Introducing: Westward Expansion

Zorro: Fiction and Fact

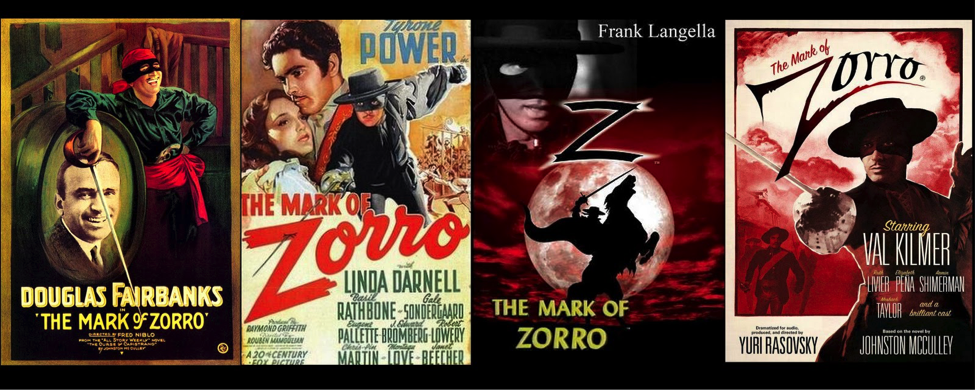

He was Hollywood’s first swashbuckling hero. He wore a mask, wielded a cape and a sword with panache, and announced his presence by slashing the letter Z on a wall. Like the legendary English outlaw Robin Hood, Zorro robbed from the rich and gave to the poor–but with a crucial difference: he was Hispanic. In more than a dozen feature films and a long-running Walt Disney television series, Don Diego Vegas, the son of a prominent wealthy California alcalde (administrator and judge), adopts the secret identity of Zorro, robs tax collectors, and returns the money to California’s peasants.

Zorro was a fictional character created by a popular novelist named Jonathan Culley. But the figure he portrayed—the social bandit protecting the interests of Mexicans and Mexican Americans in the Southwest—was based on reality. In Texas and California, figures like Juan Nepomuceno Cortina and the legendary Joaquín Murieta, turned to banditry as a way to resist exploitation and avenge injustice. Though called bandidos, they did not rob banks or stage coaches. Instead, they sought to protect the economy and the traditional rights of Mexicans and Mexican Americans.

Until recently, American popular culture presented the story of America’s westward expansion largely from the perspective of white Americans. Countless western novels and films depicted the westward movement primarily through the eyes of explorers, missionaries, soldiers, trappers, traders, and pioneers.

Theodore Roosevelt captured this perspective in a book entitled The Winning of the West, an epic tale of white civilization conquering the western wilderness. But there are other sides to the story. To properly understand America’s surge to the Pacific, one must understand it from multiple perspectives, including the viewpoint of the people who already inhabited the region: Mexicans and Native Americans.

Spanish America

When white Americans ventured westward, they did not enter uninhabited land. Until 1821, Spain ruled the area that now includes the present-day states of Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah. Spanish explorers, priests, and soldiers first entered the area in the early sixteenth century, half a century before the first English colonists arrived at Jamestown.

Unlike England, however, Spain did not actively encourage migration or economic development in its northern empire. Spain restricted manufacturing, trade, and discouraged migration. In 1821, the year Mexico gained its independence, Spanish settlement was concentrated in just four areas:

- Southern Arizona

- California Coast

- New Mexico

- Central Texas

Santa Fe, Spain’s largest northern settlement, had 6,000 Spanish inhabitants, and San Antonio a mere 1,500.

Nevertheless, Spain left a lasting imprint on the region. Such institutions as the rodeo and the cowboy had their roots in Spanish culture. The American cowboys borrowed their clothing, customs, and even the songs of earlier Mexican vaqueros. Like the vaqueros, the cowboy used a rope known as a lariat (reata) to corral cattle and utilized a special saddle (now known as a “western” saddle) with a horn. The cowboys also borrowed the vaqueros’ clothing, including the wide-brimmed hat, the high-heel pointed toe boots, and leather leggings, known as chaps (short for chaparreras), that protected the cowboy’s legs. Their nickname, wrangler, came from a Spanish word, catallerango. Many cowboy songs, like “The Streets of Laredo,” were actually translations of Mexican ballads.

Such place names as Los Angeles and San Diego also reflect the region’s Spanish heritage. To this day, Spanish architecture—adobe walls, tile roofs, wooden beams, and intricate mosaics—continues to characterize the Southwest.

By introducing horses and livestock, Spanish colonists and missionaries transformed the Southwestern economy and the area’s physical appearance. As livestock devoured the region’s tall native grasses, a distinctly new southwestern environment arose: one of cactus, sagebrush, and mesquite.

Impact of the Mexican Revolution

In 1810, a Mexican priest, Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, led a short-lived revolt against Spanish rule. It was the beginning of Mexico’s struggle for independence, which was achieved in 1821.

The collapse of Spanish authority opened the Southwest to American economic penetration and settlement. By 1848, white Americans made up about half of California’s non-Native American population.

Mexican independence also led to the demise of the California mission system. Under this system, priests forced Native Americans to live in mission communities, where they were forced to work in weaving, blacksmithing, candlemaking, leatherworking, and agriculture.

In 1833 and 1834, the Mexican government confiscated California’s mission properties and sold or gave the property away to private landowners called rancheros. These ranchos were run like feudal estates. The death rate of Native Americans who worked on the ranchos was twice that of Southern slaves.