Overview: The 1920s

The 1920s

In 1931, a journalist named Frederick Lewis Allen published an informal history that did more to shape the popular image of the 1920s than any book ever written by a professional historian. The book, Only Yesterday, depicted the 1920s as a cynical, hedonistic interlude between the Great War and the Great Depression—a decade of dissipation, jazz bands, raccoon coats, and bathtub gin. Allen argued that World War I shattered Americans’ faith in reform and moral crusades, leading the younger generation to rebel against traditional taboos while their elders engaged in an orgy of consumption and speculation.

The popular image of the 1920s, as a decade of prosperity, riotous living, and bootleggers and gangsters, flappers and hot jazz, flagpole sitters, and marathon dancers, is indelibly etched in the American psyche. But this image is also profoundly misleading. The 1920s was a decade of deep cultural conflict. The pre-Civil War decades had fundamental conflicts in American society that involved slavery and geographic regions. During the Gilded Age, conflicts centered on ethnicity and social class. Conversely, the conflicts of the 1920s were primarily cultural, pitting a more cosmopolitan, modernist, urban culture against a more provincial, traditionalist, rural culture.

The decade witnessed a titanic struggle between an old and a new America. Immigration, race, alcohol, evolution, gender politics, and sexual morality all became major cultural battlefields during the 1920s. Wets battled drys, religious modernists battled religious fundamentalists, and urban ethnics battled the Ku Klux Klan.

The 1920s was a decade of profound social changes. The most obvious signs of change were the rise of a consumer-oriented economy and of mass entertainment, which helped to bring about a “revolution in morals and manners.” Sexual mores, gender roles, hair styles, and dress all changed profoundly during the 1920s. Young women began to wear more revealing clothing, engage in public smoking, drinking, and dancing, and reject Victorian prudery. Many Americans regarded these changes as liberation from the country’s Victorian past. But for others, morals seemed to be decaying, and the United States seemed to be changing in undesirable ways. The result was a thinly veiled “cultural civil war.”

The Jazz Age

The 1920s was a decade of major cultural conflicts as well as a period when many features of a modern consumer culture took root. In this module, you will learn about the clashes over alcohol, evolution, foreign immigration, and race, and also about the growth of cities, the rise of a consumer culture, and the revolution in morals and manners.

The Postwar Red Scare

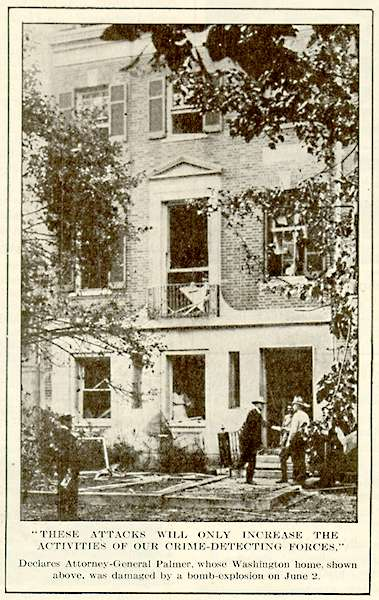

On May 1, 1919 (May Day), postal officials discovered twenty bombs in the mail of prominent capitalists, including John D. Rockefeller and J. P. Morgan, Jr., as well as government officials like Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes. A month later, bombs exploded in eight American cities.

On September 16, 1920, a bomb left in a parked horse-drawn wagon exploded near Wall Street in Manhattan’s financial district, killing thirty people and injuring hundreds. The bomb was suspected to have been the work of alien radicals. Authorities came up with a list of subjects and even questioned the man who had recently reshod the wagon’s horse. But despite the offer of an $80,000 reward, no one was charged with the crime.

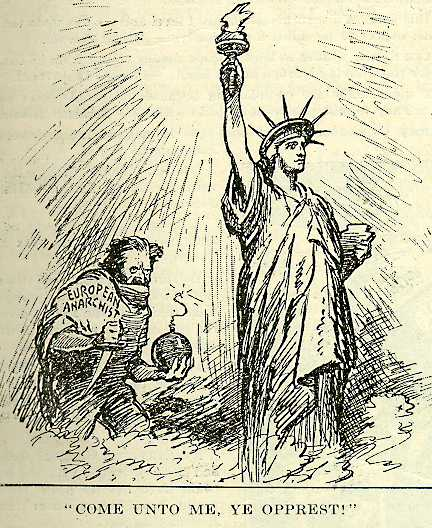

The end of World War I was accompanied by a panic over political radicalism. Fear of bombs, Communism, and labor unrest produced a “Red Scare.” In Hammond, Indiana, a jury took two minutes to acquit the killer of an immigrant who had yelled “To Hell with the United States.” At a victory pageant in Washington, D.C., a sailor shot a man who refused to stand during the playing of the “Star-Spangled Banner”, while the crowd clapped and cheered. A clerk in a Waterbury, Connecticut clothing store was sentenced to jail for six months for remarking to a customer that the Russian revolutionary Lenin was “the brainiest” or “one of the brainiest” world leaders.

In November 1919, in the Washington State lumber town of Centralia, American Legionnaires stormed the office of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Four attackers died in a gunfight before townspeople overpowered the IWW members and took them to jail. A mob broke into the jail, seized one of the IWW members, and hanged him from a railroad bridge. Federal officials subsequently prosecuted 165 IWW leaders, who received sentences of up to twenty-five years in prison.

Congress and state legislatures joined in the attack on radicalism. In May 1919, the House refused to seat Victor Berger, a Socialist from Milwaukee, after he was convicted of sedition. The House again denied him his seat following a special election in December 1919. Not until he was re-elected again in 1922, after the government dropped the sedition charges, did Congress finally seat him. In 1920, the New York State Legislature expelled five members. They were told that they had been elected on a platform “absolutely inimical to the best interests” of New York State.

In 1919 and 1920, President Wilson’s attorney general, A. Mitchell Palmer, led raids on leftist organizations, such as the Communist Party and the radical labor union, the Industrial Workers of the World. Palmer hoped to use the issue of radicalism in his campaign to become president in 1920. He created the precursor to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, which collected the names of thousands of known or suspected Communists.

In November 1919, Palmer ordered government raids that resulted in the arrests of 250 suspected radicals in eleven cities. The Palmer Raids reached their height on January 2, 1920, when government agents made raids in 33 cities. Nationwide, more than 4,000 alleged Communists were arrested and jailed without bond, and 556 aliens were deported—including the radical orator Emma Goldman.

Palmer claimed to be ridding the country of the “moral perverts and hysterical neurasthenic women who abound in communism,” but his tactics alienated many people who viewed them as violations of civil liberties.

Postwar Labor Tensions

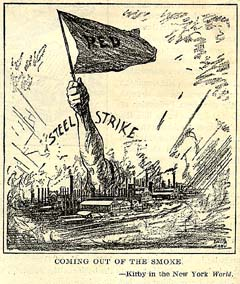

The years immediately following the end of World War I were a period of deep social tensions, aggravated by high wartime inflation. Food prices more than doubled between 1915 and 1920. Clothing costs more than tripled. A steel strike that began in Chicago in 1919 became much more than a simple dispute between labor and management. The Steel Strike of 1919 became the focal point for profound social anxieties, especially fears of Bolshevism.

Organized labor had grown in strength during the course of the war. Many unions won recognition, and the twelve-hour workday was abolished. An eight-hour day was instituted on war contract work, and by 1919, half the country’s workers had a 48-hour work week.

The war’s end, however, was accompanied by labor turmoil, as labor demanded union recognition, shorter hours, and raises exceeding the inflation rate. Over four million workers—one-fifth of the nation’s workforce—participated in strikes in 1919, including 365,000 steelworkers and 400,000 miners. The number of striking workers would not be matched until the Depression year of 1937.

The year began with a general strike in Seattle. Police officers in Boston went on strike, touching off several days of rioting and crime. But the most tumultuous strike took place in the steel industry. About 350,000 steelworkers in 24 separate craft unions went on strike as part of a drive by the American Federation of Labor to unionize the industry. From management’s perspective, the steel strike represented the handiwork of radicals and professional labor agitators. The steel industry’s leaders regarded the strike as a radical conspiracy to get the company to pay a twelve-hour wage for eight hours’ work. At a time when Communists were seizing power in Hungary and were staging a revolt in Germany, and workers in Italy were seizing factories, some industrialists feared that the steel strike was the first step toward overturning the industrial system.

The strike ended with the complete defeat of the unions. From labor’s perspective, the corporations had triumphed through espionage, blacklists, and the denial of freedom of speech and assembly, and through the complete unwillingness to recognize the right of collective bargaining with the workers’ representatives.

During the 1920s, many of labor’s gains during World War I and the Progressive era were rolled back. Membership in labor unions fell from five million to three million. The U.S. Supreme Court outlawed picketing, overturned national child labor laws, and abolished minimum wage laws for women.