The New Woman

The New Woman

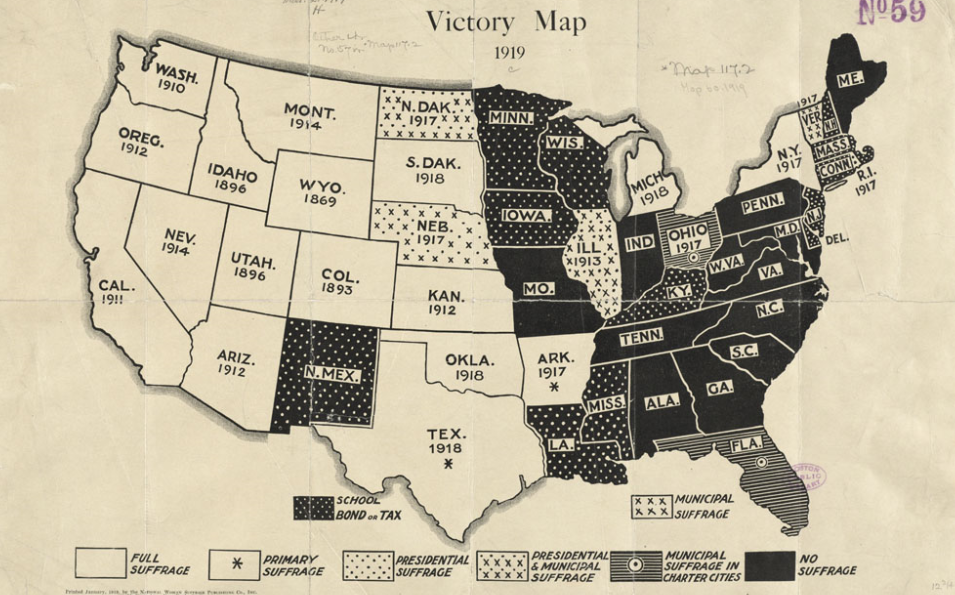

In 1920, after 72 years of struggle, American women received the right to vote. After the Nineteenth Amendment passed, reformers talked about female voters uniting to clean up politics, improve society, and end discrimination.

At first, male politicians moved aggressively to court the women’s vote, passing legislation guaranteeing women’s rights to serve on juries and hold public office. Congress also passed legislation to set up a national system of women’s and infant’s health care clinics, as well as a constitutional amendment prohibiting child labor—a measure supported by many women’s groups.

The early momentum quickly dissipated, however, as the women’s movement divided within and faced growing hostility from without. The major issue that split feminists during the 1920s was a proposed Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution outlawing discrimination based on sex. The issue pitted the interests of professional women against those of working class women, many of whom feared that the amendment would prohibit “protective legislation” that stipulated minimum wages and maximum hours for female workers.

The women’s movement also faced mounting external opposition. During the Red Scare following World War I, the War Department issued the “Spider Web” chart which linked feminist groups to foreign radicalism. Many feminist goals were unachieved in the mid-1920s. Opposition from many Southern states and the Catholic Church defeated the proposed constitutional amendment outlawing child labor. The Supreme Court struck down a minimum wage law for women workers, while Congress failed to fund the system of health care clinics.

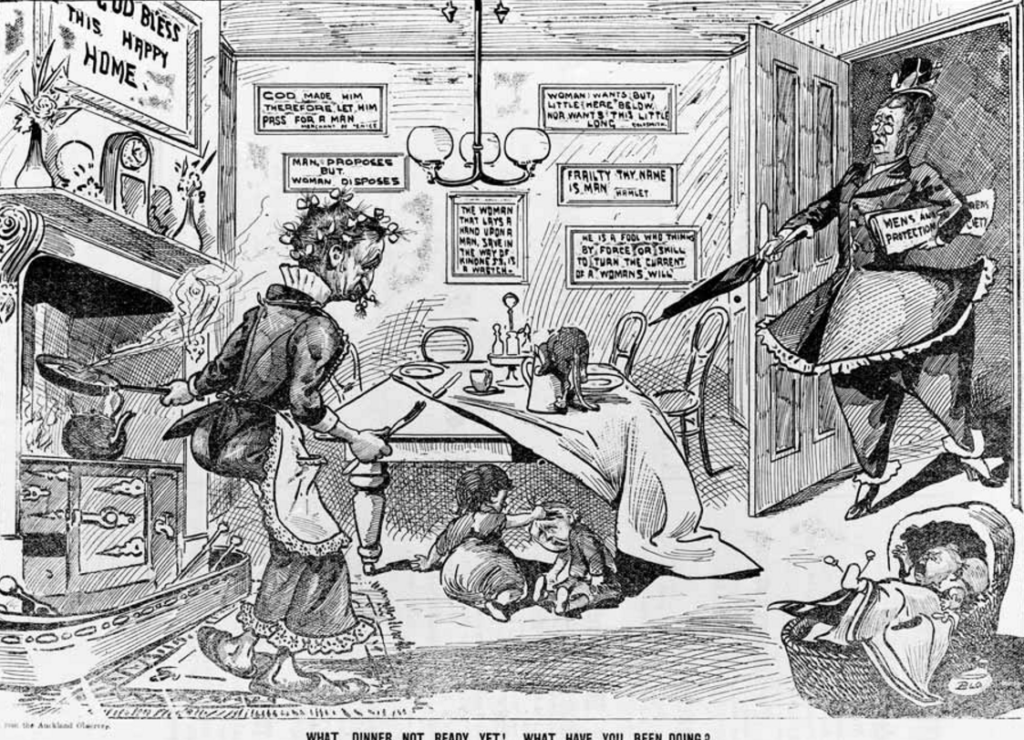

Nor did women did win new opportunities in the workplace. Although the American work force included eight million women in 1920, more than half were black or foreign-born. Domestic service remained the largest occupation, followed by secretaries, typists, and clerks—all low-paying jobs. The American Federation of Labor (AFL) remained openly hostile to women because it did not want females competing for men’s jobs. Female professionals, too, made little progress. They consistently received less pay than their male counterparts. Moreover, they were concentrated in traditionally “female” occupations such as teaching and nursing.

During the 1920s, the organized women’s movement declined in influence, partly due to the rise of the new consumer culture that made the suffragists and settlement house workers of the Progressive era seem old-fashioned. Advertisers tried self-consciously to co-opt many of the themes of pre-World War I feminism, arguing that the modern economy was filled with exciting and liberating opportunities for consumption. To popularize smoking among women, advertisers staged parades down New York’s 5th Avenue, imitating the suffrage marches of the 1910s in which young women carried “torches of freedom”—cigarettes.

Housework

Housework in nineteenth century America was harsh physical labor. Preparing even a simple meal was a time and energy consuming chore. Prior to the twentieth century, cooking was performed on a coal or wood burning stove. Unlike an electric or a gas range, which can be turned on with the flick of a single switch, cast iron and steel stoves were exceptionally difficult to use.

Ashes from an old fire had to be removed. Then, paper and kindling had to be set inside the stove, dampers and flues had to be carefully adjusted, and a fire lit. Since there were no thermostats to regulate the stove’s temperature, a woman had to keep an eye on the contraption all day long. Any time the fire slackened, she had to adjust a flue or add more fuel.

Throughout the day, the stove had to be continually fed with new supplies of coal or wood, an average of fifty pounds a day. At least twice a day, the ash box had to be emptied, a task which required a woman to gather ashes and cinders in a grate and then dump them into a pan below. Altogether, a housewife spent four hours every day sifting ashes, adjusting dampers, lighting fires, carrying coal or wood, and rubbing the stove with thick black wax to keep it from rusting.

It was not enough for a housewife to know how to use a cast iron stove. She also had to know how to prepare unprocessed foods for consumption. Prior to the 1890s, there were few factory prepared foods. Shoppers bought poultry that was still alive and then had to kill and pluck the birds. Fish had to have scales removed. Green coffee had to be roasted and ground. Loaves of sugar had to pounded, flour sifted, nuts shelled, and raisins seeded.

Cleaning was an even more arduous task than cooking. The soot and smoke from coal and wood burning stoves blackened walls and dirtied drapes and carpets. Gas and kerosene lamps left smelly deposits of black soot on furniture and curtains. Each day, the lamp’s glass chimneys had to be wiped and wicks trimmed or replaced. Floors had to scrubbed, rugs beaten, and windows washed. While a small minority of well to do families could afford to hire a cook at $5 a week, a waitress at $3.50 a week, a laundress at $3.50 a week, and a cleaning woman and a choreman for $1.50 a day, in the overwhelming majority of homes, all household tasks had to be performed by a housewife and her daughters.

Housework in nineteenth century America was a full time job. Gro Svendsen, a Norwegian immigrant, was astonished by how hard the typical American housewife had to work. As she wrote her parents in 1862:

We are told that the women of America have much leisure time but I haven’t yet met any woman who thought so! Here the mistress of the house must do all the work that the cook, the maid and the housekeeper would do in an upper class family at home. Moreover, she must do her work as well as these three together do it in Norway.

Before the end of the nineteenth century, when indoor plumbing became common, chores that involved the use of water were particularly demanding. Well-to-do urban families had piped water or a private cistern, but the overwhelming majority of American families got their water from a hydrant, a pump, a well, or a stream located some distance from their house. The mere job of bringing water into the house was exhausting. According to calculations made in 1886, a typical North Carolina housewife had to carry water from a pump or a well or a spring eight to ten times each day. Washing, boiling and rinsing a single load of laundry used about fifty gallons of water. Over the course of a year she walked l48 miles toting water and carried over 36 tons of water.

Homes without running water also lacked the simplest way to dispose garbage: sinks with drains. This meant that women had to remove dirty dishwater, kitchen slops, and, worst of all, the contents of chamber pots from their house by hand.

Laundry was the household chore that nineteenth century housewives detested most. Rachel Haskell, a Nevada housewife, called it “the Herculean task which women all dread” and “the great domestic dread of the household.”

On Sunday evenings, a housewife soaked clothing in tubs of warm water. When she woke up the next morning, she had to scrub the laundry on a rough washboard and rub it with soap made from lye, which severely irritated her hands. Next, she placed the laundry in big vats of boiling water and stirred the clothes about with a long pole to prevent the clothes from developing yellow spots. Then she lifted the clothes out of the vats with a wash stick, rinsed the clothes twice, once in plain water and once with bluing, wrung the clothes out and hung them out to dry. At this point, clothes would be pressed with heavy flatirons and collars would be stiffened with starch.

The last years of the nineteenth century witnessed a revolution in the nature of housework. Beginning in the 1880s, with the invention of the carpet sweeper, a host of new “labor saving” appliances were introduced. These included the electric iron (1903), the electric vacuum cleaner (1907), and the electric toaster (1912). At the same time, the first processed and canned foods appeared. In the 1870s, H.J. Heinz introduced canned pickles and sauerkraut. In the 1880s, Franco American Co. introduced the first canned meals. In the 1890s, Campbell’s sold the first condensed soups. By the 1920s, the urban middle class enjoyed a myriad of new household conveniences, including hot and cold running water, gas stoves, automatic washing machines, refrigerators, and vacuum cleaners.

Yet despite the introduction of electricity, running water, and “labor-saving” household appliances, time spent on housework did not decline. Indeed, the typical full time housewife today spends just as much time on housework as her grandmother or great grandmother. In 1924, a typical housewife spent about 52 hours a week in housework. Half a century later, the average full time housewife devoted 55 hours to housework. A housewife today spends less time cooking and cleaning up after meals, but she spends just as much time as her ancestors on housecleaning and even more time on shopping, household management, laundry, and childcare.

How can this be? The answer lies in a dramatic rise in the standards of cleanliness and childcare expected of a housewife. As early as the 1930s, this change was apparent to a writer in the Ladies Home Journal:

Because we housewives of today have the tools to reach it, we dig every day after the dust that grandmother left to spring cataclysm. If few of us have nine children for a weekly bath, we have two or three for a daily immersion. If our consciences don’t prick us over vacant pie shelves or empty cookie jars, they do over meals in which a vitamin may be omitted or a calorie lacking.