A New History for a New Century

Why Study History?

Historical illiteracy is not a victimless crime. Those without a knowledge of history lack essential cultural literacy, and are unable to make sense of a host of cultural references. Those who know no history are also vulnerable to many fallacies, delusions, and mistaken beliefs.

History, it has been said, is “bunk” (Henry Ford), a “pack of lies the living play on the dead” (Voltaire), a register of humanity’s “crimes, follies, and misfortunes” (Edward Gibbon), or merely “one damned thing after another” (Arnold J. Toynbee).

But history is more than those things. It is the sum total of human experience in all its complexity. It is also the only guide we have to the decisions that will shape our future. The study of history allows us to see parallels, analogies, and recurrent patterns, detect long-term trends and forces, and understand what is really different about the present.

History shows us how past decisions shape and limit future options and how every facet of life is socially and culturally constructed. Equally important, history exposes us to the full richness of human experience and introduces us to fascinating individuals and events and to long-term processes that gradually transform our lives.

Lessons of History

Historical Lessons

History truly does offer lessons that we repeatedly fail to learn. Too often, the supposed lessons of history are too simplistic.

- That power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely.

- That those who forget the past are doomed to repeat it.

- That appeasing dictators leads to larger conflicts in the future.

But there are more meaningful lessons that history offers:

- That each time experts tell you that “this time is different”—that old rules no longer apply, and that circumstances today bear no similarity to the past—they are almost always wrong.

- That it is a mistake to believe that today’s problems are worse than those in the past or that one aspect of life or another is getting worse and worse.

- That few historical events are inevitable, but are, rather, the product of human choice, action, and inaction.

- That war has uncontrollable consequences and every policy intervention has unintended results.

Knowledge about the past is more important than ever in the twenty-first century. Our society’s most pressing problems are rooted in history. Those without an understanding of history lack an essential resource for navigating our ever-changing world.

Varieties of History

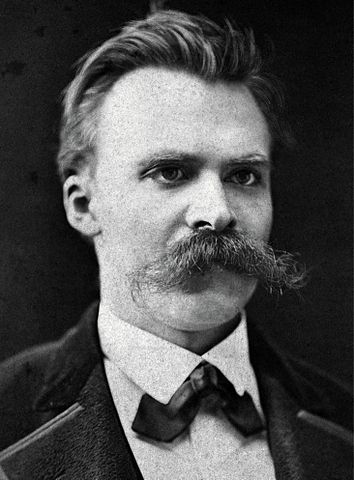

The great German philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche, identified three kinds of history. First, there is popular history, which consists of tales of “Great Men” and great events that offer simplistic lessons to the present. This approach to history, in his mind, was engaging but inconsequential.

Then there is antiquarian history, the effort to recount the past “as it really was.” This kind of history makes no effort to understand why history might be significant, relevant, or meaningful.

The kind of history that Nietzsche praised was “critical history” in which the past is interrogated, interpreted, and judged. The purpose of this form of history is to free us from myths, misconceptions, delusions, and false assumptions and to lay bare the historical processes that are reshaping our lives. This is the form of history that we will study.

Historical Thinking

Like psychology and sociology, history is a distinctive way of thinking. It teaches us that everything—every institution, custom, and social role—has evolved over time, and will continue to evolve in the future. Even seemingly “bedrock” biological processes have a history. The age at which a young woman first menstruates or that young people achieve their adult height and even how long people live have shifted profoundly over time.

History reminds us that few things in life are unambiguously evil or good, that even the worst perpetrators of evil had reasons that they regarded positively for what they did. In addition, history demonstrates that events rarely progress in a linear or straightforward fashion and that every event is contingent and could have turned out otherwise, producing a very different world today.

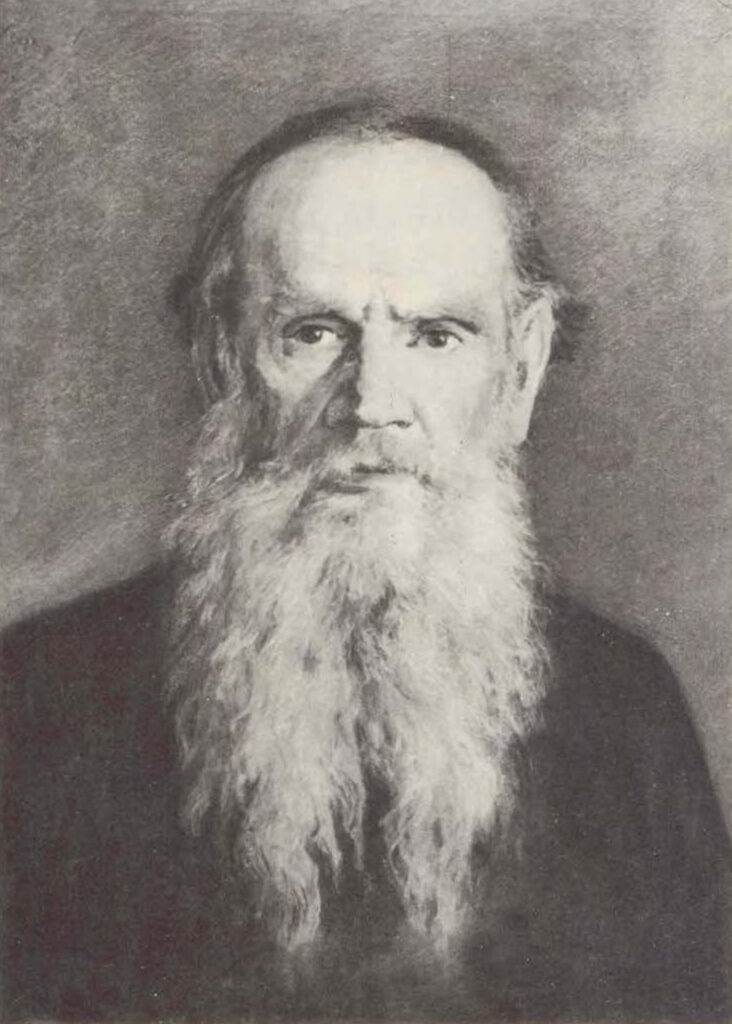

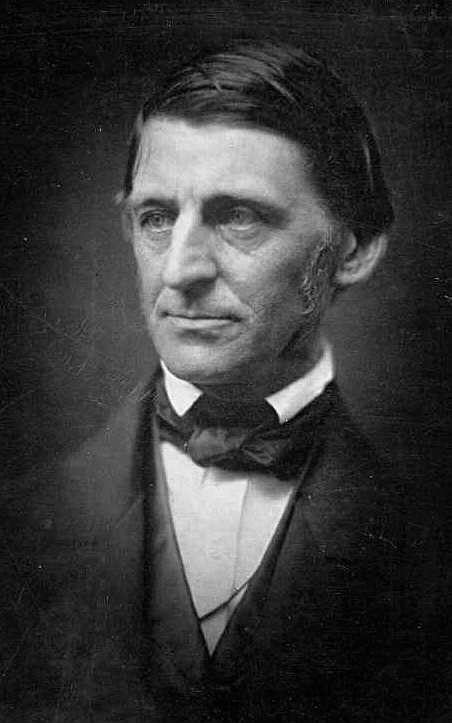

In his epic novel, War and Peace, Leo Tolstoy lays out two opposing conceptions of history. On the one hand, there are those who regard history as Ralph Waldo Emerson did: As the lengthened shadow of influential individuals, whose choices, actions, and ambitions and even their eccentricities and irrationalities prove decisive in shaping the course of events. This view emphasizes the importance of human agency and the ability of mighty individuals to shape the future.

On the other hand, there is the contrasting view that no individual, no matter how powerful, is truly free, since even the most powerful individual is in the grip of circumstances, ideologies, and long-term forces that ultimately drive the course of history. In this view, history is not made by “Great Men”, but by the unfolding of innumerable interconnected processes and events.

Both views, of course, contain elements of truth, and in this class we will examine the complexities of human nature, the causes, course, and consequences of decisive events, and the gains and losses that accompany social and political change.

We will study history not because it offers a storehouse of simple lessons that can be applied to the present, but because it is a way of thinking, one that emphasizes change over time, the shaping power of context, and the importance of contingency—the reality that the future is utterly unpredictable.

In studying history, certain themes stand out:

- “All is flux”

2,500 years ago, a Greek philosopher, Heraclitus, declared that change is a constant and that nothing stays stable. Across history, nothing is static. Great powers rise and fall. Migrations alter populations. Even the most mundane aspects of life—our holidays, sports, naming patterns—have a history. - “We cannot escape history”

When Abraham Lincoln used that phrase in his 1862 annual address to Congress, he meant that our decisions and actions carry lasting consequences. But we cannot escape history in other senses as well. Our lives are caught up in long-term historical processes and many of society’s most pressing problems are rooted in the past. - “Judging the past”

To understand history fully, we need to recognize that the past is another country, with its own culture, circumstances, and moral frameworks. Only by placing past decisions or attitudes in their proper historical context, only by understanding, and to a certain extent empathizing with, a particular individual’s perspective, can we truly understand why people acted as they did.

This is not to say that we cannot cast judgment through the lens of contemporary moral standards, but our conclusions need to be tempered by an understanding of the circumstances and climate of the time. - “Nothing is inevitable until it happens.”

So said the great British historian A. J. P. Taylor. Few things in history are predictable or unavoidable. Rather, they are contingent. They are dependent on a host of variables: chance, personality, mindsets, individual and collective choices, and circumstances that cannot be fully foreseen. Events only seem inevitable after the fact. - “The study of history is a study of causes.”

With those words, the English historian E.H. Carr insisted that history’s primary task is to understand the confluence of factors and conjuncture of forces that contribute to historical change. There is a role for the individual in driving change, he argued, but also for ideologies or systems of belief, social forces, institutional imperatives, and long-term historical processes over which individuals have limited control. - “History is problem solving”

Doing history is not simply a matter of collecting facts in order to produce an objective portrait of the past. Rather, it involves answering questions. Some questions are narrow; these include “What happened?”, “Why did it happen?”, and “What effect did it have?” Other questions are more analytic: “What role did racism or fear of the Soviet Union play in the decision to use nuclear weapons against Japan?” Some are broad, and, at times, overly broad: “How did geography influence the development of colonial America?” or “Was the Civil War inevitable?” In general, the best historical questions do not have simple “yes” or “no” answers but require a nuanced response.

History offers few clear-cut lessons. But it can be a source of wisdom. It reminds us that political decisions and policies tend to have unexpected, unintended, and, sometimes, uncontrollable consequences. That human beings tend to exaggerate present-day problems out of proportion. That people make history, but, as Karl Marx put it in 1852, “they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.”

How, then, might history help us think differently about the present-day United States?

First, it reminds us that contemporary battles over politics, policy, and values are only the most recent iteration of an ongoing moral civil war: About the role of government, equality and inequality, and the rights of the individual. Contestation over basic values has marked our past and continues to define the present.

Secondly, it prompts us to remember that just as we are the heirs of this country’s past achievements, we bear responsibility for this country’s past errors and immoral acts. All of us benefit from this country’s enormous wealth and power. But past inequities, especially in terms of race and gender, and wrong-headed choices, especially in foreign affairs, carry lasting consequences.

Thirdly, historical perspective encourages us to think in a more nuanced way about whether various aspects of our society are getting better or going to the dogs. Genuine progress has been achieved in many areas – people’s income, health, and well-being have increased and many barriers to equality have been removed. Our moral consciousness, too, has expanded. But history suggests that progress inevitably produces new problems and leaves many earlier problems unresolved. We should not minimize the accomplishments of earlier generations. But we must also recognize that there is no end to history—that contests and conflicts over values and power will go on and on.

This Class’s Approach

The history that you will learn in this class will not be like the history you learned in high school.

It will be:

- Comparative

- The United States was not unique in beginning as a European colony, experiencing conflict between settlers and indigenous peoples, importing African slaves, waging a revolution against colonial rule, expand toward a frontier, admitting large numbers of immigrants, or undergoing an industrial revolution. It is only by placing the United States in comparative perspective that we can understand what is truly distinctive about this country.

- Multicultural

- The United States is the most diverse country in the world, and the history we will explore will reflect that fact. Cultural diversity is not a new development. This country was even more diverse linguistically, racially, and culturally in the colonial era and again at the turn of the twentieth century.

- Multi-dimensional

- Political history, military history, and diplomatic history have a place in this course. But so does the history of everyday life, business, technology and invention, and popular culture.

But the most important difference between this class and those you took earlier is that you will actually do history.

So let’s jump in and tackle our first challenges.