A New American Role in the World

A New American Role in the World

In his inaugural address in 1961, John Kennedy stated that America would “pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, or oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty.” But by 1973, in the wake of the Vietnam War, American foreign policymakers regarded Kennedy’s stirring pledge as unrealistic. The Vietnam War offered a lesson about the limits of American power. It underscored the need to distinguish between vital national interests and peripheral interests and to balance America’s military commitments with its available resources. Above all, the Vietnam War appeared to illustrate the dangers of obsessive anti-Communism. Such a policy failed to recognize that the world was becoming more complex, that power blocs were shifting, and that the interests of Communist countries and the United States could sometimes overlap. Too often, American policy seemed to have driven nationalists and reformers into Communist hands and led the United States to support corrupt, unpopular, authoritarian regimes. The great challenge facing American foreign policymakers was how to preserve the nation’s international prestige and influence in the face of declining defense budgets and mounting congressional opposition to direct overseas intervention.

Détente

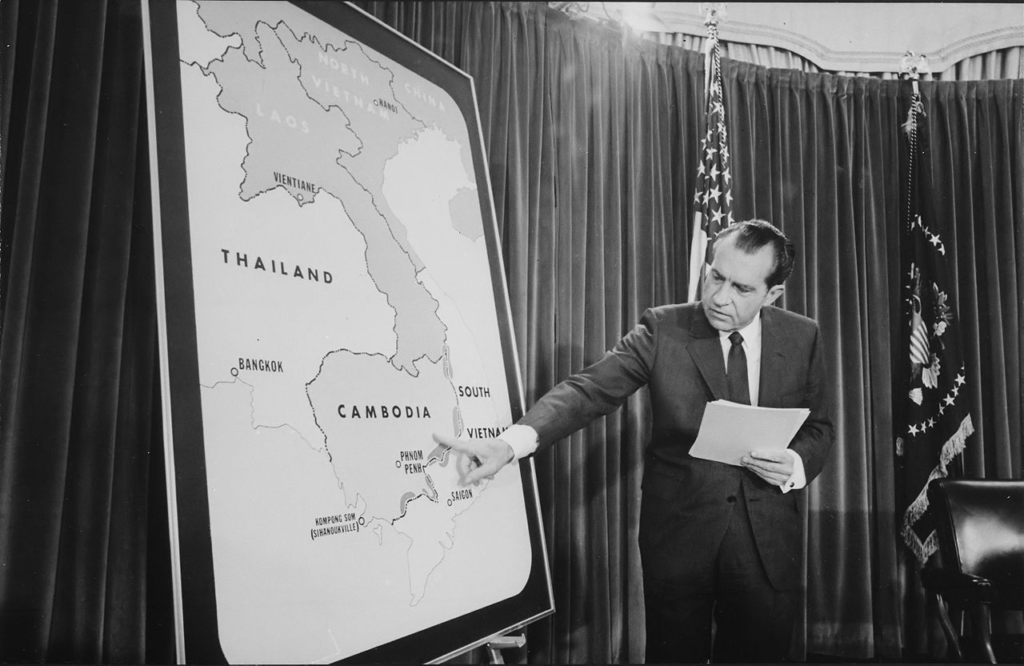

As president, Richard Nixon radically redefined America’s relationship with its two foremost adversaries, China and the Soviet Union. In a remarkable turnabout from his record of staunch anti-Communism, Nixon opened relations with China and began strategic arms limitation talks with the Soviet Union. The goal of détente (the easing of tensions between nations) was to continue to resist and deter Soviet adventurism while striving for “more constructive relations” with the Communist world.

Richard Nixon and his National Security Adviser (and later Secretary of State) Henry Kissinger believed that it was necessary to curb the arms race, improve great-power relationships, and learn to coexist with Communist regimes. The Nixon administration sought to use the Chinese and Soviet need for Western trade and technology as a way to extract foreign policy concessions.

Recognizing that one of the legacies of Vietnam was reluctance on the part of the American public to risk overseas interventions, Nixon and Kissinger also sought to build up regional powers that shared American strategic interests, most notably China, Iran, and Saudi Arabia.

By the late 1970s, an increasing number of Americans believed that the Soviet hard-liners viewed détente as a mere tactic to lull the West into relaxing its vigilance. Soviet Communist Party Chief Leonid Brezhnev reinforced this view, boasting of gains that his country had made at the United States’ expense—in Vietnam, Angola, Cambodia, Ethiopia, and Laos.

An alarming Soviet arms buildup contributed to the sense that détente was not working. By 1975, the Soviet Union had 50 percent more intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) than the United States, three times as many army personnel, three times as many attack submarines, and four times as many tanks. The United States continued to have a powerful strategic deterrent, holding a 9,000 to 3,200 advantage in deliverable nuclear bombs and warheads. But the arms gap between the countries was narrowing.

Foreign Policy Triumphs

In the Middle East, President Carter achieved his greatest diplomatic success by negotiating peace between Egypt and Israel. Since the founding of Israel in 1948, Egypt’s foreign policy had been built around destroying the Jewish state. In 1977, Anwar el-Sadat, the practical and farsighted leader of Egypt, decided to seek peace with Israel. It was an act of rare political courage, as Sadat risked alienating Egypt from the rest of the Arab world without a firm commitment for a peace treaty with Israel.

Although both countries wanted peace, major obstacles had to be overcome. Sadat wanted Israel to retreat from the West Bank of the Jordan River and from the Golan Heights (which it had taken from Jordan in the 1967 war), to recognize the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), to provide a homeland for the Palestinians, to relinquish its unilateral hold on the city of Jerusalem, and to return the Sinai to Egypt. Such conditions were unacceptable to Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, who refused to consider recognition of the PLO or the return of the West Bank. By the end of 1977, Sadat’s peace mission had run aground.

Jimmy Carter broke the deadlock by inviting both men to Camp David, the presidential retreat in Maryland, for face-to-face talks. For two weeks in September 1978, they hammered out peace accords. Although several important issues were left unresolved, Begin did agree to return the Sinai to Egypt. In return, Egypt promised to recognize Israel, and as a result, became a staunch U.S. ally. For Carter it was a proud moment. Unfortunately, the rest of the Arab Middle East denounced the Camp David accords, and in 1981, Sadat paid for his vision with his life when anti-Israeli Egyptian soldiers assassinated him.

In 1978, Carter also pushed the Panama Canal Treaty through the Senate, which provided for the return of the Canal Zone to Panama and improved the image of the United States in Latin America. One year later, he extended diplomatic recognition to the People’s Republic of China. Carter’s successes in the international arena, however, would soon be overshadowed by the greatest challenge of his presidency—the Iran hostage crisis.

No Islands of Stability

Tragically, American foreign policy has historically supported many countries that hold power through murder, torture, and other violations of human rights—practices that are an affront to basic American values. During the presidency of Jimmy Carter, the United States began to show a growing regard for the human rights practices of its allies. Carter was convinced that American foreign policy should embody the country’s basic moral beliefs. In 1977, Congress began to require reports on human rights conditions in countries receiving American aid.

Iran had been one of the most frequently cited nations accused of practicing torture. Estimates of the number of political prisoners in Iran ranged from 25,000 to 100,000. It was widely believed that most of them had been tortured by SAVAK, the secret police.

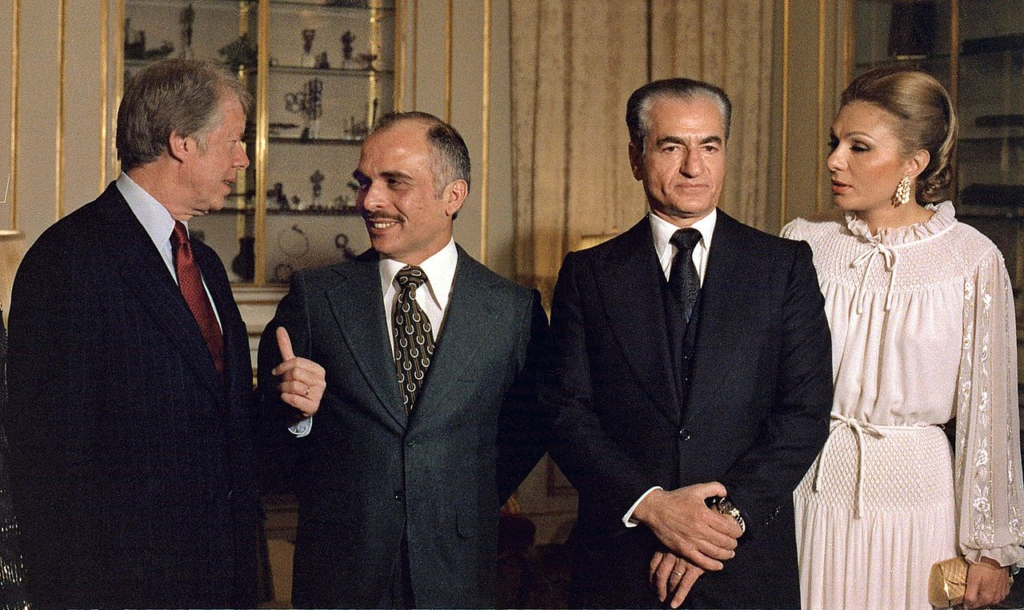

Since the end of World War II, Iran had been a valuable friend of the United States in the troubled Middle East. In 1953, the CIA had worked to place the young shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, in power, helping to overthrow a democratically elected prime minister. During the next 25 years, the shah often repaid the debt. He allowed the United States to establish electronic listening posts in northern Iran along the border of the Soviet Union, and during the 1973-1974 Arab oil embargo, he continued to sell oil to the United States. The shah also bought arms from the United States, helping to ease the American balance of payments problem. Few world leaders were more loyal to the United States.

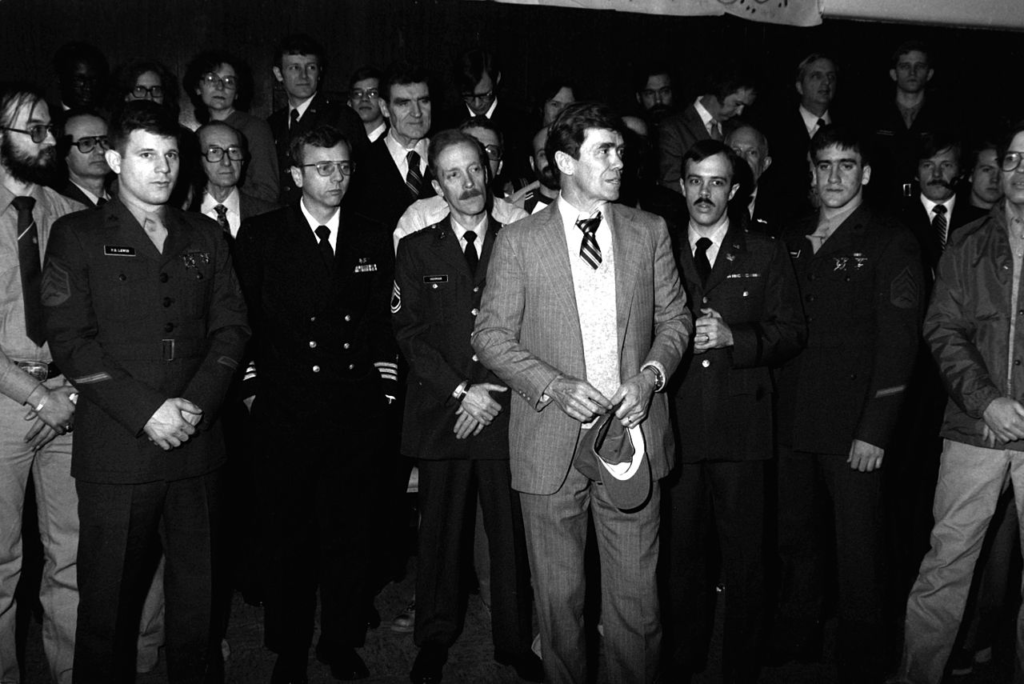

Like his predecessors, President Carter was willing to overlook the shah’s violations of human rights. Carter visited Iran in late December 1977 to demonstrate American support. He applauded Iran as “an island of stability in one of the most troubled areas of the world” and praised Mohammad Reza as a great leader who had won “the respect and the admiration and love” of his people.

The shah was indeed popular among wealthy Iranians, but in the slums of Teheran and in rural, poverty stricken villages, there was little respect, admiration, or love for his regime. Led by a fundamentalist Islamic clergy and emboldened by want, the masses of Iranians turned against the shah and his Westernization policies. In early fall of 1978, the revolutionary surges in Iran gained force. The shah, who had once seemed so powerful and secure, was paralyzed by indecision, alternating between ruthless suppression and attempts to liberalize his regime. In Washington, Carter also vacillated, uncertain whether to stand firmly behind the shah or to cut his losses and prepare to deal with a new government in Iran.

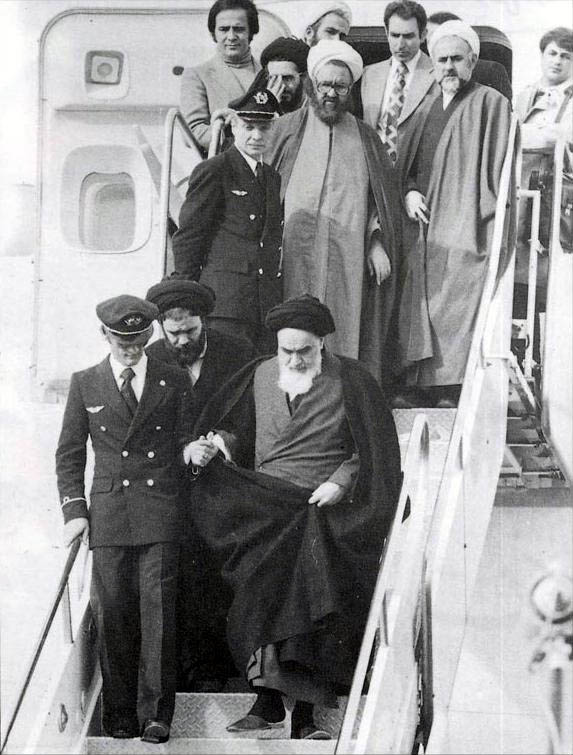

In January 1979, the shah fled to Egypt. Exiled religious leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, returned to Iran from exile in France, preaching the doctrine that the United States was the “Great Satan” behind the shah. Relations between the United States and the new Iranian government were terrible, but Iranian officials warned that they would become infinitely worse if the shah were granted asylum. Nevertheless, Carter permitted the shah to enter the United States for treatment of lymphoma. The reaction in Iran was severe.

On November 4, 1979, Iranian supporters of Khomeini invaded the American embassy in Teheran and captured 66 Americans, 13 of whom were freed several weeks later. The rest were held hostage for 444 days and were the objects of intense political interest and media coverage.

Carter was helpless. Because Iran was not a stable country in any recognizable sense, its government was not susceptible to pressure. Iran’s demands—the return of the shah to Iran and the admission of U.S. guilt in supporting the shah—were unacceptable. Carter devoted far too much attention to the almost insoluble problem. The hostages stayed in the public spotlight, in part, because Carter kept them there.

Carter’s foreign policy problems mounted in December 1979, when the Soviet Union sent tanks into Afghanistan. In response, the Carter administration embargoed grain and high-technology exports to the Soviet Union and boycotted the 1980 Olympics in Moscow (the Soviet Union gradually withdrew its troops a decade later).

As public disapproval of the president’s handling of the Iran crisis increased, some Carter advisers advocated the use of force to free the hostages. At first Carter disagreed, but eventually, he authorized a rescue attempt. It failed, and Carter’s position became even worse. Negotiations finally brought the hostages’ release, but they also brought humiliation to Carter. The hostages were held until minutes after Ronald Reagan, Carter’s successor, had taken the oath of office as president.

When Carter left office in January 1981, many Americans judged his presidency a failure. Instead of being remembered for the good he accomplished for the Middle East at Camp David, he was remembered for what he failed to accomplish. The Iranian hostage crisis had become emblematic of the perception that America’s role in the world had declined.