Emancipation

The Day of Jubilee

The North’s victory in the Civil War produced a social revolution in the South. Four million slaves were freed and a quarter million Southern whites had died, one fifth of the male population. $2.5 billion worth of property had been lost.

Slave emancipation did not come in a single moment. In coastal South Carolina and parts of Louisiana and Florida, some slaves gained their freedom as early as the fall of 1861, when Union generals like John C. Fremont, without presidential or Congressional authorization, proclaimed slaves in their conquered districts to be free. During the war, slaves, by the tens of thousands, abandoned their plantations and flocked to Union lines. Black soldiers in the Union Army and their families gained freedom automatically.

Slaves in Texas did not hear about freedom formally until June 19, 1865, which is why “Juneteenth” continues to be celebrated as Emancipation Day throughout the Southwest. Enslaved African Americans in the border states that remained in the Union—Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri—were not freed until December 1865, eight months after the end of the Civil War, when the Thirteenth Amendment, abolishing slavery, was ratified.

For former slaves, emancipation was a moment of exhilaration, fear, and uncertainty. While some greeted the announcement of freedom with jubilation, others reacted with stunned silence. Responses to the news of emancipation ranged from exhilaration and celebration to incredulity and fear.

In Choctaw County, Mississippi, former slaves whipped a planter named Nat Best to retaliate for his cruelties. In Richmond, Virginia, some 1,500 ex-slaves gathered in the Free African church to sing hymns. A parade in Charleston attracted 10,000 spectators and featured a black-draped coffin bearing the words “Slavery is Dead.” A Northern journalist met an ex-slave in Northern Carolina who walked 600 miles searching for his wife and children who had been sold four years earlier. But many freed men and women felt a deep uncertainty about their status and rights.

Ex-slaves expressed their newly-won freedom in diverse ways. Many couples, forbidden to marry during slavery, took the opportunity to formalize their unions. Others, who had lived apart from their families on separate plantations, were finally free to reside with their spouses and children. As an expression of their freedom, freedmen dropped their slave names, adopted new surnames, and insisted on being addressed as “mister” or “misses.” Black women withdrew from field labor to care for their families.

Former slaves left farms and plantations for towns and cities “where freedom was free-er.” Across the South, former slaves left white-dominated churches and formed independent black congregations, founded schools, and set up mutual aid societies. They also held freedmen’s conventions to air grievances, to discuss pressing issues, and to press for equal civil and political rights.

Shocked at seeing former slaves transformed into free women and men, some Southern whites complained of “betrayal” and “ingratitude” when freedmen left their plantations. Revealing slave-owners’ capacity for self-deception, one former master complained that “those we loved best, and who loved us best—as we thought—were the first to leave us.”

In many parts of the South, the end of the war was followed by outbursts of white rage. White mobs whipped, clubbed, and murdered ex-slaves. In contrast, the vast majority of former slaves refrained from vengeance against former masters. Instead, they struggled to achieve social and independence by forming separate lodges, newspapers, and political organizations.

Reconstruction was a time of testing, when freedmen probed the boundaries and possibilities of freedom. Every aspect of Southern life was subject to redefinition, from forms of racial etiquette to the systems of labor that would replace slavery.

Thinking Comparatively

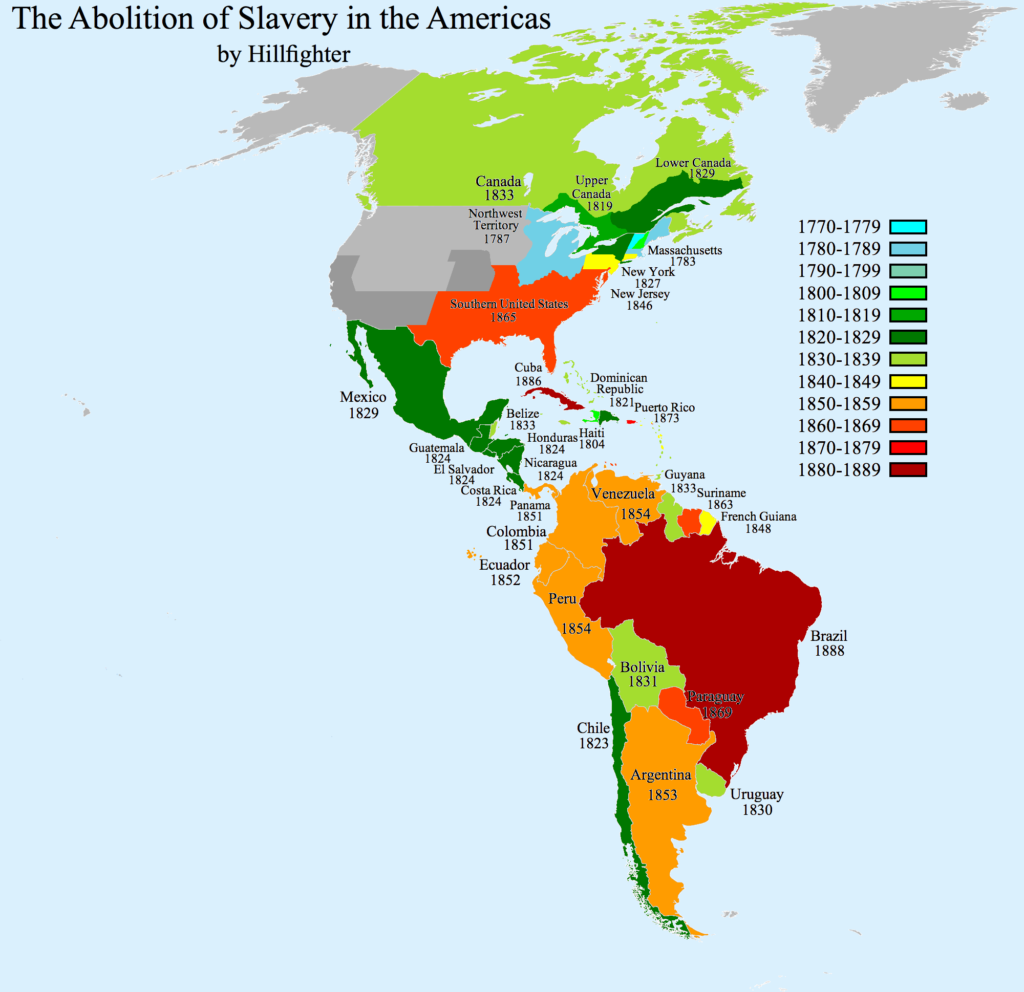

Emancipation in Comparative Perspective

The American South was the only region in the world, except for Haiti, in which slavery was overthrown by the force of arms. It was the only area in which formerly prosperous slave-owners were deprived of the right to hold public office. It was also the only place in which slave-owners received no compensation for the loss of their slave property. Altogether, slave-owners lost $2.5 billion in slave property.

Most important of all, the American South was the only region in which former slaves received civil and political rights, including full citizenship rights as well as the right to vote and to hold elective office. The South was also the only post-emancipation society in which ex-slaves formed successful political alliances with whites.

Yet for all of its uniqueness, Reconstruction in the South ultimately followed many of the same patterns found elsewhere in the Western Hemisphere. In the end, Southern planters managed to hold onto their land, which formed the basis of their economic and political power. By 1877, the Democratic Party, the party of white supremacy, had regained political control over each of the former Confederate states.

Throughout the western hemisphere, the end of slavery was followed by a period of Reconstruction in which race relations were redefined and new systems of labor emerged. In former slave societies throughout the Americas, ex-slaves sought to free themselves from the gang system of labor on plantations and to establish small, self-sufficient farms. Meanwhile, planters and local governments tried to restore the plantation system. The outcome, in almost all former slave societies, was the emergence of a caste system of race relations and a system of involuntary labor such as peonage, debt bondage, apprenticeship, contract labor, tenant farming, and sharecropping.

In every post-emancipation society, the abolition of slavery resulted in acute labor shortages and declining productivity, spurring efforts to restore plantation discipline. Even in Haiti, where black revolution had overthrown slavery, repeated attempts were made to restore the plantation system. On Caribbean islands like Barbados, where land was totally controlled by whites, the plantation system was re-imposed. In other areas like Jamaica, where former slaves were able to squat on unsettled land and set up subsistence farms, staple production fell sharply.

To counteract a sharp decline in sugar production, the British government imported thousands of laborers from Asia into the Caribbean known as “coolies”. To force former slaves to work on plantations, Caribbean governments imposed heavy taxes and enforced strict vagrancy laws.

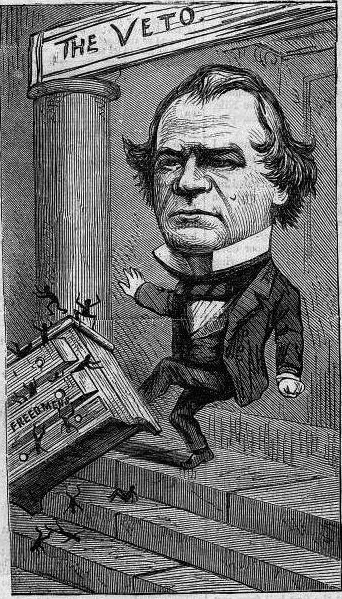

Similar efforts to re-impose forced labor under new names also occurred in the post-Civil War South, but with a crucial difference. Having defeated the Confederacy and emancipated the slaves, Northern Republicans were convinced that securing the peace and protecting the civil rights of former slaves required unprecedented extensions of federal power. A titanic struggle took place between President Andrew Johnson—who permitted the establishment in 1865 of all-white governments that restricted the rights of ex-slaves—and Republicans in Congress who were determined to protect the basic rights of former slaves.

The Republican commitment to free labor would prevent the planters from re-imposing slavery in a new guise. If the freedmen were not reduced to servitude, then many would not become independent landowners either. Instead, landlords and laborers would compromise their differences by adopting a system of sharecropping — a system of tenant farming in which former slaves leased land in exchange for a share of their crops — which would perpetuate Southern poverty for decades.

Reconstruction also had a more positive legacy. It was during this period that African Americans in the South established churches and schools that would provide the institutional basis for later challenges to inequality. And the constitutional amendments ratified during Reconstruction would provide the legal basis for the attack on racial segregation during the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s.

Like an earthquake that shakes the ground and then subsides, Reconstruction came and went. But it did fundamentally alter the nation’s landscape.

Sharecropping

What the freed men and women wanted above all else was land on which they could support their own families. During and immediately after the war, many former slaves established subsistence farms on land that had been abandoned to the Union Army. But President Andrew Johnson, a Democrat and a former slave-owner, restored this land to its former owners. The failure to redistribute land reduced many former slaves to economic dependency on the South’s old planter class and new landowners.

During Reconstruction, former slaves and many small white farmers became trapped in a new system of economic exploitation known as sharecropping. Lacking capital and land of their own, former slaves were forced to work for large landowners. Initially, planters, with the support of the Freedmen’s Bureau, sought to restore gang labor under the supervision of white overseers. But the freedmen, who wanted autonomy and independence, refused to sign contracts that required gang labor. Ultimately, sharecropping emerged as a sort of compromise.

Instead of cultivating land in gangs supervised by overseers, landowners divided plantations into 20 to 50 acre plots suitable for farming by a single family. In exchange for land, a cabin, and supplies, sharecroppers agreed to raise a cash crop (usually cotton) and to give half the crop to their landlord. The high interest rates landlords and sharecroppers charged for goods bought on credit (sometimes as high as 70 percent a year) transformed sharecropping into a system of economic dependency and poverty. The freedmen found that “freedom could make folks proud but it didn’t make ’em rich.”

Nevertheless, the sharecropping system did allow freedmen a degree of freedom and autonomy far greater than they experienced under slavery. As a symbol of their newly won independence, freedmen had teams of mules drag their former slave cabins away from the slave quarters into their own fields. Wives and daughters sharply reduced their labor in the fields and instead devoted more time to childcare and housework. For the first time, black families could divide their time in accordance with their own family priorities.

Evaluating Emancipation

Almost everywhere that slavery was abolished, slavery was replaced with some system of involuntary or forced labor. Sometimes such labor was enforced through violence. At other times, through peonage and debt bondage or laws prohibiting vagrancy.

Even in Haiti, where slaves succeeded in overthrowing slavery by revolution, black leaders forced former slaves into fields under armed black guards.