The Columbian Exchange: Disease & the Environment

Disease

Imagine if the population of New York City suddenly dropped by 50 to 90 percent from 8.4 million to as little as 840,000. That is what happened to the Indian peoples of Mexico, Brazil, Peru, the Caribbean, and North America in the first centuries after 1492.

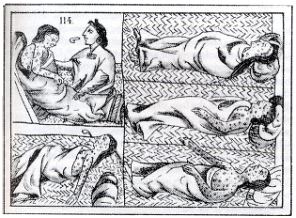

At its very worst, from 1347 to 1351, the Black Death killed one-third of the people in Europe. But what happened in the New World was far worse. Smallpox, chickenpox, typhoid, bubonic plague, diphtheria, influenza, mumps, measles, and whooping cough, later followed by cholera, malaria and scarlet fever, radically reduced the size of the indigenous population.

The peoples of the Western Hemisphere and of Oceania had no inherited or acquired immunity to the diseases of Europe, Africa or Asia. Many had come to the New World in small bands, too small to carry infectious diseases. These people also did not keep herds of animals, which might have allowed pathogens to flourish.

How Do We Know?

Impact on the Indigenous Population

Alexis de Tocqueville, a French observer who visited the United States in the 1830s, asserted that the North America, prior to Columbus, was an “empty continent…awaiting its [new] inhabitants.” The U.S. Bureau of the Census, writing in 1894, took a similar position. “Investigation shows,” the Bureau concluded, “that the aboriginal population within the present United States at the beginning of the Columbian period could not have exceeded much over 500,000.”

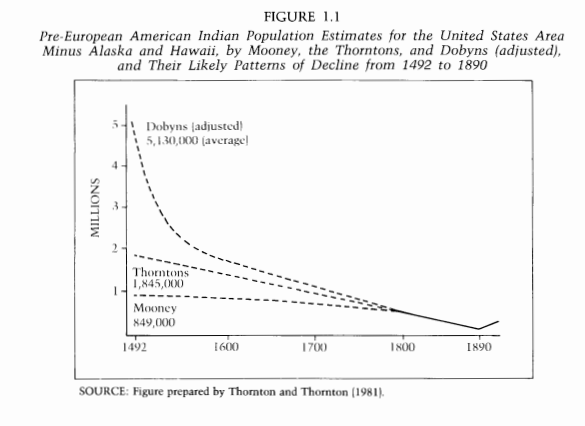

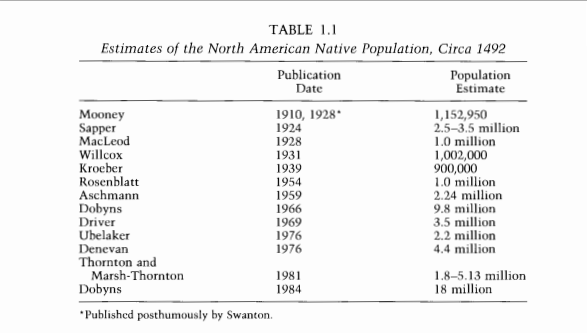

Current estimates of the Indian population north of Mexico are far higher, ranging from about two million to eighteen million, with the consensus at about seven million. There is no disagreement, however, that the size of the indigenous population fell sharply after 1492. By 1900, the Indian population in the United States, Canada, and Greenland had declined to just 375,000, the result of disease, disruption of social systems, exploitation, and warfare—all contributed to the decline in the size of the indigenous population.

Much of the decline resulted from disease: smallpox, measles, the bubonic plague, cholera, typhoid, diphtheria, scarlet fever, various forms of influenza and whooping cough, malaria, and yellow fever as well as some venereal diseases. But colonial contact itself had a powerful impact. Such factors as displacement and mass relocation, forced labor, warfare, and changes in the ecology not only sharply increased death rates but reduced birth rates.

How do we know? After all, systemic censuses only appeared much later, with the first national census counts taking place in Sweden in 1749, the United States in 1790, and Britain and France in 1801. China did not conduct its first census until 1953.

One source of information lies in the estimates made by explorers, missionaries, soldiers, and other observers about specific Indian tribes. This was the method employed by James Mooney, a Smithsonian ethnologist. Assuming that the observers exaggerated the size of the Indian population, he took their lowest estimates he could find. His tribe-by-tribe estimate, published in 1928, concluded that there were 1.15 million Indians north of Mexico in 1492.

Another approach is to estimate the population density that specific geographical areas could support. This was how the anthropologist Alfred Kroeber arrived at his 1934 estimate that the Indian population north of the Rio Grande River was about 4.2 million in 1492.

More recently, scholars have tapped a wide variety of sources to reconstruct the size of the pre-contact Indian population. These include counts of the number of Indian warriors, baptismal and tax records, accounts of epidemics, acreage devoted to raising corn and beans to estimate food supply, and even the number of canoes. The result was to sharply raise the estimated population.

To Learn More:

Lessons of History

The Environmental Consequences of the Columbian Exchange

The Columbian Exchange had profound consequences for the natural environment.

Wildlife was extraordinarily abundant at the time of European contact. Passenger pigeons darkened the skies. Deer congregated by the hundreds. A single net in Virginia caught 5,000 sturgeons. Observers reported seeing crabs and oysters a foot in length, and lobsters as large as five or even six feet long.

The area north of Mexico was not unbroken forest. East of the Mississippi, Indian peoples cleared fields with fire, resulting in an environment consisting of widely spaced trees and relatively few shrubs, providing room for deer, elk, porcupine, quail, rabbits, and turkeys. The abundance of game also encouraged such predators as eagles, foxes, hawks, and wolves.

Many indigenous peoples east of the Mississippi River plowed and sowed crops including corn, potatoes, pumpkin, and squash. In the southwest, the Anasazi devised a complex system of dikes and dams to water fields.

The arrival of Europeans changed the face of the land. The newcomers introduced grasses, plants, and weeds including clover, dandelions and ragweed. They also chopped down trees to clear fields and used the wood to heat their homes, cook their food, and construct their buildings.

The introduction of cattle, pigs, and sheep, too, reshaped the natural environment. Cattle, pigs, sheep, and horses required even more land than farming, and encouraged geographical expansion These animals devoured Indian corn as well as many grasses and shrubs, and compacted the earth under their hooves. The effect of the clearing of land and the compression of the soil was to make the land more susceptible to flooding and erosion.

The Europeans mistakenly believed that the Indians had no conception of land ownership since the Indians generally held land in common and tended not to establish permanent settlements. Europeans, in contrast, tended to fence in the land to mark off individual landholdings and to treat land as property that could be bought and sold. The view that Indians did not have a conception of ownership made it easier for European settlers to claim the land for themselves.

There would also be a huge European demand for the furs of beaver, foxes, martens, muskrats, and otters (and later for buffalo hides),which dramatically reduced these animals’ numbers.

After 1492, the human ability to exploit the natural environment greatly increased. Over time, many fur-bearing animals would be hunted to near extinction. Sea creatures, too, especially cod and whales, were radically reduced in numbers.