The Texas Revolution

The Texas Revolution

American settlement in Texas began with the encouragement of first the Spanish, and then the Mexican, governments. In the summer of 1820, Moses Austin, a bankrupt 59-year-old Missourian, asked Spanish authorities for a large Texas land tract, which he would promote and sell to American pioneers.

The request by Austin seemed preposterous. His background was that of a Philadelphia dry goods merchant, a Virginia mine operator, a Louisiana judge, and a Missouri banker. But early in 1821, the Spanish government gave him permission to settle 300 families in Texas. Spain welcomed the Americans for two reasons—to provide a buffer against illegal U.S. settlers, who were creating problems in east Texas even before the grant was made to Austin, and to help develop the land, since only 3,500 native Mexicans had settled in Texas (which was part of the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas).

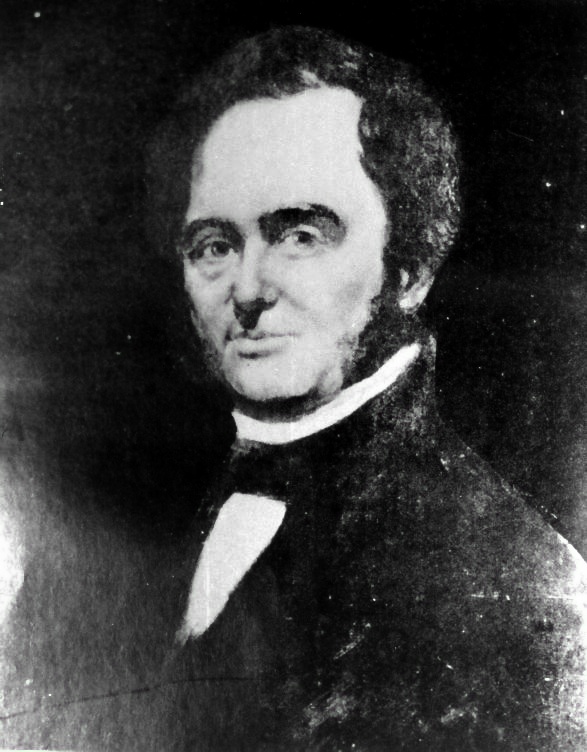

Moses Austin did not live to see his dream realized. On a return trip from Mexico City, he died of exhaustion and exposure. Before he died, his son Stephen promised to carry out the dream of colonizing Texas. By the end of 1824, young Austin had attracted 272 colonists to Texas, and had persuaded the newly independent Mexican government that the best way to attract Americans was to give land agents called empresarios 67,000 acres of land for every 200 families they brought to Texas.

Mexico imposed two conditions on land ownership: settlers had to become Mexican citizens, and they had to convert to Roman Catholicism. By 1830, there were 16,000 Americans in Texas. At that time, Americans formed a 4-to-1 majority in the northern section of Coahuila y Tejas, but people of Hispanic heritage formed a majority in the state as a whole.

As the Anglo population swelled, Mexican authorities grew increasingly suspicious of the growing American presence. Mexico feared that the United States planned to use the Texas colonists to acquire the province by revolution. Differences in language and culture had produced bitter enmity between the colonists and native Mexicans. The colonists refused to learn the Spanish language, maintained their own separate schools, and conducted most of their trade with the United States.

To reassert its authority over Texas, the Mexican government reaffirmed its Constitutional prohibition against slavery, established a chain of military posts occupied by convict soldiers, restricted trade with the United States, and decreed an end to further American immigration.

Santa Anna

These actions might have provoked Texans to revolution. But in 1832, General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, a Mexican politician and soldier, became the president of Mexico. Colonists hoped that he would make Texas a self-governing state within the Mexican republic. But once in power, Santa Anna proved to be less liberal than many Texans had believed. In 1834, he overthrew the constitutional government of Mexico, abolished state governments, and made himself dictator. When Stephen Austin went to Mexico City to try to settle the grievances of the Texans, Santa Anna imprisoned him in a Mexican jail for a year.

On November 3, 1835, American colonists adopted a constitution and organized a temporary government, but voted overwhelmingly against declaring independence. A majority of colonists hoped to attract the support of Mexican liberals in a joint effort to depose Santa Anna and to restore power to the state governments, hopefully including a separate state of Texas.

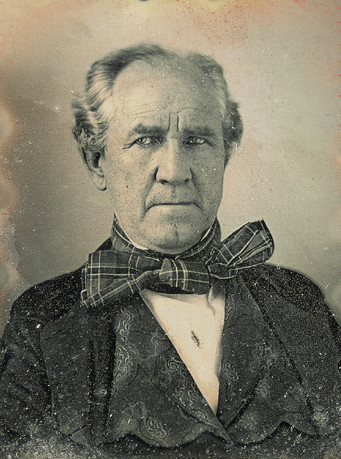

Sam Houston

While holding out the possibility of compromise, the Texans prepared for war by electing Sam Houston commander of whatever military forces he could muster. Houston, one of the larger-than-life figures who helped win Texas independence, had run away from home at the age of fifteen and lived for three years with the Cherokee Indians in eastern Tennessee. During the War of 1812, he had fought in the Creek War under Andrew Jackson. At thirty, he was elected to the House of Representatives, and at thirty-four, he was elected governor of Tennessee. Many Americans regarded him as the heir apparent to Andrew Jackson.

Then, suddenly, in 1829, scandal struck. Houston married a woman seventeen years younger than himself. Within three months, the marriage was mysteriously annulled. Depressed and humiliated, Houston resigned as governor. After wandering about the country as a near derelict, he returned to live with the Cherokee in present day Arkansas and Oklahoma.

During his stay with the tribe, Houston was instrumental in forging peace treaties among several warring Indian nations. In 1832, Houston traveled to Washington to demand that President Jackson live up to the terms of the removal treaty. Jackson did not meet his demands, but instead sent Houston unofficially to Texas to keep an eye on the American settlers and the growing anti-Mexican sentiment.

In the middle of 1835, scattered local outbursts erupted against Mexican rule. Then, a band of some 300 to 500 Texas riflemen, who comprised the entire Texas army, captured the Mexican military headquarters in San Antonio. Revolution was underway.