The Politics of Reconstruction

The Politics of Reconstruction

The failure of Reconstruction was not inevitable. There were moments of possibility when it seemed imaginable that former slaves might achieve genuine freedom.

Immediately following the war, all-white Southern legislatures enacted “black codes,” designed to force ex-slaves to work on plantations, where they would be put to work in gangs. These codes denied African Americans the right to purchase or even rent land. Vagrancy laws allowed authorities to arrest blacks “in idleness” (including many children) and assign them to a chain gang or auction them off to a planter for as long as a year. The more stringent black codes also barre ex-slaves from owning weapons, marrying whites, and assembling after sunset. Other statutes required blacks to have written proof of employment and barred them from leaving plantations.

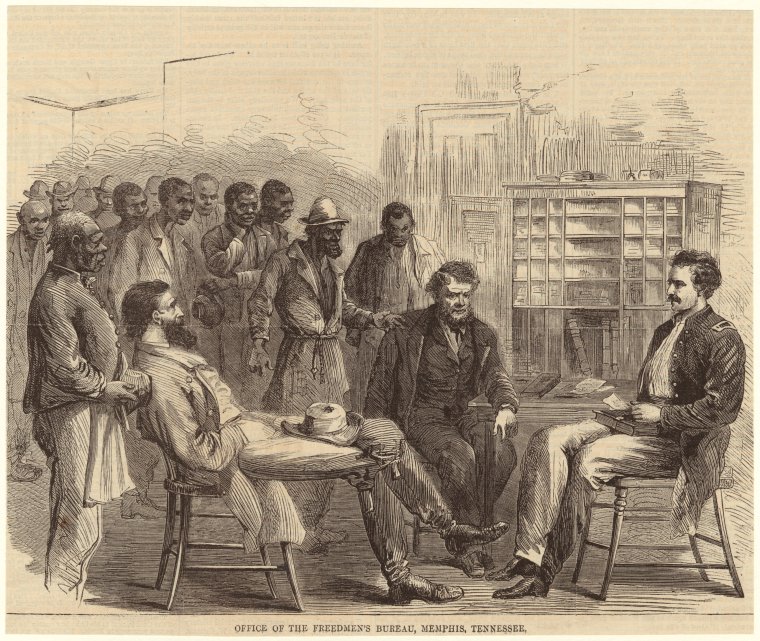

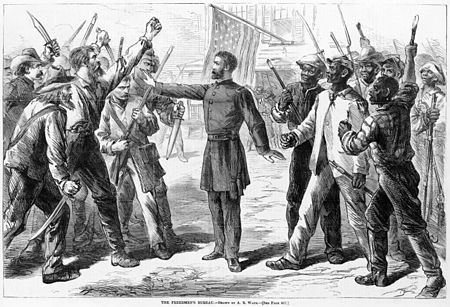

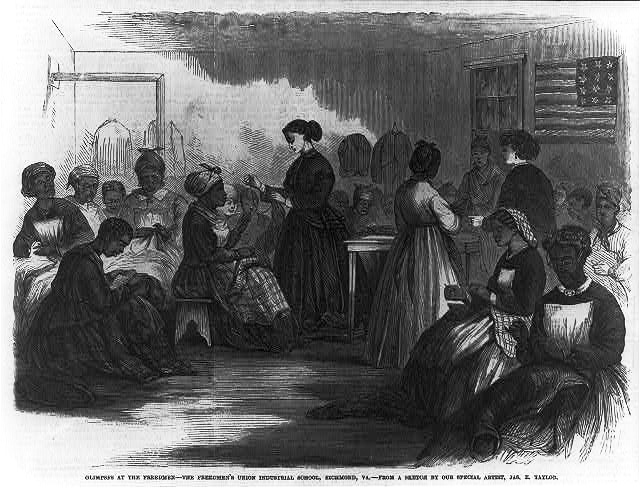

The Freedmen’s Bureau which was established in March 1865 to aid former slaves by providing schools, medical aid, and other services, helped enforce laws against vagrancy and loitering and refused to allow ex-slaves to keep land that they occupied during the war. It ordered freed slaves to sign labor contracts with former masters and other white landowners. In many instances, these contracts did not require the payment of wages. One black army veteran asked rhetorically: “If you call this Freedom, what did you call Slavery?”

Many African Americans in the South defied these efforts to reduce them to virtual re-enslavement by staging strikes and other protests. But lacking land of their own, most ex-slaves were eventually forced to become tenant farmers.

Presidential Reconstruction

After helping to push through the Thirteenth Amendment, abolishing slavery, the President sought to quickly restore the rebel states to the Union. He considered Reconstruction a “restoration” and wanted to readmit former Confederate states after they had repudiated their ordinances of secession, accepted the Thirteenth Amendment, repudiated the Confederate debt, and pledged loyalty to the Union.

President Johnson’s vision of Reconstruction clashed with that of many Republicans. He vetoed a string of Republican-backed measures, including an extension of the Freedmen’s Bureau and the federal government’s first Civil Rights bill in 1865, which declared that all persons born in the United States were now citizens, regardless of race, color, or previous condition. He ordered black families evicted from land on which they had been settled by the U.S. Army. He acquiesced in the black codes which Southern state governments enacted to reduce former slaves to the status of dependent plantation laborers.

Congressional Reconstruction

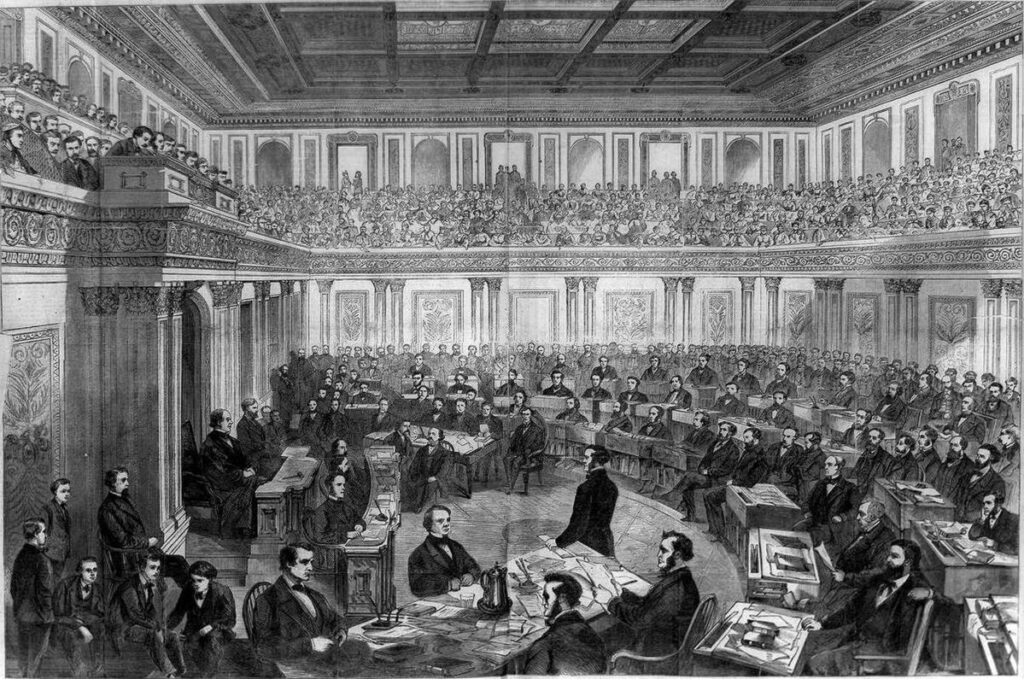

In early 1866, Congressional Republicans, appalled by mass killing of ex-slaves and the adoption of restrictive black codes, seized control of Reconstruction from President Johnson. Congress denied representatives from the former Confederate states their Congressional seats, passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866 over the president’s veto, and wrote the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, extending citizenship rights to African Americans and guaranteeing them equal protection of the laws. The Fourteenth Amendment also reduced representation in Congress of any Southern state that deprived African Americans of the vote. In 1870, the country went even further by ratifying the Fifteenth Amendment, which gave voting rights to black men. In addition, the Fourteenth Amendment established the principle that rights guaranteed by the Bill of Rights applied to state actions. However, the most radical proposals advanced during Reconstruction—to confiscate plantations and redistribute portions to the freemen—were defeated.

In 1867, Congress overrode a presidential veto in order to pass an act that divided the South into military districts that placed the former Confederate states under martial law pending their adoption of constitutions guaranteeing civil liberties to former slaves. The Reconstruction Act of 1867 gave African American men in the South the right to vote three years before ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment.With the vote came representation. Freedmen served in state legislatures. Hiram Revels became the first African American to sit in the U.S. Senate.

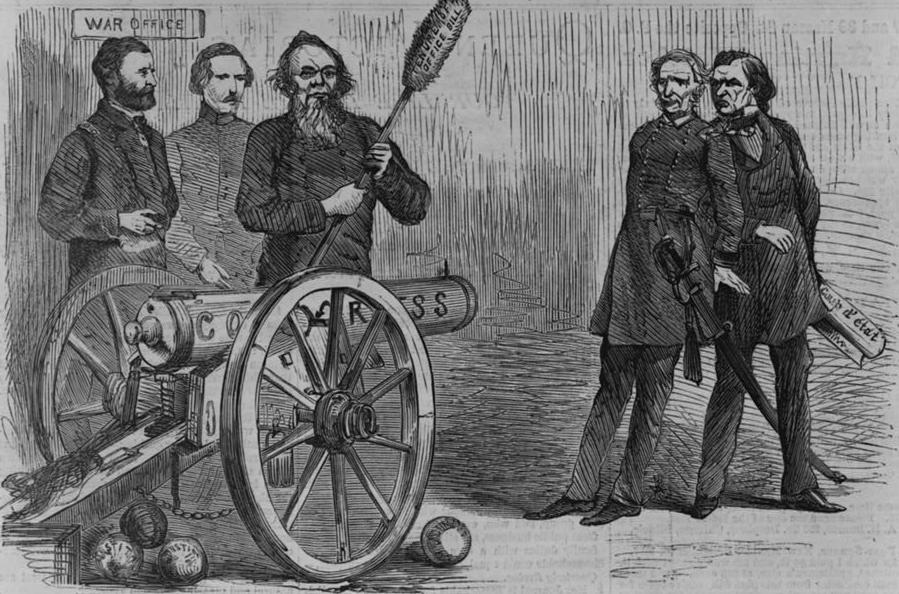

Although the law empowered him to remove recalcitrant Southern officeholders, President Johnson refused. He forbade the Army to try violations of federal law in its courts or to prohibit activities that were not in specific violation of federal or local statutes. Many Republicans regarded the president’s actions as a systematic effort to thwart the will of Congress and to lend aid to enemies of the Union. The hot-tempered Johnson labeled the Republicans scoundrels in the treasonous tradition of Benedict Arnold.

To prevent the president from obstructing its Reconstruction program, Congress passed several laws restricting presidential powers. These laws prevented him from appointing Supreme Court justices and restricted his authority over the Army. The Tenure of Office Act barred him from removing, without Senate approval, officeholders, who had been appointed with the advice and consent of the Senate.

In August 1867, Johnson tested the Tenure of Office Act by removing Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. This act prompted Republicans in Congress to seek to impeach and remove the president.

The Impeachment of President Johnson

In Tennessee Johnson, a 1940s movie about the nation’s first presidential impeachment trial, President Johnson (played by Van Heflin) storms into the Senate chamber and gives an eloquent speech to avert his ouster. In fact, the president’s own lawyers kept him out of the Senate chamber, fearing he would lose his temper.

Officially, Johnson was impeached for violating the Tenure of Office Act, which had been passed over Johnson’s veto, which prohibited the president from dismissing certain federal officials without Senate approval, and for denouncing Congress as unfit to legislate. But those reasons masked the issues that were more important to Congressional Republicans. Johnson had vetoed twenty Reconstruction bills and had urged Southern legislatures to reject the 14th Amendment, guaranteeing equal protection of the laws. He had ordered African American families evicted from land on which they had been settled by the U.S. Army.

Johnson’s lawyers sought to portray the dispute as a partisan attack made to look like a legal proceeding. His opponents insisted he had abused his powers and flouted the will of Congress. The House voted 126-47 to impeach Johnson on eleven separate articles. The proceedings were intensively partisan. One Republican Representative even suggested that Johnson, as vice president, had been involved in the plot to assassinate President Lincoln, just so he could succeed him. The chief of the Secret Service gave false reports that the president had an affair with a woman seeking to obtain pardons for former Confederates.

Johnson’s attorneys argued the Tenure of Office Act applied to officials appointed by the president, and since Secretary of War Stanton was appointed by Lincoln, not Johnson, he was not covered by the act.

The final vote was 35 to 19, one short of the two-thirds needed for conviction and removal from office. Seven Republicans voted to acquit. The Senate voted on two more articles of impeachment, each again just one vote shy of conviction. The chamber never voted on the remaining eight impeachment articles. But Johnson had been defanged. In the future, he no longer obstructed Congress’ Reconstruction policies.

President Johnson spent the rest of his life seeking vindication. He actively pursued the 1868 Democratic presidential nomination but in the end lost the nomination to New York Governor Horatio Seymour, who subsequently lost the election to Republican candidate Ulysses S. Grant. Johnson, then moved back to Tennessee, where he ran unsuccessfully for the U.S. Senate in 1869 and the House in 1872. He was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1874 and was greeted by the Senators with thunderous applause, his desk strewn with roses. After a few months, however, he suffered a series of strokes and died. His wife placed a copy of the U.S. Constitution under his head in his coffin.

Podcast

“Should Andrew Johnson Have Been Impeached”

Listen to the following podcast.

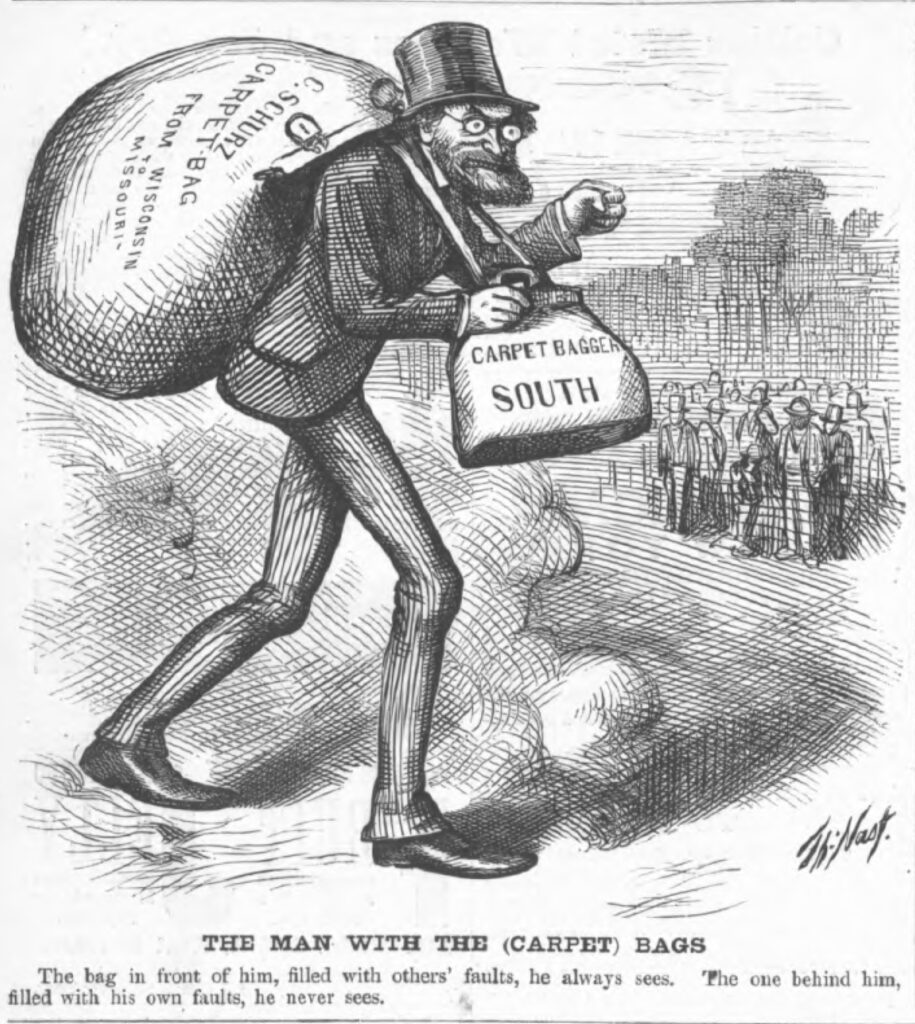

Southern White Republicans

In an event without historical precedent, former slaves joined with white Republicans to govern much of the South. The freedmen, in alliance with carpetbaggers (Northerners who had migrated South during or after the Civil War) and Southern white Republicans derogatorily called scalawags, temporarily gained power in every Confederate state except Virginia. Altogether, over 600 African Americans served as legislators in Reconstruction governments (though blacks comprised a majority only in the lower house of South Carolina’s legislature).

The Republican governments were damned for their extravagance, but they gave the South its first public school systems, asylums, and roads. Southern Republicans sought to modernize the South by building railroads and providing free public education and other social services. The Reconstruction governments drew up democratic state constitutions, expanded women’s rights, provided debt relief, and established the South’s first state-funded schools. Before Reconstruction, there were no statewide, tax supported education systems in the South, except in Tennessee. Freedmen’s academies set up by Northerner philanthropists to educate former slaves provided the framework for state education systems. Meanwhile, the first institutions of higher education for blacks were established in the South. Black colleges founded during Reconstruction included Fisk University in Nashville in 1866, Howard University in Washington in 1867, and Virginia’s Hampton Institute in 1868.

To be sure, some of the Reconstruction governments were plagued by inexperienced and incompetent leadership and corruption, which disillusioned many Northerners. There were a number of examples of flagrant corruption, including one instance in which a state legislature awarded a thousand dollars to a member to cover a lost bet on a horse race. In another example, a New York publisher gave a $30,000 loan to a Georgia official to convince him to adopt a textbook. Nevertheless, the nation’s first integrated governments had many substantial achievements

On average, however, the South’s bi-racial Republican state governments lasted just four-and-a-half years. During the 1870s, internal divisions within the Republican Party, white terror, and Northern apathy allowed Southern white Democrats to return to power.

Re-imagining Reconstruction

Imagine a general from Maine becoming governor of Mississippi in the wake of the Civil War. Or natives of Massachusetts and Illinois serving as governors of South Carolina and Louisiana, respectively.

These things actually happened. Even more strikingly, over 1,500 African Americans held public office during Reconstruction. Two served as U.S. Senators, fourteen served in the House of Representatives, six served as lieutenant governors, and over 600 served in state legislatures. One temporarily became Louisiana’s governor.

But following Reconstruction, no other African American would serve in the U.S. Senate until 1967.

Could things have turned out differently?

Many have speculated that if African Americans had been given land following the Civil War, this might have provided the economic independence necessary to protect their civil rights.

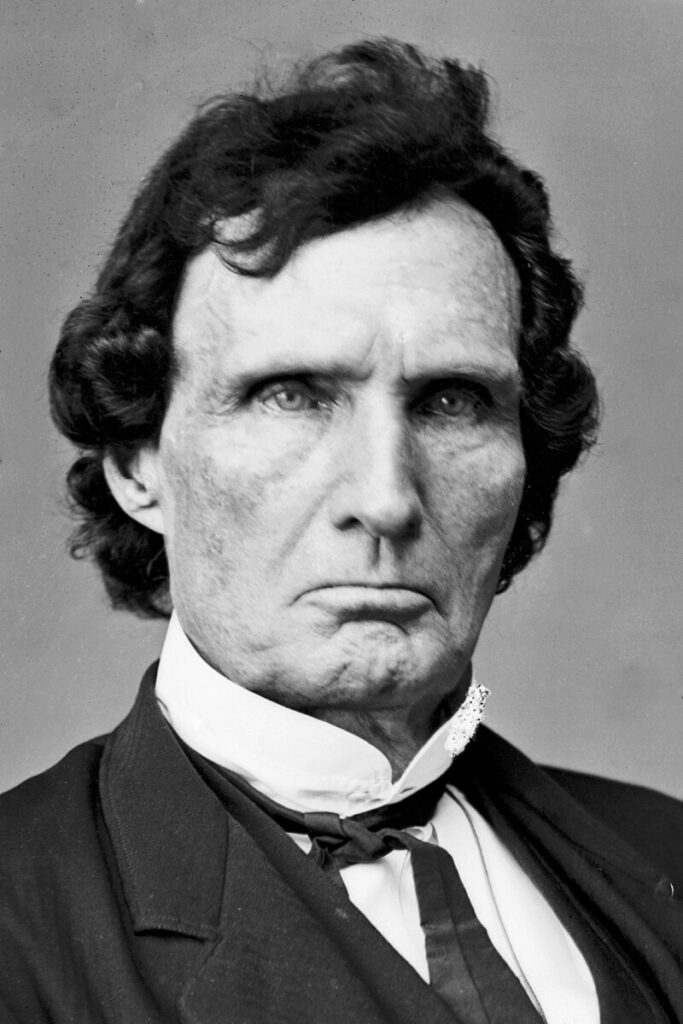

There was such a proposal. In 1867, Thaddeus Stevens, a representative from Pennsylvania, proposed confiscating over 394 million acres of the South’s 465 million acres and redistributing one tenth of that to provide each adult male freedman with 40 acres. The remaining nine-tenths would be sold to the highest bidders, with the proceeds used to pay pensions to Union veterans and discharge three-quarters of the national debt. The bill was defeated. But would it have made a fundamental difference?

At the same time, the same Congress enacted the Homestead Act, which was to distribute over half the nation’s land. In fact, homesteaders in the West got just a quarter of the land. Railroads got four times as much land as homesteaders and the railroads and speculators got the very best land. Congress did pass a Southern Homestead Act opening public land in five states to freedmen, but only a small number of African Americans were able to get lands before Congress reversed itself and offered the land to speculators.

There remains another comparison. Native Americans were promised land in the West that would not be encroached upon by whites. But much of the land that they received was unsuitable for agriculture and much was later taken away. When Native Americans resisted, such resistance was suppressed violently.

Carpetbaggers and Scalawags

According to myth, unscrupulous carpetbaggers from the Northern and unprincipled scalawags from the South manipulated the freedmen to gain control of the state governments. Backed by the presence of federal troops, they embarked on an orgy of corruption, humiliating and impoverishing the helpless South and unsettling relations between blacks and whites. At last, the myth continues, the nation grew weary of the corruption and the cost of maintaining troops in the South. The Army was withdrawn and the responsible white citizenry regained control of their governments.

According to this stereotype popularized after Reconstruction, the carpetbaggers were dishonest fortune seekers whose possession could be put in a satchel. “They are fellows who crawled down South on the track of our armies…stealing and plundering,” said editor Horace Greeley.

Contrary to legend, however, most carpetbaggers were not impoverished opportunists seeking easy money in the South. Rather they were former soldiers who migrated to the South to seek a livelihood. They generated hostility because they supported the Republican Party and defended the civil and political rights of freedmen.

Historical Facts & Fiction

Myths and Realities of Reconstruction

Did the Northern subjected the South to “bayonet rule”?

No. By 1866, there were no more than 15,000 soldiers left in the South, mostly in Texas, fighting Native Americans.

Did Carpetbaggers and Scalawags exploit the South after the Civil War?

No. There was only one Southern state legislature that ever had a majority of blacks and Carpetbaggers. Most Northerners who went South were already there in 1865 or 1866 prior to the establishment of Congressional Reconstruction.

Was the appeal of the Ku Klux Klan confined to poor and uneducated whites?

No. Most of the leaders of the Ku Klux Klan were very respectable members of their communities, business leaders, farmers, and ministers.

Did the Reconstruction era South see an “Orgy of Corruption”?

No, at least not by the standards of the time. To restore the Southern economy, the South invested large sums in railroads—as well as on schools and other public services. Many of the railroad investments failed.