The Battle of Little Big Horn

Hollywood Versus History

Custer’s “Last Stand”

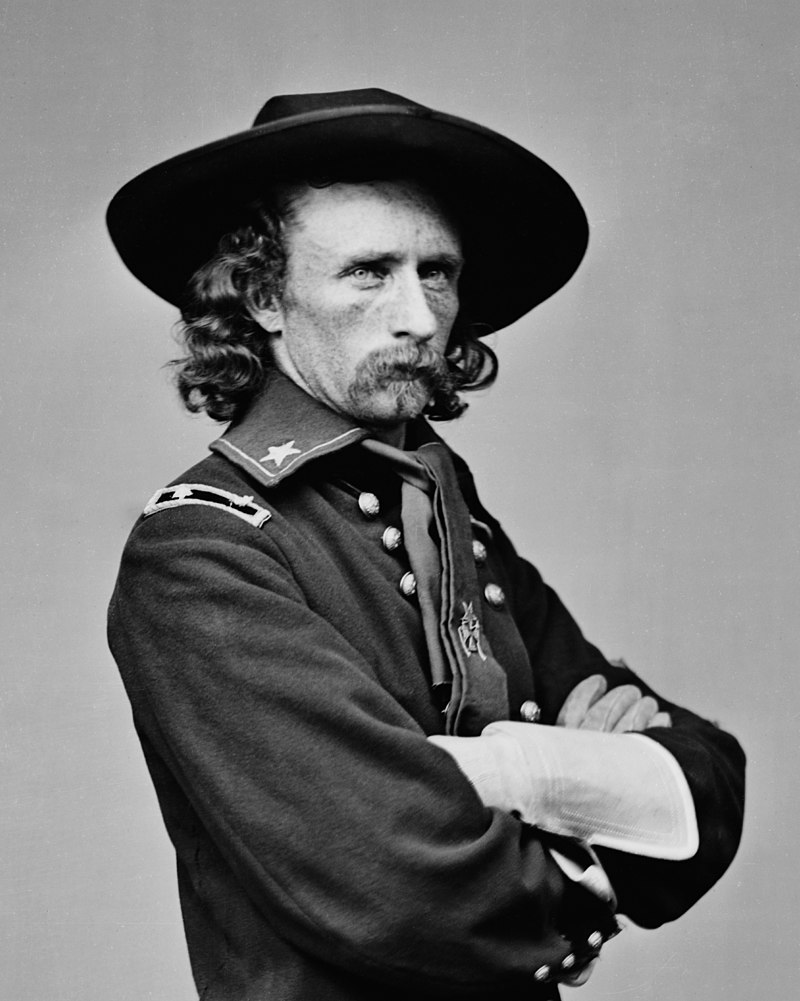

Hollywood film star Errol Flynn portrayed him as the personification of American heroism, as an officer who died with his boots on. Decades later, the film Little Big Man depicted him as a narcissistic goldilocks and a psychopathic killer. Today, Custer’s defeat at the battle of the Little Big Horn remains the single most studied military engagement in American history, and writers still debate whether Custer was a racist murderer; a swaggering, egotistical self-promoter; or a martyred hero betrayed by his subordinates. Historians tend to view him as an officer whose vanity, youth, and desire for victory clouded his tactical judgment.

The Ohio-born Custer graduated last in his class at West Point in 1861, but by the age of twenty-five he had risen to the rank of brevet major general, the Army’s youngest. He fought in many Civil War battles including Gettysburg, and became one of the heroes of the Union army. At the end of the Civil War, he reverted to his Army rank of captain and served stints in Louisiana and Texas before being placed in command of the Seventh Cavalry on the Great Plains.

In 1874, he led an expedition into the Black Hills of what is now South Dakota, which was then reserved for the Sioux. He brought along reporters and geologists, who informed the public that there was “gold in the grass roots.” This led to a stampede of prospectors and miners into the Black Hills. President Ulysses Grant ordered all Indians to register at reservations. Many Sioux and Cheyenne gathered in southeastern Montana and decided to resist.

On June 25, 1876, Custer’s scouts had observed what they thought was a retreating Indian village along the Little Big Horn River in what is now Montana. Custer knew that the Plains Indians usually scattered when attacked in order to protect non-combatants. He expected them to disperse when his men struck. Only two years earlier, Custer had staged a surprise, early morning attack on the camp of a southern Cheyenne Chief, Black Kettle, along the banks of Oklahoma’s Washita River, in which 103 Indians, mostly women, children, and the elderly, had been killed.

But this Indian village was far larger than Custer imagined. It contained an estimated 8,000 Indians and more than 3,000 warriors and was led by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. The village was three miles long and a half mile wide. Custer had initially estimated the village’s population did not exceed 1,500. Custer divided his command of 645 soldiers into three columns. Major Marcus Reno’s detachment approached the Indian camp from the southeast and lost a third of its men. Reno’s men retreated to a nearby ridge, where they were under siege for nearly two days.

Meanwhile, the buckskin-clad Custer and his men tried to open an attack on the Indians’ flank. But the Indians had watched Custer lead his men along the bluffs overlooking the Little Big Horn, and 1,500-2,500 warriors attacked Custer’s forces. His men, many of whom were raw recruits, were ill-prepared for combat. Lacking cover and relying on single-shot rifles, Custer’s troops fired few bullets. In contrast, many of the Indians were carrying repeating rifles and carbines. Within an hour, every soldier in Custer’s command had died. Indian losses in the battles totaled less than a hundred.

Surviving letters and other documents give a human dimension to the battle. Many of Custer’s troops were young immigrants and farm boys who lived a miserable existence on the Plains. They were forced to wear wool uniforms year-round and ate salt pork and hardtack, a cracker-like food that had to be soaked in water or coffee to be edible. The men drank heavily in order to pass the time.

One of Custer’s men, Isaiah Dorman, was a former slave who had lived among the Sioux for several years before serving as a translator for Custer during the Little Big Horn campaign. His corpse was particularly mutilated because he was regarded as a traitor for leading the Americans to the Sioux. A 25-year-old second lieutenant, George D. Wallace, described Custer’s camp at the mouth of the Big Horn River. “The Indians surrounded us & poured in a deadly fire, but we had to lie still and take it…,” he wrote. “The next morning we moved to the scene of Gen’l Custer’s fight, but the sight was too horrible to describe. We buried 204 bodies and encamped near Gen’l [Alfred H.] Terry. But the smell of dead horses forced him to move camp several miles.” Wallace died in 1890, one of 31 soldiers killed during the assault on a group of 350 Sioux men, women, and children at Wounded Knee in South Dakota.

Custer’s “Last Stand” also marked the Plains Indians’ last stand. The shocking news of Custer’s defeat arrived in the east two days after the nation’s centennial, and encouraged a thirst for revenge. The Plains Indians suffered a series of defeats following the battle. The Indian alliance was shattered and Sitting Bull and some of his people fled to Canada. Buffalo Bill Cody would advertise himself as the first soldier to scalp an Indian in retaliation for Custer’s defeat. Within a year, nearly all the Plains Indians had been confined on reservations.

In 1877, during a meeting under a flag of truce in Fort Robinson, Nebraska, an American soldier killed Crazy Horse by stabbing him with a bayonet.

Black Elk, an Indian medicine man, said that before his murder Crazy Horse had told him: “I will return to you in stone.” In 1998, a Connecticut sculptor, Korczak Ziolkowski, completed an 87-foot-tall bust of Crazy Horse in South Dakota’s Black Hills. Located 17 miles from Mount Rushmore, where the heads of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt were carved in a mountainside in the Sioux homeland during the 1930s, Crazy Horse’s face rises higher than the Washington Monument and is more than twice the height of the Statue of Liberty.

The Battle of the Little Big Horn is still regarded as one of the defining events in American history. More than a century after the battle, books continue to be published and Custer’s character and decisions continue to be debated.

Nez Perce

The last great war between the U.S. government and an Indian nation ended at 4 p.m., October 5, 1877, in the Bear Paw Mountains of northern Montana. Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce nation surrendered 87 men, 184 women, and 147 children to units of the U.S. cavalry. For eleven weeks, he led his people on a 1,600-mile retreat toward Canada. He engaged ten separate U.S. commands in thirteen battles and skirmishes, and in nearly every instance he either defeated the American forces or fought them to a standstill. But in the end, the Nez Perce proved no match for Gatling guns, howitzers, and cannons.

At that moment, Joseph delivered one of the most eloquent speeches in American history. He spoke no English, but his translated remarks having handed his rifle to Colonel Nelson Miles, Joseph concluded:

The little children are freezing to death…. I want to have time to look for my children and see how many I can find…. Hear me, my chiefs. I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.

One of his terms of surrender was that his people be returned to their homeland.

For thirty-one years, Joseph fought for his peoples’ return to eastern Oregon’s Wallowa Valley, where his people had produced the famous Appaloosa horse, bred for speed and endurance. He met with three American presidents to argue his case: Rutherford Hayes, William McKinley, and Theodore Roosevelt. He died at the age of 64 in 1904.

In 1877, the U.S. government sent General Oliver Howard to force the Nez Perce to move to an Idaho reservation. Chief Joseph and his band left for the reservation, but before they could reach it, several Nez Perce youths, disillusioned by broken treaty promises and white encroachment on their land, attacked and killed eighteen white settlers.

Chief Joseph then began a three month, 1,600-mile flight to Canada with four separate U.S. military units in pursuit. The Nez Perce repeatedly turned the tables on numerically superior forces. They eluded and out-fought 2,000 army soldiers in thirteen battles before finally surrendering in a Montana snowstorm, just forty miles from the Canadian border. Only 418 men, women, and children out of 800 who had set out were left. During the final battle, General Miles attempted to seize Chief Joseph under a flag of truce, but the chief had to be exchanged when the Nez took a white lieutenant prisoner.

Under the terms of the surrender, the Nez Perce were promised that they could live on a reservation in Lapwai, Idaho. But instead the Nez Perce were sent to Oklahoma. Half the tribe died from disease on the trip. A decade later the Nez Perce were relocated on a reservation in eastern Washington.

The surrender of Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce ended a decade of warfare between Indians and the U.S. government in the Far West. It meant that virtually all western Indians had been forced to live on government reservations.