New Style Presidents in the Age of Inflation

New Style Presidents

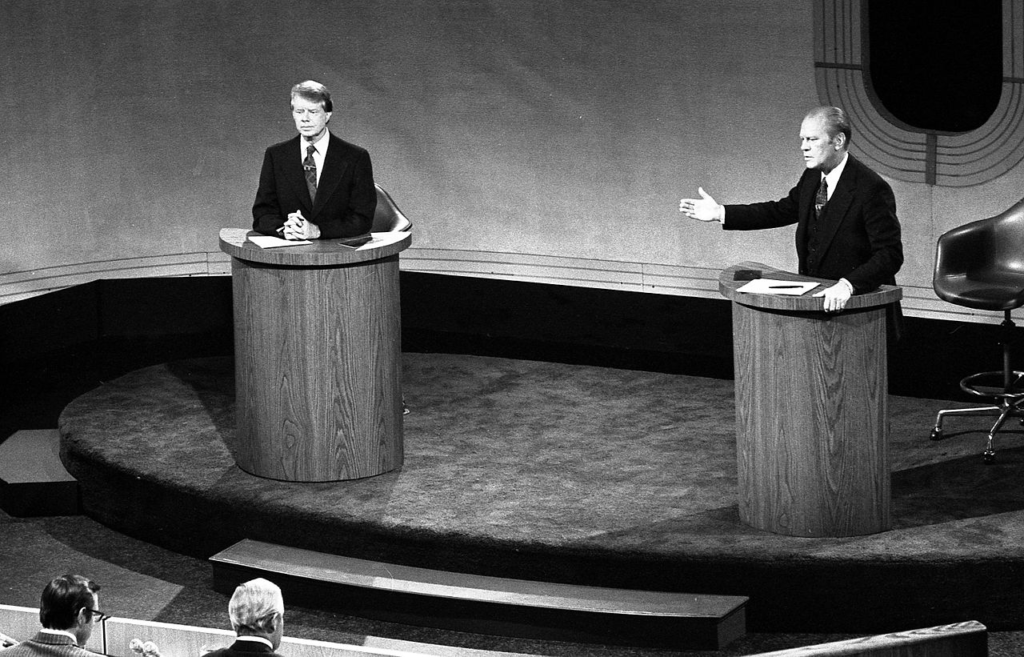

In contrast to Nixon’s abuses of presidential power, the next two presidents, Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter, cultivated reputations as honest, forthright leaders. Both were men of decency and integrity, but neither established reputations as strong, dynamic leaders. Although many Americans admired their honesty and sincerity, neither Ford nor Carter succeeded in winning the confidence of the American people. Moreover, neither administration had a clear sense of direction. Both Ford and Carter seemed to waffle on major issues of public policy. As a result, both came to be regarded as unsure, vacillating presidents.

A thirteen-year-term congressman from Grand Rapids, Michigan, Gerald Ford dismissed the possibility of pardoning Richard Nixon for his Watergate misdeeds, then changed his mind. In the realm of economic policy, he began by urging tax increases; however, he later called for a large tax cut. His energy policy was crippled by the same indecision. At first, he tried to raise prices by imposing import fees on imported oil and ending domestic price controls then, he abandoned that position in the face of severe political pressure.

Carter, too, suffered from the charge that he modified his stances in the face of political pressure. A two-term Democratic governor from Georgia who defeated Ford in the 1976 presidential election, Carter came to office determined to cut military spending, to call for the abolition of nuclear weapons and to withdrawal of American troops from South Korea. By the end of his term, however, Carter spoke of the need for sustaining growth in defense spending, upgrading nuclear forces in Europe, and developing a new strategic bomber.

Both men were described as “passionless presidents” who failed to project a clear vision of where they wanted to lead the country. But in their defense, both faced serious problems, ranging from dealing with rising oil prices to confronting third-world terrorists.

Wrenching Economic Transformations

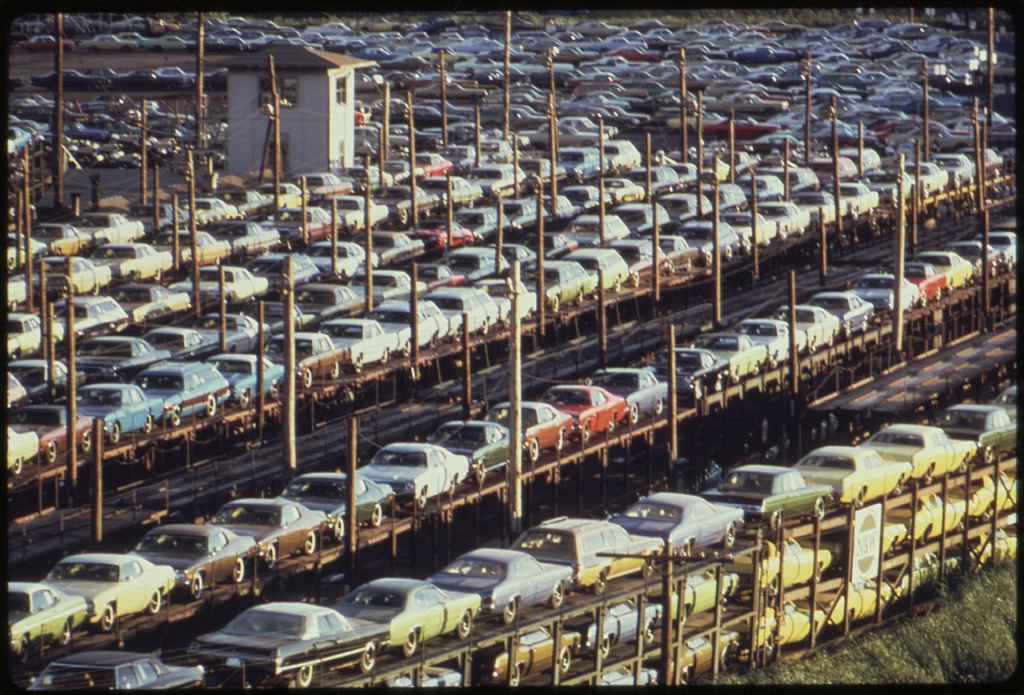

At one time, the car makers in Detroit produced automobiles that mirrored America’s strength and power. They were big, heavy, powerful cars with such expensive options as power windows, power brakes, and power steering. So what if they were not energy-efficient (most got ten to thirteen miles per gallon)? Gas was cheap—just 37 cents a gallon in 1973. The public kept buying big cars, Detroit kept producing them, and the automobile industry reaped big profits.

By the late 1970s, the rising costs of Middle Eastern oil forced the American automotive industry to rethink its strategy. Emerging Arab nationalism and the solidarity of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) drove the price of a gallon of gas toward the dollar mark. American drivers started purchasing smaller, better-engineered, fuel-efficient cars from Japan and Europe. By 1982, Japanese cars had captured thirty percent of the U.S. market.

Since 1973, the American economy has undergone a series of wrenching economic transformations. Economic growth slowed. Productivity flagged. Inflation rose and major industries faltered in the face of foreign competition. Despite a massive influx of women into the work force, family wages stagnated. A quarter century of rapid post-World War II economic growth had come to an end.

The Age of Inflation

In 1967, the average price of a three-bedroom house was $17,000. A brand new Cadillac convertible went for $6,700 and a new Volkswagen $1,497, a Hershey chocolate bar sold for a nickel, and a pound of sirloin for 89 cents. Two decades later, the prices of these products had quadrupled.

The upsurge in inflation started when Lyndon Johnson decided to fight the Vietnam War without raising taxes enough to pay for it. By 1968, the war was costing the United States $3 billion dollars a month, and the federal budget skyrocketed to $179 billion. With hundreds of thousands of Americans in the military service and even more working in defense related industries, unemployment fell, wages rose, and government deficits increased. Inflation was further fueled by a series of crop failures and sharp rises in commodities, especially oil.

High inflation had many negative effects on the American economy. It wiped out many families’ savings. It provoked labor turmoil, as workers went on strike for higher wages. It encouraged speculation in tangible assets—like art, precious metals, and real estate—rather than productive investment in new factories and technology. Above all, certain organized interest groups were able to keep up with inflation, while other less powerful groups, such as welfare recipients, saw the value of their benefits decline significantly.

Inflation reduced the purchasing power of most Americans. For over a decade, real family wages remained flat. By the end of the 1970s, wages had climbed just $36 over 1973 levels. Yet, inflation raised the prices of virtually all goods and services. Health care and housing, in particular, experienced price rises far above the inflation rate. The consequences were a sharp increase in the number of Americans unable to afford health insurance, and a dramatic increase in the cost of housing, which resulted in an increase in homelessness.

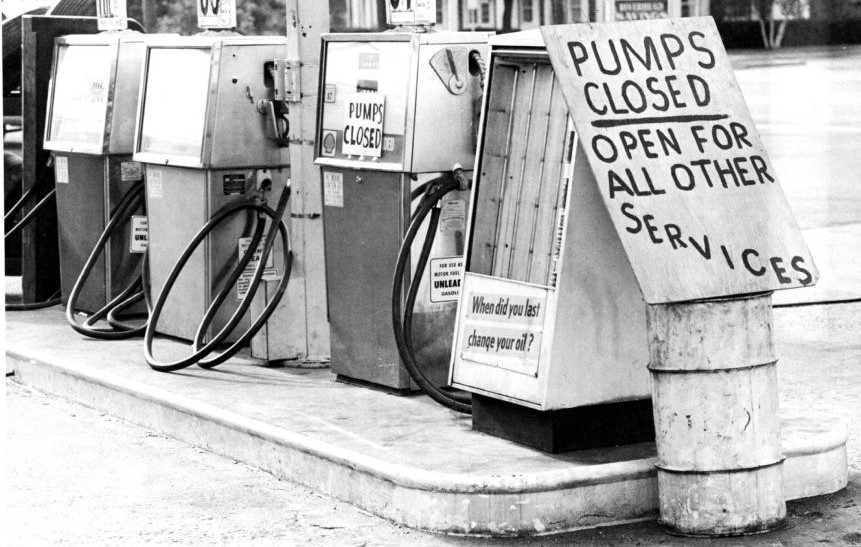

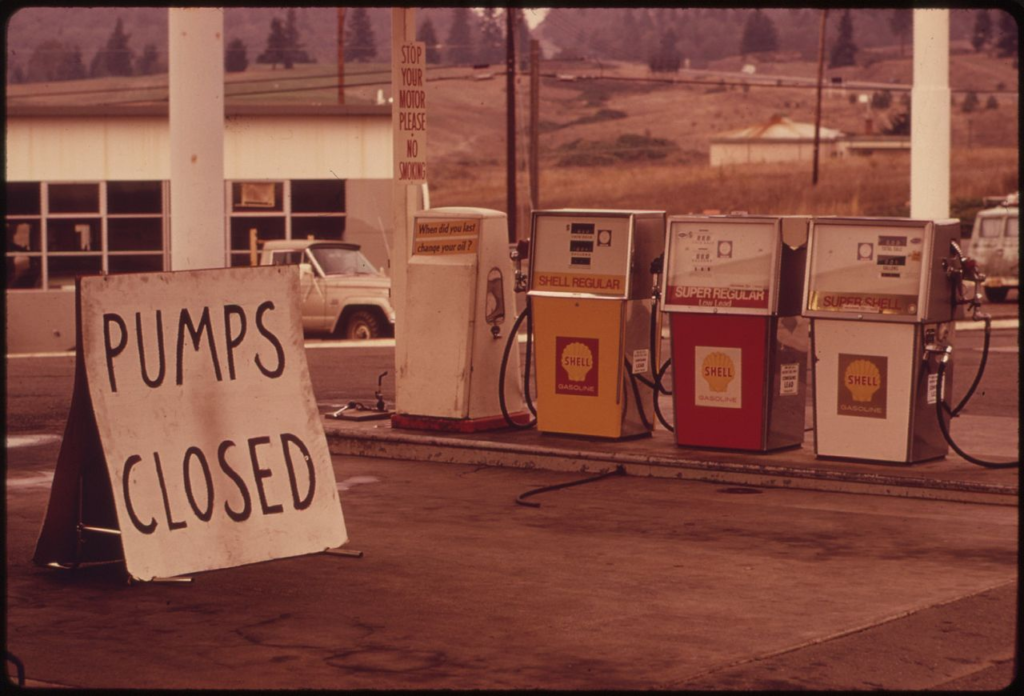

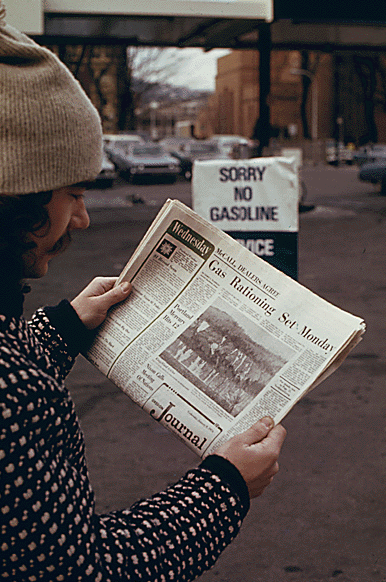

Oil Embargo

Political unrest in the oil-rich Middle East contributed significantly to America’s economic troubles. After suffering a humiliating defeat at the hands of Israel in the 1973 Yom Kippur War, Arab leaders unsheathed a new political weapon—oil. In order to pressure Israel out of territory conquered in the 1967 and 1973 wars, Arab nations cut oil production 25 percent and embargoed all oil exports to the United States. Leading the way was OPEC, founded by Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela in 1960 to fight a reduction in prices by oil companies.

Because Arab nations controlled sixty percent of the oil reserves in the non-Communist world, they had the Western nations over a barrel. Production cutbacks produced an immediate global shortage. The United States imported a third of its oil from Arab nations. Western Europe imported 72 percent from the Middle East; Japan, 82 percent. Gas prices rose, long lines formed at gas pumps, some factories shortened the work week, and some shopping centers restricted business hours.

The oil crisis brought to an end an era of cheap energy. Americans had to learn to live with smaller cars and less heating and air conditioning. But the crisis did have a positive side effect. It increased public consciousness about the environment and stimulated awareness of the importance of conservation. For millions of Americans the lessons were painful to learn.

Foreign Competition

In 1947, the United States was truly the world’s factory. Half of all the world’s manufacturing took place in the United States. Americans made 57 percent of the world’s steel and eighty percent of the world’s cars. It was inevitable that other countries would eventually challenge the dominance that American manufacturers had enjoyed in the aftermath of World War II. During the early 1960s, foreign manufacturers produced six percent of the cars purchased by Americans. That figure climbed to twenty percent in the late 1970s.

The foreign penetration extended far beyond the market for compact cars. Foreign countries began to dominate the highly profitable, technologically-advanced fields,such as consumer electronics, luxury automobiles, and machine tools. Americans discovered that almost exclusively foreign manufacturers now produced technologies their country had pioneered—semiconductors, color televisions, and videocassette recorders. The decline in the American share of the market meant fewer jobs in the American automobile, steel, rubber, and electronics industries. In addition, American and even Japanese companies shifted low-skill production work to such places as South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Indonesia, where goods could be produced more cheaply because of lower wage scales. Few economic developments aroused as much public concern during the 1970s as the loss of American jobs in basic industry. According to one estimate, thirty million jobs disappeared. Displaced workers saw their savings depleted, mortgages foreclosed, and health and pension benefits lost. Even when they found new jobs, they typically had to settle for wages substantially below what they had earned before. Plant shutdowns and closings had profound effects on entire communities, which lost their tax bases at the time when they needed to fund health and welfare services.

Whipping Stagflation

During the 1960s, the primary goal of economic policy was to encourage growth and keep unemployment low. But by the early 1970s, the economy started to suffer from stagnation, high unemployment, and inflation, coupled with stagnant economic growth. This presented economic policymakers with a new and perplexing dilemma since unemployment and inflation usually do not coexist.

The problem with stagflation was the pain of its options. To attack inflation by reducing consumer purchasing power only made unemployment worse. The other choice was no better. Stimulating purchasing power and creating jobs also drove prices higher. Not surprisingly, economic policy during the 1970s was a nightmare of confusion and contradiction.

By 1971, pressures produced by the Vietnam War and federal social spending, coupled with the increase in foreign competition, pushed the inflation rate to fove percent and unemployment to six percent. President Richard Nixon responded by increasing federal budget deficits and devaluing the dollar in an attempt to stimulate the economy and to make American goods more competitive overseas. Nixon also imposed a ninety-day wage and price freeze, followed by a mandatory set of wage-price guidelines, and then, by voluntary controls. Inflation stayed at about four percent during the freeze, but once controls were lifted, inflation resumed its upward climb.

In 1974, during the first oil embargo, inflation hit twelve percent. Gerald Ford, the new president, initially attacked the problem in a traditional Republican fashion, by tightening the money supply by raising interest rates and limiting government spending. In the end, his economic program proved to be no more than a series of ineffectual wage and price guidelines monitored by the federal government. In the subsequent recession, unemployment reached nine percent.

When Jimmy Carter took office in January 1977, unemployment had reached 7.4 percent. Carter responded with an ambitious spending program and called for the Federal Reserve to expand the money supply. Within two years, inflation had climbed to 13.3 percent.

With inflation getting out of hand, the Federal Reserve Board announced in 1979 that it would fight inflation by restraining the growth of the money supply. Unemployment increased, and interest rates rose to their highest levels in the nation’s history. By November 1982, unemployment hit 10.8 percent, the highest since 1940. One out of every five American workers went some time without a job.

Along with high interest rates, the Carter administration adopted another weapon in the battle against stagflation: deregulation. Convinced that regulators too often protected the industries they were supposed to oversee, the Carter administration deregulated air and surface transportation and the savings and loan industry. The effects of deregulation are still hotly contested. Rural towns suffered cutbacks in bus, rail, and air service. Truckers and rail workers lost the economic benefits of regulation. Travelers complained about congested airports. Cable TV viewers resented rising rates. Champions of deregulation, however, argued that the policy increased competition, stimulated new investment, and forced inefficient firms either to become more efficient or to close down.