Race

History as it Happened

Race Riots

Some of the most vicious racial violence in American history took place between 1917 and 1923. The hostility stemmed partly from dramatic shifts in the demography of race. Black workers who had been historically confined to the South had begun to move north and to compete with whites for factory jobs. These black workers often found jobs as strikebreakers, the only way many could get hired. In addition, animosity flared as black veterans returned from World War I insisting on the civil rights that they had fought for in Europe. In Chicago, Illinois, Longview, Texas, Omaha, Nebraska, Rosewood, Florida, Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Washington, D.C., white mobs burned and killed in black neighborhoods.

In Tulsa, forty city blocks were leveled and twenty-three African American churches and a thousand homes and businesses were destroyed. In 1921, Tulsa (about twelve percent black) had the Southwest’s most prosperous African American business community. Booker T. Washington had called this area “the black Wall Street.”

The violence erupted after a nineteen-year-old African American bootblack was arrested for supposedly assaulting a white, female teenager working as an elevator operator. Police later concluded that the young man had stumbled into the woman as he was getting off the elevator. An inflammatory newspaper article that helped touch off the violence was headlined “To Lynch Negro Tonight.”

The death toll from the violence is still disputed. A government report said that twenty-six blacks and ten whites had died, and another 317 were injured. A recent scholarly study concluded that black deaths approached 100 and may have been much higher.

Another incident of racial violence took place on New Year’s Day in 1923, in the tiny black settlement of Rosewood, Florida. A white mob, from as far away as Georgia and purportedly searching for an alleged rapist, burned the town of 150 residents. Only one structure, a house owned by the community’s only white resident, was not destroyed. Newspaper accounts differ on the total number of people killed; one report lists seven deaths, another twenty-one. One Rosewood resident, a blacksmith, was hanged.

Lacking hard evidence, historians have had to rely on oral history. One man, who was eleven years old at the time of the attack, recalled his father’s reports of the violence. He described a black man who was forced to dig his own grave, then was shot and shoved into it. A man was hanged from a tree in his front yard when he told a posse that he could not lead them to the alleged rapist, and a pregnant woman was shot as she tried to crawl under her porch for protection. In 1994, the state of Florida paid $2.1 million in reparations.

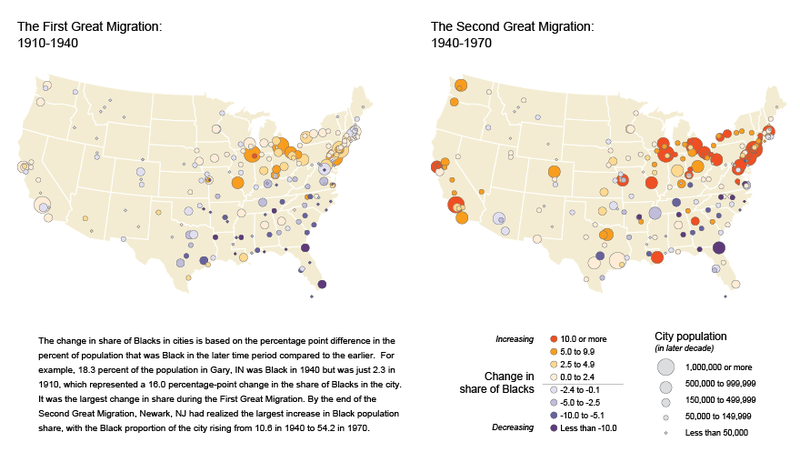

The Great Migration

The racial composition of the nation’s cities underwent a decisive change during and after World War I. In 1910, three out of every four black Americans lived on farms, and nine out of ten lived in the South. World War I changed that profile. Hoping to escape tenant farming, sharecropping, and peonage, 1.5 million Southern blacks moved to cities. During the 1910s and 1920s, Chicago’s black population grew by 148 percent, Cleveland’s by 307 percent, Detroit’s by 611 percent.

Access to housing became a major source of friction between blacks and whites during this massive movement of people. Many cities adopted residential segregation ordinances to keep blacks out of predominantly white neighborhoods. In 1917, the Supreme Court declared municipal resident segregation ordinances unconstitutional. In response, whites resorted to the restrictive covenant, a formal deed restriction binding white property owners in a given neighborhood not to sell to blacks. Whites who broke these agreements could be sued by “damaged” neighbors. Not until 1948 did the Supreme Court strike down restrictive covenants.

Confined to all-black neighborhoods, African Americans created cities-within-cities during the 1920s. The largest was Harlem, in upper Manhattan, where 200,000 African Americans lived in a neighborhood that had been virtually all-white fifteen years before.

African American Protests

In World War I, a higher proportion of black soldiers than white soldiers had lost their lives: 14.4 percent black compared to 6.3 percent white. Many African Americans believed that this sacrifice would be repaid when the war was over. In the words of one Texan, “Our second emancipation will be the outcome of this war.” It was not to be. The federal government denied black soldiers the right to participate in the victory march down Paris’s Champs-Elysees boulevard, even though black troops from European colonies marched. Ten African American soldiers were among the seventy blacks lynched in 1919. Twenty-five anti-black riots took place that year.

African Americans did not respond passively to these outrages. Even before the war, African Americans had stepped up protests against discrimination. The National Urban League, organized in 1911 by social workers, white philanthropists, and black leaders, concentrated on finding jobs for urban African Americans. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) won important Supreme Court decisions against the grandfather clause (1915) and restrictive covenants (1917). The NAACP also fought school segregation in northern cities during the 1920s and lobbied hard, though unsuccessfully, for a federal anti-lynching bill.

No black leader was more successful in touching the aspirations and needs of the mass of African Americans than Marcus Garvey. A flamboyant and charismatic figure from Jamaica, Garvey rejected integration and preached racial pride and black self-help. A staunch advocate of black economic solidarity and Pan-Africanism, he called on all people of African descent to unite politically and economically. Garvey declared that Jesus Christ and Mary were black; he exhorted his followers to glorify their African heritage and revel in the beauty of their black skin. “We have a beautiful history,” he told his followers, “and we shall create another one in the future.”

In 1917, Garvey moved to New York and organized the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), the first mass movement in African American history. By the mid-1920s, Garvey’s organization had 700 branches in 38 states and the West Indies. The organization also published a newspaper with as many as 200,000 subscribers. The UNIA operated grocery stores, laundries, restaurants, printing plants, clothing factories, and a steamship line.

In the mid-1920s, Garvey was charged with mail fraud, jailed, and finally deported. Still, the “Black Moses” left behind a rich legacy. At a time when magazines and newspapers overflowed with advertisements for hair straighteners and skin lightening cosmetics, Garvey’s message of racial pride struck a responsive chord in many African Americans.

The Harlem Renaissance

The movement for black pride found its cultural expression in the Harlem Renaissance, the first self-conscious literary and artistic movement in African American history.

For over three decades, African Americans had shown increasing interest in black history and African American folk culture. As early as the 1890s, W.E.B. Du Bois, Harvard’s first African American Ph.D., began to trace black culture in the United States to its African roots. Fisk University’s Jubilee Singers introduced Negro spirituals to the general public. The American Negro Academy organized in 1897, promoted African American literature, arts, music, and history. A growing spirit of racial pride was evident. A group of talented writers, including Charles Chestnut, Paul Lawrence Dunbar, and James Weldon Johnson, explored life in black communities; the first Negro dolls appeared, and all-Negro towns were founded in Whitesboro, New Jersey, and Allensworth, California.

Signs of growing racial consciousness proliferated during the 1910s. Fifty new black newspapers and magazines appeared in that decade, bringing the total to 500. The Associated Negro Press, the first national black press agency, was founded in 1919. In 1915, Carter Woodson, a Harvard Ph.D., founded the first permanent Negro historical association, the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, and began publication of the Journal of Negro History.

During the 1920s, Harlem became the capital of black America, attracting black intellectuals and artists from across the country and the Caribbean. Soon, the Harlem Renaissance was in full bloom. The poet Countee Cullen eloquently expressed black artists’ long-suppressed desire to have their voices heard: “Yet do I marvel at a curious thing: To make a poet black, and bid him sing!”

Many of the greatest works of the Harlem Renaissance sought to recover links with African and folk traditions. In “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” the poet Langston Hughes reaffirmed his ties to an African past: “I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it.” In his book Cane (1923), Jean Toomer, the grandson of P.B.S. Pinchback, who served briefly as governor of Louisiana during Reconstruction, blended realism and mysticism, and poetry and prose to describe the world of the black peasantry in Georgia. In the ghetto of Washington, D.C., Zora Neale Hurston, a Columbia University trained anthropologist, incorporated rural black folklore and religious beliefs into her stories.

A fierce racial conscious and a powerful sense of racial pride animated the literature of the Harlem Renaissance. The West Indian-born poet Claude McKay expressed the new spirit of defiance and protest with militant words: “If we must die—oh let us nobly die…dying, but fighting back!”

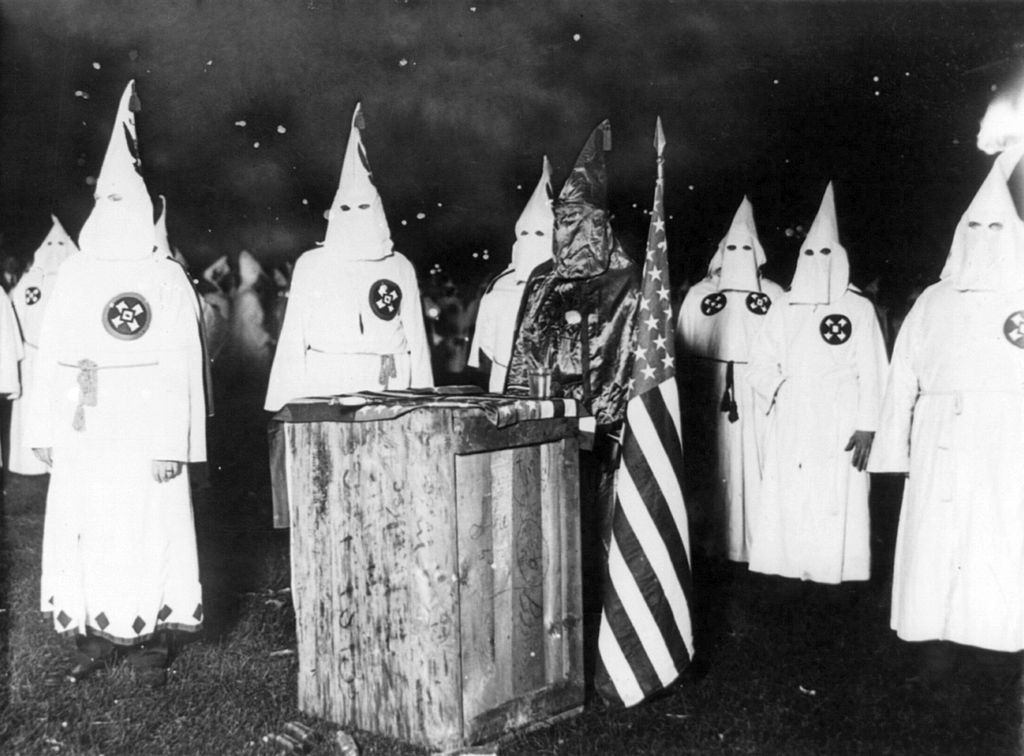

The Ku Klux Klan

After the Civil War, the Ku Klux Klan, led by former Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest, used terrorist tactics to intimidate former slaves. A new version of the Ku Klux Klan arose during the early 1920s. Throughout this time period, immigration, fear of radicalism, and a revolution in morals and manners fanned anxiety in large parts of the country. Roman Catholics, Jews, African Americans, and foreigners were only the most obvious targets of the Klan’s fear-mongering. Bootleggers and divorcees were also targets.

Contributing to the Klan’s growth was a post-war depression in agriculture, the migration of African Americans into northern cities, and a swelling of religious bigotry and nativism in the years after World War I. Klan members considered themselves defenders of Prohibition, traditional morality, and true Americanism.

In 1920, two Atlanta publicists, Edward Clarke, a former Atlanta journalist, and Bessie Tyler, a former madam, took over an organization that had formed to promote World War I fund drives. At that time, the organization had 3,000 members. In three years they built it into a national organization with three million members. After the war, they bolstered membership in the Klan by giving Klansmen part of the ten dollar induction fee of every new member they signed up.

During the early 1920s, the Klan helped elect sixteen U.S. Senators and many Representatives and local officials. By 1924, when the Klan had reached its peak in numbers and influence, it claimed to control twenty-four of the nation’s 48 state legislatures. That year it succeeded in blocking the nomination of Al Smith, a New York Catholic, at the Democratic National Convention.

The three million members of the Klan after World War I were quite open in their activities. Many were small-business owners, independent professionals, clerical workers, and farmers. Members marched in parades, patronized Klan merchants, and voted for Klan-endorsed political candidates. The Klan was particularly strong in the Deep South, Oklahoma, and Indiana. Historians once considered the Ku Klux Klan a group of marginal misfits, rural traditionalists unable to cope with the coming of a modern urban society. But recent scholarship shows that Klan members were a cross-section of native Protestants. Many were women. Many came from urban areas.

The leader of Indiana’s Klan was David Curtis Stephenson, a Texan who had worked as a printer’s apprentice in Oklahoma before becoming a salesman in Indiana. Given control of the Klan in Indiana in 1922 and the right to organize in twenty other states, he soon became a millionaire from the sale of robes and hoods. A crowd estimated at 200,000 attended one Klan gathering in Kokomo, Indiana, in 1923.

A public defender of Prohibition and womanhood, Stephenson was, in private, a heavy drinker and a womanizer. In 1925, he was tried, convicted, and sentenced to life in prison for kidnapping and sexually assaulting 28-year-old Madge Oberholtzer, who ran a state program to combat illiteracy. Stephenson’s downfall, which was followed by the indictment and prosecution of many Klan-supported politicians on corruption charges, led members to abandon the organization in droves. Within a year, the number of Klansmen in Indiana fell from 350,000 to 15,000. By 1930, the Klan had just 45,000 members in the nation as a whole.