History Through…

History Through…

…Clothing

Our clothes are costumes that transmit important information about us: our job, social status, taste, and personality. Clothing also shapes our bodies and symbolizes distinctions in social class and outlook.

Clothing is not simply protection against the weather or a way to protect or hide various parts of the body. It also expresses a person’s identity. Clothes can express one’s occupation. Examples include a doctor’s scrubs or a business person’s tailored suit or a priest’s vestments. Or clothes can symbolize a person’s values. Blue jeans can be work pants, but jeans can also express disdain for formality and convention.

Expectations about age, gender, and social class are often expressed through clothes. Clothes that are appropriate at one stage of life might be considered inappropriate for those who are older. Pants, which for a long time were considered inappropriate for women, are now commonly worn by both women and men. For a long time, certain kinds of dress, such as overalls or work shirts, were only considered appropriate for farmers and farm laborers or factory workers

Fashion is not simply decorative. Fashion is also a barometer of social and cultural change.

Contact across geographical and cultural boundaries has had a profound effect on dress. During the eleventh century, the Crusades prompted a craze for eastern textiles across Europe. Robes, veils, embroidery, patterns on textiles, tailored leggings, flowing skirts, and silk and other lightweight fabrics became popular. A carefully crafted hierarchy of fashion, with certain clothing and certain colors (such as purple) appropriate only for those of the highest rank, began to break down.

The vest (or waistcoat), a sleeveless under-coat, was introduced in the 1500s, reflecting Persian and Turkish influences. Cotton cloth and cashmere shawls arrived in the West from India during the eighteenth century; pajamas arrived from the sub-continent in the late nineteenth century.

Some of the most far-reaching changes in dress took place during the Age of Revolution, the period of radical political and societal transformation stretching from the 1770s until 1820. A younger generation abandoned the fashions of its elders. Younger men discarded wigs, stopped powdering their hair and faces, and dumped knee-breeches and calf-length stockings for looser-fitting ankle-length trousers. Young women, inspired by the classical ideals of democratic Greece and Republican Rome, women favored high waisted dresses, a natural figure, and light, flowing gowns.

History Through…

…Hairstyles

Hair can be styled in extraordinarily diverse ways. Think Afro, Beehive, Bob, Bouffant, Caesar, Cornrows, Crewcut, Dreadlocks, Ducktail, Grunge, Mohawk, Mullet, Pageboy, or Pixie. It can be blow dried, braided, colored, cropped, curled, feathered, gelled, knotted, layered, parted, and straightened. It can be worn short, long, or in between, and disheveled, geometric, shaggy, slicked back, spiked upward, or tousled. It can also be greased, highlighted, permed, powdered, sprayed, or treated with gel, mousse, ointments or pomade. The forehead can be covered with bangs or left exposed.

Hair is among humans’ most malleable physical attributes. Humans are the only animals that dye, flatten, plait, shave, or weave their hair. They are also the only animals to wear wigs or hair pieces or extensions. Thus hairstyles are ideal for expressing a person’s public identity.

Hair is much more than a filament growing out of skin follicles. Hair carries important symbolic, cultural, and even political significance. Hair is associated with status, breeding, and identity. Whole lifestyles are symbolized by hair: Hippies, Punk, Rastafari, or Skinhead.

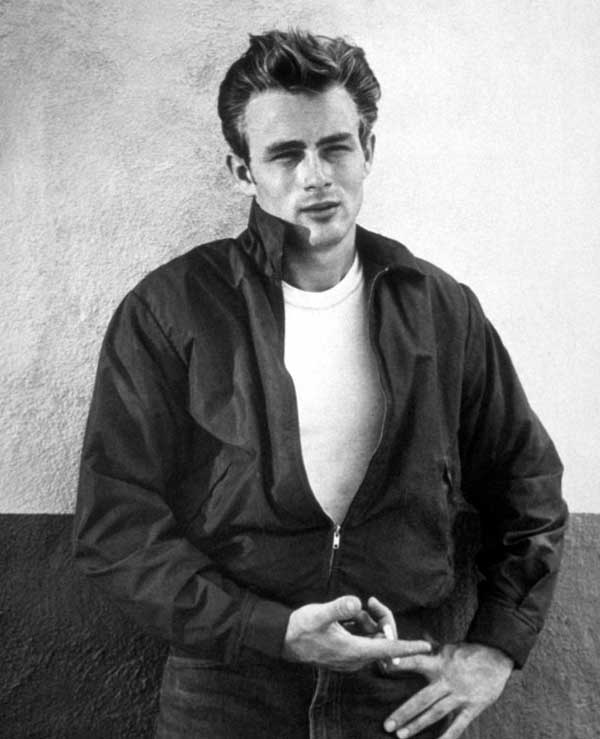

Hair is a powerful symbol of individual and group identity. During the 1950s, duck-billed haircuts became a potent symbol of defiance for white teenage working-class males. In the 1960s, hippies’ long hair signified freedom from social constraints, while the Afro hair style (like West Indian dreadlocks) was a symbol of racial pride and unshaven body hair was a symbol of women’s independence. More recently, punks dyed their hair garish colors while skinheads shaved their heads as symbols of alienation from the dominant culture. The military considers short hair symbolic of discipline.

Hair is also a marker of age. During the nineteenth century, parents did not cut young boys’ hair until they reached the age of five or six. Childhood was associated with asexual innocence, and boys and girls wore their hair similarly. Nineteenth-century girls were expected to raise her hair above her neck, often wrapped in a bun, when she reached her mid-teens. In contemporary American society, long hair among women is generally associated with youth; shorter hair, with age.

In many societies, length of hair has often defined sexual difference, with men’s hair cut shorter than women’s. Indeed, St. Paul said “that if a man has long hair it is a shame unto him… But if a woman has long hair it is a glory to her.” But this gender distinction is certainly not universal. Many women wear their hair short, and short hair can send many contrasting messages. It can be childlike, tomboyish, serious, or rebellious. Wearing one’s hair up can be connected to elegance or conversely to dowdiness. Wearing it down is often considered carefree but also as unprofessional. Following the second world war, French women who collaborated with the Nazis were shorn of their hair as a way to humiliate them.

In a society that values youth, hair loss was, in the 1960s and 1970s, a sign that a man was over the hill. But since the 1980s, many men have shaved their heads as an alternate symbol of masculinity and virility.

Hair length has also been a political statement. Men in England in the 1640s were divided between the roundheads, who had short hair, and cavaliers, with long hair. Through hairstyling, enslaved African Americans were able to assert their cultural autonomy and a distinctive aesthetic sensibility. Many enslaved women styled their hair in distinctive ways, through complex patterns of braiding or weaving objects, including seashells and beads, into their hair. During the 1960s and 1970s, for African Americans to wear their hair “naturally” was to express racial pride.

Hair color, too, has powerful associations. In the twentieth century, a disproportionate number of actresses, models, and female sex symbols had blond hair, which was associated with purity and innocence but also with sexiness, while male sex symbols tended to have dark colored hair. Meanwhile, the hair color gray is associated with aging.

Which hairstyles are considered physically attractive has varied widely over time. Women, at the end of the American and French Revolutions, stopped using high and complicated hairstyles and wore their hair natural, with no powder, held with tortoise shell combs, pins, or ribbons, instead of elaborate ornaments.

History Through…

…Food

Every era has its own distinctive cuisine. Yet what seems laughable today was considered delicious in its time.

Today’s chefs celebrate ingredients that are natural, organic, authentic, and local. Not so, during the 1950s.

As young families flocked to the country’s booming suburbs following World War II, many strove to break free from the ethnic cooking favored by their mothers and grandmothers. Young suburban mothers, who married at around the age of twenty and were raising three, four, or five children born in rapid succession, saved time by preparing many dishes by assembling canned and pre-prepared and frozen ingredients, like tuna noodle casserole or chicken a la king.

World War II had given enormous impetus to the food processing industry, which had to feed the 16 million troops stationed overseas. When the war was over, these companies sought new markets, and using newly developed preservatives, food colorings, artificial flavors, and additives, combined with new techniques for deep freezing and quick canning, reached out to a rapidly expanding consumer market. A plethora of convenience foods suddenly appeared, such as sugared cereals for kids, like Trix, or processed cheese, like Velveeta.

Today, the nutritional quality of many of these processed and prepared foods—laden with salt, sugar, and fat—has been called into question. But at the time, these seemed to symbolize American abundance and progress.

Processed food was something to be celebrated. These included Wonder Bread, a sponge-like, highly processed enriched white bread, Jell-O, a prepared gelatin dessert, Pillsbury refrigerated biscuits, and Miracle Whip, a sweet, mayonnaise-like dressing, seemed more sanitary and modern than dishes prepared from scratch. Sauces might be made from canned soup. Scalloped potatoes might be made from reconstituted potato.

What’s striking in retrospect is how colorful and imaginative many of the dishes were.

There was Fonduloha, a mixture of pineapple, turkey, mayonnaise, curry, peanuts, coconut, and canned mandarins, put back into a pineapple shell.

Cuteness was valued. Dinners featured pearl onions, button mushrooms, and cherry tomatoes. Many of the dishes were whimsical: Cookies were molded into various shapes, food coloring was added to icings and cakes, and Rice Krispy treats combined marshmallows with the rice cereal. There were popular dishes like polka-dotted macaroni and cheese. A box of the electric orange sticky pasta, which included artificial preservatives and synthetic colors, was combined with hot dogs.

Families could not yet count on a wide variety of fresh fish or fruits and vegetables year round. Foods we take for granted today, like fresh asparagus, were available for very limited seasons. As a result, there was a greater reliance on items like canned peaches or fruit cocktail.

People ate at restaurants less and prepared dishes that were meant to look fancy and festive. One example was Cherry Pineapple Bologna, consisting of instant mashed potatoes, bologna glazed with crushed pineapple and maraschino cherry, dyed extra red with food coloring.

Adults entertained at home much more than they do today and the presentation of the food was important. For the first time, couples with relatively modest incomes could afford to host dinner parties, with appetizers prepared from frozen cocktail franks or cheese balls, and desserts meant to be spectacular, liked Baked Alaska or Jell-O molds.

In retrospect, one is especially struck by the absence of “exotic” foods. Bagels, egg rolls, and tacos, let alone curries, were not yet part of mainstream diets. Pizza had only been introduced into wide circulation as a result of the second world war. Spaghetti was commonly served with a sauce made from ketchup.

In recent years, the American diet has grown much more diverse, partly as a byproduct of immigration. Some foods, including bagels, egg rolls, and tacos, are widely embraced by the mainstream culture, but other foods, such as knishes (dough that is baked or fried and is typically filled with mashed potato, ground meat, sauerkraut, onions, and buckwheat), or menudo (a spicy tripe soup), or ris de veau (sweetbreads, or calf’s pancreas), are not.

History Through…

…Holidays: Halloween

Masks, costumes, trick-or-treating, haunted houses, black cats, spiders, cobwebs, ghouls, ghosts, and bobbing for apples—these are the symbols of Halloween, this country’s most popular (if also the most contentious) secular holiday and the largest seasonal marketing event outside of Christmas.

Halloween takes place at the boundary between fall and winter. Symbolically, it crosses the divide between superstition and rationality, life and death, and the everyday world and the supernatural.

Popular histories trace its roots back to pre-Christian pagan traditions, but the American Halloween has its roots in an odd mixture of religious and folk traditions. The word comes from a Christian holiday, All Hallows’ Eve. This is the evening before All Hallows’ Day, a day to honor the Saints and the deceased and pray for those in purgatory, where the souls of sinners expiate their sins before entering heaven. Thus, it was a day to commune with the spirits of the dead.

Halloween also falls near Guy Fawkes Night, an annual English celebration held on November 5th, marking the anniversary of the discovery of a plot to blow up the Houses of Parliament in 1605. It is commemorated with bonfires and fireworks. Halloween, in short, was a hodgepodge of various traditions, taking on aspects of May Day, Midsummer’s Night, Guy Fawkes Night, and All Hallows’ Eve. By the early nineteenth century, it had become an occasion for transgression. It was a night for vandalism and rowdiness. Especially between 1880 to 1920, many young men seized on Halloween as an opportunity for rioting and rowdiness.But Halloween also had roots in superstitions that have persisted over hundreds of years as well as in the folk traditions brought by Scottish and Irish immigrants. These immigrants carried with them traditions of autumn revels and ghost lore.

It was only in the late 1930s that Halloween’s rowdiness was tamed, and October 31st was transformed into a children’s holiday. As the country slowly emerged out of the Great Depression, there was a growing desire to celebrate childhood innocence. Halloween offered an occasion for children to disguise themselves by donning costumes, pretend to be adults, wrestle with artificial terrors, and demand treats from their neighbors. Costumes and trick-or-treating became Halloween’s defining features.

It did not take long for Halloween to become highly commercialized. During the 1930s, a theatrical-costume maker named Ben Cooper, whose business was suffering from the Depression, struck a deal with the Walt Disney Company to produce costumes based on Disney characters. In the 1960s, his company began to make costumes of superheroes like Spider-Man and Batman and in the 1970s, of characters from Star Trek and Star Wars in the ’70s. Cooper’s example would inspire others to make costumes not only of ghosts and goblins, but of television characters and movie stars.

Haunted houses, designed to terrify visitors, have now become commonplace. But the first, Disneyland’s Haunted Mansion, only opened in 1963.

Today, Halloween scares up big profits for candy makers and costume manufacturers, with $2.6 billion annually in candy sales and nearly $2 billion in costume sales.

In recent years, Halloween has been partly reclaimed by adults. Gays and lesbians were among the first to seize on Halloween as an occasion for costumed revelry, merriment, and parties. This example has been embraced by many twenty-somethings.

To a historian, two aspects of Halloween raise interesting questions. One is why this society, which has great difficulty dealing with the realities of death and dying, has a holiday that fixates on skeletons, ghosts, and haunted houses.

To be sure, some groups have formal rituals to acknowledge mortality or recall the departed. Each year, on Día de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead, Mexican Americans pay homage to deceased loved ones with processions, vigils, and the creation of altars at home or graves, featuring candles and cutouts called papel picado. Jewish Americans light Yahrzeit candles on the anniversary of a loved one’s death.

Yet while violent death pervades American popular culture, this society has few rituals to remember the dead. Graveyards, once located in the very center of towns, are now relegated to the outskirts. Compared to earlier customs, today’s funeral practices are much simpler and more austere. Rarely are the dead entombed in elaborate memorials. The elaborate ceremonies that marked nineteenth century funerals—when horse-drawn hearses carried the black crepe-covered caskets—have disappeared. Our very language—with phrases liked “pass on”—evades the finality of death.

Yet zombies, ghosts, and tombstones remain central to Halloween.

A second issue that Halloween raises is why a society and that emphasizes rationality and level-headedness has an evening that centers on witches and demons. A little over three centuries ago, American colonists executed witches, but today, in stark contrast, witchcraft and goblins provide an opportunity for parties.

History Through…

…Names

The English colonists who first arrived in what is now the United States drew their names from a very small pool. About half of all boys in the late sixteenth-century “Lost Colony” of Roanoke Island were named John, Thomas or William, and more than half of newborn girls in the Massachusetts Bay Colony were named Mary, Elizabeth or Sarah. It was also common for New Englanders to give girls names that resonated with Puritan religious values, such as Charity and Patience.

Toward the end of the seventeenth century, greater diversity in names appeared as growing numbers of German, Scottish, and Scot-Irish immigrants arrived. German immigrants introduced such names as Frederick, Johann, Matthias, Barbara, and Veronica, while the Scot-Irish brought such names as James, Andrew, Alexander, Archibald and Patrick. Gaelic names including Duncan, Donald and Kenneth also appeared, while the Welsh contributed Hugh, Owen and David.

By the late eighteenth century, girls began to receive classical names such as Lucretia, Cynthia, and Lavinia, and more parents gave their children middle names. Less formal names also appeared, including Nancy, Sally, and Betsy. The final decades of the eighteenth century also witnessed the revival of old Anglo-Saxon names such as Alfred, Egbert, Harold, and Edmund and Edith, Ethel and Audrey. This effort to evoke the distant past was an expression of a cultural movement known as Romanticism.

Naming practices offer a window into how values and tastes have shifted over time. The historical record offers a particularly rich source of insights into why certain names grow in popularity while others go out of style. It is striking that many of today’s most popular children’s names, especially girls’ names, were virtually unknown just half a century ago. Some popular names fell out of favor, like Lisa or Beth, while others, including Jayden, Justin, and Jason for boys, and Mia or Maya, Kayla, and Madison among girls, became much more common.

Certain long-term trends in naming patterns stand out. Fewer parents today name a first-born child for a father or mother. Fathers’ influence on children’s names appears to have waned, with many fathers ceding the choice of a first name to the mother in exchange for using his last name. Today’s parents appear to spend more time musing over a child’s name than parents in the past. The most striking trend in recent years has been a heightened emphasis on individuality, originality, and adventurousness in names.

Names tied to a particular era—like Barbara, Nancy, Karen, or Susan—or ethnic groups—like Giuseppe and Helga—have declined in popularity, although Biblical and antique names (like Abigail, Hannah, Caleb, and Oliver) have grown in frequency as have names associated with defunct occupations (like Cooper, Carter, and Mason).

In the past, there were particularly marked regional differences in naming patterns, with antebellum white Southern males especially likely to use surnames or ancestral names as first names (such as Ambrose, Ashley, Braxton, Jubal, Kirby, or Porter), reflecting an emphasis on family honor. The parents of baby boomers were especially likely to give their children informal names (like Tom or Jeff or Judy) or diminutives (like Stevie or Tommy or Suzy), and to confine their names to a relatively small pool of conventional options, while their children often gave more formal, exotic, or idiosyncratic names (such as Jonathan instead of John or Elizabeth instead of Beth) to their offspring.

Semantic associations and sound preferences appear to have a strong impact on the names parents bestow on their children. In recent years, there has been a tendency to adopt names that begin with a hard “k” (as opposed to baby boomer names that often ended with a “k,” like Frank, Jack, Mark, or Rock), or end with “-er” or “-a”, while girls’ names that end with “-ly” (like Emily) have declined in frequency.

Place names, like Georgia, have grown more common, while girls’ names associated with flowers or decoration (like Violet), have declined as have names that seem old fashioned (like Gladys).

Names are signals that send out messages, and parents today seek to emphasize their child’s individuality and to give them names that will seem appropriate when they enter adulthood.

There is a tendency among the general public to assume that mass media have a particularly great impact on naming practices, but it does not appear to be the case that the names of public figures, entertainers, celebrities, or characters in television shows or movies exert an outsized influence. However, negative associations (with scandal or a reviled or comic figure (Adolf Hitler or Donald Duck) do affect names’ popularity. Social movements, especially feminism, have had an impact on naming, with girls now more likely to receive cross-gender or androgynous names.

The relationship between ethnicity and social class and naming patterns is complex. Curiously, religious names came into fashion at precisely the time that church attendance was dropping, and parents who were most active religiously were the least likely to give their children Old Testament names. Today, fewer practicing Catholics name their children after saints. Some ethnic groups, notably Irish Americans, tend to draw upon names with a clear ethnic identification (such as Megan, Kelly, Caitlin, or Erin), while other groups, such as Italian Americans, do not. Currently, it is common among Mexican Americans to adopt girls’ names that end with an “–a” or names that have both traditional and Anglo counterparts (like Angela), while among boys’ certain names with clear ethnic connotations, like Jose or Jesus have declined, while others, like Carlos, have grown more common. Meanwhile, highly educated mothers are more likely to give daughters names that connote strength and substance (such as Elizabeth or Catherine).

History Through…

…Language

Each generation coins its own distinctive words. The 1920s brought “attaboy,” “bootleg,” and “skedaddle.” World War II brought us “swell” and “gung ho.” The 1960s popularized “cool,” “groovy,” and “psychedelic.” The 1970s and 1980s brought “slacker” and “grunge.”

As conditions of life shift, so does the vocabulary. Some new words are technology-driven, like “networking” or “selfie.” Some result from shifts in demography, like “blended family,” which arose as rates of divorce and remarriage became increasingly common.

Hoodlum

We know what a “hoodlum” is—a young ruffian. But where did the word come from? From San Francisco in the late nineteenth century. The word first appeared in English in 1871.

At that time, youth gangs in San Francisco repeatedly attacked Chinese immigrants, throwing bricks at them and beating them.

An 1875 article in Scribner’s Magazine described the gangs of young white men this way: “The Hoodlum is a distinctive San Francisco product. …He drinks, gambles, steals, runs after lewd women, and sets buildings on fire. One of his chief diversions, when he is in a more pleasant mood, is stoning Chinaman. That the Hoodlum appeared only three or four years ago is somewhat alarming.”

Anti-Chinese violence reached a peak in 1877, when anti-Chinese rioting left four immigrants dead and destroyed $100,000 worth of property. Five years later, the U.S. Congress enacted the first law restricting immigration, The Chinese Exclusion Act. Wrote the New York Times: “The plain truth is that a violent and discourteous act was demanded by the hoodlum sentiment of the Pacific coast, and this demand has been listened to.”

Hipster

What’s a hipster? An affluent young bohemian who lives in gentrifying neighborhoods and who is caught up in the latest fashion and culture trends. The word comes from hip, that is, cool and trendy.

Hipsters seemed to appear out of nowhere during the 1990s.

Where did the word come from? From jazz during the 1930s. Jazz generated its own lingo or jive. There were words like hip cat, daddy-o, baby, beat (exhausted), blow your top, boogie woogie, bread (money), bug (to annoy), chick (young woman), clinker (something fluffed), dig (understand), drag (boring), gig (a job), groovy, pad (apartment), and split (leave).

Racism

The first recorded use of the word racism was by a man named Richard Henry Pratt in 1902. Pratt wrote this: “Segregating any class or race of people apart from the rest of the people kills the progress of the segregated people or makes their growth very slow. Association of races and classes is necessary to destroy racism and classism.”

Today, Pratt is best known for a phrase: “Kill the Indian and save the man.”

Here’s exactly what Pratt said: “A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one,” Pratt said. “In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead.

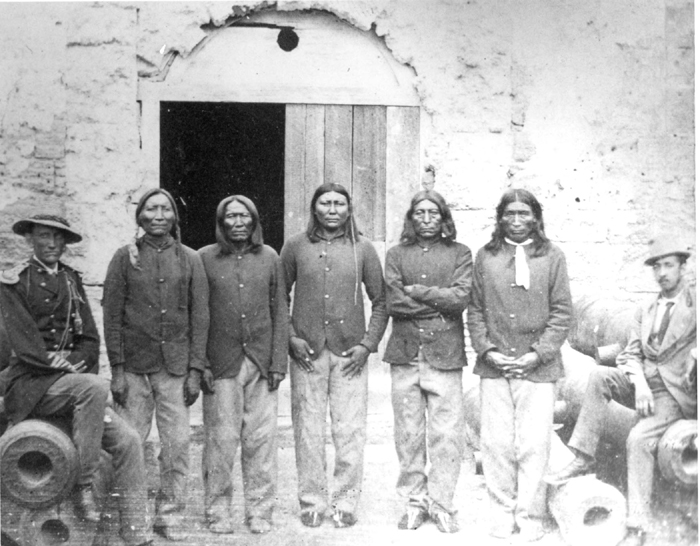

At the time, Pratt was considered a humanitarian who wanted to solve the nation’s “Indian problem.” He feared that Indians would die out and he thought the best way to save Indians was through assimilation and education. Congress gave him an abandoned military post in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, to set up a boarding school for Native children. The government withheld rations from families which refused to send their children to the boarding school.

The Carlisle school sought to totally erase Indian culture. Students were forbidden from speaking Indian languages or from practicing Indian religions. School administrators cut students’ hair and forced them to dress like whites.

At the school, beatings were commonplace and tuberculosis ran rampant.

So we might ask, was Pratt himself a racist?