The End of Reconstruction

Redemption

More than any other Southern city, New Orleans, Louisiana, tested the boundaries of possibility during Reconstruction. With the largest black population of any city in the nation, New Orleans was the first city in the South to integrate its police force and to experiment with school integration. At least 240 blacks in New Orleans were active in Reconstruction politics, and three served as Louisiana’s lieutenant governor and one served briefly as acting governor.

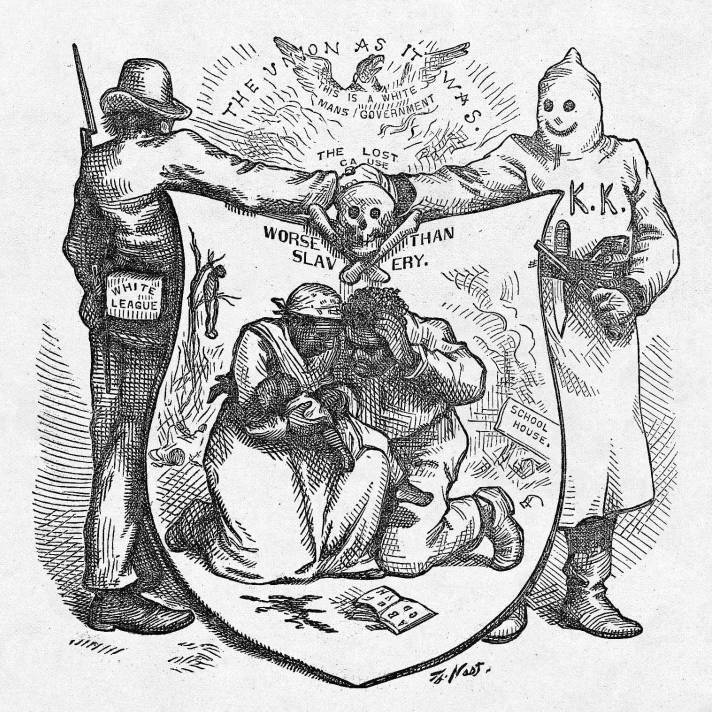

Resentful whites in Louisiana organized the White League to terrorize African Americans. Read one call for supporters:

Can you bear it longer, that negro [sic] ignorance, solidified in opposition to white intelligence, and led by carpet-bag and scalawag impudence and villainy, shall continue to hold the State, your fortunes and your honor by the throat, while they perpetuate upon you indignities and crimes unparalleled?

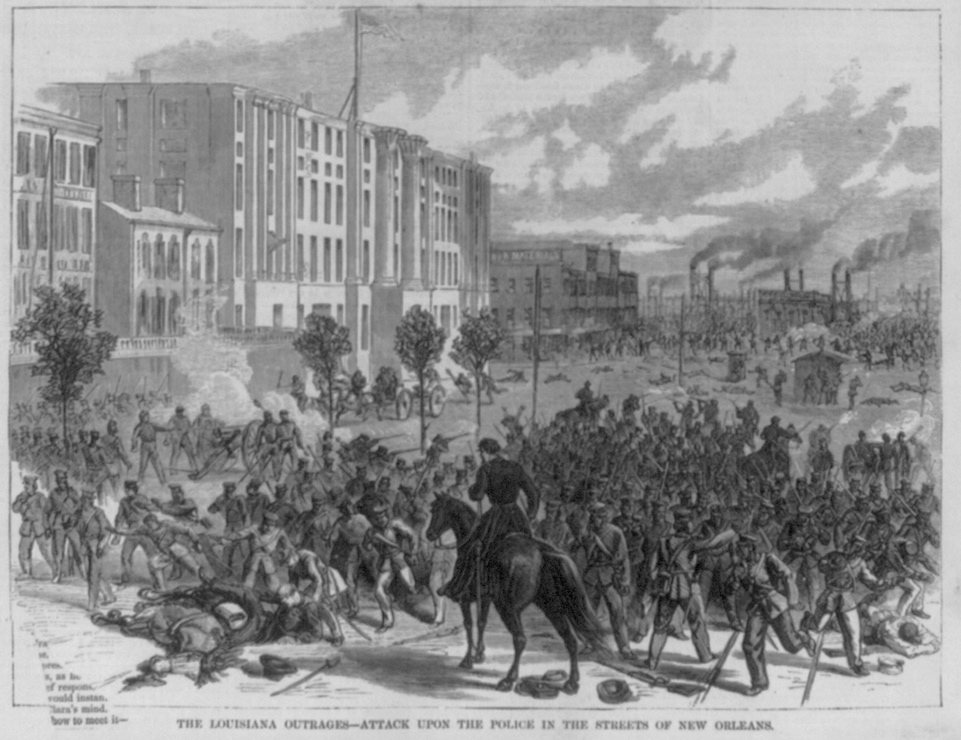

The White League, made up largely of former Confederate soldiers and the white business elite, was dedicated to the reestablishment of white supremacy. In September 1874, the League overwhelmed the state militia and seized control of state government offices. The attack left 27 Republican supporters of Reconstruction dead, including 24 African Americans and three whites. President Ulysses S. Grant had to order a squadron of six warships and federal troops to New Orleans in order to force the White League to surrender.

Reconstruction was overthrown by a political movement known as Redemption, which reestablished white supremacy in the South. Some upper-class white Southern conservatives, such as Wade Hampton, a wealthy South Carolinian, attempted to draw black voters away from the Republican Party. In 1876, when he ran for governor, he told African American voters:

We want your votes; we don’t want you to be deprived of them…. if we are elected…we will observe, protect, and defend the rights of the colored man as quickly as any man in South Carolina.

But the main strategy used to overthrow Reconstruction was economic intimidation and physical violence. Secret organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan, founded in Tennessee in 1866, and the Knights of the White Camellia were dedicated to ending Republican rule and preventing blacks from voting. Members of these organizations include judges, lawyers, and clergymen as well as yeomen farmers and poor whites.

The Redeemers had no scruples about fraud or terror. “Every Democrat,” said a South Carolina Redeemer, “must feel honor bound to control the vote of at least one negro by intimidation, purchase…or as each individual will determine.” Hundreds of blacks were beaten and murdered by the Ku Klux Klan and other white terrorist groups.

In 1870 and 1871, Congress passed the Force Act and the Ku Klux Klan Act which gave the president the power to use federal troops to prevent the denial of voting rights. Activities of groups like the Ku Klux Klan declined, but the campaign of intimidation was successful in keeping many African Americans from the polls. By 1876, Republican governments had been toppled in all but three states.

The End of Reconstruction

Among the factors that contributed to the end of Reconstruction were white terror, a split within the Republican party over corruption in the administration of President Ulysses S. Grant, and the North’s declining interest in protecting the rights of African Americans.

Retirement and death removed from Congress the more outspoken advocates of civil rights, such as Thaddeus Stevens, who died in 1868. Corruption in the Grant administration divided the Republican Party and helped the Democrats win control of the House of Representatives in 1874. Corruption in the South’s Republican government also undercut support for Reconstruction. Northern outrage over Southern intransigence gave way to helpless resignation or indifference.

As early as 1872, many former abolitionists believed that their aims had been achieved. Slavery had been abolished and citizenship and voting rights had been established by Constitutional Amendment. Democrats denounced “foreign” rule of the South by carpetbaggers and attacked corruption in President Grant’s administration. In 1872, “Liberal Republicans,” repelled by the supposed corruption of the radical regimes in the South, declared that the North had attained its goals and that Reconstruction should end. Many threw their support to the Democrats. The nationwide economic depression of 1873 further weakened the Republican Party, and Democrats regained the House of Representatives in 1874.

The financial panic of 1873 and the subsequent economic depression helped bring Reconstruction to a formal end. Across the country, but especially in the South business failures, unemployment, and tightening credit heightened class and racial tensions and generated demands for government retrenchment.

Property owners in the South demanded that state budgets be cut and tax rates lowered. Southern penitentiaries were dismantled and convicts were leased to private contractors. Spending on public schools and the care of orphans, the sick, and the mentally ill was sharply reduced. Budgets for schools for blacks were cut especially heavily.

It was, however, the disputed presidential election of 1876 that brought Reconstruction to a formal end.

Podcast

Why Was the Turn of the Century South the Poorest Part of the U.S.?

Listen to the following podcast.

Before the Civil War, the South was one of the wealthiest regions in the world. Afterwards, it was by far the nation’s poorest region. Only after World War II would the South begin to reach parity with the North and West.

The Disputed Presidential Election of 1876

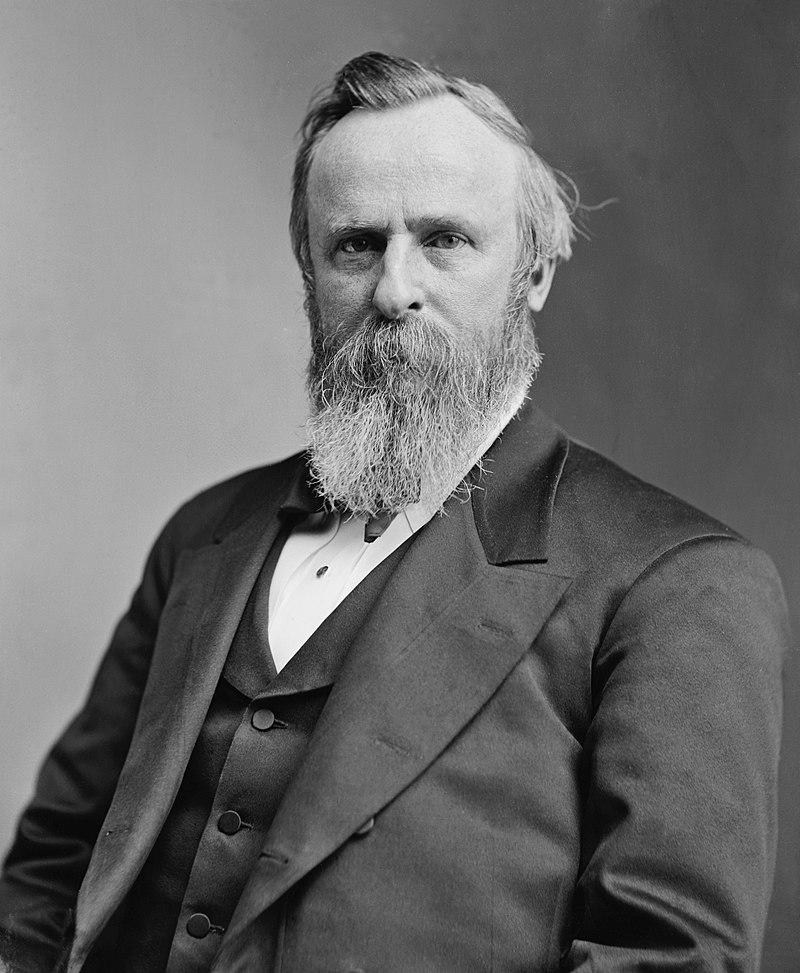

In the election of 1876, the Republicans nominated Rutherford B. Hayes, the governor of Ohio, while the Democrats, out of power since 1861, selected Samuel J. Tilden, the governor of New York. The initial returns pointed to a Tilden victory, as the Democrats captured the swing states of Connecticut, Indiana, New Jersey, and New York. By midnight on Election Day, Tilden had 184 of the 185 electoral votes needed to win. He led the popular vote by 250,000.

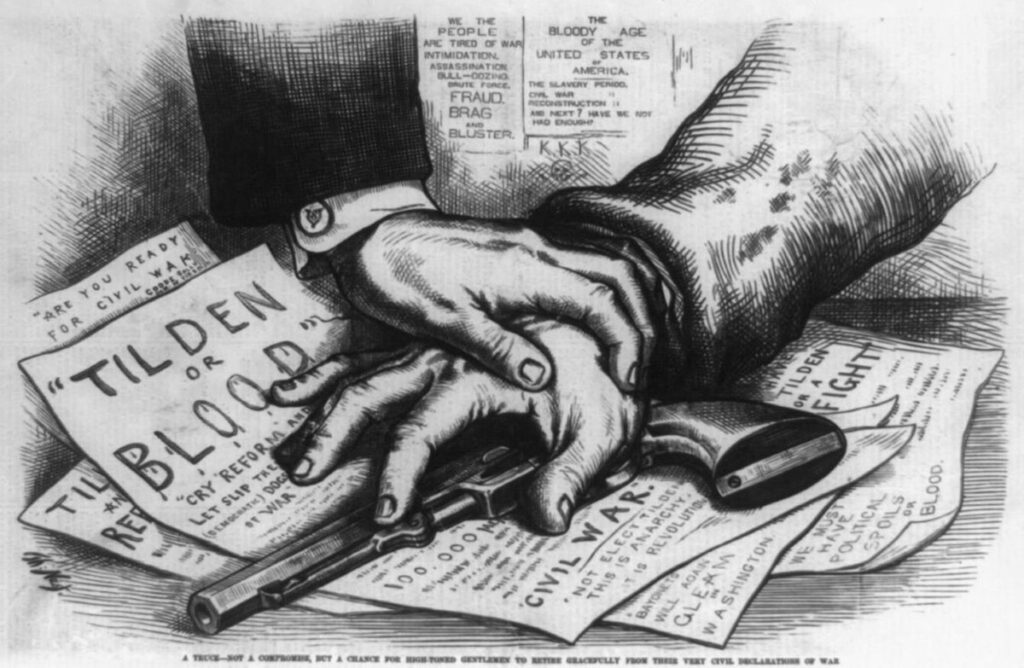

But Republicans refused to accept the result. They accused the Democrats of using physical intimidation and bribery to discourage African Americans from voting in the South.

The final outcome hinged on the disputed results in four states—Florida, Louisiana, Oregon, and South Carolina—which prevented either candidate from securing a majority of electoral votes.

Republicans accused Democrats in Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina of refusing to count African American and other Republican votes. Democrats, in turn, accused Republicans of ignoring many Tilden votes. In Florida, the Republicans claimed to have won by 922 votes out of about 47,000 cast. The Democrats claimed a 94 vote victory. Democrats charged that Republicans had ruined ballots in one pro-Tilden Florida precinct by smearing them with ink.

Both Democrats and Republicans in Oregon acknowledged that Hayes had carried the state. But when the Democratic governor learned that one of the Republican electors was a federal employee and ineligible to serve as an elector, he replaced him with a Democratic elector. The Republican elector, however, resigned his position as a postmaster and claimed the right to cast his ballot for Hayes.

Florida, Louisiana, Oregon, and South Carolina each submitted two sets of electoral returns to Congress with different results. To resolve the dispute, Congress, in January 1877, established an electoral commission made up of five U.S. representatives, five senators, and five Supreme Court justices. The justices included two Democrats, two Republicans, and Justice David Davis, who was considered to be independent. But before the commission could render a decision, Democrats in the Illinois legislature, under pressure from a nephew of Samuel Tilden, elected Davis to the U.S. Senate, in hopes that this would encourage Davis to support the Democrat. Instead, Davis recused himself and was replaced by Justice Joseph Bradley.

Bradley was a Republican, but he was considered one of the court’s least political members. In the end, however, he voted with the Republicans. A Democrat representative from New York, Abraham Hewitt, later claimed that Bradley was visited at home by a Republican Senator on the commission, who argued that “whatever the strict legal equities, it would be a national disaster if the government fell into Democratic hands.”

Bradley’s vote produced an eight-to-seven ruling, along straight party lines, to award all the disputed elector votes to Rutherford B. Hayes. This result produced such acrimony that many feared it would incite a second civil war.

Democrats threatened to filibuster the official counting of the electoral votes to prevent Hayes from assuming the presidency.

At a meeting in February 1877 at Washington, D.C.’s Wormley Hotel (which was operated by an African American), Democratic leaders accepted Hayes’s election in exchange for Republican promises to withdraw federal troops from the South, provide federal funding for internal improvements in the South, and name a prominent white Southerner to the president’s cabinet. When the federal troops were withdrawn, the Republican governments in Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina collapsed, bringing Reconstruction to a formal end.

Under the so-called Compromise of 1877, the national government would no longer intervene in Southern affairs. This would permit the imposition of racial segregation and the disfranchisement of black voters.

Why Did Reconstruction Fail?

In one section of Northern Carolina, a judge counted seven hundred beatings and twelve murders during Reconstruction.

Historians consider Reconstruction this country’s greatest failure. But why did it fail? Why did the sacrifice of hundreds of thousands of lives not result in greater economic and political equality for African Americans? Could it have succeedead?