Three Worlds Collide

Seven Decisive Decades

The period stretching from 1450 to 1520 witnessed many of the most important events in European history.

Lessons of History

The Significance of 1492

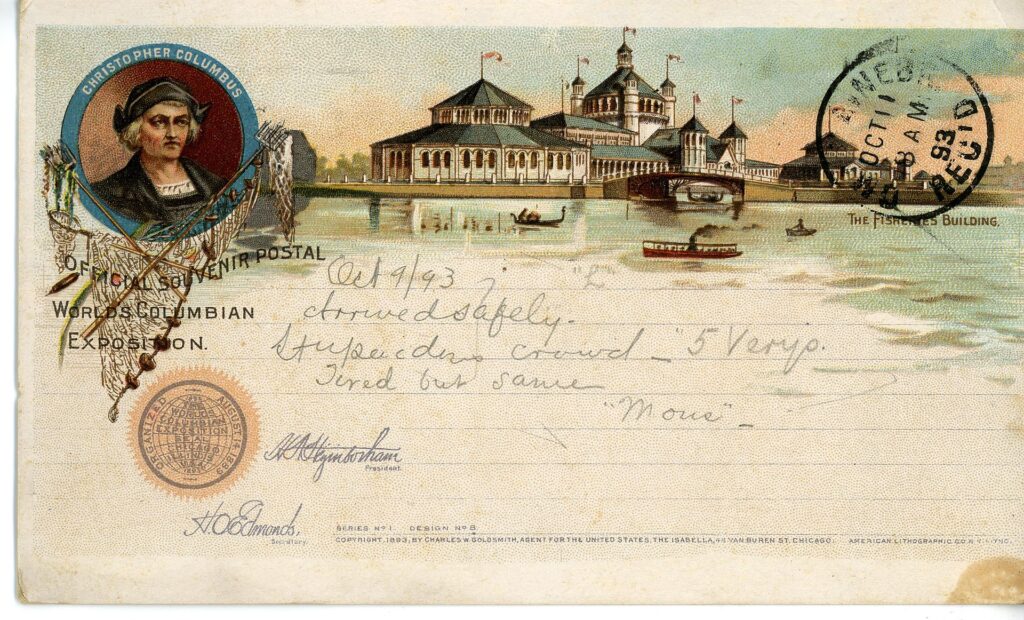

The four hundredth anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s “discovery of the New World” was commemorated with a massive “Columbian Exhibition” in Chicago in 1893. The exhibition celebrated Columbus as a man of mythic stature, an explorer, and a discoverer who carried Christian civilization across the Atlantic Ocean and initiated the modern age.

The five hundredth anniversary of Columbus’s first voyage of discovery was treated quite differently. Many peoples of indigenous and African descent identified Columbus with imperialism, colonialism, and conquest. The National Council of Churches adopted a resolution calling October twelfth a day of mourning for millions of indigenous people who died as a result of European colonization.

More than five hundred years after the first Spaniards arrived in the Caribbean, historians and the general public still debate Columbus’s legacy. Should he be remembered as a great discoverer who brought European culture to a previously unknown world? Or should he be condemned as a man responsible for an “American Holocaust,” a man who brought devastating European and Asian diseases to unprotected native peoples, disrupted the American ecosystem, and initiated the Atlantic slave trade? What is Columbus’s legacy—discovery and progress? Or slavery, disease and racial antagonism?

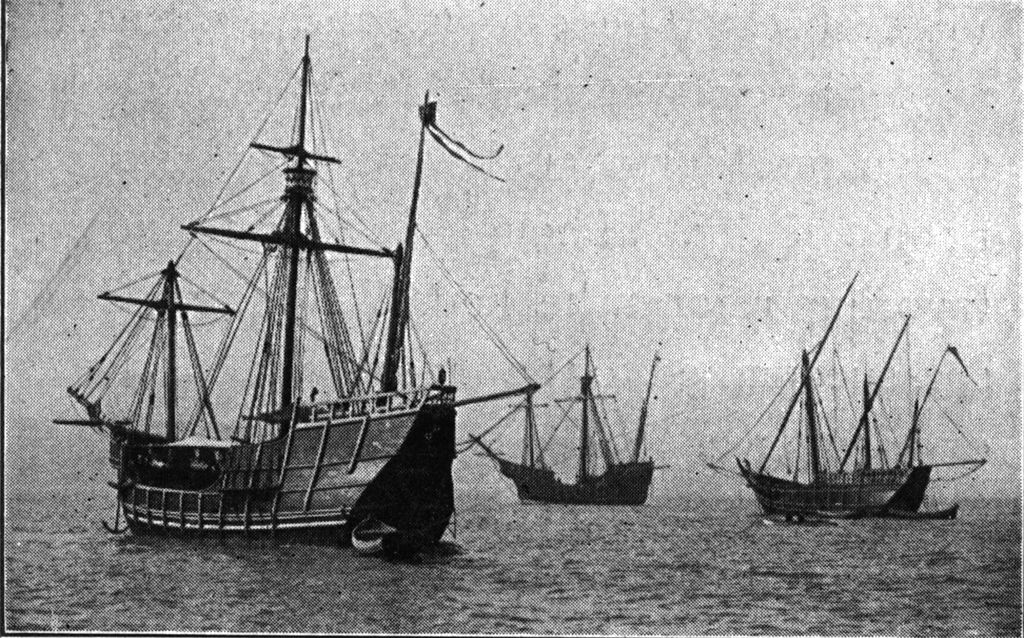

To confront such questions, one must first recognize that the encounter that began in 1492 among the peoples of the Eastern and Western Hemispheres was one of the truly epochal events in world history. This cultural collision not only produced an extraordinary transformation of the natural environment and human cultures in the New World, it also initiated far-reaching changes in the Old World as well.

New foods reshaped the diets of people in both hemispheres. Tomatoes, chocolate, potatoes, corn, green beans, peanuts, vanilla, pineapple, and turkey transformed the European diet, while Europeans introduced sugar, cattle, pigs, cloves, ginger, cardamom, and almonds to the Americas. Global patterns of trade were overturned, as crops grown in the New World—including tobacco, rice, and vastly expanded production of sugar—fed growing consumer markets in Europe.

Even the natural environment was transformed. Europeans cleared vast tracks of forested land and inadvertently introduced Old World weeds. The introduction of cattle, goats, horses, sheep, and swine also transformed the ecology as grazing animals ate up many native plants and disrupted indigenous systems of agriculture. The horse, extinct in the New World for 10,000 years, transformed the daily existence of many indigenous peoples. The introduction of the horse encouraged many farming peoples to become hunters and herders. Hunters mounted on horses were much more adept at killing game.

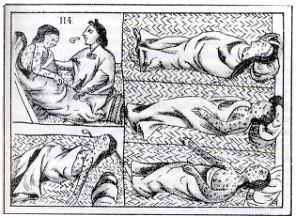

Death and disease were consequences of contact, too. Diseases against which Indian peoples had no natural immunities caused the greatest mass deaths in human history. Within a century of contact, smallpox, measles, mumps, and whooping cough had reduced indigenous populations by 50 to 90 percent. From Peru to Canada, disease reduced the resistance that Native Americans were able to offer to European intruders.

With the Indian population decimated by disease, Europeans gradually introduced a new labor force into the New World: enslaved Africans. Between 1502 and 1870, when the Atlantic slave trade was finally suppressed, ten to fifteen million Africans were shipped to the Americas.

Columbus’s voyage of discovery also had another important result: it contributed to the development of the modern concept of progress. To many Europeans, the New World seemed to be a place of innocence, freedom, and eternal youth. The perception of the New World as an environment free from the corruptions and injustices of European life would provide a vantage point for criticizing all social evils. So while the collision of three worlds resulted in death and enslavement in unprecedented numbers, it also encouraged visions of a more perfect future.

Columbus’s voyages represent one of the major discontinuities in human history. His voyages truly represented a historical watershed, with vast repercussions for all aspects of life in both the Old World and the New. The year 1492—perhaps more than any other year in modern world history—was a truly landmark moment, carrying enormous implications for the natural environment, for intellectual thought, and for the international economy.

History Through…

… Art: European Conception of the Other

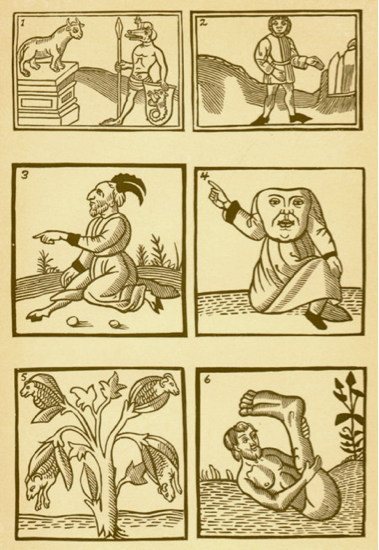

During the decade before 1492, as Columbus nursed a growing urge to sail west to the Indies, he studied old writers to find out what the world and its people were like.

He read the Ymago Mundi of Pierre d’Ailly, a French cardinal who wrote in the early fifteenth century, the travels of Marco Polo, and Sir John Mandeville, Pliny’s Natural History and the Historia Rerum Ubique Gestarum of Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini.

Columbus was not a scholarly man. Yet he studied these books, made hundreds of marginal notations in them and came out with ideas about the world that were characteristically simple and strong and sometimes wrong, the kind of ideas that the self-educated person gains from independent reading and clings to in defiance of what anyone else tries to tell him.

Among the most influential books was The Travels of Sir John Mandeville (1371). It purports to recount the author’s travels through Jerusalem, Egypt, Turkistan, India, China, and other places. Actually, it is a skillful compilation from the recorded travels of other people—e.g., Marco Polo, Ordoric of Pordenone, and William of Boldensele— into which Mandeville interpolated extravagant details of medieval lore.

Mandeville tells of islands whose inhabitants had the bodies of humans but the heads of dogs, of a tribe whose only source of nourishment was the smell of apples, of a people the size of pygmies whose mouths were so small that they had to suck all their food through reeds, and of a race of one-eyed giants who ate only raw fish and raw meat. All of this fantasy was interwoven with other geographical descriptions that were perfectly accurate.

Cinematic Encounters with Aliens

Many of Hollywood’s most popular science fiction films—from The Day the Earth Stood Still to E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial and Independence Day—examine encounters with aliens. In 1492, a “close encounter of the ‘third kind’” (physical contact) actually took place, as groups of people who had never known of each other’s existence collide.

Let’s take a look at how Hollywood and Europeans prior to 1492 imagined aliens.

Do Earthlings and aliens meet in peace, or do the aliens seek to enslave or exterminate the human race? Supposed sightings of flying saucers in 1947 ignited a frenzy of interest in Unidentified Flying Objects and aliens.

Since the sci-fi heyday of the 1950s—a decade which saw both the dawn of the real-world space age, and a continually escalating threat of global nuclear war—mainstream cinema has been somewhat obsessed with the subject of alien invasion, offering as it does the opportunity for audiences to reflect on real-world crises while reveling in escapist spectacle.

The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951)

An alien named Klaatu arrives in Washington, D.C. in a flying saucer. Even though he and his companions announce that they have come in peace, their arrival triggers panic. A nervous soldier shoots Klaatu, but he comes back to life and delivers a message from the Galactic Federation: Either Earth must live in peace under the rule of Klaatu’s robot servant Gort, or it will be destroyed.

War of the Worlds (1953)

Earth is under attack in this updating of H.G. Wells’s science fiction tale to the Cold War era as invaders from another world target a small California town with autonomous probes and laser disintegration rays.

Earth vs. The Flying Saucers (1956)

Scientist Russell Marvin is on-hand when an alien spacecraft lands on Earth. The aliens at first insist that they have come in peace, but Marvin suspects otherwise. Sure enough, the visitors eventually declare their intention to take over the Earth within the next 60 days, adding that the military’s weapons are useless against them. The two-month window gives Marvin and his cohorts plenty of time to build up a superweapon, and thus stave off the seven-saucer invasion force.

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956)

Emotionless aliens from outer space are using large seed pods to duplicate human bodies and take them over.

E.T.: The Extraterrestrial (1982)

An alien spacecraft on a scientific mission mistakenly left behind an aging botanist who isn’t sure how to get home. Eventually, young Elliott puts his fears aside and makes contact with the “little squashy guy,” perhaps the least threatening alien invader ever to hit a movie screen. As Elliott tries to keep the alien under wraps and help him figure out a way to get home, he discovers that the creature can communicate with him telepathically. Soon they begin to learn from each other, and Elliott becomes braver and less threatened by life. E.T. rigs up a communication device from junk he finds around the house, but no one knows if he’ll be rescued before a group of government scientists gets hold of him.

Independence Day (1996)

A series of massive spaceships approach Earth, which many greet with open arms, looking forward to the first contact with alien life. Unfortunately, these extraterrestrials have not come in peace, and they unleash powerful weapons that destroy most of the world’s major cities. Thrown into chaos, the survivors struggle to band together and put up a last-ditch resistance in order to save the human race.