The Mexican War

The Mexican War

Fifteen years before the United States was plunged into Civil War, it fought a war against Mexico that added half a million square miles of territory to the United States. Not only was it the first American war fought almost entirely outside the United States, it was also the first American war to be reported, while it happened, by daily newspapers.

It was a controversial war that bitterly divided American public opinion. And it was the war that gave young officers named Ulysses S. Grant, Robert E. Lee, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, William Tecumseh Sherman, and George McClellan their first experience in a major conflict.

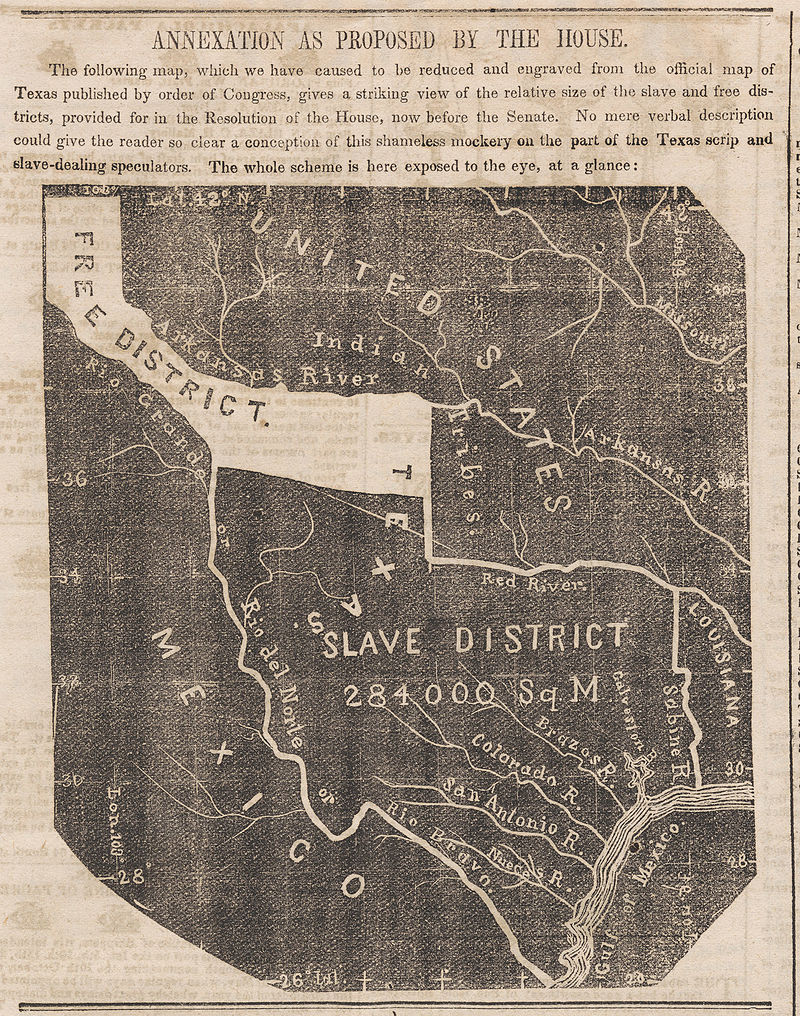

The underlying cause of the Mexican War was the movement of American pioneers into lands claimed by Mexico. The immediate reason for the conflict was the annexation of Texas in 1845. After the defeat at San Jacinto in 1836, Mexico made two abortive attempts in 1842 to reconquer Texas. Even after these defeats, Mexico refused to recognize Texan independence and warned the United States that the annexation of Texas would be tantamount to a declaration of war.

In early 1845, when Congress voted to annex Texas, Mexico expelled the American ambassador and cut diplomatic relations. But, it did not declare war.

President Polk told his commanders to prepare for the possibility of war. He ordered American naval vessels to position themselves outside Mexican ports. And he dispatched American forces in the Southwest to Corpus Christi, Texas.

Peaceful settlement of the two countries’ differences still seemed possible. In the fall of 1845, the President offered $5 million if Mexico agreed to recognize the Rio Grande River as the southwestern boundary of Texas. Earlier, the Spanish government had defined the Texas boundary as the Nueces River, 130 miles north and east of the Rio Grande. No Americans lived between the Nueces and the Rio Grande, although many Hispanics lived in the region.

The United States also offered up to $5 million for the province of New Mexico—which included Nevada and Utah and parts of four other states—and up to $25 million for California. Polk was anxious to acquire California because in mid-October 1845, he had been led to believe that Mexico had agreed to cede California to Britain as payment for debts. Polk also dispatched a young Marine Corps lieutenant, Archibald H. Gillespie, to California, apparently to foment revolt against Mexican authority.

The Mexican government, already incensed over the annexation of Texas, refused to accept an American envoy. The failure of the negotiations led Polk to order Brigadier General Zachary Taylor to march 3,000 troops southwest from Corpus Christi, Texas, to “defend the Rio Grande” River. Late in March of 1846, Taylor and his men set up camp along the Rio Grande, directly across from the Mexican city of Matamoros, on a stretch of land claimed by both Mexico and the United States.

On April 25, 1846, a Mexican cavalry force crossed the Rio Grande and clashed with a small American squadron, forcing the Americans to surrender after the loss of several lives. On May 11, after he received word of the border clash, Polk asked Congress to acknowledge that a state of war already existed “by the act of Mexico herself…notwithstanding all our efforts to avoid it.” “Mexico,” the President announced, “has passed the boundary of the United States, has invaded our territory and shed American blood upon the American soil.” Congress responded with a declaration of war.

The Mexican War was extremely controversial. Its supporters blamed Mexico for the hostilities because it had severed relations with the United States, threatened war, and refused to receive an American emissary or to pay the damage claims of American citizens. In addition, Mexico had “invaded our territory and shed American blood on American soil.” Opponents denounced the war as an immoral land grab by an expansionistic power against a weak neighbor that had been independent barely two decades.

The war’s critics claimed that Polk deliberately provoked Mexico into war by ordering American troops into disputed territory. A Delaware Senator declared that ordering Taylor to the Rio Grande was “as much an act of aggression on our part as is a man’s pointing a pistol at another’s breast.” Critics also argued that the war was an expansionist power play dictated by an aggressive Southern slave owners intent on acquiring more slave states.

The Face of Battle

American forces quickly conquered Mexico’s northernmost provinces. In less than two months, Colonel Stephen Kearny marched his 1,700-man army more than a thousand miles, occupied Santa Fe, and declared New Mexico’s 80,000 inhabitants American citizens.

Meanwhile, American settlers in California’s Sacramento Valley, fearful that Mexican authorities were about to expel them from the region, revolted. In early July, U.S. naval forces under Commodore John Sloat captured the California town of Monterey and proclaimed California a part of the United States.

Despite the unbroken string of American victories, Mexico refused to negotiate. In disgust, Polk ordered General Winfield Scott to invade central Mexico from the sea, march inland, and capture Mexico City. On March 9, 1847, the Mexicans allowed Scott and a force of 10,000 men to land unopposed at Veracruz on Gulf of Mexico. Scott’s troops then began to march on the Mexican capital. On September 14, 1847, the Americans entered the Mexican capital, and raised the American flag over Mexico City—an event memorialized in the Marine Corps hymn with the line “from the halls of Montezuma.”

Despite the capture of their capital, the Mexicans refused to surrender. Hostile crowds staged demonstrations in the streets, and snipers fired shots and hurled stones and broken bottles from the tops of flat-roofed Mexican houses. Outside the capital, belligerent civilians attacked army supply wagons, and guerrilla fighters harassed American troops. Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts expressed the prevailing sentiment: “Mexico is an ugly enemy. She will not fight—and will not retreat.”

War Fever and Antiwar Protests

During the first few weeks following the declaration of war a frenzy of pro-war hysteria swept the country. Two hundred thousand men responded to a call for 50,000 volunteers. In New York, placards bore the slogan “Mexico or Death.” Many newspapers, especially in the North, declared that the war would benefit the Mexican people by bringing them the blessings of democracy and liberty. The Boston Times said that an American victory “must necessarily be a great blessing,” because it would bring “peace into a land where the sword has always been the sole arbiter between factions” and would introduce “the reign of law where license has existed for a generation.”

But from the war’s very beginning, a small but highly visible group of intellectuals, clergymen, pacifists, abolitionists, and Whig and Democratic politicians denounced the war as brutal aggression against a “poor, feeble, distracted country.”

Literary and reform circles were particularly vocal in their opposition to the war. Congregationalist minister Theodore Parker declared that if the “war be right then Christianity is wrong, a falsehood, a lie.” William Lloyd Garrison’s militant abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, expressed open support for the Mexican people: “Every lover of Freedom and humanity throughout the world must wish them the most triumphant success.”

Most Whigs supported the war—in part, because two of the leading American generals, Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott, were Whigs, and in part because they remembered that opposition to the War of 1812 had destroyed the Federalist party. But many prominent Whigs, from the South as well as the North, openly expressed opposition. Thomas Corwin of Ohio denounced the war as merely the latest example of American injustice to Mexico: “If I were a Mexican I would tell you, Have you not room enough in your own country to bury your dead.” Henry Clay declared, “This is no war of defense, but one of unnecessary and offensive aggression.”

A freshman Congressman from Illinois named Abraham Lincoln lashed out against the war, calling it immoral, proslavery, and a threat to the nation’s republican values. In Congress, he proposed the so-called “Spot Resolution,” demanding that President Polk identify the precise spot on which Mexicans had “shed American blood on the American soil.” One of Lincoln’s constituents branded him “the Benedict Arnold of our district,” and he was denied renomination by his own party.

As newspapers informed their readers about the hardships of life on the front, public enthusiasm for the war began to fade. The war did not turn out to be the romantic exploit that Americans envisioned. Troops complained that their food was “green with slime” and “acted as an instantaneous emetic.” Diarrhea, amoebic dysentery, measles, and yellow fever ravaged American soldiers. Seven times as many Americans died of disease and exposure as died of battlefield injuries. Of the 90,000 Americans who served in the war, only 1,721 died in action. Another 11,155 died from disease and exposure to the elements.

Public support for the war was further eroded by reports of brutality against Mexican civilians. Newspaper reporters claimed that the chapparral was “strewn with the skeletons of Mexicans sacrificed” by American troops. After one of their members was murdered, the Arkansas volunteer cavalry surrounded a group of Mexican peasants and began an “indiscriminate and bloody massacre of the poor creatures.” A young lieutenant named George G. Meade reported that volunteers in Matamoros robbed the citizens, stole their cattle, and killed innocent civilians “for no other object than their own amusement.” If only a tenth of the horror stories were true, General Winfield Scott wrote, it was enough “to make Heaven weep, & every American of Christian morals blush for his country.”

Dissent even made its way to the battlefield. A group of enlisted Irish-Catholic Americans, shocked by the desecration of Catholic churches, deserted to the Mexican side, formed the San Patricio Battalion, and fought against the American Army. At Churubusco, 65 members of the battalion, which also consisted of foreign nationals resident in Mexico, were captured. Fifty were executed and eleven others were punished with fifty lashes apiece and the letter “D” for deserter branded on their cheeks.

A young essayist and poet named Henry David Thoreau staged the best known act of protest against the Mexican war. On July 23, 1846, the constable of Concord, Massachusetts, arrested the Transcendentalist poet for failure to pay the state poll tax, a head tax on male citizens between the ages of 21 and 70. The constable actually offered to pay the tax if Thoreau was short of money, but Thoreau insisted that he refused to pay on principle, as a protest against his country’s involvement in the Mexican War. The constable then placed Thoreau in the local jail. Thoreau spent only a single night in jail because his tax was paid, much to his disgust, by one of his relatives.

In response to his arrest Thoreau wrote an essay that became a source of inspiration for Leo Tolstoi, Mahatma Gandhi, and Martin Luther King, Jr. Thoreau entitled his essay “Civil Disobedience.” In it, he declared that if all citizens who opposed the Mexican War followed his example and went to jail for their beliefs, the government could be forced to end the conflict. It was the duty of every individual to protest a government policy, even though it had been adopted with majority consent, when it conflicted with moral law. “Any man more right than his neighbor,” he wrote, “constitutes a majority of one.”

So how should an individual protest a moral wrong? Here Thoreau was at his most creative. He described a type of disobedience that disrupted the everyday workings of society and dramatized the moral issues at stake, without resorting to violence. Individual acts of protest, he argued, would awaken the conscience of those people whose consciences could still be stirred.

Out of Thoreau’s jailing grew a legend. Ralph Waldo Emerson, America’s greatest philosopher, visited Thoreau in jail. Emerson asked, “Henry, why are you here?” Thoreau replied, “Why are you not here?”