The Ranching and Farming Frontier

The Cattle Frontier

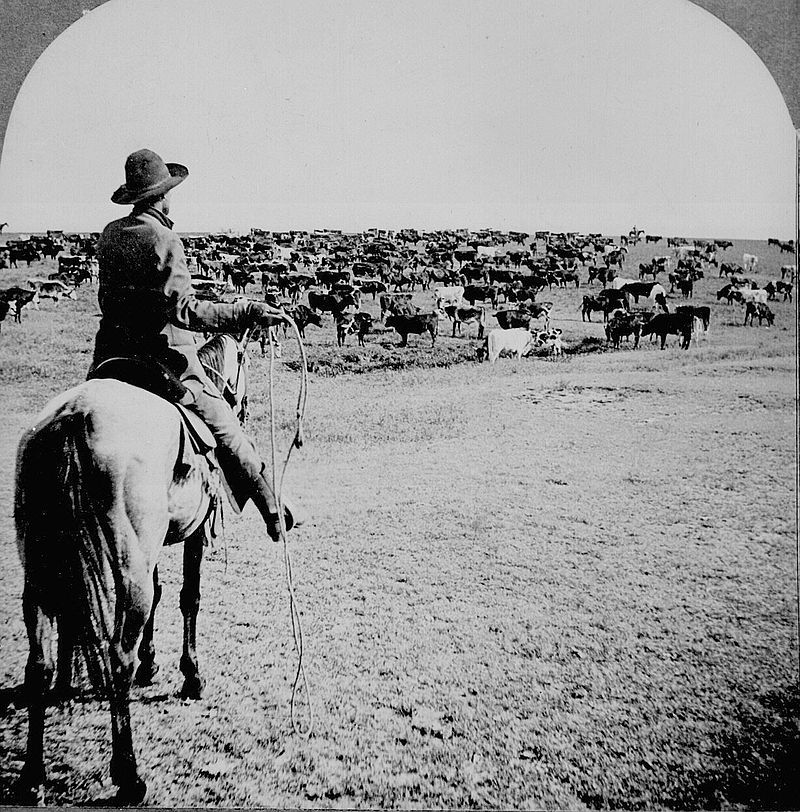

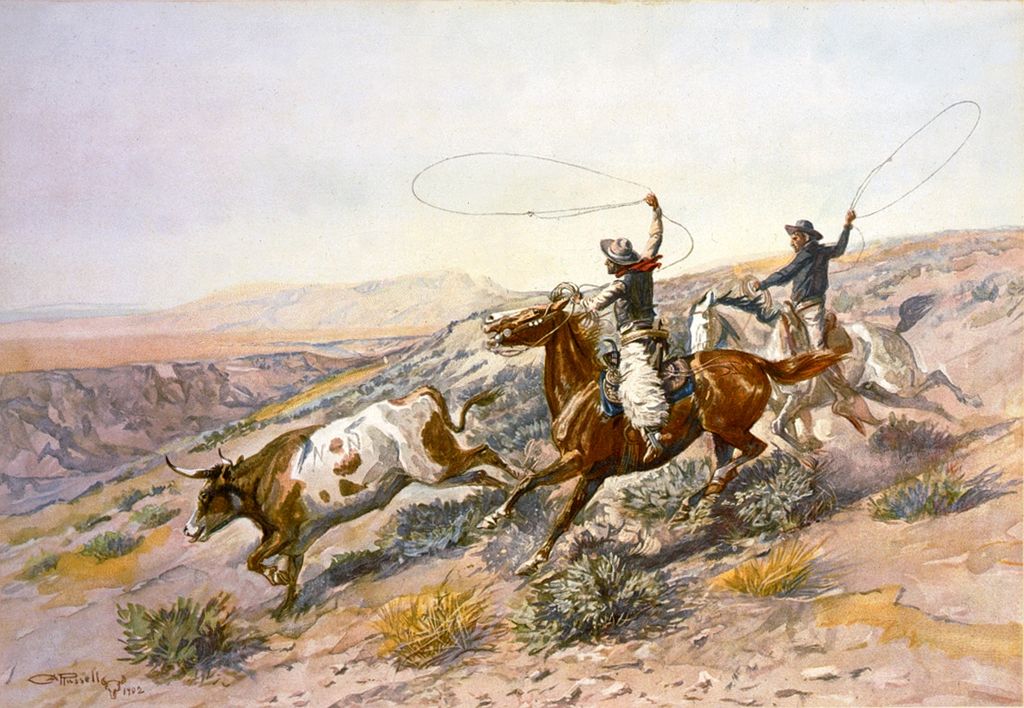

The development of the railroad made it profitable to raise cattle on the Great Plains. In 1860, some five million longhorn cattle grazed in the Lone Star state. Cattle that could be bought for $3 to $5 a head in Texas could be sold for $30 to $50 at railroad shipping points in Abilene or Dodge City in Kansas. Cowboys had to drive their cattle a thousand miles northward to reach the Kansas railheads.

Although the popular image of the cowboy is of John Wayne or Roy Rogers, many of the cowboys were African Americans or Mexican Americans. About one in five cowboys was a Mexican American and one in seven was black.

By the 1880s, the cattle boom was over. An increase in the number of cattle led to overgrazing and destruction of the fragile Plains grasses. Sheep ranchers competed for scarce water, and the sheep ate the grass so close to the ground that cattle could no longer feed on it. Bitter range wars erupted when cattle ranchers, sheep ranchers, and farmers fenced in their land using barbed wire. The romantic era of the long drive and the cowboy came to an end when two harsh winters in 1885-1886 and 1886-1887, followed by two dry summers, killed 80 to 90 percent of the cattle on the Plains. As a result, corporate-owned ranches replaced individually-owned ranches.

After the terrible winters, many ranchers decided to fence in their cattle rather than letting them roam freely. The invention of barbed wire made it possible to build fences without lumber and protect railroad tracks from stampeding animals. The first barbed wire was produced in 1868 and early barbed wire had to be manufactured by hand. Two strands of wire were wound together and barbs were then threaded through the wires.

A salesman, John “Bet a Million” Gates, helped convince ranchers to adopt barbed wire. (He received his nickname because he reportedly lost $1 million when he bet about which raindrop would slide down a train window the fastest). In San Antonio, Texas, Gates bet local ranchers that they could not drive steers out of a corral made up of eight strands of barbed wire.

The Farming Frontier

Farming on the Great Plains depended on a series of technological innovations. Lacking much rainfall, farmers had to drill wells several hundred feet into the ground to tap into underground aquifers. Windmill-powered pumps were necessary to bring the water to the surface and irrigate fields. Steel tipped plows were necessary to cut through the plains’ grasses dense roots. To make up for a scarcity of farm labor, farmers relied heavily on mechanical threshing machinery.

The Homestead Act

To encourage farmers to settle on the Great Plains, Congress passed the Homestead Act in 1862. This act allowed any citizen or any immigrant intending to become a citizen to get title to 160 acres of land by paying a small fee, living on the tract for five years, and making a few improvements. It also allowed settlers to pay $1.25 an acre and own the land immediately.

Homestead Patent No. 1 was granted to a Daniel Freeman in 1862 for a tract in Nebraska. Between 1862 and 1900, the Homestead Act provided farms to more than 400,000 families.

Homesteading proved to be very difficult. About a third of those who tried to develop homesteads eventually failed. On the Great Plains, rain was scarce and a farm or ranch of 160 acres was too small to be economical.

Water and the West

Water was more important than gold or silver or copper in the development of the American West. West of the 100th meridian, a year usually produces less than twenty inches of rainfall. Water was the lifeblood of the arid Plains. The availability of cheap water is an environmental factor that has made possible for such western cities as Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Salt Lake City to thrive.

At first, many farmers believed that “water follows the plow.” They deluded themselves that if they planted trees and built farms, rainfall would surely follow. It did not.

Windmills allowed late nineteenth century farmers to tap into underground aquifers. In the twentieth century, canals, aqueducts, and the damming of rivers transformed a vast, arid region into a region of sprawling cities and the nation’s richest farmland. Today, there are 1,200 major dams in California alone.

During the Great Depression, the construction of dams provided employment to the jobless and a cheap source of electric power. In the 1930s, five major water projects were constructed simultaneously, including the California Central Valley project that drained Tulare Lake, the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi. When the Hoover Dam was built during the Depression on the Colorado River, it was the largest dam on earth, standing 726 feet high. It was surpassed by the Grand Coulee Dam, which stretched 4,290 feet across the Columbia River and created a 150-mile-long lake as its reservoir. It opened in 1942 and for some time was the world’s single most powerful source of electricity. It was not until the 1970s, that environmentalists began to convince policy makers of the negative ecological consequences of extensive dam building.

Historical Facts & Fiction

Passenger Pigeons

The last dodo bird was seen in 1642. It was followed into extinction by a Great Auk in 1842. The last passenger pigeon died in 1914. Its remains one of the most eerie examples of extinction in history.

The passenger pigeon was once the most common bird in North America, making up about two-fifths of all birds on the continent. Flocks of passenger pigeons flew by the hundreds of millions, blotting out the sky for hours.

One flight over Columbus, Ohio, in 1855 was described with these vivid words:

As the watchers stared, the hum increased to a mighty throbbing. Now everyone was out of the houses and stores, looking apprehensively at the growing cloud, which was blotting out the rays of the sun. Children screamed and ran for home. Women gathered their long skirts and hurried for the shelter of stores. Horses bolted. A few people mumbled frightened words about the approach of the millennium, and several dropped on their knees and prayed.

But by the early twentieth century, the species had disappeared from the wild, with the last confirmed sighting in 1902. In 1912, the last passenger pigeon in captivity died in the Cincinnati zoo.

Passenger pigeons remain a part of our language, apparent in such phrases as stool pigeon, clay pigeon, and trap shooting.

How did the passenger pigeon go from a population of billions to zero in less than fifty years? Hunters killed the birds by the millions, sometimes using clubs or nets. The word stool pigeon originated in using a live bird to attract other birds into a net. Logging resulted in deforestation, destroying the birds’ natural habitat.

Indeed, it was the disappearance of the passenger pigeon and of bison that contributed to the growth of the environmental movement. Ironically, rich hunters helped lead this movement. The Boone and Crockett Club, founded for rich sportsmen in 1887, including Theodore Roosevelt, supported the first bird protection law, the Lacey Act of 1900.

The Western frontier occupies a particular important place in the American imagination. We sing of “purple mountains majesty” and the “fruited plain.” Western geysers, forests, gorges, vistas, and prairies help Americans think of their country as “Nature’s Nation,” a land of unparalleled natural beauty.

Yet many parts of the Transmississippi West are anything but pristine. Rather, one sometimes encounters abandoned mines and quarries, polluted streams, and strip mined hilltops.