Traditionalism and Modernism

Fundamentalism and Pentecostalism

Religion was a pivotal cultural battleground during the 1920s. The roots of this religious conflict were planted in the late nineteenth century. Before the Civil War, the Protestant denominations were united in a belief that the findings of science confirmed the teachings of religion. But during the 1870s, a lasting division occurred in American Protestantism over Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. Religious modernists argued that religion had to be accommodated to the teachings of science, while religious traditionalists sought to preserve the basic tenets of their religious faith.

As an organized movement, Fundamentalism is said to have started with a set of twelve pamphlets, The Fundamentals: A Testimony, published between 1909 and 1912. Financed by two wealthy laymen, the pamphlets were to be sent free to “every pastor, evangelist, missionary, theological student, Sunday School superintendent, Y.M.C.A. and Y.W.C.A. secretary in the English speaking world.” Eventually, some three million copies were distributed. The five fundamentals in these volumes testified to the infallibility of the literal interpretation of the Bible and the actuality of the virgin birth, the atonement, the resurrection, and the second coming of Christ. Some early Fundamentalists regarded Catholics as agents of the Antichrist.

Pentecostalism, another current in Protestant revivalism, began on New Year’s Day in 1901. A female student at Bethel Bible College in Topeka, Kansas, began speaking in tongues, unintelligible speech that accompanies religious excitation. To many evangelicals, speaking in tongues was evidence of the descent of the Holy Spirit into a believer.

Pentecostals rejected the idea that the age of miracles had ended. During the 1920s, many Americans became aware of Pentecostalism as charismatic faith healers claimed to be able to cure the sick and to allow the crippled to throw away their crutches. Pentecostalism spread particularly rapidly among lower middle-class and poorer Protestants who sought a more spontaneous and emotional religious experience than that offered by the mainstream religious denominations. The most prominent of the early Pentecostal revivalists was Aimee Semple McPherson.

The Fundamentalist and Pentecostal movements arose in the early twentieth century as a backlash against modernism, secularism, and scientific teachings that contradicted their religious beliefs. Early fundamentalist doctrine attacked competing religions—especially Catholicism, which it portrayed as an agent of the Antichrist—and insisted on the literal truth of the Bible, a strict return to fundamental principles, and a thoroughgoing rejection of modernity.

Between 1921 and 1929, Fundamentalists introduced 37 anti-evolution bills into twenty state legislatures. The first law to pass was in Tennessee.

During the summer of 1925, John Scopes, a high school teacher in Dayton, Tennessee, was tried for violating the prohibition on the teaching of evolution in tax-supported schools. The statute forbade the teaching in public schools of any scientific theory that denied the literalness of the Biblical account of creation. The Scopes case raised the legal issue of the validity of a law that seemed to violate the constitutional separation of church and state.

Hollywood Versus History

To see the 1960 Hollywood version of the Scopes Trial’s court scene, click below

The Scopes Trial

The Scopes Trial is one of the best known in American history because it symbolizes the conflict between science and theology, faith and reason, and individual liberty and majority rule. The object of intense publicity, the trial was seen as a clash between urban sophistication and rural fundamentalism. The trial was further popularized by the 1955 play, Inherit the Wind, which became a hit film in 1960. The play and subsequent movie cast the trial as a struggle for truth and freedom against repression and ignorance.

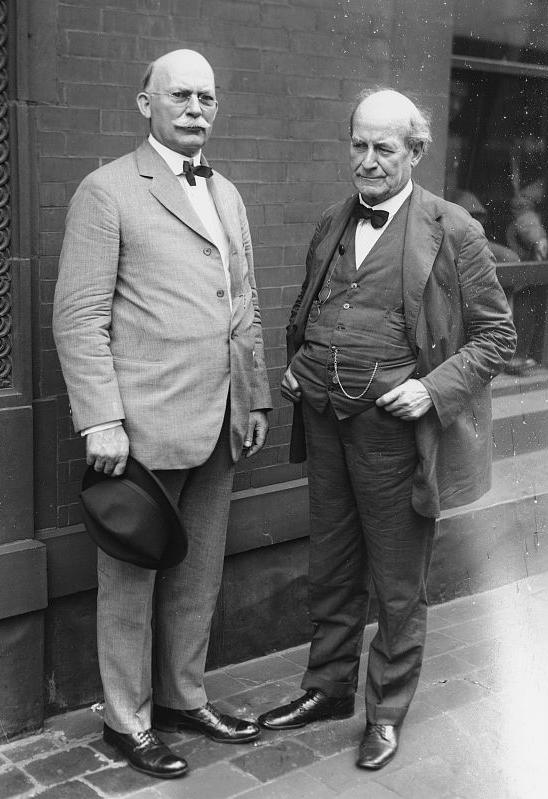

In the summer of 1925, a young schoolteacher named John Scopes stood trial in Dayton, Tennessee, for violating the state law against the teaching of evolution. Two of the country’s most famous attorneys faced off in the trial. William Jennings Bryan, sixty-five years old and a three-time Democratic presidential nominee, prosecuted; sixty-seven-year-old Clarence Darrow, who was a staunch agnostic and who had defended Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb in a notorious murder trial the year before, represented the defense. Bryan declared that “the contest between evolution and Christianity is a duel to the death.”

The five-year-old American Civil Liberties Union had taken out newspaper advertisements offering to defend anyone who flouted the Tennessee law. George Rappelyea, a Dayton, Tennessee, booster, realized that the town would get enormous attention if a local teacher was arrested for teaching evolution. He enlisted John Scopes, a science teacher and football coach, who arranged to teach from George Hunter’s Civic Biology, a high school textbook promoting Charles Darwin’s arguments in The Descent of Man.

The trial was marked by hoopla and a carnival-like atmosphere. Thousands of people swelled the town of a thousand. For twelve days in July, 1925, 100 reporters sent dispatches.

The trial judge had prohibited the defense from using scientists as witnesses. So, on the trial’s seventh day, the defense team called Bryan to testify as an expert on the Bible. Darrow subjected Bryan to a withering cross-examination. He got Bryan to say that Creation was not completed in a week, but over a period of time that “might have continued for millions of years.”

The play, Inherit the Wind, would caricature Bryan as a Bible-thumping buffoon, but in actuality, Bryan’s position was complex. He opposed the mandated teaching of evolution in public schools because he thought the people should exercise local control over school curricula. He also opposed Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection because these ideas had been used to defend laissez-faire capitalism on the grounds that a perfectly free market promotes the “survival of the fittest.” As early as 1904, Bryan had denounced social Darwinism as “the merciless law by which the strong crowd out and kill off the weak.”

In addition, Bryan opposed Darwinism as justification for war and imperialism. In The Descent of Man, Darwin has argued that “at some future period, not very distant as measured by centuries, the civilized races of man will almost certainly exterminate and replace the savage races.” The textbook that Scopes taught from, Civic Biology, identified five “races of man”: Ethiopian, Malay, American Indian, and Mongolian, and “finally, the highest type of all, the Caucasians, represented by the civilized white inhabitants of Europe and America.” Bryan was also unhappy with Darwin’s assumption that the entire evolutionary process was purposeless and not the product of a larger design.

Not a Biblical literalist, Bryan was aware of serious scientific difficulties with Darwinism, such as Darwin’s theory that slight, random variations were enough to generate life from non-life to produce a vast array of biological species. But Bryan mistook the lack of consensus about the mechanisms that Darwin advanced to explain the evolutionary process for a lack of scientific support for the concept of evolution itself.

The day after this exchange, Darrow changed his client’s plea to guilty. Scopes was convicted and fined $100. However, the conviction was thrown out on a technicality by the Tennessee Supreme Court: that the judge, and not the jury, had determined the $100 fine. In 1967, the Supreme Court struck down Tennessee’s anti-evolution law for violating the Constitution’s prohibition against the establishment of religion.

Five days after the trial’s conclusion, Bryan died of apoplexy. The journalist H.L. Mencken wrote of Bryan: “He came into life a hero, a Galahad, in bright and shining armor. He was passing out a poor mountebank.” As for Scopes, he left teaching and became a chemical engineer in the oil industry. He died at age seventy in 1970.

The Scopes trial resulted in two enduring conclusions: that legislatures should not restrain the freedom of scientific inquiry, and that society should respect academic freedom.

Evolution

Evolution was a major point of contention during the 1920s.

Read the following quotations and then explain why you think evolution became such a flashpoint for controversy.

What has religion to do with facts? Nothing. Is there any such thing as Methodist mathematics, Presbyterian botany, Catholic astronomy, or Baptist biology? What has any form of superstition or religion to do with a fact or with any science? Nothing but to hinder, delay or embarrass. -Robert G. Ingersoll

Be it Enacted, by the General Assembly of the State of Tennessee, that it shall be unlawful for any teacher in any of the universities, normals, and all other public schools in the State, which are supported in whole or in part by the public school funds of the State, to teach the theory that denies the story of the divine creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals. -Tennessee state law

What is Darwinism? It is Atheism. -Charles Hodge

Evolution is God’s way of doing things. -John Fiske

Evolution, applied to religion, will influence it only as the hidden temples are restored, by removing the sands which have drifted in from the arid deserts of scholastic and medieval theologies. It will change theology, but only to bring out the simple temple of God in clearer and more beautiful lines and proportions. -Reverend Henry Ward Beecher

The first objection to Darwinism is that it is only a guess and was never anything more…. The second objection to Darwin’s guess is that it has not one syllable in the Bible to support it. This ought to make Christians cautious about accepting it without thorough investigation…. Third–Neither Darwin nor his supporters have been able to find a fact in the universe to support their hypothesis. With millions of species, the investigators have not been able to find one single instance in which one species has changed into another…Theistic evolution may be defined as an anesthetic which deadens the patient’s pain while atheism removes his religion. -William Jennings Bryan

Here we find to-day as brazen and as bold an attempt to destroy learning as was ever made in the Middle Ages and the open difference is we have not provided that malefactors shall be burned at the stake. But here is time for that, your Honor. We have to approach these things gradually…. If to-day you can take a thing like evolution and make it a crime to teach it in the public school…at the next session you may ban books and newspapers…. Ignorance and fanaticism are ever busy and need feeding. Always they are anxious and gloating for more. -Clarence Darrow