arms race. At the end of the conference, a treaty was signed, that provided that, for every five battleships that the United States and Britain were each allowed to build, the Japanese could build three ships, and the Italians and the French could each build one-and-three-quarters ships.

The son of a poor Ohio farmer, Harding spent two years at a rural academy, Ohio Central College, and received a diploma at the age of sixteen. He taught school and sold insurance for several years before he bought a local newspaper. He guaranteed the newspaper’s success by mentioning every town resident in the paper at least twice a year. Harding described his editorial policy as “inoffensivism.” He later entered Republican politics, rising from lieutenant governor to U.S. Senator before being nominated for the presidency.

Harding made few major pronouncements during the campaign. The Republican Party followed an associate’s advice: “Keep Warren at home. If he goes out on tour, somebody’s sure to ask him questions, and Warren’s just the sort of damned fool that will try to answer them.” Harding largely confined his speeches to uncontroversial platitudes about the need to avoid moral crusades and return to “normalcy”:

“America’s present need is not heroics but healing; not nostrums, but normalcy; not revolution, but restoration; not agitation, but adjustment; not surgery, but serenity…”

Harding had few illusions about his qualifications for the presidency. “I am a man of limited talents from a small town,” he said. He appointed a number of sleazy and corrupt officials to office. His administration was marred by scandals involving bribes and kickbacks at the Justice Department and the Veterans Bureau. After his sudden death from a stroke in 1923, his administration’s biggest scandal, known as the Teapot Dome, was revealed. His Interior Secretary, Albert B. Fall, was sent to prison for accepting $360,000 in bribes for transferring U.S. naval oil reserves in Wyoming to oil operators in exchange for above ground petroleum storage. Private oil companies were also draining oil from federal lands.

Vice President Calvin Coolidge became president after Harding’s death. Coolidge had come to national attention in 1919, when, as governor of Massachusetts, he broke the Boston police strike after declaring: “there is no right to strike against the public interest, anytime, anywhere.”

Coolidge’s well-deserved nickname was “Silent Cal.” Some acquaintances wagered whether they could make him say more than two words. His answer: “You lose.” During the 1924 presidential race, reporters asked him whether he had any statement about the campaign. “No,” he replied. He was then asked whether he had anything to say about the world situation. “No,” he answered. Did he have anything to say about Prohibition? “No.” Then he told the reporters, “Now remember, don’t quote me.” At the end of his presidency, he was asked whether he had a farewell message for the American people, he paused and said, “Good-bye.”

Coolidge slept ten hours a night, napped every afternoon, and seldom worked more than four hours a day. He spoke out ardently on behalf of the nation’s business culture. “The man who builds a factory builds a temple,” said Coolidge. “The man who works there, worships there.” The president was convinced that the formula for economic prosperity was simple: “The chief business of the American people is business. If government kept its hands off the economy, business would prosper.” As president, Coolidge sought to promote economic growth through an alliance between government and business.

Among the most notable acts of his presidency were vetoes of bills to assist farmers in developing government power plants along the Tennessee River. The best known accomplishment of his presidency was the Kellogg-Briand Pact, an international agreement outlawing the use of force to settle international disputes. Embodying the anti-war sentiment of the 1920s, this agreement lacked any methods of enforcement.

The Democratic Convention of 1924

In 1924, Democratic prospects in the upcoming presidential election seemed promising. The administration of Republican Calvin Coolidge was rocked by a scandal, the Teapot Dome, which involved secret leasing of the Navy’s oil fields to private businesses.

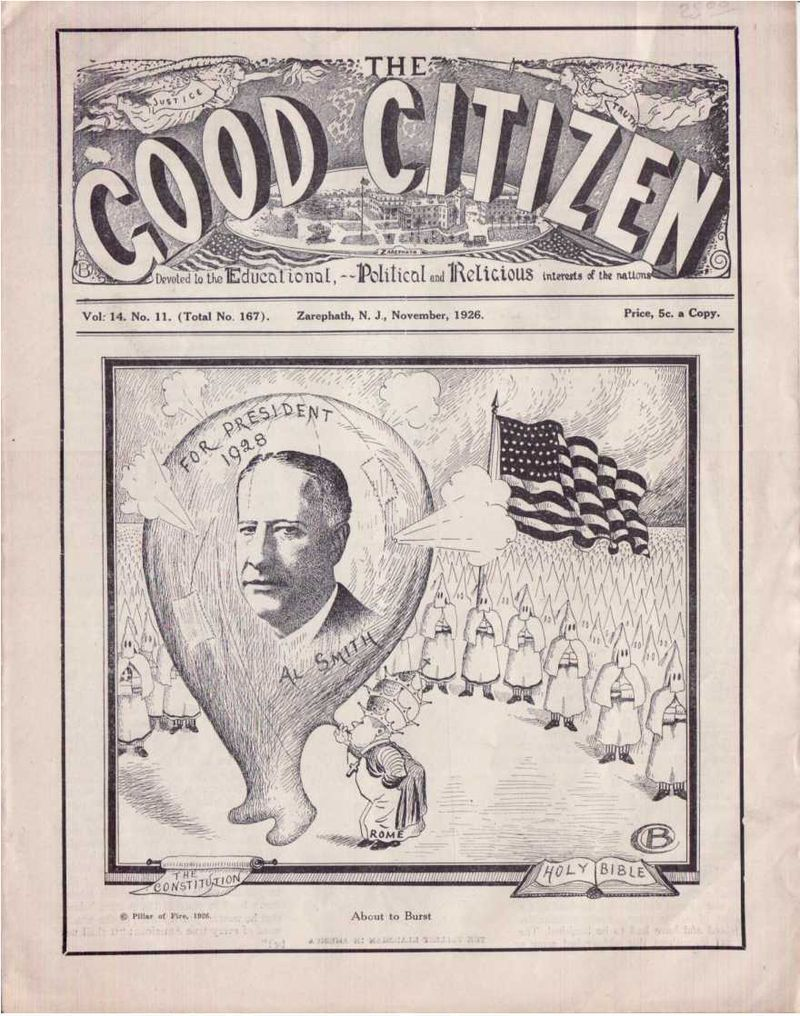

But the Democratic Party was deeply divided, especially between its urban and rural wings. The Democratic Party was an uneasy coalition of diverse elements: Northerners and Southerners, Westerners and Easterners, Catholics and Jews and Protestants, conservative landowners and agrarian radicals, progressives and big city machines, urban cosmopolitans and small-town traditionalists. On one side were defenders of the Ku Klux Klan, prohibition, and fundamentalism. On the other side were northeastern Catholics and Jewish immigrants and their children. A series of issues that bitterly divided the country during the early 1920s were on display at the 1924 Democratic Convention held at Madison Square Garden in New York City from June 24 to July 9, 1924. These issues included prohibition and religious and racial tolerance. The Northeasterners wanted an explicit condemnation of the Ku Klux Klan.

The two leading candidates symbolized a deep cultural divide. Al Smith, New York’s governor, was a Catholic and an opponent of prohibition and was bitterly opposed by Democrats in the South and West. Former Treasury Secretary William Gibbs McAdoo, a Protestant, defended prohibition and refused to repudiate the Ku Klux Klan, making himself unacceptable to Catholics and Jews in the Northeast.

Newspapers called the convention a “Klanbake,” as pro-Klan and anti-Klan delegates wrangled bitterly over the party platform. The convention opened on a Monday and by Thursday night, after 61 ballots, the convention was deadlocked. The next day, July 4, some 20,000 Klan supporters wearing white hoods and robes held a picnic in New Jersey. One speaker denounced the “clownvention in Jew York.” They threw baseballs at an effigy of Al Smith. A cross-burning culminated the event.

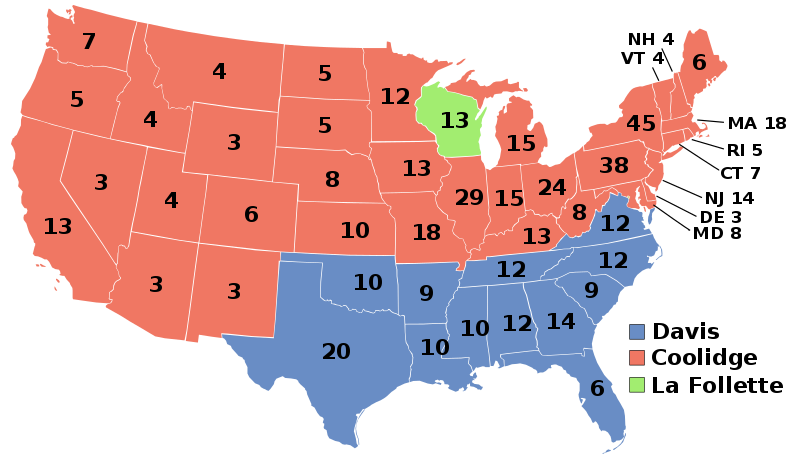

Al Smith and William Gibbs McAdoo withdrew from contention after the 99th ballot. On the 103rd ballot, the weary convention nominated John W. Davis of West Virginia, formerly a U.S. Representative from West Virginia, Solicitor General for the United States, and U.S. Ambassador to Britain under President Woodrow Wilson. The nomination proved worthless. Liberals deserted the Democrats and voted for Robert LaFollette, a third party candidate. Apathy and disgust kept many home, and just half of those eligible went to the polls. The Democrat candidate, John Davis, received eight million votes. The Republican candidate, incumbent president Calvin Coolidge, received fifteen million votes.

The Election of 1928

At stake in the presidential election of 1928 was whether the United States could elect a Catholic president.

In 1928, the Democrats were resolved to avoid a repeat of the party divisions of 1924. The convention was held in Houston. The party platform stood in favor of aid to farmers and workers, collective bargaining, abolition of labor injunctions, and stricter regulation of power companies. Al Smith was nominated for president. A Southern advocate of prohibition was chosen for the vice president.

Born in 1873, Al Smith was an Irish Catholic from New York’s Lower East Side. For almost a decade as governor of the nation’s largest state, he had made New York a model for efforts to use government to improve the public’s well-being. Under his leadership, New York granted women a forty-hour work week and instituted the nation’s first public housing program. He also established state parks and a system of public hospitals.

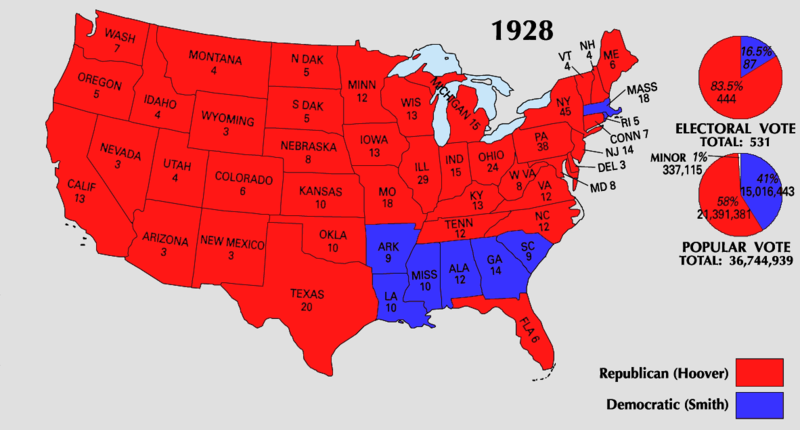

Smith doubled the Democratic vote of 1924. But it was not enough. He lost New York and much of the South.

There was no single cause for the defeat. Economic prosperity and Prohibition played a part. However, it appears that anti-Catholicism did him in. Minister’s called New York “Satan’s seat” Smith was attacked as the candidate in support of saloons, prostitution, and gambling. Smith refused to pretend that he was anything other than what he was: a Catholic, who kept a picture of the Pope over his desk.

Nevertheless, Smith did make gains. He carried Massachusetts, the first Democrat to do so since the Civil War. He awakened a great army of immigrant voters in the big cities—Italian, Jewish, Polish, as well as Irish. And, he helped shift the African American vote toward the Democrats.

Herbert Hoover

In the presidential election of 1928, Al Smith was defeated by Herbert Hoover, a wealthy mining engineer who had served as commerce secretary for both Presidents Harding and Coolidge.

Hoover had headed European relief efforts after World War I. “He is certainly a wonder,” exclaimed the young Franklin D. Roosevelt, “and I wish we could make him president of the United States. There couldn’t be a better one.”

As Secretary of Commerce, Hoover proposed to eliminate destructive economic competition through the establishment of trade associations working in cooperation with government. By 1929, more than 2,000 trade associations had been created.

When Hoover campaigned for the presidency, the country seemed headed toward ever greater economic prosperity. In a campaign speech, he said:

We in America today are nearer to the final triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of any land. We shall soon, with the help of God, be in sight of the day when poverty will be banished from this nation.

In his first steps in office, Hoover created the Federal Farm Board to increase farmers’ income. He also called for a system of private, voluntary old-age pensions. The collapse of the stock market, however, shattered his vision of a private economy operating largely free from government intervention.