Nixon and Watergate

Watergate

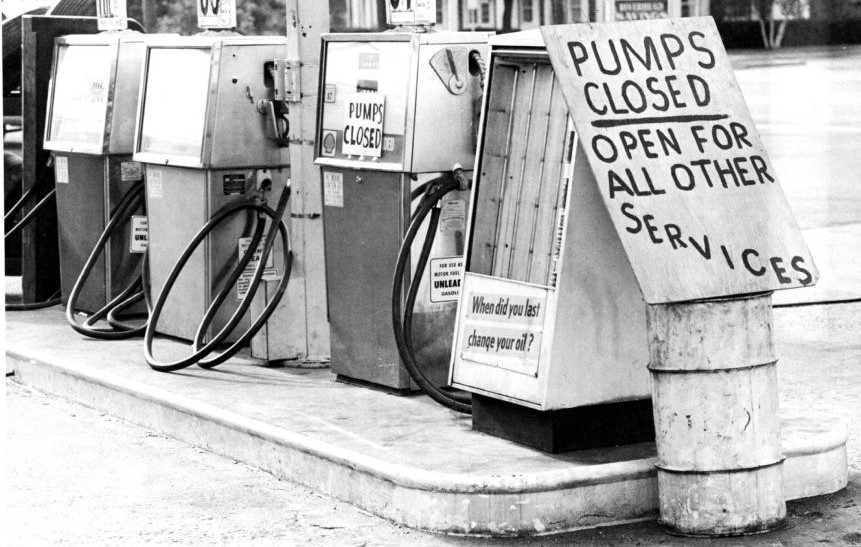

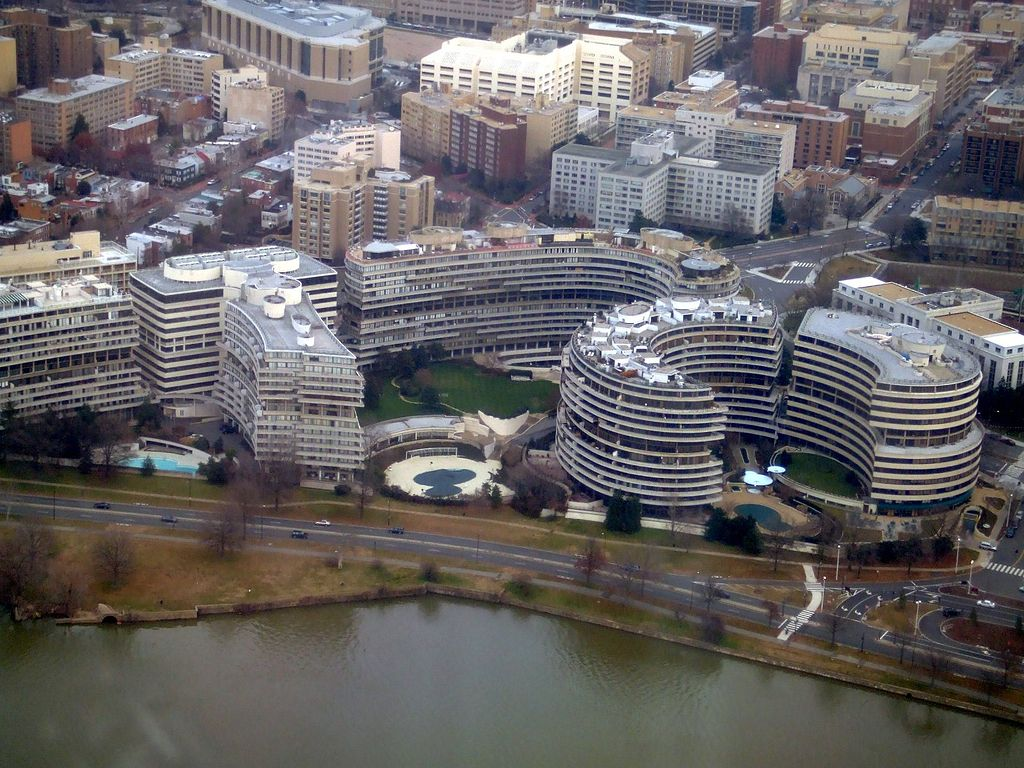

Shortly after 1 a.m. on June 17, 1972, a security guard at the Washington, D.C., Watergate office complex spotted a strip of masking tape covering the lock of a basement door. He removed it. A short while later, he found the door taped open again. He called the police, who found two more taped locks and a jammed door leading into the offices of the Democratic National Committee. Inside they discovered five men carrying cameras and electronic eavesdropping equipment.

At first, the Watergate break-in seemed like a minor incident. The identities of the burglars, however, suggested something more serious. One, James McCord, was Chief Security Coordinator of the Committee for the Re-election of the President (CREEP). Others had links to the CIA.

Over the course of the next year, it became clear that the break-in was one in a series of secret operations coordinated by Richard M. Nixon’s White House. Financed by illegal campaign contributions, these operations posed a threat to America’s constitutional system of government and, eventually, forced Richard Nixon to resign the presidency.

The Watergate break-in had its roots in Richard Nixon’s obsession with secrecy and political intelligence. To stop “leaks” of information to the press, in 1971 the Nixon White House assembled a team of “plumbers,” consisting of former CIA operatives. This private police force, paid for in part by illegal campaign contributions, engaged in a wide range of criminal acts, including phone tapping and burglary, against those on its “enemies list.”

In 1972, when President Nixon was running for re-election, CREEP authorized another series of illegal activities. It hired Donald Segretti to stage “dirty tricks” against potential Democratic nominees, which included mailing letters that falsely accused one candidate of homosexuality and fathering an illegitimate child. It considered a plan to use call girls to blackmail Democrats at their national convention and to kidnap anti-Nixon radical leaders. The committee also authorized $250,000 for intelligence-gathering operations. Four times the committee sent burglars to break into Democratic headquarters.

Precisely what the campaign committee hoped to learn from these intelligence-gathering activities remains a mystery. It seems likely that it was seeking information about the Democratic Party’s campaign strategies and any information the Democrats had about illegal campaign contributions to the Republican Party.

On June 23, 1972—six days after the botched break-in—President Nixon ordered aides to block an FBI investigation of the White House involvement in the break-in on grounds that an investigation would endanger national security. He also counseled his aides to lie under oath, if necessary.

The Watergate break-in did not hurt Nixon’s re-election campaign. Between the activities of the burglars and the president were layers of deception that had to be carefully peeled away. Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, sensing that the break-in was only part of a larger scandal, slowly pieced together part of the story. Facing long jail terms, some of the burglars began to tell the truth. The truth illuminated a path leading to the White House.

If Nixon had few political friends, he had legions of enemies. Over the years he had offended or attacked many Democrats—and a number of prominent Republicans. His detractors latched onto the Watergate issue with the tenacity of bulldogs.

The Senate appointed a special committee to investigate the Watergate scandal. Most of Nixon’s top aides continued the cover-up. John Dean, the President’s Counsel, did not. Throughout the episode he had kept careful notes, and in a quiet, precise voice he told the Senate Watergate Committee that the president was deeply involved in the cover-up. The matter was still not solved. All the committee had was Dean’s word against the other White House aides.

On July 16, 1973, a former White House employee dropped a bombshell by testifying that Nixon had recorded all Oval Office conversations. Whatever Nixon and his aides had said about Watergate in the Oval Office, therefore, was faithfully recorded on tape.

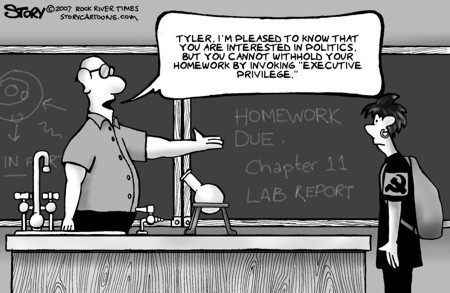

Nixon tried to keep the tapes from the committee by invoking executive privilege. He insisted that a president had a right to keep confidential any White House communication, whether or not it involved sensitive diplomatic or national security matters. Archibald Cox, a special prosecutor investigating the Watergate affair, persisted in demanding the tapes. In response, Nixon ordered his attorney general, Elliot Richardson, to fire Cox. Richardson refused and resigned. Richardson’s assistant, William Ruckelshaus, also resigned. Ruckelshaus’s assistant, Robert Bork, finally fired Cox, but Congress forced Nixon to name a new special prosecutor, Leon Jaworski.

In the midst of the Watergate investigations another scandal broke. Federal prosecutors accused Vice President Spiro Agnew of extorting payoffs from building contractors while he was Maryland’s governor and a Baltimore County executive. In a plea bargain, Agnew pleaded no contest to a relatively minor charge—that he had falsified his income tax in 1967—in exchange for a $10,000 fine. Gerald Ford, whom Nixon appointed, succeeded Agnew as Vice President.

The Watergate scandal gradually came to encompass not only the cover-up but a wide range of presidential wrongdoings. These transgressions included extending political favors to powerful business groups in exchange for campaign contributions, misusing public funds, deceiving Congress and the public about the secret bombing of Cambodia; authorizing illegal domestic political surveillance and espionage against dissidents, political opponents, and journalists, and attempting to use FBI investigations and income tax audits by the IRS to harass political enemies.

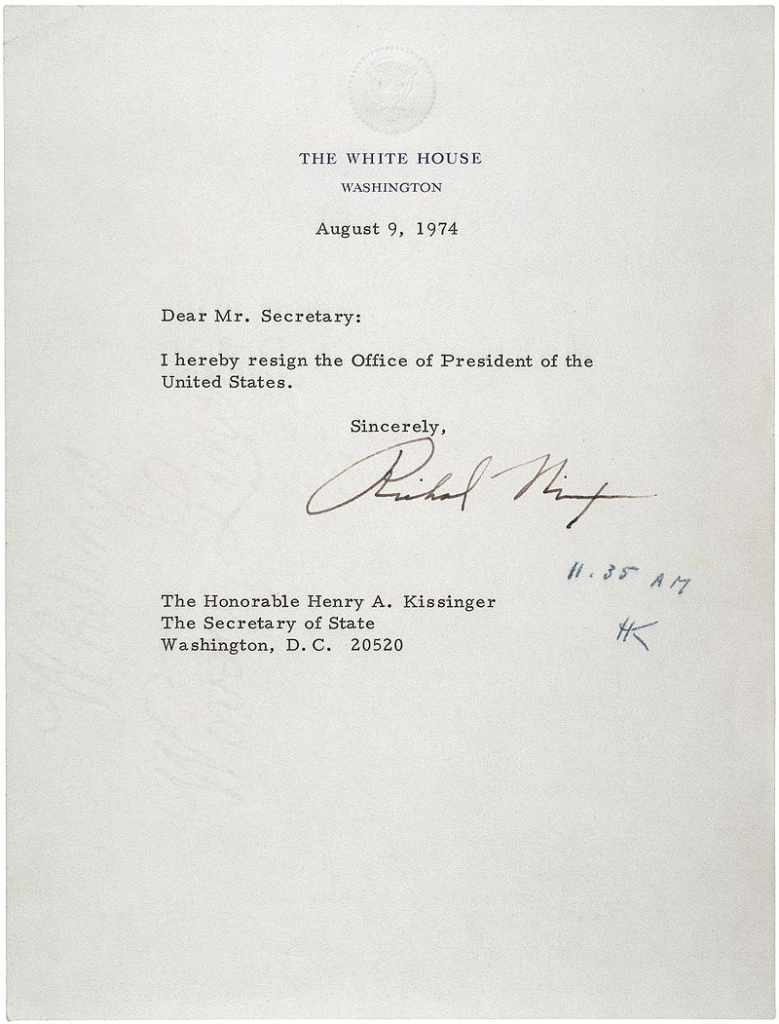

On July 24, 1974, the House Judiciary Committee recommended that the House of Representatives impeach Nixon for obstruction of justice, abuse of power, and refusal to relinquish the tapes. On August 5, Nixon obeyed a Supreme Court order to release the tapes, which confirmed Dean’s detailed testimony. Nixon had indeed been involved in a cover-up. On August 9, he became the first American president to resign from office. The following day Gerald Ford became the new president. “Our long national nightmare,” he said, “is over.”

Impeachment

Prior to the enactment of the U.S. Constitution, there was no legal mechanism to remove a head of state. A king or queen might be overthrown and a prime minister might lose a vote of confidence. But there was no mechanism for lawfully removing a head of government for a crime, corruption, malfeasance, or mere incompetence.

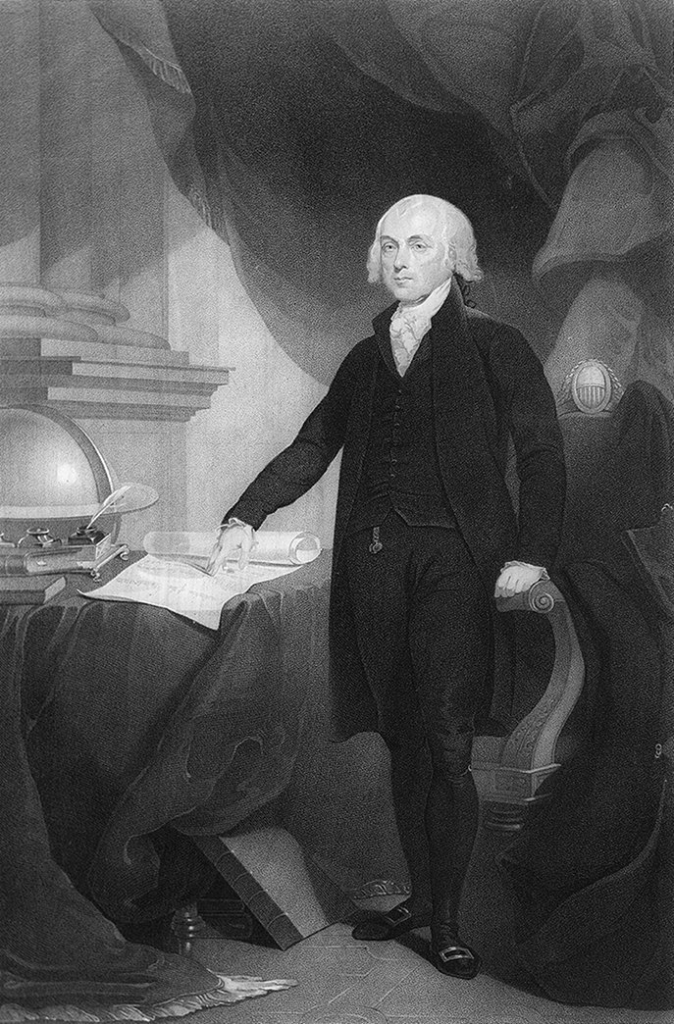

At the Constitutional Convention of 1787, it was proposed that a president could be removed “on impeachment and conviction for malpractice or neglect of duty.” One delegate thought that there was no need for an impeachment process, since a president guilty of a crime would not be reelected. Others worried that the possibility of impeachment might threaten the independence of the Executive Branch, since Congress could always use the possibility of removal from office to influence presidential actions.

James Madison responded by enumerating possible reasons for impeachment: The President “might lose his capacity after his appointment. He might pervert his administration into a scheme of peculation or oppression. He might betray his trust to foreign powers.”

When the convention finally voted on the question “Shall the executive be removable on impeachments?” every state delegation voted in favor except for Massachusetts and South Carolina.

Then, the delegates had to decide on the grounds for impeachment. One committee recommended “treason, bribery, and corruption.” Another committee held that only treason and bribery were appropriate grounds. A Virginia delegate, George Mason, proposed adding “maladministration,” but Madison thought that this was too vague, and would allow Congress to impeach and remove a President on almost any grounds.

In the end, the Constitution set a very high bar for impeachment and removal from office. A president may only be impeached and convicted for “Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.” In addition, a majority of the House of Representatives had to vote to impeach and two-thirds of the Senate had to vote to convict and remove.

While the Constitution’s intent is not wholly clear, it does seem apparent that the reference to misdemeanors does not refer to an offense like burglary or loitering. Nor does the Constitutional provision apply to maladministration. Rather, as Madison put it, the provision was intended to defend “the community against the incapacity, negligence, or perfidy of the Chief Magistrate.”

Impeachment, in short, requires proof of significant abuse of power or breach of the public trust. It was not to be used hastily or for partisan purposes. The framers of the Constitution were particularly concerned about damaging the separation of powers.

As a result, attempts to impeach and remove a president have been rare. Three times, the House of Representatives tried and failed to impeach President John Tyler, for abusing his veto power. President Andrew Johnson was impeached and ultimately acquitted by a single vote for violating the Tenure of Office Act that is, disobeying a statute, which the Supreme Court later declared unconstitutional, by removing the Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, from office. Of course, the real reason was Johnson’s opposition to Congressional Reconstruction.

In the twentieth century, there were two serious attempts at presidential impeachment. Richard M. Nixon was accused of obstruction of justice, abuse of power, and contempt of Congress in the Watergate affair. Bill Clinton was charged with perjury, lying under oath about his relationship with a White House intern, Monica Lewinsky, and obstruction of justice, by attempting to conceal evidence about the affair.

In the Nixon case, a House committee approved the three articles of impeachment, but these never reached the floor of the full House, since the President resigned. In the Clinton case, 45 Democrats and five Republicans voted “not guilty” on all charges.

Officers other than the president can be impeached. In all, fifteen federal judges have been impeached, although only eight have been removed from the bench.

Crisis of Political Leadership

The Vietnam War and the Watergate scandal had a profound effect on the presidency. The office suffered a dramatic decline in public respect, and Congress became increasingly unwilling to defer to presidential leadership. Congress enacted a series of reforms that would make future abuses of presidential authority less likely. In the process, Congress recaptured constitutional powers that had been ceded to an increasingly dominant executive branch.

Restraining the Imperial Presidency

Over the course of the twentieth century, the presidency gradually supplanted Congress as the center of federal power. Presidential authority increased, presidential staffs grew in size, and the executive branch gradually acquired a dominant relationship over Congress.

Beginning with Theodore Roosevelt, the president, and not Congress, established the nation’s legislative agenda. Increasingly, Congress ceded its budget-making authority to the president. Presidents even found a way to make agreements with foreign nations without congressional approval. After World War II, presidents substituted executive agreements for treaties requiring approval of the Senate. Even more important, presidents gained the power to take military action, despite the fact that Congress is the sole branch of government empowered by the Constitution to declare war.

No president went further than Richard Nixon in concentrating powers in the presidency. He refused to spend funds that Congress had appropriated. He claimed executive privilege against disclosure of information on administration decisions. He refused to allow key decision makers to be questioned before congressional committees; he reorganized the executive branch and broadened the authority of new cabinet positions without congressional approval. During the Vietnam War, he ordered harbors mined and bombing raids launched without consulting Congress.

Watergate brought a halt to the “imperial presidency” and the growth of presidential power. Over the president’s veto, Congress enacted the War Powers Act (1973), which required future presidents to obtain authorization from Congress to engage U.S. forces in foreign combat for more than ninety days. Under the law, a president who orders troops into action abroad must report the reason for this action to Congress within 48 hours.

In the wake of the Watergate scandal, Congress passed a series of laws designed to reform the political process. Disclosures during the Watergate investigations of money-laundering led Congress to provide public financing of presidential elections, public disclosure of sources of funding, limits on private campaign contributions and spending, and enforcement of campaign finance laws by an independent Federal Election Commission. To make it easier for the Justice Department to investigate crimes in the executive branch, Congress required the attorney general to appoint a special prosecutor to investigate accusations of illegal activities. To re-assert its budget-making authority, Congress created a Congressional Budget Office and specifically forbade a president to impound funds without its approval. To open government to public scrutiny, Congress opened more committee deliberations and enacted the Freedom of Information Act, which allows the public and press to request the declassification of government documents.

Some of the post-Watergate reforms have not been as effective as reformers anticipated. The War Powers Act has never been invoked. Campaign financing reform has not curbed the ability of special interests to curry favor with politicians or the capacity of the very rich to outspend opponents.

On the other hand, Congress has had somewhat more success in reining in the FBI and the CIA. During the 1970s, congressional investigators discovered that these organizations had, in defiance of federal law, broken into the homes, tapped the phones, and opened the mail of American citizens, illegally infiltrated anti-war groups and black radical organizations, and accumulated dossiers on dissidents, which had been used by presidents for political purposes. Investigators also found that the CIA had been involved in assassination plots against foreign leaders—among them Fidel Castro—and had tested the effects of radiation, electric shock, and drugs, such as LSD on unsuspecting citizens. In the wake of these investigations, the government severely limited CIA operations in the United States and laid down strict guidelines for FBI activities. To tighten congressional control over the CIA, Congress established a joint committee to supervise its operations.

Executive Privilege

Since the Eisenhower administration, presidents have claimed the power to withhold information from the other branches of government in order to protect military, diplomatic, or national security secrets that could place the country at risk. Presidents have also claimed the right to prevent Congress or the courts from access to internal policy deliberations between the president or top White House aides and subordinate members of the executive branch on the grounds that this would inhibit the candor of such communications.

Executive privilege is not mentioned in the Constitution, and its scope and limits are unclear. Only rarely have the courts ruled on a president’s right to withhold information. In a 1974 case involving the Watergate Affair the Supreme Court ruled for the first time that presidents did have a right to executive privilege for “confidential executive deliberations” about matters of policy having nothing to do with national security. This privilege derives from the separation of powers, but is not absolute. The Court ordered the White House had to give tapes of Oval Office conversations to prosecutors because an assertion of privilege “must yield to the demonstrated, specific need for evidence in a pending criminal trial.” In 1997, the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit ruled that a president had to hand over materials pertinent to a grand jury investigation.

Most matters involving the disclosure of military, diplomatic, and national security secrets with Congress have been resolved through negotiations, rather than litigation. It is widely believed that were the courts to intervene, judges would have to balance the president’s interest in privacy against Congress’s need for information to perform its legislative and oversight responsibilities.