Westward Expansion & the American Character and Self-Image

The Donner Party

Early in April, 1846, 87 pioneers led by George Donner, a well-to-do 62-year-old farmer, set out from Springfield, Illinois, for California. Like many emigrants, they were ill-prepared for the dangerous trek. The pioneers’ 27 wagons were loaded with fancy foods, liquor, built-in beds and stoves.

On July 20, at Fort Bridger, Wyoming, the party decided to take a shortcut. Lansford W. Hastings, a California booster, had suggested in a guidebook that pioneers could save 400 miles by cutting south of the Great Salt Lake. Hastings himself had never taken his own shortcut. He was trying to overthrow California’s weak Mexican government and hoped to bring in enough emigrants to start a revolution.

Soon huge boulders, arid desert, and dangerous mountain passes slowed the expedition to a crawl. During one stretch, the party traveled only 36 miles in 21 days. A desert crossing that Hastings said would take two days actually took six days and nights.

Twelve weeks after leaving Fort Bridger, the Donner party reached the eastern Sierra Nevada Mountains and prepared to cross Truckee Pass, the last remaining barrier before they arrived in California’s Sacramento Valley. On October 31, they climbed the high Sierra ridges in an attempt to cross the pass, but five-foot high snow drifts blocked their path.

Trapped, the party built crude tents and tepees, covered with clothing, blankets, and animal hides. To survive, the Donner party was forced to eat mice, rugs, and even shoes. In the end, the surviving members of the party escaped starvation only by eating the flesh of those who died.

In mid-December, a group of twelve men and five women made a last-ditch effort to cross the pass to find help. They took only a 6-day supply of rations, consisting of finger-sized pieces of dried beef—two pieces a person per day. During a severe storm, two of the group died. The surviving members of the party “stripped the flesh from their bones, roasted and ate it, averting their eyes from each other, and weeping.” More than a month passed before seven frost-bitten survivors reached an American settlement. By then, the rest had died and two Indian guides had been shot and eaten.

Relief teams immediately sought to rescue the pioneers still trapped near Truckee Pass. During the winter, four successive rescue parties broke through and brought out the survivors. The situation that the rescuers found was unspeakably gruesome. Thirteen were dead. Surviving members of the Donner party were delirious from hunger and overexposure. One survivor was found in a small cabin next to a cannibalized body of a young boy. Of the original 87 members of the party, only 47 survived.

Westward Expansion and the American Character

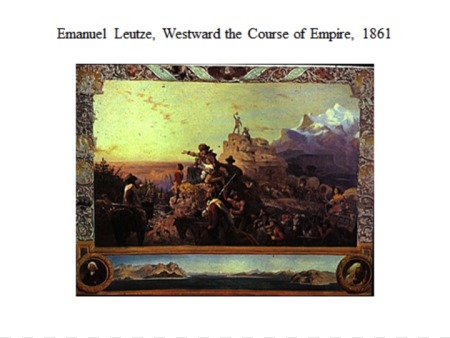

American history is, in large measure, the story of the movement into new frontiers: first into New Hampshire and Maine, then into the of backwoods Virginia, Kentucky, and Ohio, western Pennsylvania, and New York, and later into the Gulf Coast, the Midwest, Texas, California, and the Pacific Northwest.

Today, those new frontiers lie in outer space and cyberspace.

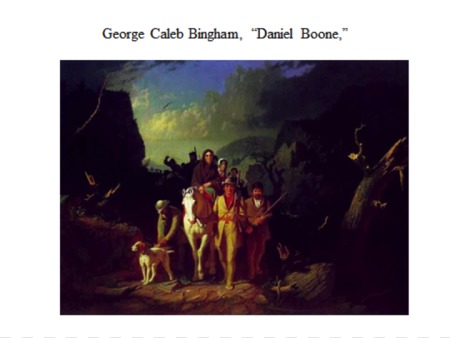

The settlement of the frontier is one of the overarching themes of American history and many of the country’s most memorable figures—from Daniel Boone to the Mountain Men and David Crockett—were associated with the opening of new frontiers.

And then, the physical frontier closed.

The Census of 1890 announced that the Western frontier was now closed. There was no clear line beyond which settlement had not taken place. Three years later, at the World’s Columbia Exposition held to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s voyage of discovery, a young historian named Frederick Jackson Turner argued that the closing of the frontier marked the end of an era of U.S. history. In his view, it had been the settlement of the frontier that had shaped the nation’s character. It had produced a people who were self-reliant, ambitious, democratic, and egalitarian.

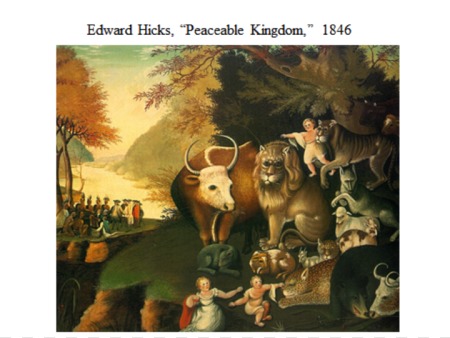

The frontier took the settler with his European dress and manner. The frontier “stripped off the garments of civilization” and created a new kind of human being. “The outcome,” according to Turner, “is not the old Europe.” It is a “new product that is American”— less class conscious and pretentious than those in Europe.

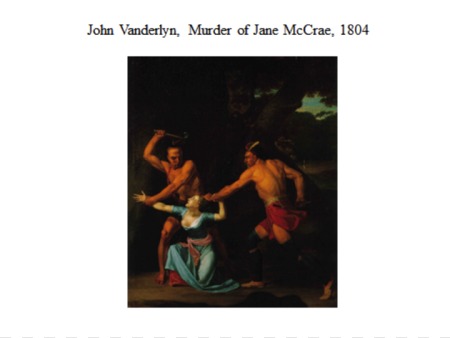

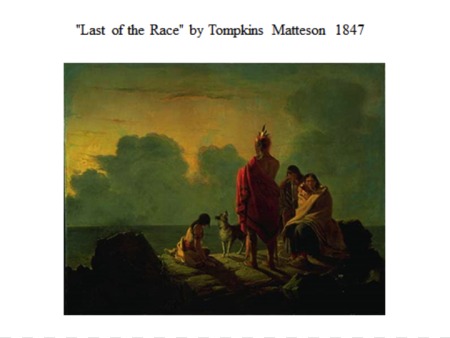

Turner’s critics did not dismiss the importance of the frontier experience, but argued that some of its consequences were less positive. The story of westward expansion, in the eyes of Turner’s critics, was a story of imperial expansion, displacement, and occupation. It pitted rapacious Americans against Indians and Mexicans. The West, in this view, was stolen from its original inhabitants that were reduced to colonial subordination.

History Through…

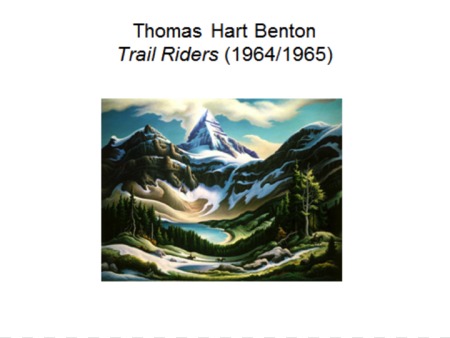

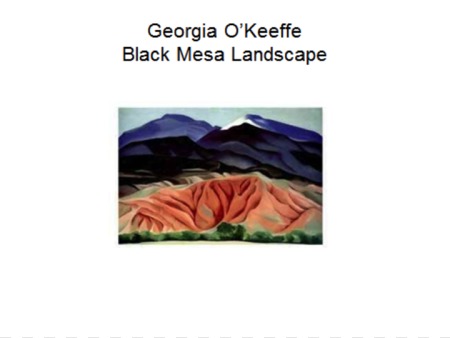

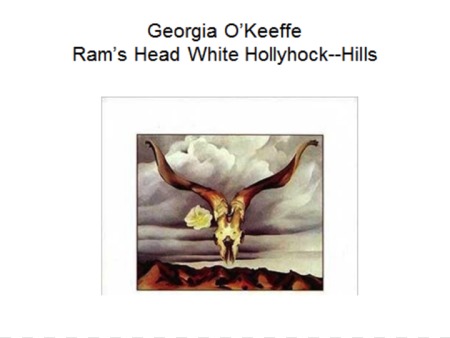

…The Western Landscape in Art

The West occupies a singularly important place in the American imagination. Just think of the references in “America the Beautiful”:

O beautiful for spacious skies,

For amber waves of grain,

For purple mountain majesties

Above the fruited plain!

America! America!

God shed his grace on thee…

The Western landscape symbolizes American identity.

Sight and Sound

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.