Opening the West

Opening the West

It took Americans a century and a half to expand as far west as the Appalachian Mountains, a few hundred miles from the Atlantic coast. It took another 50 years to push the frontier to the Mississippi River. By 1830, fewer than 100,000 pioneers crossed the Mississippi.

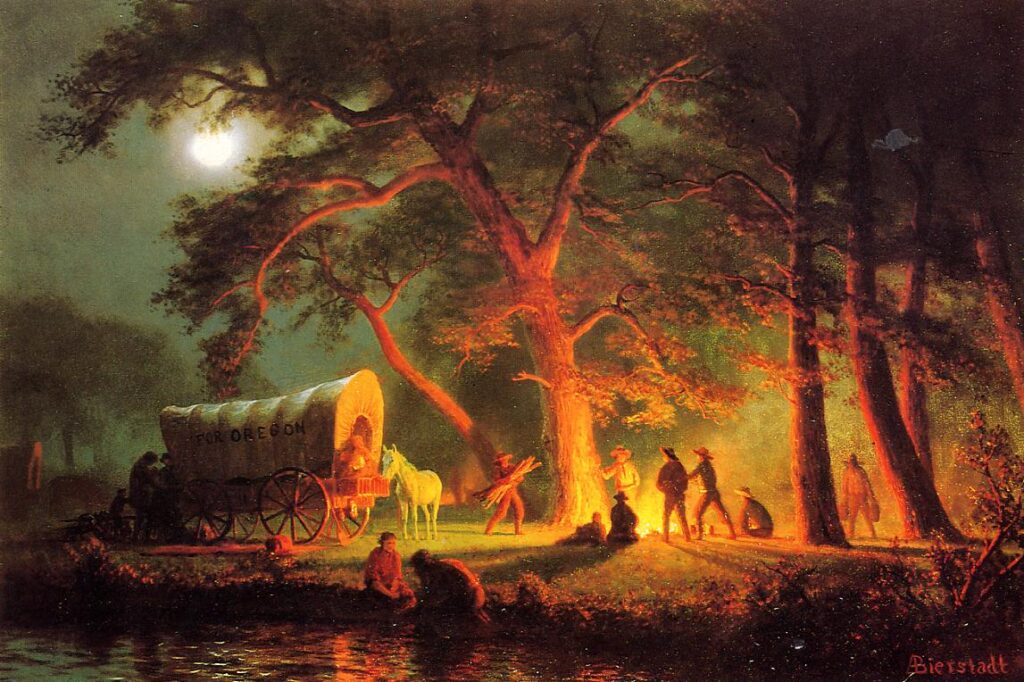

Only a small number of explorers, fur trappers, traders, and missionaries ventured far beyond the Mississippi River. These trailblazers drew a picture of the American West as a land of promise, a paradise of plenty, filled with fertile valleys and rich land. During the 1840s, tens of thousands of Americans began the process of settling the West beyond the Mississippi River. Thousands of families chalked GTT (“Gone to Texas”) on their gates or painted “California or Bust” on their wagons, and joined the trek westward. By 1850, pioneers had pushed the edge of settlement all the way to Texas, the Rocky Mountains, and the Pacific Ocean.

Reading Maps

Pathfinders

Before the nineteenth century, mystery shrouded the far West. Mapmakers knew very little about the shape, size, or topography of the land west of the Mississippi River. French, British, and Spanish trappers, traders, and missionaries had traveled the Upper and Lower Missouri River and the British and Spanish had explored the Pacific coast, but most of western North America was an unknown.

The first wave of exploration was touched off on July 5, 1803, when President Thomas Jefferson appointed his personal secretary, Meriwether Lewis, and William Clark to explore the Missouri and Columbia rivers as far as the Pacific. As a politician interested in the rapid settlement and commercial development of the West, Jefferson wanted Lewis and Clark to establish American claims to the region west of the Rocky Mountains, to gather information about furs and minerals in the region, and to identify sites for trading posts and settlements. As a scientist, the President also instructed the expedition to collect information covering the diversity of life in the West, ranging from climate, geology, plant growth, and the fossils of extinct animals to Indian religions, laws, and customs.

In 1806, the year that Lewis and Clark returned from their 8,000 mile expedition, a young Army lieutenant named Zebulon Montgomery Pike left St. Louis to explore the southern border of the Louisiana Territory, just as Lewis and Clark had explored the territory’s northern portion. Traveling along the Arkansas River, Pike saw the towering peak that bears his name. He and his party then traveled into Spanish territory along the Rio Grande and Red Rivers. Pike’s description of the wealth of Santa Fe brought American traders to the region.

Pike’s report of his expedition, published in 1810, helped to create one of the most influential myths about the Great Plains. The myth that this region was nothing more than a “Great American Desert,” a treeless and waterless land of dust storms and starvation.

This image of the West as a region of savages, wild beasts, and deserts received added support from another government-sponsored expedition, led by Major Stephen H. Long in 1820. Long’s report described the West as “wholly unfit for cultivation” and “uninhabitable by a people depending upon agriculture for their subsistence.” This report helped retard western settlement for a generation.

The view of the West as a dry, barren wasteland was not fully offset until the 1840s when another government-sponsored explorer, John C. Fremont, mapped much of the territory between the Mississippi Valley and the Pacific Ocean. His glowing descriptions of the West as a paradise of plenty captivated the imagination of many Midwestern families who, by the 1840s, were eager for new lands to settle.

Mountain Men

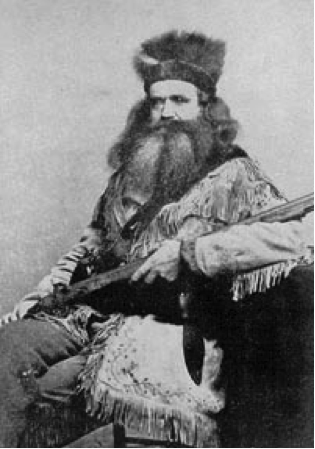

Traders and trappers were more important than government explorers in opening the West to white settlement. The “mountain men” blazed the great westward trails through the Rockies and Sierra Nevada Mountains and stirred the popular imagination with stories of redwood forests, geysers, and fertile valleys in California and Oregon. These men also undermined the ability of the western Indians to resist white incursions by encouraging intertribal warfare, making Indians dependent on American manufactured goods, killing off the animals that provided their subsistence, distributing alcohol, and spreading disease.

When Lewis and Clark completed their expedition, they brought back reports of rivers and streams in the northern Rockies teeming with beaver and otter. Fur traders and trappers quickly followed in their footsteps. The life of the mountain men was difficult, dangerous, and violent. One trapper in five died on the trails. Trappers faced stiff competition from the British Hudson’s Bay Company, which in 1824 established a fort on the banks of the Columbia River in Oregon and sent brigades of traders into the northern Rocky Mountains to search for pelts.

The western fur trade lasted only until 1840. Beaver hats for gentlemen went out of style in favor of silk hats, bringing the romantic era of the mountain man, dressed in a fringed buckskin suit, to an end. Fur bearing animals had been trapped out, and profits from the trade fell steeply. Instead of hunting furs, some trappers became scouts for the United States army or pilots for the wagon trains that began to carry pioneers to Oregon and California.

Trailblazing

The Santa Fe and Oregon Trails were the two principal routes to the Far West. William Becknell, an American trader, opened the Sante Fe Trail in 1821. Ultimately, the trail tied the New Mexican Southwest economically to the rest of the United States and hastened American penetration of the region.

On September 1, 1821, Becknell left Arrow Rock, Missouri, with a band of men and $300 worth of goods on pack animals. Two months and nearly 800 miles later his caravan arrived in Santa Fe. During the journey, Becknell had been forced to drink the blood from a mule’s ear and the contents of a buffalo’s stomach to survive when he could find no water. The Santa Fe Trail served primarily commercial functions. Mexican settlers in Santa Fe purchased cloth, hardware, glass, books, and the region’s first printing press. On their return east, American traders carried Mexican blankets, beaver pelts, wool, mules, and Mexican silver coins.

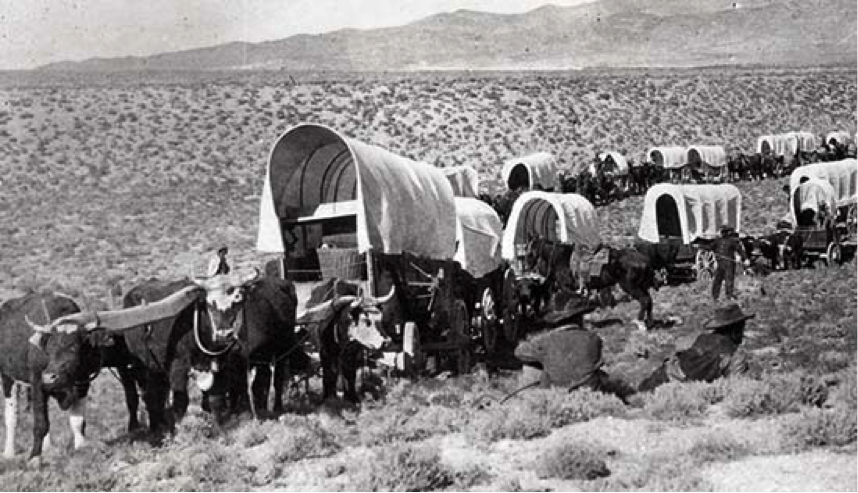

In 1811 and 1812, fur trappers marked out the Oregon Trail, the longest and most famous pioneer route in American history. Travel on the Oregon Trail was a tremendous test of human endurance. The journey by wagon train took six months. Settlers encountered prairie fires, sudden blizzards, and impassable mountains. Cholera and other diseases were common, and food, water, and wood were scarce. Only the stalwart dared brave the physical hardship of the westward trek.

Pioneers

During the early 1840s, thousands of pioneers headed westward toward California and Oregon. In 1841, the first party of 69 pioneers left Missouri for California, led by an Ohio schoolteacher named John Bidwell. The members of the party knew little about western travel: “We only knew that California lay to the west.” The hardships the party endured were nearly unbearable. They were forced to abandon their wagons and eat their pack animals, “half roasted, dripping with blood.”

Who were these pioneers? What forces drove them to push westward?

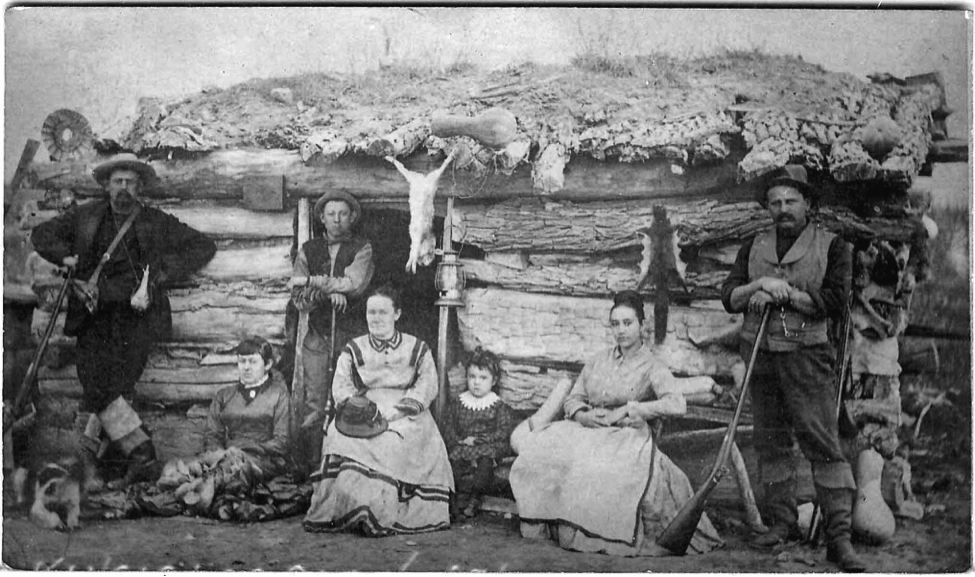

The rugged pioneer life was not a new experience for most of these early western settlers. Most of the pioneers who migrated to the Far West came from the states that border the Mississippi River: Missouri, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Illinois. These states had only recently acquired statehood: Louisiana in 1812, Illinois in 1818, Missouri in 1821, and Arkansas in 1836.

Pioneering was a familiar experience for many of these people. Either they or their parents had already moved several times before reaching the Mississippi Valley. Mark Twain vividly described the kinds of men he had seen while growing up in Hannibal, Missouri: “Rude, uneducated, brave, suffering terrific hardships with sailor-like stoicism; heavy drinkers…heavy fighters, reckless fellows, every one, elephantinely jolly, foul witted, profane; profligal of their money…yet in the main, honest, trustworthy, faithful to promises and duty, and often picaresquely magnanimous.”

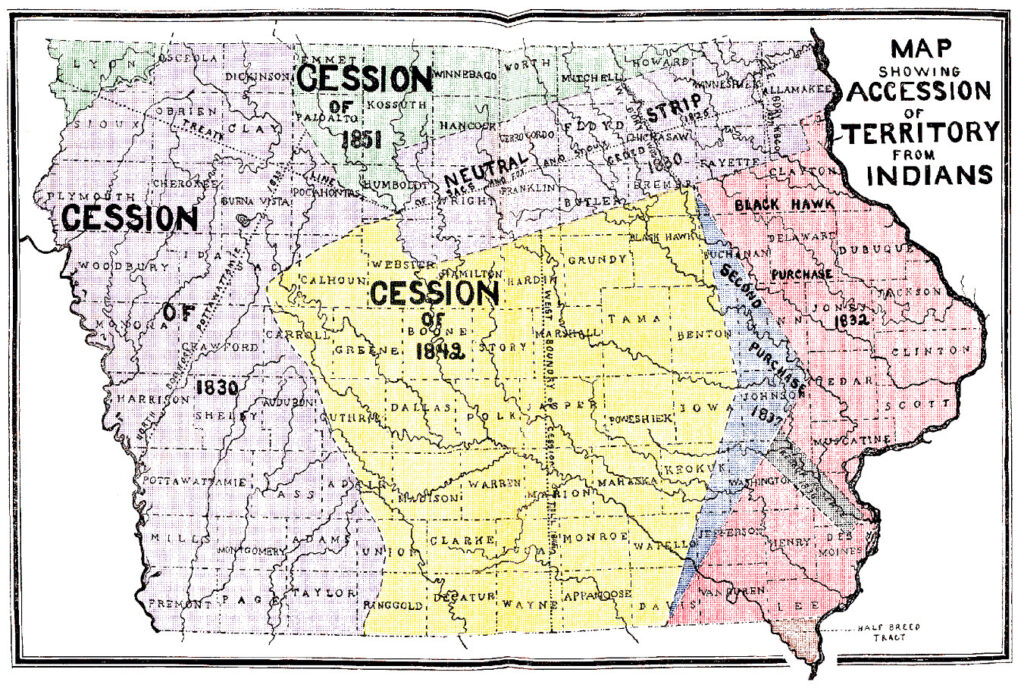

The Mississippi Valley was filled with restless men and women, thirsty for adventure and eager to better themselves. In 1833, when Iowa was cleared of Indians and opened to settlement, thousands of families pulled up stakes and poured into the area.

“Go West … and Grow up with the Country”

In 1854 Horace Greeley, a New York newspaper editor, gave Josiah B. Grinnell a famous piece of advice. “Go West, young man, and grow up with the country.” Grinnell took Greeley’s advice, moved west, and later founded Grinnell, Iowa. Before 1830, Iowa was Indian land, occupied by the Sauk, Fox, Missouri, Pottowatomi, and other Indian tribes. The defeat of the Sauk and Fox Indians in the Black Hawk War in 1832 opened the first strip of Iowa to settlement. By 1840, Iowa’s population had risen to 40,000.

Because no government land office was established in Iowa until 1838, many early settlers were squatters who set up farms on land that they did not own. Because they had cleared the land and built houses, they believed that the federal government would give them the right to purchase the land at minimum prices when it came up for sale. Unfortunately, later settlers known as “claim-jumpers” tried to take the squatters land away by outbidding them at public auctions or taking over their land when a family went to town for supplies. Squatters formed more than 100 land-claims associations—extra-legal associations of local settlers—to eliminate competitive bidding and protect their holdings when the lands were offered for sale. In 1841, Congress passed a law that recognized squatter’s rights. The Pre-emption Bill provided that squatters who lived on and made improvements on surveyed government land could have the first option to buy up to 160 acres for $1.25 an acre.

At the same time that settlers poured into Iowa, other pioneers migrated to Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. Lumberjacks and miners were the first to arrive. Soon they were followed by farmers and traders. Even before this northern tier of states was filled, people in the Mississippi Valley leapfrogged treeless prairies, deserts, and mountains for the West Coast.

It was not until the 1870s and 1880s that pioneers settled on the prairies of Nebraska, Montana, and the Dakotas, because these areas were much drier and settlers preferred well-watered regions near rivers and streams. Only when this land was no longer available did pioneers edge onto the more difficult prairies, using windmills to pump water and unplowed land or sod for their houses. Most of this settlement would occur after the Civil War.

Life on the Trail

Each spring, pioneers gathered at Independence and St. Joseph, Missouri, and Council Bluffs, Iowa, to begin a 2,000 mile journey westward. For many families, the great spur for emigration was economic: the financial depression of the late 1830s, accompanied by floods and epidemics in the Mississippi Valley. Said one woman: “We had nothing to lose, and we might gain a fortune.” Between 1841 and 1867, more than 350,000 trekked along the overland trails.

Most pioneers traveled in family units. At first, pioneers tried to maintain the rigid sexual division of labor that characterized early nineteenth century America. Men drove the wagons and livestock, stood guard duty, and hunted buffalo and antelope for extra meat. Women got up at four in the morning, collected wood and “buffalo chips” (animal dung used for fuel), hauled water, kindled campfires, kneaded dough, and milked cows. At the end of the day, men expected women to fix dinner, make up beds, air out the wagons to prevent mildew, wash the clothes, and tend the children.

The demands of the journey forced a blurring of gender role distinctions for women, who performed many chores previously reserved for men. They drove wagons, yoked cattle, and loaded wagons. Some men even did things such as cooking, they previously would have regarded as women’s work.

Accidents, disease, and sudden disaster were ever-present dangers. Children fell out of wagons, oxen hauling wagons became exhausted and died, and diseases such as typhoid, dysentery, and mountain fever killed many pioneers. Emigrant parties also suffered devastation from buffalo stampedes, prairie fires, and floods. Pioneers buried at least 20,000 emigrants along the Oregon Trail.

Still, despite the hardships of the experience, few emigrants ever regretted their decision to move west. As one pioneer put it:

Those who crossed the plains…never forgot the ungratified thirst, the intense heat and bitter cold, the craving hunger and utter physical exhaustion of the trail….But there was another side. True they had suffered, but the satisfaction of deeds accomplished and difficulties overcome more than compensated and made the overland passage a thing never to be forgotten.

Limiting Births in the Early Republic

Listen to a podcast about limiting births in the early republic.