Tragedy of the Plains Indians

A Thirty Years War

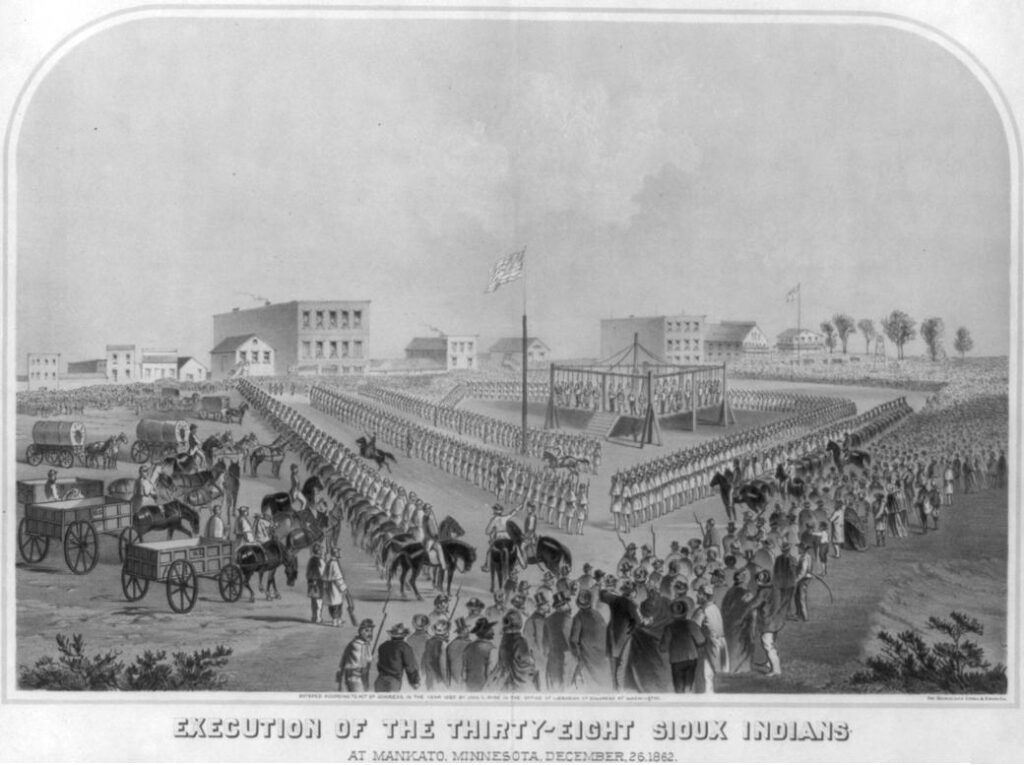

Beginning in the 1860s, a 30-year conflict arose as the government sought to concentrate the Plains tribes on reservations. Philip Sheridan, a Civil War general who led many campaigns against the Plains Indians, is famous for saying “the only good Indian is a dead Indian.” But even he recognized the injustice that lay behind the late nineteenth century warfare:

We took away their country and their means of support, broke up their mode of living, their habits of life, introduced disease and decay among them, and it was for this and against this that they made war. Could anyone expect less?

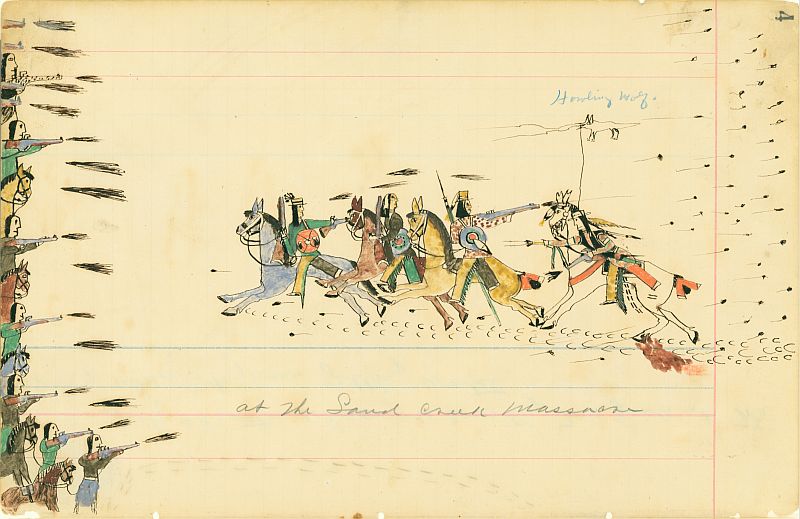

In 1864, warfare spread to Colorado, after the discovery of gold led to an influx of whites. Because the regular army was fighting the Confederacy, the Colorado territorial militia was responsible for maintaining order. On November 29, 1864, a group of Colorado volunteers, under the command of Colonel John M. Chivington, fell on Chief Black Kettle’s unsuspecting band of Cheyennes at Sand Creek in eastern Colorado, where they had gathered under the protection of the governor. “We must kill them big and little,” he told his men. “Nits make lice” (nits are the eggs of lice). The militia slaughtered about 150 Cheyenne, mostly women and children.

Violence broke out on other parts of the Plains. Between 1865 and 1868, conflict raged in Utah. In 1866, the Teton Sioux, tried to stop construction of the Bozeman Trail, leading from Fort Laramie, Wyoming to the Virginia City, Wyoming, gold fields, by attacking and killing Captain William J. Fetterman and 79 soldiers.

The Sand Creek and Fetterman massacres produced a national debate over Indian policy. In 1867, Congress created a Peace Commission to recommend ways to reduce conflict on the Plains. The commission recommended that Indians be moved to small reservations, where they would be Christianized, educated, and taught to farm.

At two conferences in 1867 and 1868, the federal government demanded that the Plains Indians give up their lands and move to reservations. In return for supplies and annuities, the southern Plains Indians were told to move to poor, unproductive lands in Oklahoma and the northern tribes to the Black Hills of the Dakotas. The alternative to acceptance was warfare. The commissioner of Indian Affairs, Ely S. Parker, himself a Seneca Indian, declared that any Indian who refused to “locate in permanent abodes provided for them, would be subject wholly to the control and supervision of military authorities.” Many whites regarded the Plains Indians as an intolerable obstacle to westward expansion. They agreed with Theodore Roosevelt that the West was not meant to be “kept as nothing but a game reserve for squalid savages.”

Leaders of several tribes—including the Apaches, Arapahos, Cheyennes, Kiowas, Navajos, Shoshones, and Sioux—agreed to move onto reservations. But many Indians rejected the land cessions made by their chiefs.

In the Southwest, war broke out in 1871 in New Mexico and Arizona with the massacre of more than 100 Indians at Camp Grant. The Apache War did not end until 1886, when their leader, Geronimo was captured. On the southern Plains, war erupted when the Cheyennes, Comanches, and Kiowas staged raids into the Texas panhandle. The Red River War ended only after federal troops destroyed Indian food supplies and killed a hundred Cheyenne warriors near the Sappa River in Kansas. This brought resistance on the southern Plains to a close. In the Pacific Northwest, the Nez Perce of Oregon and Idaho rebelled against the federal reservation policy and then attempted to escape to Canada, covering 1,300 miles in just seventy-five days. They were forced to surrender in Montana, just forty miles short of the Canadian border. Chief Joseph, the Nez Perce leader, offered a poignant explanation for why he had surrendered:

I am tired of fighting…The old men are all killed…The little children are freezing to death…From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.

After their surrender, the Nez Perce were taken to Oklahoma, where most died of disease.

The best-known episode of Indian resistance took place after miners discovered gold in the Black Hills—land that had been set aside as a reservation “in perpetuity.” When thousands of miners staked claims on Sioux lands, war erupted, in which an Indian force led by Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull killed General George Custer and his 264 men at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. “Custer’s Last Stand” was followed by five years of warfare in Montana that confined the Sioux to their reservations.

Several factors contributed to the defeat of the Plains Indians. One was a shift in the military balance of power. Before the Civil War, an Indian could shoot thirty arrows in the time it took a soldier to load and shoot his rifle once. The introduction of the Colt six-shooter and the repeating rifle after the Civil War, undercut this Indian advantage. During the 1870s, the army also introduced a new military tactic—winter campaigning. The army attacked Plains Indians during the winter when they divided into small bands, making it difficult for Indians effectively to resist.

Another key factor was the destruction of the Indian food supply, especially the buffalo. In 1860, about thirteen million roamed the Plains. These animals provided Plains Indians with many basic necessities. They ate buffalo meat, made clothing and tipi coverings out of hides, used fats for grease, fashioned the bones into tools and fishhooks, made thread and bowstrings from the sinews, and even burned dried buffalo droppings (“chips”) as fuel. Buffalo also figured prominently in Plains Indians’ religious life. After the Civil War, the herds were cut down by professional hunters, who shot 100 an hour to feed railroad workers, and by wealthy easterners who killed them for sport. By 1890, only about 1,000 bison remained alive. Government officials quite openly viewed the destruction of the buffalo as a tool for controlling the Plains Indians. Secretary of the Interior Columbus Delano explained in 1872, “as they become convinced that they can no longer rely upon the supply of game for their support, they will return to the more reliable source of subsistence….”

The Sand Creek Massacre

Senator Ben Nighthorse Campbell of Colorado, the lone American Indian in Congress, called it “one of the most disgraceful moments in American history.” About 700 U.S. army volunteers stormed through an Indian encampment near Big Sandy Creek in Colorado, slaughtering scores of women and children. This episode became known as the Sand Creek Massacre.

n the Spring of 1864, a wing of the Cheyenne tribe unleashed attacks on white settlers, which prompted John M. Chivington, a Methodist minister who had become Colorado’s military commander and was eager to become a member of Congress, to call for volunteer Indian fighters for 100-day enlistments. On November 29, 1864, the colonel and his volunteers rode into the Arapaho-Cheyenne reservation, where Indians led by the Cheyenne chief Black Kettle had set up a camp weeks earlier. A white flag and an American flag flew above Black Kettle’s tepee.

After unleashing cannon fire into the village, the volunteers swept the Creek bed, killing every Indian they could find, often hunting down fleeing children. “Kill them big and small,” Chivington reportedly said, “nits become lice” (nits are the eggs of lice). After six hours, about 150 Indians, a quarter of the camp’s population, lay dead. The soldiers took three prisoners, all children. A dozen soldiers were killed, some apparently by friendly fire in the frenzy.

Eyewitness accounts are chilling. Lieutenant Joseph Cranmer described “a squaw ripped open and a child taken from her. Little children shot while begging for their lives.” Captain Silas Soule, who was assassinated after testifying at a congressional inquiry, said, “it was hard to see little children on their knees have their brains beat out by men professing to be civilized.” A joint congressional committee concluded that Chivington “deliberately planned and executed a foul and dastardly massacre, which would have disgraced the veriest savage among those who were victims of his cruelty.”

In response to the massacre, President Lincoln replaced Colorado’s territorial governor. A Congressional inquiry condemned the battle as a massacre. The Cheyenne and Arapaho were promised reparations in an 1865 treaty, but none were paid.

Injustice toward Native Americans is a longstanding theme in American history, from warfare, broken treaties, massacres, and the ruthless seizure of land to less obvious forms of violence, including discrimination, cultural stereotyping, and economic exploitation.