Wounded Knee

The Ghost Dance

The late nineteenth century marked the nadir of Indian life. Deprived of their homelands, their revolts suppressed, and their way of life besieged, many Plains Indians dreamed of restoring a vanished past, free of hunger, disease, and bitter warfare. The 6,000 Sioux at the Pine Ridge Reservation had seen their beef rations severely reduced. They had once subsisted on buffalo; now fewer than 2,000 of these animals populated the Plains.

Beginning in the 1870s, a religious movement known as the Ghost Dance arose among Indians of the Great Basin, and then spread, in the late 1880s, to the Great Plains. Beginning among the Paiute Indians of Nevada in 1870, the Ghost Dance promised to restore the way of life of their ancestors.

Around 1870, in Nevada, a Paiute named Tavibo declared he had a vision of Christ’s Second Coming. He said he was told to teach the Indians to prepare by doing good works and engaging in a ritual dance. With this dance, his people would be reunited with their ancestors in the spirit world.

During the late 1880s, the ghost religion was revived and had great appeal among the Sioux, despairing over the death of a third of their cattle by disease and angry that the federal government had cut their food rations. In 1889, Wovoka, a Paiute holy man from Nevada, had a revelation. If only the Sioux would perform sacred dances and religious rites, then the Great Spirit would return and raise the dead, restore the buffalo to life, and cause a flood that would destroy the whites.

Wearing special Ghost Dance shirts, fabricated from white muslin and decorated with red fringes and painted symbols, dancers would spin in a circle until they became so dizzy that they entered into a trance.

Among many peoples experiencing social dislocation, religious movements, known as millennarian movements, arise, giving expression to a desire to restore traditional ways of life.

White settlers became alarmed. Said one: “Indians are dancing in the snow and are wild and crazy…We need protection, and we need it now.”

The Wounded Knee Massacre

Fearful that the Ghost Dance would lead to a Sioux uprising, army officials ordered Indian police to arrest 38 Indian leaders, including the Sioux spiritual leader Sitting Bull. During Sitting Bull’s arrest, he, his fourteen-year-old son, and six of his followers were killed, along with six of the arresting officers. The reservation police claimed that Sitting Bull had resisted arrest.

Alarmed by Sitting Bull’s death, many Sioux fled to Pine Ridge in southwestern South Dakota. They were pursued by U.S. forces including units of the Seventh Cavalry, the regiment that Sitting Bull and Crazy horse had defeated at the battle of the Little Big Horn, and the Indian leader Big Foot, suffering from pneumonia and internal bleeding, ran up a white flag. The cavalrymen escorted the party, 120 men and 230 women and children, to Wounded Knee Creek.

The next morning, December 29, the Indians were told to give up their arms. A gun went off. The soldiers opened fire with Hotchkiss guns, which could fire fifty rounds a minute, and other weapons. The shooting lasted about ten minutes, and at least 146 Indian men, women, and children were left dead. Some historians believe the actual number of Indians killed was over 200..

The dead Indians’ bodies were taken from the snow and buried in mass graves. U.S. forces received twenty-two Congressional Medals of Honor for their actions at Wounded Knee.

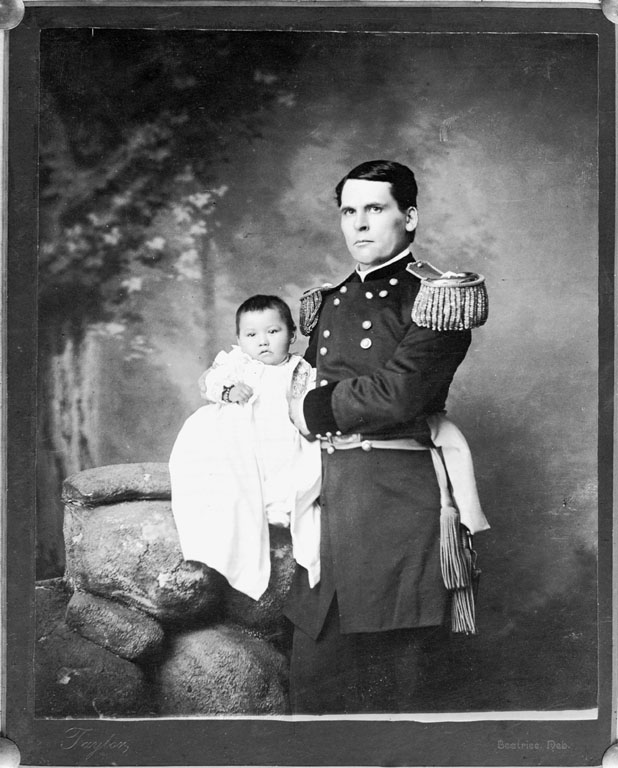

Four men and 47 women and children, many of whom were wounded, were taken away alive, including a Lakota infant lying beneath her mother’s body, named Zintkala Nuni or Lost Bird. Just four months old, she had been protected from the soldiers’ bullets by her mother’s body. The child was raised by Brigadier General Leonard Colby and his wife Clara, who renamed her Marguerite. For a time, she worked in Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show and died at the age of 29.

General Nelson Miles, who commanded military forces in the area, sought a court martial for the office in charge of the troops at Wounded Knee. Miles described what happened as a “cruel and unjustifiable massacre.”

The Oglala Sioux spiritual leader Black Elk summed up the meaning of Wounded Knee: “I can see that something else died there in the bloody mud, and was buried in the blizzard. A people’s dream died there.”

The Battle of Wounded Knee marked the end of three centuries of bitter warfare between Indians and whites. Indians had been confined to small reservations, where reformers would seek to transform them into Christian farmers. In the future, the Indian struggle to maintain an independent way of life and a separate culture would take place on new kinds of battlefields.

While serving as the editor and publisher of the Aberdeen, South Dakota Saturday Pioneer, L. Frank Baum, the author of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, wrote an editorial following the death of Sitting Bull. “The Whites, by law of conquest, by justice of civilization, are masters of the American continent,” he wrote, “and the best safety of the frontier settlers will be secured by the total annihilation of the few remaining Indians.”

The West, it is said, was not won. It was stolen. This is a succinct and not inaccurate summary of Indian-white relations. Whites coveted Native American lands and seized most of it and quashed Indian resistance with violence.