The Reagan Revolution

The Reagan Revolution

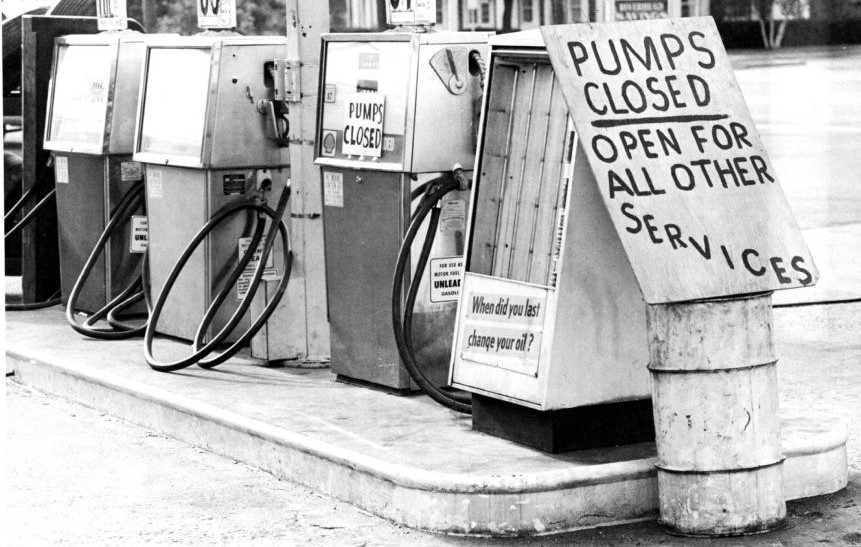

The traumatic events of the 1970s—Watergate, stagflation, the energy crisis, the decline of American industry, the defeat of South Vietnam, and the Iranian hostage crisis—produced a severe loss of confidence among the American people. Americans were deeply troubled by the relative loss of American strength in the world, the decline of productivity and innovation in American industry, and the dramatic growth of lobbies and special-interest groups that seemed to have paralyzed the legislative process. Many worried that too much power had been stripped from the presidency and that political parties were so weakened and Congress so splintered, that it was impossible to enact a coherent legislative program.

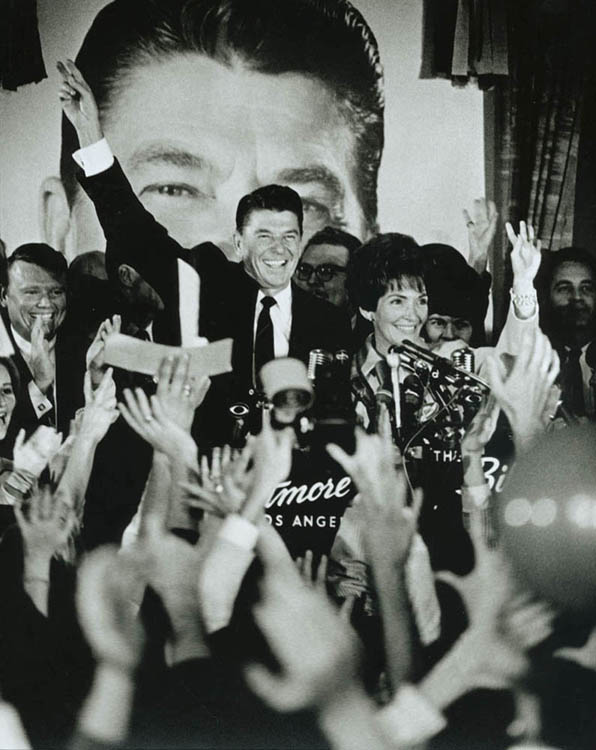

Ronald Reagan capitalized on the public’s frustration. When he ran for the presidency against Carter in 1980, he asked Americans, “Are you better off than you were four years ago?” With annual inflation at eighteen percent, the answer was a resounding “No.” Reagan won a landslide victory, carrying 43 states and almost 51 percent of the popular vote compared to Carter’s 41 percent. In addition, the Democrats lost the Senate for the first time since 1954.

The Gipper

When he was elected president in 1980, Ronald Reagan was already well known to the American people as a movie actor and television announcer. He had risen to celebrity status from extremely modest beginnings. Born in 1911, Reagan, the son of a shoe salesman, grew up in a succession of small Illinois towns. After a stint as a sportscaster at a radio station in Des Moines, Iowa, Reagan landed a Hollywood screen test in 1937. He went on to make fifty films, most of them B movies. Reagan is often remembered for his performance in Knute Rockne, All American (1940). He played George Gipp, the Notre Dame halfback, whose dying words were, “Win one for the gipper.” After World War II he served as president of the Screen Actors Guild, and in 1954 he turned to television, hosting “GE Theater” and “Death Valley Days.”

In politics Reagan started out as a liberal staunchly supporting Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. As head of the Screen Actors Guild, however, he became concerned about Communist infiltration of the labor movement in Hollywood. Reagan was catapulted into the national political spotlight in 1964 when he gave an emotional speech in support of Republican nominee Barry Goldwater: denouncing big government, foreign aid, welfare, urban renewal, and high taxes. Two years later, he successfully ran for governor of California, promising to cut state spending and crack down on student protesters.

In the 1980 presidential campaign, Reagan drew strong support from white Southerners, suburban Roman Catholics, evangelical Christians, and particularly, the New Right. The New Right was a confederation of disparate political and religious groups bound together by their concern over what they believed were the erosion of values in America.

Reaganomics

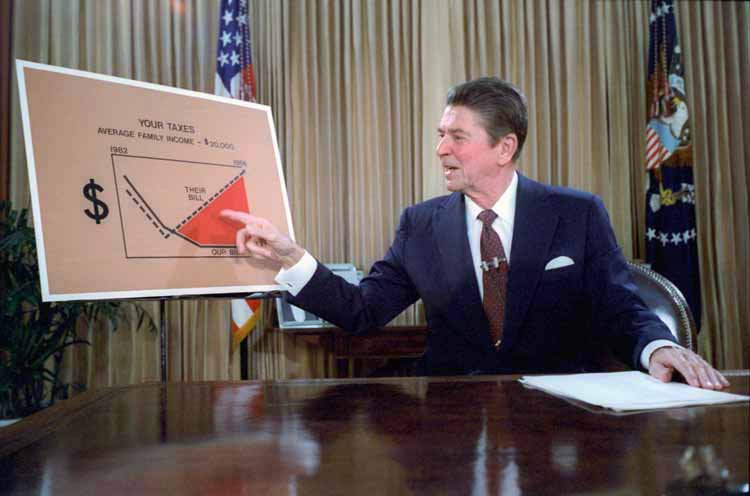

When President Reagan took office, he promised to rebuild the nation’s defenses, restore economic growth, and trim the size of the federal government by limiting its role in welfare, education, and housing. He pledged to end exorbitant union contracts to make American goods competitive again, to cut taxes drastically to stimulate investment and purchasing power, and to decontrol businesses strangled by federal regulation. Even though his policies trimmed little from the size of the federal government, failed to make American goods competitive in the world market, and led to increased consolidation rather than competition, many Americans believed that he had improved the country’s economic situation.

Reagan blamed the nation’s economic ills on declining capital investment and a tax structure biased against work and productive investment. To stimulate the economy, he persuaded Congress to slash tax rates. In 1981, he pushed a bill through Congress cutting taxes five percent in 1981 and ten percent in 1982 and 1983. In 1986, the administration pushed through another tax bill, which substantially reduced tax rates of the wealthiest Americans to 28 percent, while closing a variety of tax loopholes.

In August 1981, Reagan dealt a devastating blow to organized labor by firing 15,000 striking air-traffic controllers after they went on strike and refused a directive to return to work. Union leaders condemned the firings, but in an anti-union atmosphere, most Americans backed Reagan. His popularity ratings soared.

To strengthen the nation’s defenses, the Reagan administration doubled the defense budget—to more than $330 billion by 1987. Reagan believed that a militarily strong America would not have been humiliated by Iran and would have discouraged Soviet adventurism.

Reagan expanded the Carter administration’s efforts to decontrol and deregulate the economy. Congress deregulated the banking and natural gas industries and lifted ceilings on interest rates. Federal price controls on airfares were lifted as well. The Environmental Protection Agency relaxed its interpretation of the Clean Air Act; and the Department of the Interior opened up large areas of the federal domain, including offshore oil fields, to private development.

The results of deregulation were mixed. Bank interest rates became more competitive, but smaller banks found it difficult to hold their own against larger institutions. Natural gas prices increased, as did production, easing some of the country’s dependence on foreign fuel. Airfares on high-traffic routes between major cities dropped dramatically, but fares for short, low-traffic flights skyrocketed. Most critics agreed, however, that deregulation had restored some short-term competition to the marketplace. Yet in the long-term, competition also led to increased business failures and consolidation.

Reagan’s laissez-faire principles could also be seen in his administration’s approach to social programs. Convinced that federal welfare programs promoted laziness, promiscuity, and moral decay, Reagan limited benefits to those he considered the “truly needy.” His administration cut spending on a variety of social welfare programs, including Aid to Families with Dependent Children, food stamps, child nutrition, job training for young people, programs to prevent child abuse, and mental health services. The Reagan administration also eliminated welfare assistance for the working poor and reduced federal subsidies for child-care services for low-income families. Symbolic of the Reagan social service cuts, an attempt was made by the Agriculture Department in 1981 to allow ketchup to be counted as a vegetable in school lunches.

Reagan left office while the economy was in the midst of its longest post-World War II expansion. The economy was growing faster, with less inflation, than at any time since the mid-1960s. Adjusted for inflation, disposable personal income per person rose twenty percent after 1980. Inflation fell from thirteen percent in 1981 to less than four percent annually. Unemployment was down to approximately five percent.

Critics, however, charged that Reagan had only created the illusion of prosperity. They denounced the massive federal budget deficit, which increased $1.5 trillion during the Reagan presidency—a deficit that was three times the debt accumulated by all 39 of Reagan’s presidential predecessors. His critics decried the growing income gap between rich and poor. They also criticized the expensive consequences of reduced government regulation, namely, cleaning up federal nuclear weapons facilities, and especially, bailing out the nation’s savings and loans industry. But there could be little doubt that President Reagan had restored the nation’s self-confidence and faith in the federal government and made conservatism a strong political force.

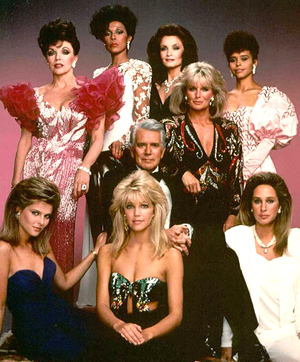

The Celebration of Wealth

In 1981, the year Ronald Reagan was inaugurated as president, ABC television introduced the smash hit “Dynasty,” a show celebrating glamour and greed. It was, in the eyes of many social commentators, an appropriate beginning for the 1980s—a decade of selfishness and an anything goes attitude.

Wall Street enthusiastically took part in the new celebration of wealth, as the Reagan years witnessed a corporate merger and takeover boom of unprecedented proportions. By using low-grade, risky “junk bonds” to finance corporate acquisitions, corporate raiders, such as Michael Milken of Drexel Burnham Lambert purchased and then dismantled companies for huge profits. In 1987, Milken earned $550 million by financing acquisitions.

During the 1980s, 100,000 Americans became millionaires every year. The average annual earnings of the bottom twenty percent, however, fell from $9,376 to $8,800. In addition, many of the new jobs created during the Reagan years were in the low-wage service industries.

By the early 1990s, there were signs that the time had come to pay for the financial excesses of the 1980s. On October 19, 1987, the Dow Jones industrial average fell 508 points—a 22.6 percent plunge in stocks in one day. In response, many Wall Street stock brokerage firms began to lay off employees—cutbacks that continued despite the market’s recovery. In 1989, Milken was indicted on charges of criminal racketeering and securities fraud. The next year, Drexel Burnham Lambert agreed to pay a fine of $650 million and filed for bankruptcy. Wall Street speculator Ivan Boesky was fined $100 million for insider trading and sentenced to jail. Those Americans who had fostered in the ambition, greed, and excesses of the 1980s seemed to be getting their comeuppance.

The Reagan Doctrine

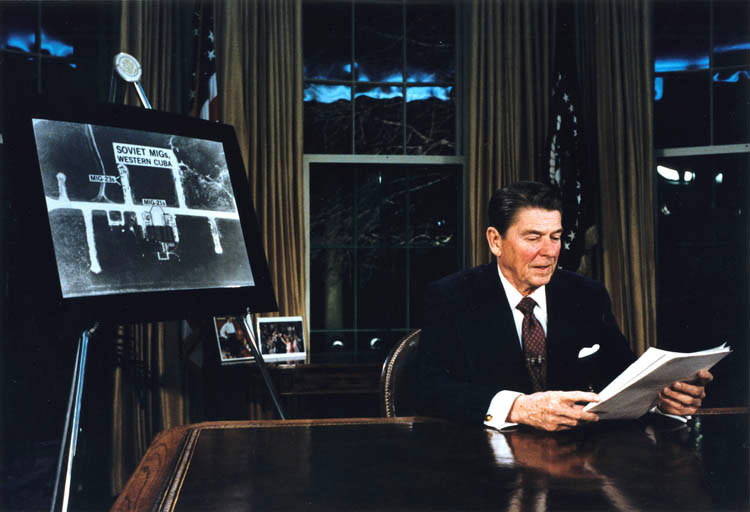

During the early years of the Reagan presidency, Cold War tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States intensified. Reagan entered office deeply suspicious of the Soviet Union. Reagan described the Soviet Union as “an evil empire” and called for a space-based missile defense system, derided by critics as “Star Wars.”

Reagan and his advisers tended to view every regional conflict through a Cold War lens. Nowhere was this truer than in the Western Hemisphere, where he was determined to prevent Communist takeovers. In October 1983, Prime Minister Maurice Bishop of Grenada, a small island nation in the Caribbean, was assassinated and a more radical Marxist government took power. Afterwards, Soviet money and Cuban troops came to Grenada. When they began constructing an airfield capable of landing large military aircraft, the Reagan administration decided to remove the Communists and restore a pro-American regime. On October 25, U.S. troops invaded Grenada, killed or captured 750 Cuban soldiers, and established a new government. The invasion sent a clear message throughout the region that the Reagan administration would not tolerate Communism in its hemisphere.

In his 1985 state of the union address, President Reagan pledged his support for anti-Communist revolutions in what would become known as the “Reagan Doctrine.” In Afghanistan, the United States was already providing aid to anti-Soviet freedom fighters, ultimately, helping to force Soviet troops to withdraw. It was in Nicaragua, however, that the doctrine received its most controversial application.

In 1979, Nicaraguans revolted against the corrupt Somoza regime. A new junta took power dominated by young Marxists known as Sandinistas. The Sandinistas insisted that they favored free elections, non-alignment, and a mixed economy, but once in power, they postponed elections, forced opposition leaders into exile, and turned to the Soviet bloc for arms and advisers. For the Reagan administration, Nicaragua looked “like another Cuba,” a Communist state that threatened the security of its Central American neighbors.

In his first months in office, President Reagan approved covert training of anti-Sandinista rebels called “contras”. While the contras waged war on the Sandinistas from camps in Honduras, the CIA provided assistance. In 1984, Congress ordered an end to all covert aid to the contras.

The Reagan administration circumvented Congress by soliciting contributions for the contras from private individuals and from foreign governments seeking U.S. favor. The president also permitted the sale of arms to Iran, with profits diverted to the contras. The arms sale and transfer of funds to the contras were handled surreptitiously through the CIA intelligence network, apparently with the full support of CIA Director William Casey. Exposure of the Iran-Contra affair in late 1986 provoked a major congressional investigation. The scandal seriously weakened the influence of the president. The American preoccupation with Nicaragua began to subside in 1987, after President Oscar Arias Sanches of Costa Rica proposed a regional peace plan. In national elections in 1990, the Nicaraguan opposition routed the Sandinistas, bringing an end to ten turbulent years of Sandinista rule.

A Remarkable Ideological Turnaround

In 1982, 75-year-old Soviet party leader, Leonid Brezhnev, died. Growing stagnation, corruption, and a huge military buildup had marked his regime. Initially, the post-Brezhnev era seemed to offer little change in U.S.-Soviet relations. KGB leader, Yuri Andropov, succeeded Brezhnev, but died after only fifteen months in power. Another Brezhnev loyalist, Konstantin Chernenko, who died just a year later, replaced him. In 1985, Soviet party leadership passed to Mikhail S. Gorbachev, a 54-year-old agricultural specialist with little formal experience in foreign affairs. Gorbachev pledged to continue the policies of his predecessors.

Within weeks, however, Gorbachev called for sweeping political liberalization (glasnost) and economic reform (perestroika). He allowed wider freedom of press, assembly, travel, and religion. He persuaded the Communist party leadership to end its monopoly on power, created the Soviet Union’s first working legislature, allowed the first nationwide competitive elections in 1989, and freed hundreds of political prisoners. In an effort to boost the sagging Soviet economy, he legalized small private business cooperatives, relaxed laws prohibiting land ownership, and approved foreign investment within the Soviet Union.

In foreign affairs, Gorbachev completely reshaped world politics. He cut the Soviet defense budget, withdrew Soviet troops from Afghanistan and Eastern Europe, allowed a unified Germany to become a member of NATO, and agreed with the United States to destroy short-range and medium-range nuclear weapons. Most dramatically, Gorbachev actively promoted the democratization of former satellite nations in Eastern Europe and withdrawing Soviet forces from the region (as well as from Afghanistan). For his accomplishments in defusing Cold War tensions, he was awarded the 1990 Nobel Peace Prize.

The Reagan Revolution in Perspective

In the presidential election of 1984, Ronald Reagan and Vice President George Bush won in a landslide over Walter Mondale and Geraldine Ferraro. Ferraro was the first woman nominated for vice president on a major party ticket. Although Reagan’s second term was plagued by the Iran-Contra scandal, he left office after eight years more popular than when he arrived. He could claim the distinction of being the first president to serve two full terms since Dwight Eisenhower.

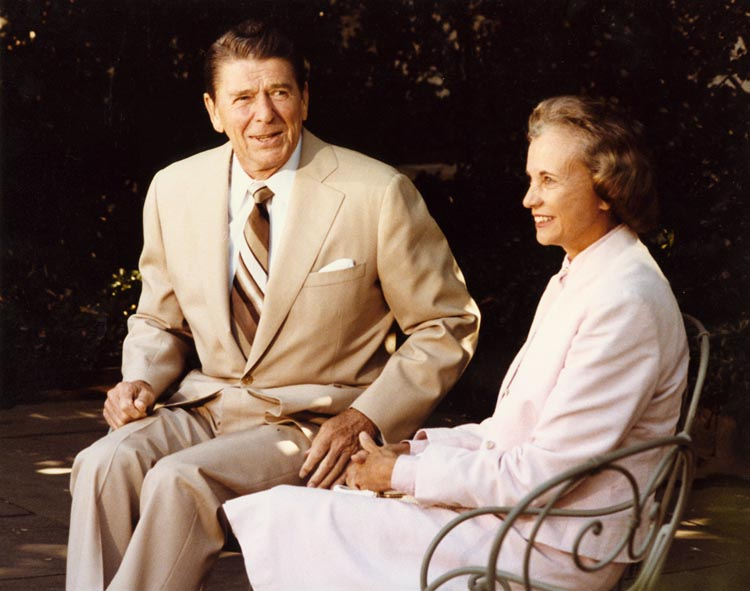

Ronald Reagan could also point to an extraordinary string of accomplishments. He dampened inflation, restored public confidence in government, and presided over the beginning of the end of the Cold War. He doubled the defense budget, named the first woman to the Supreme Court, launched a strong economic boom, and created a heightened sense of national unity. In addition, his supporters said that he restored vigor to the national economy and psyche, rebuilt America’s military might, regained the nation’s place as the world’s preeminent power, restored American patriotism, and championed traditional family values.

On the other hand, his detractors criticized him for a reckless use of military power and for circumventing Congress in foreign affairs. They accused Reagan of fostering greed and intolerance. His critics also charged that his administration, in its zeal to cut waste from government, ripped the social safety net and skimped on the government’s regulatory functions. The administration, they further charged, was insensitive on racial issues.

Reagan’s detractors were particularly concerned about his economic legacy. During the Reagan years, the national debt tripled, from $909 billion to almost $2.9 trillion. The interest alone amounted to 14 percent of the federal budget. The deficit soaked up savings, caused interest rates to rise, and forced the federal government to shift more and more responsibilities onto the states. Corporate and individual debt also soared. During the early 1990s, the American people consumed $1 trillion more goods and services than they produced. The United States also became the world’s biggest debtor nation, as a result of a weak dollar, a low level of exports, and the need to borrow abroad to finance budget deficits.

As President, Ronald Regan re-defined and re-directed the national agenda and geopolitics. He made conservatism, once regarded as a marginal movement, into the dominant force in American politics at least until 2008.