Conclusion

Kill the Indian and Save the Man

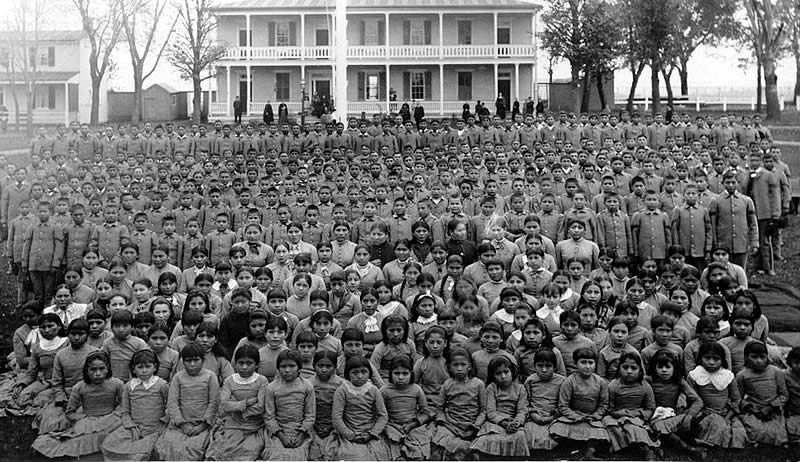

In 1879, an army officer named Richard H. Pratt opened a boarding school for Indian youth in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. His goal: to use education to uplift and assimilate into the mainstream of American culture. That year, fifty Cheyenne, Kiowa, and Pawnee arrived at his school. Pratt trimmed their hair, required them to speak English, and prohibited any displays of tribal traditions, such as Indian clothing, dancing, or religious ceremonies. Pratt’s motto was “kill the Indian and save the man.”

The Carlisle Indian School became a model for Indian education. Not only were private boarding schools established, so too were reservation boarding schools. The ostensible goal of such schools was to teach Indian children the skills necessary to function effectively in American society. But in the name of uplift, civilization, and assimilation, these schools took Indian children away from their families and tribes and sought to strip them of their cultural heritage.

By the late nineteenth century, there was a widespread sense that the removal and reservation policies had failed. No one did a more effective job of arousing public sentiment about the Indians’ plight than Helen Hunt Jackson, a Massachusetts-born novelist and poet. Her classic book A Century of Dishonor (1881), recorded the country’s sordid record of broken treaty obligations, and did as much to stimulate public concern over the condition of Indians as Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin did to raise public sentiment against slavery or Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring did to ignite outrage against environmental exploitation. Ironically, reformers believed that the solution to the “Indian problem” was to erase a distinctive Indian identity.

During the late nineteenth century, humanitarian reformers repeatedly called for the government to support schools to teach Indian children “the white man’s way of life,” end corruption on Indian reservations, and eradicate tribal organizations. The federal government partly adopted the reformers’ agenda. Many reformers denounced corruption in the Indian Bureau, which had been set up in 1824 to provide assistance to Indians. In 1869, one member of the House of Representatives said, “No branch of the federal government is so spotted with fraud, so tainted with corruption…as this Indian Bureau.” To end corruption, Congress established the Board of Indian Commissioners in 1869, which had the major Protestant religious denominations appoint agents to run Indian reservations. The agents were to educate and Christianize the Indians and teach them to farm. Dissatisfaction with bickering among church groups and the inexperience of church agents led the federal government to replace church-appointed Indian agents with federally-appointed agents during the 1880s.

In 1871 to weaken the authority of tribal leaders, Congress ended the practice of treating tribes as sovereign nations. To undermine older systems of tribal justice, Congress, in 1882, created a Court of Indian Offenses to try Indians who violated government laws and rules.

One of history’s greatest challenges is to understand acts of historical evil: how people as intelligent and moral as we are could commit unspeakable acts of violence and cruelty.

There is a word that helps describe U.S. policy toward Native Americans at the end of the nineteenth century. It is ethnocide—the deliberate, systematic effort to suppress or destroy a culture. It involves eliminating a people’s language, customs, and cultural and religious practices.

The term ethnocide was coined in 1944 by a Polish born lawyer, Raphael Lemkin, the same year that he coined the word genocide, the intentional murder of an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group.

Native Americans at the Turn of the Century

As the nineteenth century ended, Native Americans seemed to be a disappearing people. The 1890 census recorded an Indian population of less than 225,000, and falling. The prevailing view among whites was that Indians should be absorbed as rapidly as possible into the dominant society: their reservations broken up, tribal authority abolished, traditional religions and languages eradicated. Late nineteenth century federal policy embodied this attitude. In 1871 Congress declared that tribes were no longer separate, independent governments. It placed tribes under the guardianship of the federal government. The 1887 Dawes Act allotted reservation lands to individual Indians in units of 40 to 160 acres. Land that remained after allotment was to be sold to whites to pay for Indian education.

The Dawes Act was supposed to encourage Indians to become farmers. But most of the allotted lands proved unsuitable for farming, owing to a lack of sufficient rainfall. The plots were also too small to support livestock.

Much Indian land quickly fell into the hands of whites. There was to be a twenty-five-year trust period to keep Indians from selling their land allotments, but an 1891 amendment did allow Indians to lease them, and a 1907 law let them sell portions of their property. A policy of “forced patents” took additional lands out of Indian hands. Under this policy, begun in 1909, government agents determined which Indians were “competent” to assume full responsibility for their allotments.

Many of these Indians quickly sold their lands to white purchasers. Altogether, the severalty policy reduced Indian-owned lands from 155 million acres in 1881 to 77 million in 1900 and just 48 million acres in 1934. The most dramatic loss of Indian land and natural resources took place in Oklahoma. At the end of the nineteenth century, the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Creek nations held half the territory’s land. But by 1907, when Oklahoma became a state, much of this land, as well as its valuable asphalt, coal, natural gas, and oil resources, had passed into the possession of whites.