The Gold Rush

The Political Crisis of the 1840s

The question of slavery burst into the public spotlight one summer evening in 1846. Congressman David Wilmot, a Pennsylvania Democrat, introduced an amendment, known as the Wilmot Proviso, to a war appropriations bill. The proviso forbade slavery in any territory acquired from Mexico. Throughout the North, thousands of working men, mechanics, and farmers feared that free workers would be unable to successfully compete against slave labor. “If slavery is not excluded by law,” said one Northern congressman, “the presence of the slave will exclude the laboring white man.”

Southerners denounced the Wilmot Proviso as “treason to the Constitution.” President Polk tried to quiet the debate between “Southern agitators and Northern fanatics” by assuring moderate Northerners that slavery could never take root in the arid Southwest, but his efforts were to no avail. With the strong support of Westerners, the amendment passed the House twice, but was defeated in the Senate. Although the Wilmot Proviso did not become law, the issue it raised—the extension of slavery into the western territories—continued to contribute to the growth of political factionalism.

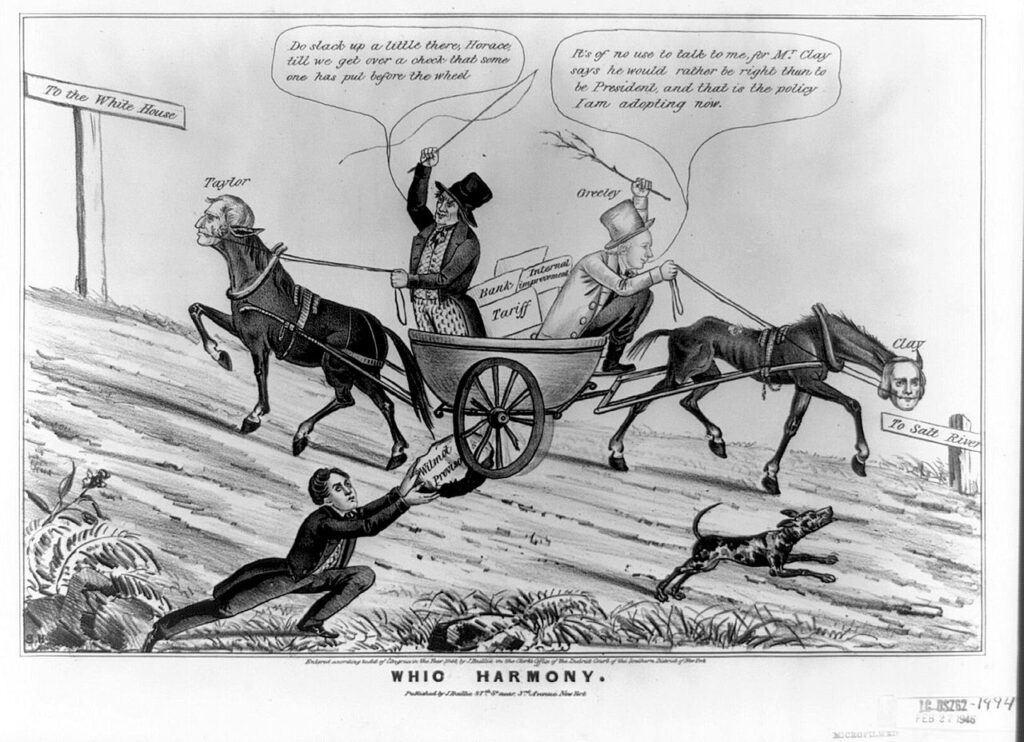

Growing sectional tensions were also evident in the founding of the Free Soil Party in 1848. This sectional party opposed the westward expansion of slavery and favored free land for western homesteaders. Under the slogan “free soil, free speech, free labor, and free men,” the party nominated ex-President Martin Van Buren as its Presidential nominee in 1848 and polled 291,000 votes. This was enough to split the Democratic vote and throw the election to Whig candidate Zachary Taylor.

Up until the last month of 1848, the debate over slavery in the Mexican cession seemed academic. Most Americans thought of the newly acquired territory as a wasteland filled with “broken mountains and dreary desert.” William Tecumseh Sherman summed up prevailing sentiment when he said he would not trade two eastern counties for all the Far West. Then in his farewell address, President Polk electrified Congress with the news that gold had been discovered in California–and suddenly the question of slavery was inescapably important.

The Gold Rush

On January 24, 1848, less than ten days before the signing of the peace treaty ending the Mexican War, James W. Marshall, a 36-year old carpenter and handyman, noticed several bright bits of yellow mineral near a sawmill that he was building for John A. Sutter, a Swiss-born immigrant who owned one of the great ranches that dotted California’s Sacramento Valley. To test if the bits were “fool’s gold,” which shatters when struck by a hammer, or gold, which is malleable, Marshall “tried it between two rocks, and found that it could be beaten into a different shape but not broken.” He told the men working with him: “Boys, by God, I believe I have found a gold mine.”

On March 15, a San Francisco newspaper, The Californian, printed the first account of Marshall’s discovery. Within two weeks, the paper had lost its staff and was forced to shut down its printing press. In its last edition it told its readers: “The whole country, from San Francisco to Los Angeles…resounds with the sordid cry of Gold! Gold! Gold! while the field is left half-planted, the house half-built, and everything neglected but the manufacture of picks and shovels.”

In 1849, 80,000 men arrived in California—half by land and half by ship around Cape Horn or across the Isthmus of Panama. Only half were Americans. The rest came from Britain, Australia, Germany, France, Latin America, and China. Platoons of soldiers deserted. Sailors jumped ship. Husbands left wives. Apprentices ran away from their masters. Farmers and business people deserted their livelihoods. By July, 1850, sailors had abandoned 500 ships in San Francisco Bay. Within a year, California’s population had swollen from 14,000 to 100,000. The population of San Francisco, which stood at 459 in the summer of 1847, reached 20,000 within a few months.

During the early years of the Gold Rush, men traveled alone to California. Few women arrived during the early years—for example, only 700 in 1849. In 1850, women made up only eight percent of California’s population. In mining areas, they made up less than two percent.

The gold rush transformed California from a sleepy society into one that was wild, unruly, ethnically-diverse, and violent. Philosopher Josiah Royce, whose family arrived in the midst of the gold rush, declared that the Californian was “morally and socially tried as no other American ever has been tried.” In San Francisco alone, there were more than 500 bars and 1,000 gambling dens. In the span of 18 months, the city burned to the ground six times.

There were a thousand murders in San Francisco during the early 1850s, but only one conviction. Forty-niners, the nickname of the immigrants who traveled to California in 1849, slaughtered Indians for sport, drove Mexicans from the mines on penalty of death, and sought to restrict the immigration of foreigners, especially the Chinese. Since the military government was incapable of keeping order, leading merchants formed vigilance committees, which attempted to rule by lynch law and the establishment of “popular” courts.

The sudden influx of tens of thousands of immigrants into California raised a question that would disrupt U.S. politics: Would California become a slave state or a free state, upsetting the sectional balance of power?

Conclusion

In the span of just five years, the United States had increased in size by a third and acquired an area that now includes the states of Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Texas, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. First to carry the American flag into the Far West were a small coterie of government explorers, fur trappers, traders, and missionaries. These were the people who found the fertile valleys and great forests of the West, marked trails, and stirred the imagination of many Midwesterners eager for adventure. Ranchers, farmers, and tradesmen followed, taking the overland trails across treeless plains, dangerous mountains, and arid deserts, into Texas, Oregon, and California. The United States acquired Texas through annexation. Negotiations with Britain gave the United States half of the Oregon Country. California and the great Southwest became part of the United States as a result of war with Mexico.

The exploration and settlement of the Far West is one of the great epics of nineteenth century history. But, America’s dramatic territorial expansion also created severe problems. In addition to providing the United States with its richest mines, greatest forests, and most fertile farm land, the Far West intensified the sectional conflict between the North and South and raised the fateful and ultimately divisive question of whether slavery would be permitted in the western territories. Could democratic political institutions resolve the question of slavery in the western territories? That question would dominate American politics in the 1850s.

The rapid influx of miners into California led to a frenzy of price gouging. A bottle of molasses or a pint-and-a-half of vinegar sold for a dollar. Pork was $5 a pound. Eggs went for as much as $4 a dozen. Toothpicks were sold for 50 cents apiece. The value of real estate exploded. A lot in San Francisco purchased in 1847 for $16.50 sold for $6,000 in the spring of 1848 and was later resold for $48,000.

The gold rush era in California lasted less than a decade. By the mid-1850s, the lone miner who prospected for gold with a pick, a shovel, and a wash pan was already an anachronism. Mining companies using heavy machinery replaced the individual prospector. Systems of dams exposed whole river bottoms. Drilling machines drove shafts 700 feet into the earth. Hydraulic mining machines blasted streams of water against mountainsides.

By 1860, the romantic era of California gold mining was over. Prospectors had found more than $350 million worth of gold. Certainly, some fortunes were made—one prostitute claimed to have made $50,000 after a year’s work—but few struck it rich.

Ironically, the two men most responsible for the gold rush died penniless. James W. Marshall, who discovered the first gold bits, eventually became a blacksmith in Kelsey, California, and died in poverty. John A. Sutter, on whose ranch gold was discovered, was left bankrupt as a result of the gold rush. His workmen deserted to hunt gold, his crops rotted in the fields, and forty-niners trespassed on his land and stole his cattle. He died in 1880 in Pennsylvania while lobbying Congress to reimburse him for the losses he had suffered because of the discovery of gold on his land