The First Bush Presidency

The First Bush Presidency

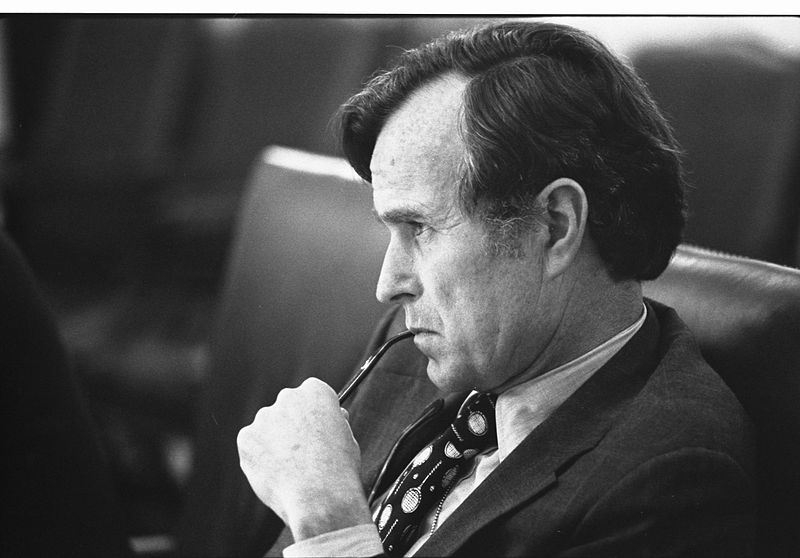

In the 1988 presidential campaign, the Republican candidate, Vice President George Bush, was said to have the best resume in Washington. Bush won the Distinguished Service Cross during World War II, made a fortune in the Texas oil business, and then went to Washington where he served as a Congressman, ambassador to the United Nations, envoy to China, and director of the CIA. His Democratic opponent, Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis, was a serious, hardworking son of Greek immigrants.

Mudslinging and personal invective are nothing new in American politics, but the 1988 campaign was unusually vacuous and cynical. Real differences between the candidates were submerged in a battle over character, abortion, prison furloughs, school prayer, and patriotism. The campaign dramatized a development that had been reshaping American politics since the late 1960s: the growing power of media consultants and pollsters, who marketed candidates by emphasizing imagery and symbolism. At the end of a race that saw both candidates use negative campaigning, Bush was elected the 41st president of the United States with 56 percent of the popular vote.

A Kinder, Gentler Nation

In his inaugural address, Bush signaled a departure from the avarice and greed of the Reagan era by calling for a “new engagement in the lives of others.” He promised to be more of a “hands on” administrator than his predecessor, and he committed his presidency to creating a “kinder, gentler” nation, more sensitive and caring to the poor and disadvantaged.

During his first years in office, President Bush and the Democratic-controlled Congress addressed many issues ignored during the Reagan years. For the first time in eight years, the minimum wage was raised from $3.35 to $4.25 an hour. Congress amended federal air pollution laws in order to reduce noxious emissions and acid rain. For the first time since 1971, Congress considered child-care legislation, and ultimately, voted to provide subsidies to low-income families to defray the costs of childcare. In other actions, Congress prohibited job discrimination against the disabled, required nutrition labeling on processed foods, and expanded immigration into the United States.

In two areas, critics accused President Bush of reneging on his promise of a “kinder, gentler” nation. He vetoed a new civil rights bill bolstering protections for minorities and women against job discrimination on the grounds that it would lead to quotas. Bush also vetoed a bill that would have provided up to six months of unpaid family leave for workers with newly born or adopted children or for emergencies. In November 1991, however, Bush signed a compromise, the Civil Rights Act, which made it easier for workers to win anti-discrimination lawsuits.

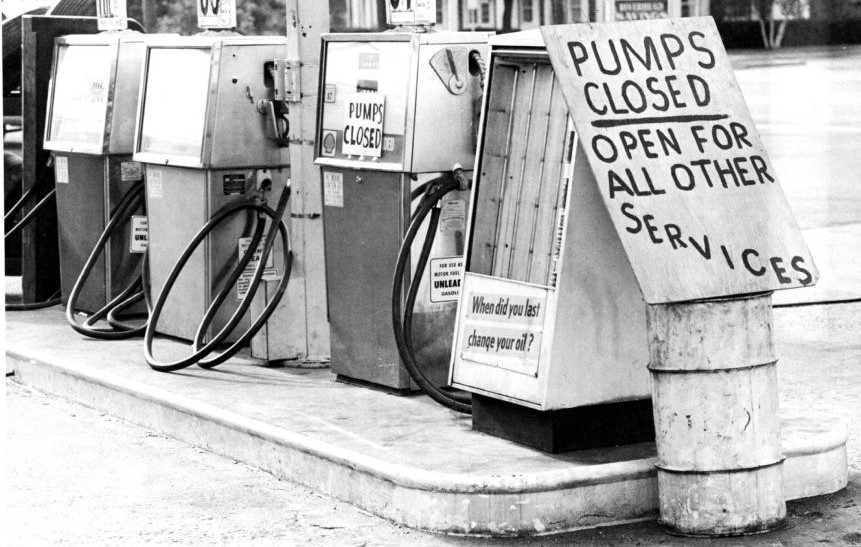

Economic Policy

Many Americans believed that the end of the Cold War would bring a huge peace dividend, which could be used to reduce the federal budget deficit and fund domestic social programs. Soon after Bush took office, however, Americans learned that much of the peace dividend would have to be spent to clean up nuclear wastes produced at federal facilities and to bail out the nation’s troubled savings and loan industry.

The roots of the savings and loan crisis were planted during the presidency of Jimmy Carter. High inflation and high interest rates threatened to bankrupt those savings institutions that could not compete with other financial institutions permitted to pay high interest rates. A 1980 law lifted limits on the interest rates that savings institutions could pay and allowed them to make a limited amount of investments in commercial real estate. In 1982 and 1983, Congress broadened the banking industry’s capacity to make unsecured commercial loans and investments in commercial real estate.

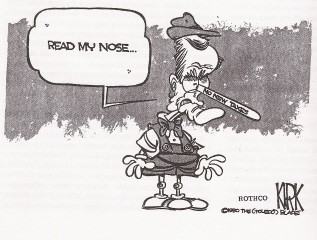

The savings and loan industry’s problems began in the mid-1980s. Falling oil prices led to a collapse of land values, especially in the Southwest, creating huge losses for institutions that had invested in real estate. By the end of the decade, these institutions began to fail in large numbers. The mounting bills for the savings and loan bailout propelled President Bush in 1990 to violate his 1988 “no new taxes” campaign pledge.

Foreign Policy

The first important foreign policy act of the Bush administration was an invasion of Panama, which the Pentagon called “Operation Just Cause”. The origins of the conflict stretched back to 1987 when a high Panamanian military official accused strongman General Manuel Antonio Noriega of committing fraud in the 1984 presidential election and of drug trafficking.

Violent street demonstrations broke out in Panama as angry Panamanians called for Noriega’s overthrow. Noriega responded by declaring a state of emergency. The crisis escalated when two Florida grand juries indicted the general on charges that he protected and assisted the Colombian drug cartel.

U.S.-Panamanian relations deteriorated further when Noriega voided results of the 1989 presidential election and sent paramilitary forces into the streets of Panama City, where they beat up opposition candidates. Conflict grew imminent when Noriega declared his country in a “state of war” against the United States. A day later, four unarmed American military personnel were fired on at a roadblock by Panamanian troops, and one American was killed. Bush dispatched a force of 10,000 troops to safeguard the lives of Americans and to protect the integrity of the Panama Canal treaties. Between 300 and 800 Panamanian civilians and military personnel died during the invasion. There were 23 American casualties. Noriega was forced out of power and deported to the United States to stand trial for drug trafficking.

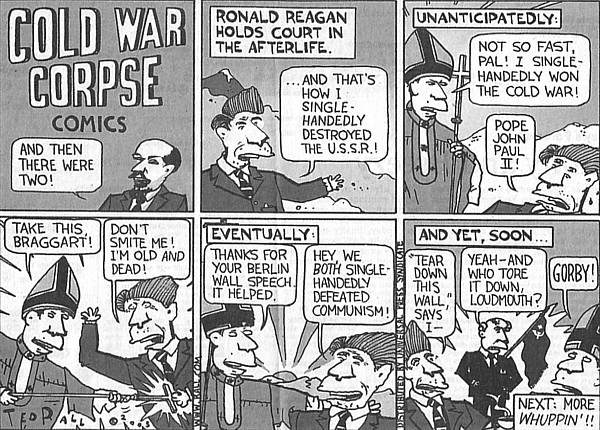

Collapse of Communism

For forty years, Communist Party leaders in Eastern Europe had ruled confidently. Each year their countries fell further behind the West. Yet, they remained secure in the knowledge that the Soviet Union, backed by the Red Army, would always send in the tanks when the forces for change became too great. But they had not bargained on a liberal Soviet leader like Mikhail Gorbachev.

As Gorbachev moved toward reform within the Soviet Union and détente with the West, he pushed the conservative regimes of Eastern Europe outside his protective umbrella. By the end of 1989, the Berlin Wall had been smashed. All across Eastern Europe, citizens took to the streets, overthrowing forty years of Communist rule. Like a series of falling dominos, Communist parties in Poland, East Germany, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Bulgaria fell from power.

Gorbachev, who had wanted to reform communism, may not have anticipated the swift swing toward democracy in Eastern Europe. Nor had he fully foreseen the impact that democracy in Eastern Europe would have on the Soviet Union. By 1990, leaders of several Soviet republics began to demand independence or greater autonomy within the Soviet Union.

Gorbachev had to balance the growing demand for radical political change within the Soviet Union with the demand by Communist hardliners. The hardliners demanded that he contain the new democratic currents and turn back the clock. Faced with dangerous political opposition from the right and the left and with economic failure throughout the Soviet Union, Gorbachev tried to satisfy everyone and, in the process, satisfied no one.

In 1990, following the example of Eastern Europe, the three Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia announced their independence, and other Soviet republics demanded greater sovereignty. Nine of the fifteen Soviet republics agreed to sign a new union treaty, granting far greater freedom and autonomy to individual republics.

But in August 1991, before the treaty could be signed, conservative Communists tried to oust Gorbachev in a coup d’état. Boris Yeltsin, the President of the Russian Republic, and his supporters defeated the coup, undermining support for the Communist Party. Gorbachev fell from power. The Soviet Union ended its existence in December 1991, when Russia and most other republics formed the Commonwealth of Independent States.

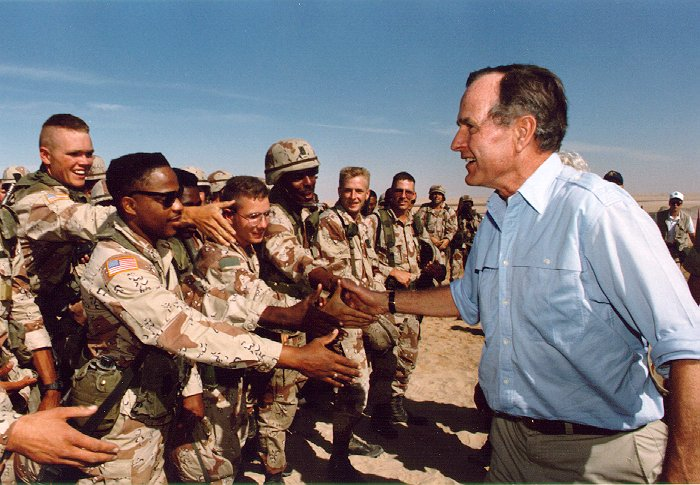

The Persian Gulf War

At 2 a.m., August 2, 1990, some 80,000 Iraqi troops invaded and occupied Kuwait, a small, oil-rich emirate on the Persian Gulf. This event touched off the first major international crisis of the post-Cold War era. Iraq’s leader, Saddam Hussein, justified the invasion on the grounds that Kuwait, which he accused of intentionally depressing world oil prices, was a historic part of Iraq.

Iraq’s invasion caught the United States off guard. The Hussein regime was a brutal military dictatorship that ruled by secret police and used poison gas against Iranians, Kurds, and Shiite Muslims. During the 1970s and 1980s, the United States—and Britain, France, the Soviet Union, and West Germany—sold Iraq an awesome arsenal that included missiles, tanks, and the equipment needed to produce biological, chemical, and nuclear weapons. During Baghdad’s eight-year-long war with Iran, the United States, which opposed the growth of Muslim fundamentalist extremism, tilted toward Iraq.

On August 6, 1990, President Bush dramatically declared, “This aggression will not stand.” With Iraqi forces poised near the Saudi Arabian border, the Bush administration dispatched 180,000 troops to protect the Saudi kingdom. In a sharp departure from American foreign policy during the Reagan presidency, Bush also organized an international coalition against Iraq. He convinced Turkey and Syria to close Iraqi oil pipelines, won Soviet support for an arms embargo, and established a multi-national army to protect Saudi Arabia. In the United Nations, the administration succeeded in persuading the Security Council to adopt a series of resolutions condemning the Iraqi invasion, demanding restoration of the Kuwaiti government, and imposing an economic blockade.

Bush’s decision to resist Iraqi aggression reflected the president’s assessment of vital national interests. Iraq’s invasion gave Saddam Hussein direct control over a significant portion of the world’s oil supply. It disrupted the Middle East balance of power and placed Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf emirates in jeopardy. Iraq’s 545,000-man army threatened the security of such valuable U.S. allies as Egypt and Israel.

In November 1990, the crisis took a dramatic turn. President Bush doubled the size of American forces deployed in the Persian Gulf, a sign that the administration was prepared to eject Iraq from Kuwait by force. The president went to the United Nations for a resolution permitting the use of force against Iraq if it did not withdraw by January 15, 1991. After a heated debate, Congress also gave the president authority to wage war.

President Bush’s decision to liberate Kuwait was an enormous political and military gamble. The Iraqi army, the world’s fourth largest, was equipped with Exocet missiles, top-of-the-line Soviet T-72 tanks, and long-range artillery capable of firing nerve gas. But after a month of allied bombing, the coalition forces had achieved air supremacy; had destroyed thousands of Iraqi tanks and artillery pieces, supply routes and communications lines, and command-and-control bunkers; plus, had limited Iraq’s ability to produce nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons. Iraqi troop morale suffered so badly under the bombing that an estimated 30 percent of Baghdad’s forces deserted before the ground campaign started.

The allied ground campaign relied on deception, mobility, and overwhelming air superiority to defeat the larger Iraqi army. The allied strategy was to mislead the Iraqis into believing that the allied attack would occur along the Kuwaiti coastline and Kuwait’s border with Saudi Arabia. Meanwhile, General H. Norman Schwarzkopf, American commander of the coalition forces, shifted more than 300,000 American, British, and French troops into western Saudi Arabia, allowing them to strike deep into Iraq. Only 100 hours after the ground campaign started, the war ended. Saddam Hussein remained in power, but his ability to control events in the region was dramatically curtailed. The Persian Gulf conflict was the most popular U.S. war since World War II. It restored American confidence in its position as the world’s sole superpower and helped to exorcise the ghost of Vietnam that had haunted American foreign policy debates for nearly two decades. The doubt, drift, and demoralization that began with the Vietnam War and the Watergate scandal appeared to have ended.

[The word bubble says, “Read my nose.” His nose reads, “No new taxes.”]