Anxiety about Immigrants

Sacco and Vanzetti

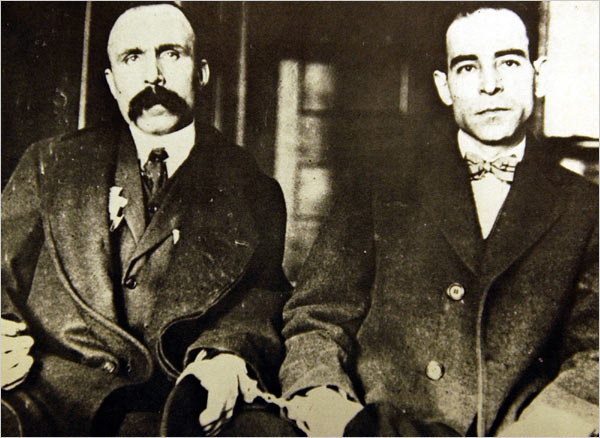

During the twentieth century, a number of trials excited widespread public interest. One of the first “trials of the century” was the case of Nicola Sacco, a 32-year-old shoemaker, and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, a 29-year-old fish peddler, who were accused of double murder. On April 15, 1920, a paymaster and a payroll guard carrying a factory payroll of $15,776 were shot to death during a robbery in Braintree, Massachusetts, near Boston. About three weeks later, Sacco and Vanzetti were charged with the crime. Their trial aroused intense controversy because it was widely believed that the evidence against the men was flimsy, and that they were being prosecuted for their immigrant background and their radical political beliefs. Sacco and Vanzetti were Italian immigrants and avowed anarchists who advocated the violent overthrow of capitalism.

It was the height of the post-World War I Red Scare, and the atmosphere was seething with anxieties about Bolshevism, aliens, domestic bombings, and labor unrest. Revolutionary upheavals had been triggered by the war, and one-third of the U.S. population consisted of immigrants or the children of immigrants.

U.S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer had ordered foreign radicals rounded up for deportation. Just three days before Sacco and Vanzetti were arrested, one of the people seized during the Palmer raids, an anarchist editor, had died after falling from a fourteenth floor window of the New York City Department of Justice office. The police, judge, jury, and newspapers were deeply concerned about labor unrest.

No witnesses had gotten a good look at the perpetrators of the murder and robbery. The witnesses described a shootout in the street and the robbers escaping in a Buick, scattering tacks to deter pursuers. Anti-immigrant and anti-radical sentiments led the police to focus on local anarchists.

Sacco and Vanzetti were followers of Luigi Galleani, a radical Italian anarchist who had instigated a wave of bombings against public officials just after World War I. Carlo Valdinoci, a close associate of Galleani, had blown himself up while trying to plant a bomb at Attorney General Palmer’s house. The powerful blast, which largely destroyed Palmer’s house, hurled several neighbors from their beds in nearby homes. Though not injured, Palmer and his family were thoroughly shaken by the blast.

After the incident Sacco and Vanzetti acted nervously, and the arresting officer testified that Sacco and Vanzetti were reaching for weapons when they were apprehended. But neither man had a criminal record. Plus, a criminal gang had been carrying out a string of armed robberies in Massachusetts and Rhode Island.

Police linked Sacco’s gun to the double murder, the only piece of physical evidence that connected the men to the crime. The defense, however, argued that the link was overstated.

In 1921, Sacco and Vanzetti were convicted in a trial that was marred by prejudice against Italians, immigrants, and radical beliefs. The evidence was ambiguous as to the pairs’ guilt or innocence, but the trial was a sham. The prosecution played heavily on the pairs’ radical beliefs. The men were kept in an iron cage during the trial. The jury foreman muttered unflattering stereotypes about Italians. In his instructions to the jury, the presiding judge urged the jury to remember their “true American citizenship.”

The pair was electrocuted in 1927. As the guards adjusted his straps, Vanzetti said in broken English:

I wish to tell you I am innocent and never connected with any crime… I wish to forgive some people for what they are now doing to me.

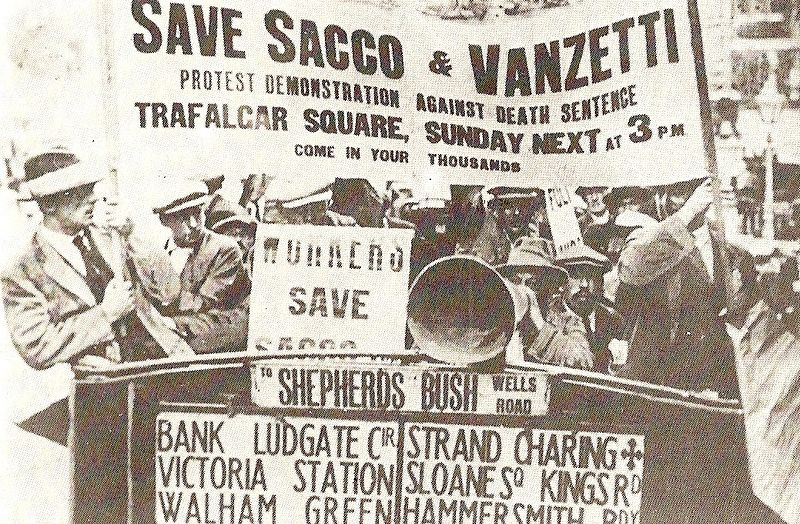

Their execution divided the nation and produced an uproar in Europe. Harvard Law Professor and later U.S. Supreme Court Justice, Felix Frankfurter, condemned the prejudice of the presiding judge (who reportedly said in 1924, “Did you see what I did with those anarchistic bastards the other day?”) and procedural errors during the trial. These errors included the prosecution’s failure to disclose eyewitness evidence favorable to the defense. A commission that included the presidents of Harvard and MIT defended the trial’s fairness.

Today, many historians now believe Sacco was probably guilty and Vanzetti was innocent but that the evidence was insufficient to convict either one.

Immigration Restriction

Before World War I, American industry, steamship companies, and railroads promoted immigration and financed groups opposed to immigration restriction. The United States did institute registration and literacy requirements for immigrants. Yet, opponents of restriction succeeded in blocking efforts to establish immigration quotas.

World War I revealed that the economy could function effectively without foreign immigration. Opposition to immigration restriction withered away. Not only had World War I demonstrated that immigrants had become “Americanized,” but with the establishment of new European nation states, interest in European politics faded away. While some opponents of immigration argued that it threatened the nation’s culture, most of the arguments advanced against immigration were economic. Among the chief proponents of immigration restriction were the unions of the American Federation of Labor. Organized labor feared that American workers’ wages would decline if unskilled immigrant workers flooded the labor market. Meanwhile, many businessmen feared dangerous foreign radicals.

During the 1920s, most ethnic groups agreed that the overall volume of immigration should be reduced. The issue remained: how to distribute the immigration quotas. A compromise was easily reached: make the quotas proportionate to the current population, so that future immigration would not change the balance of ethnic groups.

In 1924, Congress reduced the number of immigrants allowed into the United States each year to two percent of each nationality group counted in the 1890 census. It also barred Asians entirely.

100 Percent Americanism

During a Columbus Day speech in 1915, former President Theodore Roosevelt insisted that “there is no room in this country for hyphenated Americanism.” Speaking before the United States had entered World War I, he declared:

The one absolutely certain way of bringing this nation to ruin, of preventing all possibility of its continuing to be a nation at all, would be to permit it to become a tangle of squabbling nationalities, an intricate knot of German-Americans, Irish-Americans, English-Americans, French-Americans, Scandinavian-Americans or Italian-Americans, each preserving its separate nationality, each at heart feeling more sympathy with Europeans of that nationality, than with the other citizens of the American Republic.

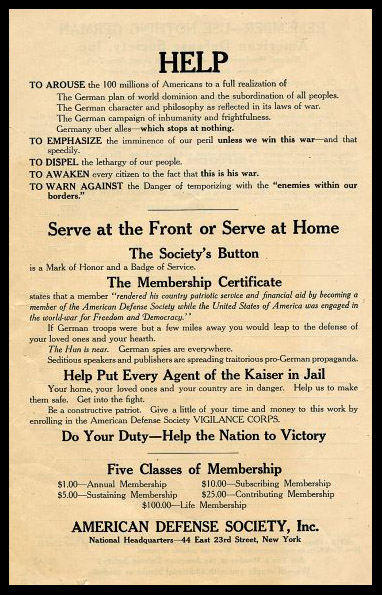

American entry into the war fanned the flames of anti-immigrant sentiment, encouraging restrictive legislation and even violence. Organizations such as the National Security League and the American Defense Society encouraged the burning of German books and “Americanizing” German names. A 1917 statute declared that no material on the war could be published in a foreign language newspaper or magazine unless a translation was approved by a local postmaster. There was pressure on churches to abandon German language use during religious services.

In Iowa, the governor prohibited the speaking of German on streetcars, over the telephone, or in any public place. In Wyoming, a German speaker was hanged, cut down while still alive, and made to kneel and kiss the American flag. Near St. Louis, a German immigrant was lynched before a 500-person mob.

A new phrase entered the language: 100 percent Americanism. The goal was to stamp out all traces of Old World identity, loyalties, and customs.

After the war, schools, settlement houses, YMCAs, church, and patriotic and fraternal groups established Americanization programs, offering instruction in English, American history, and personal hygiene. Congress, in 1917 overrode a presidential veto to mandate a literacy test for prospective immigrants. In 1921, Congress imposed a numerical limit on immigration accompanied by a quota system based on national origin.

The quest for 100 percent Americanism was a fool’s errand, as a prominent anthropologist, Ralph Linton, observed in 1936. American culture was a mish-mash of diverse cultural influences. When an American awakes, he or she “throws back covers made from cotton, domesticated in India, or linen, domesticated in the Near East, or wool from sheep, also domesticated in the Near East. He slips into his moccasins, invented by the Indians of the Eastern woodlands.” An American then “takes off his pajamas, a garment invented in India, and washes with soap invented by the ancient Gauls.” A man “then shaves, a masochistic rite which seems to have been derived from either Sumer or ancient Egypt.”

Every facet of life has multiple roots and sources. Our shoes are “made from skins tanned by a process invented in ancient Egypt and cut to a pattern derived from the classical civilizations of the Mediterranean.” Glass was also invented in Egypt. Our food, too, has diverse heritage: Cantaloupes originally came from Persia, watermelon from Africa, coffee from Abyssinia, sugar from India.

In recent years, the quest for cultural purity has taken a new form, as activists have denounced “cultural appropriation—the claim that certain cultural elements have been stolen or expropriated or trivialized by the dominant culture. There were protests over General Tso’s Chicken at Oberlin College in 2015 (a dish first concocted in 1952 for an American admiral visiting Taiwan) and over a white woman wearing hoop earrings (which apparently originated in Nimrud, in ancient Assyria).

Genuine examples of cultural appropriation exist. These include the “covering” of songs of black or Hispanic artists by white performers or the assumption of hairstyles, like cornrows, by non-African Americans.

A recent controversy has erupted over a painting by Dana Schutz, a well-known New York artist. Entitled “Open Casket,” it shows the mutilated body of Emmett Till, a fourteen year old who was murdered by two white men in Mississippi in 1955. The painting’s critics accuse the artists of transmuting “Black suffering into profit and fun” and aestheticizing an awful act of injustice.