Native America Prior to 1492

Native America

Most of the history that we acquire comes not from history textbooks or classroom lectures, but from images that we receive from movies, television, childhood stories, and folklore. Together, these images exert a powerful influence upon the way we think about the past. Some of these images are true, others are false. But much of what we think we know about the past consists of unexamined mythic images.

No aspect of our past has been more thoroughly shaped by popular mythology than the history of Native Americans. Quite unconsciously, Americans have picked up a complex set of mythic images. For example, many assume that pre-Columbian North America was a sparsely populated virgin-land. In fact, the area north of Mexico probably had seven to twelve million inhabitants. Also, when many Americans think of early Indians, they conceive of hunters on horseback. This image is misleading in two important respects: first, many Native Americans were farmers; second, horses had been extinct in the New World for 10,000 years before Europeans arrived.

One of history’s most important tasks is to identify myths and misconceptions and correct them. Nowhere is this more important than in the study of the Indian peoples of North America. Until remarkably recently, the history of Native Americans largely reflected the perspective, perceptions, and prejudices of European Americans. Even today, however, many of the distortions of an earlier Eurocentric history persist. Many textbooks still begin their treatment of American history with the European “discovery” of the New World—largely ignoring the first Americans, who crossed into the New World from Asia and established rich and diverse cultures in America centuries before Columbus’s arrival. Although few textbooks today use the word “primitive” to describe pre-contact Native Americans, many still convey the impression that North American Indians consisted simply of small migratory bands that subsisted through hunting, fishing, and gathering wild plants. As we shall see, this view is incorrect. In fact, Native American societies were rich, diverse, and sophisticated.

The most dangerous misconception about Native American history, however, is the easiest to slip into. It is to think of Native Americans as a vanishing people, who were fated for extinction and were the passive victims of an acquisitive, land-hungry white population. The view of Native Americans as passive victims is a gross distortion of historical reality. Far from being passive, Native Americans were active agents who responded to threats to their culture through physical resistance and cultural adaptation. And far from disappearing, Native Americans today have a growing population that retains rich cultural traditions.

Throughout their history, Native Americans have been dynamic agents of change. Food discovered and domesticated by Native Americans would transform the diet of Europe, Africa, and Asia. Native Americans also made many crucial—though often neglected—contributions to modern medicine, art, architecture, and ecology.

During the thousands of years preceding European contact, the Native American people developed inventive and creative cultures. They cultivated plants for food, dyes, medicines, and textiles; domesticated animals; established extensive patterns of trade; built cities; produced monumental architecture; developed intricate systems of religious beliefs; and constructed a wide variety of systems of social and political organization ranging from kin-based bands and tribes to city-states and confederations. Native Americans not only adapted to diverse and demanding environments, they also reshaped the natural environments to meet their needs. And after the arrival of Europeans in the New World, Native Americans struggled intently to preserve the essentials of their diverse cultures while adapting to radically changing conditions.

For more than half a century, the history of Native Americans largely took the form of tragedy. Indian history, from this viewpoint, was the story of declining population, lost homelands, cultural dislocation and persistent poverty and inequality. There is, however, another side to Native American history, a much more positive story that is missing from accounts that treat Indian history merely as an on-going tragedy. It is a story of cultural persistence and survival. The key themes of Native American history are continuity, resistance, resilience, and adaptability in the face of extraordinary challenges and dislocations.

Hidden History

Origins

In the spring of 1926, an African-American cowboy named George McJunkin made a discovery that profoundly altered our understanding of the first Americans in North America. While hunting for lost cattle along the edge of a gully near Folsom, New Mexico, he spotted some bleached bones. Those bones, it turned out, were the ribs of a species of bison that had been extinct for 10,000 years. Mixed in with the bones were human-made stone spearheads. The spearheads offered the first unambiguous proof that ancestors of today’s Indians lived in the New World thousands of years earlier than most early twentieth-century authorities believed—before the end of the last ice age.

Although the first Europeans to arrive in the Americas in the late fifteenth century called it the “New World,” it was a land that had been inhabited for more than 20,000 years. An enormous diversity of societies flourished, each with its own distinctive language, cultural patterns, and history. No written records record these histories. To reconstruct this story, it is necessary to turn to fragile archaeological artifacts that record past human behavior. From snippets of baskets, fragments of pottery, food remains, discarded tools, and oral traditions, anthropologists, archaeologists, and historians have pieced together information about these peoples’ social organization, technology, and diet, including how these have changed over time. This is a remarkable story, which underscores the ability of the First Americans to adapt to—and reshape—extraordinarily diverse environments, create their own rich and sophisticated cultures independent of outside influences, and establish elaborate trading networks and sophisticated religious systems.

When and how the ancestors of today’s Indians arrived in the New World remains one of the most controversial issues in archaeology. Many sixteenth-century Europeans believed that the Indians were descendants of the Biblical “Lost Tribes of Israel” or the mythical lost continent of Atlantis. In 1590, a Spanish Jesuit missionary, Jose de Acosta, came closer to the truth when he suggested that small groups of “hunters driven from their homelands by starvation or some other hardships” had traveled to America from Asia.

Most scholars believe that America’s first pioneers crossed into North America in the general area of the Bering Strait, which now separates Siberia and Alaska. Although the dates when the ancestors of today’s Native Americans migrated remain disputed, existing evidence suggests that the first migrants arrived between 25,000 and 70,000 years ago. The earth’s climate at that time was very different from today’s. The earliest Americans entered the New World during one of the earth’s periodic ice ages, when vast amounts of water froze into glaciers.

As a result, the depth of the oceans dropped, exposing a “land bridge” between Siberia and Alaska. Twice, such a land bridge appeared, between 28,000 and about 26,000 years ago, and between 20,000 and 10,000 to 12,000 years ago. In fact, the term “land bridge” is a misnomer; a vast expanse of marsh-filled land, a thousand miles wide, stretched between Siberia and Alaska. This land mass, now known as Beringia, allowed hunters from northeastern Asia to follow the migratory paths of animals that were their source of food into the more southernly parts of Alaska.

Supporting the notion that the first Americans came from Northeast Asia is the evidence of physical anthropology. Native Americans and northeast Asian people share certain common physical traits: straight black hair; dark brown eyes; wide cheekbones; and “shovel incisors” (concave inner surfaces of the upper front teeth).

Physical and linguistic evidence suggests that the migration into the Americas did not take place all at once. Many scholars believe that it took place in three distinct waves, with the Inuit (Eskimos) and the natives of the Aleutian Islands arriving more recently than the people who would inhabit the Pacific Northwest coast or other portions of North and South America.

The original settlers of North America were a remarkably adaptable people, capable of surviving in subfreezing temperatures in the tundra. In a climate much harsher than today’s, they were able to build fires, to construct heavily insulated housing, and to make warm clothes out of hides and furs.

Despite a lack of wheeled vehicles and riding animals, the first Americans spread quickly across North and South America. This momentous movement of people was propelled by population pressure, since hunters and gatherers require a great deal of territory to support themselves. A single family of hunter-gathers would hunt and forage more than six miles from their encampment, which equals a total area of 122 square miles.

Archaeological findings suggest that these people moved along three routes: eastward, across Canada’s northern coast; southward, along the Pacific Coast, as well as across the eastern Rocky Mountains, with some groups peeling off toward the eastern seaboard, the Ohio Valley and the Mississippi Valley.

Historical Facts & Fiction

Prehistoric Patterns of Change

Near Kit Carson, Colorado, archaeologists made an astonishing discovery. They found stone spearheads alongside the bones of extinct long-horned bison—evidence of a huge bison hunt around 8200 B.C. During this hunt, Native Americans drove some 200 bison into a gully before killing the animals. To butcher and carry away the 60,000 pounds of meat must have required at least 150 Indians working closely together.

At Bat Cave in southwestern New Mexico, archaeologists made another important find. There they found evidence that around 3000 B.C., Indians had learned to domesticate corn, the first grown north of Mexico. It was a primitive form of corn, with stalks barely an inch long and no husk to protect the kernels. Still, it was a sign that these people were no longer wholly dependent on wild food sources; they were now able to supplement their diet by cultivating crops.

It is from discoveries like these that archaeologists reconstruct the prehistory of North America’s Indians. They have found that the earliest New World pioneers hunted large mammals—bison, caribou, oxen and mammoths—with stone-tipped spears and spear and dart throwers, known as atlatls. Between 6,000 and 12,000 years ago, however, many large animal species became extinct. Archaeologists do not agree why these animals died out. Some argue that it was the result of overkilling; others attribute it to climatic changes: rising temperatures, the drying up of many lakes, and the loss of many early forms of vegetation. As a result, the ancestors of today’s Indians had to dramatically alter their way of life.

As the larger mammals died out and the Indian population grew, many Indian peoples turned to foraging, gathering plant foods, fishing, and hunting smaller animals. To hunt small game, these people developed new kinds of weapons, including spears with barbed points, the bow and arrow, and nets and hooks for fishing. This era, known as the Archaic period, offers many examples of these peoples’ increasing technological sophistication, evident in the proliferation of such objects as awls, axes, boats, cloth, darts, millstones, and woven baskets.

Following the Archaic period came the Formative period, when some foragers began to domesticate wild seeds. By 3000 B.C., some groups of Southwestern Indians had already begun to grow corn. The rise of agriculture allowed these people to form permanent settlements.

The Cultures of Pre-Columbian America North of Mexico

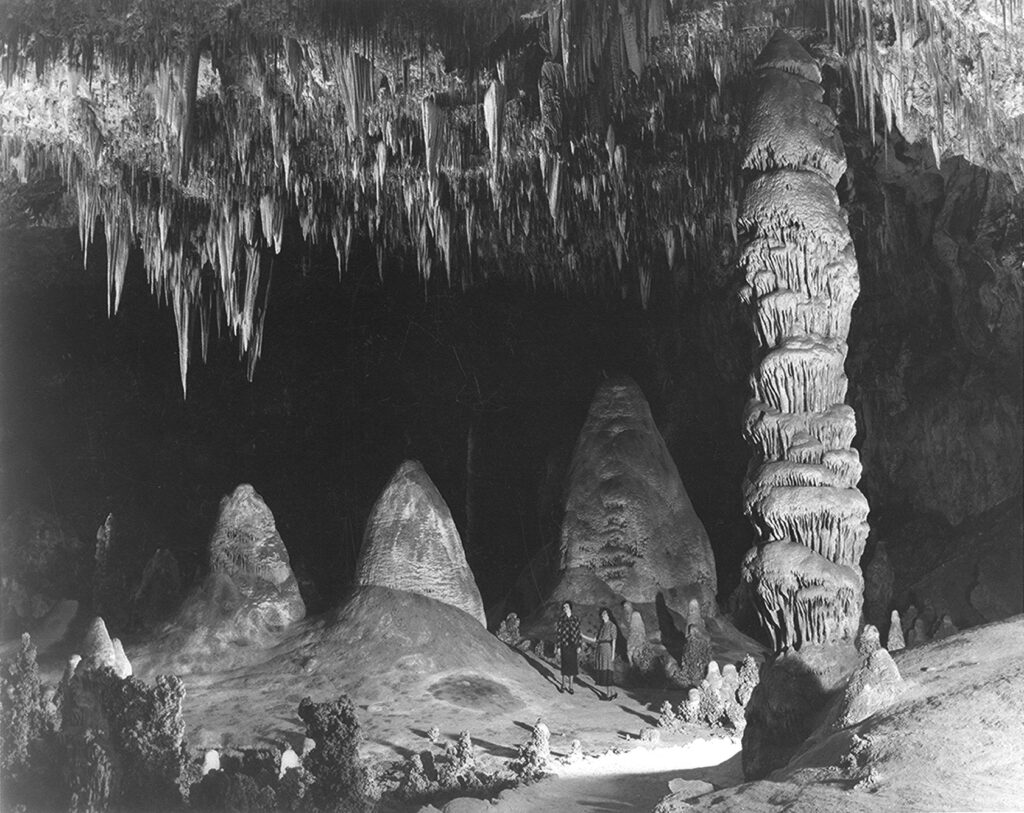

Across from present-day St. Louis stands an earthen mound one hundred feet high and covering fifteen acres, bigger at its base than the Great Pyramid of Egypt. This mysterious mound is one of thousands that early Native Americans built in the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys, the Great Lakes region, and along the Gulf Coast.

Before the 1890s, many authorities refused to believe that Indians could have created these mounds since they lacked horses, oxen, or wheeled vehicles; they thought that the Vikings or the Lost Tribes of Israel or some long vanished civilization constructed them. We now know that they were built by Native Americans to serve as burial places and as platforms for temples and the residences of chiefs and priests.

Many of these New World monuments are truly immense. One Ohio mound resembles a huge snake and measures a quarter of a mile long. A Georgia mound has a figure of an eagle across its top. The mounds provide clues to the rich and diverse cultures that Native Americans created during the more than 20,000 years before Europeans reached the New World.

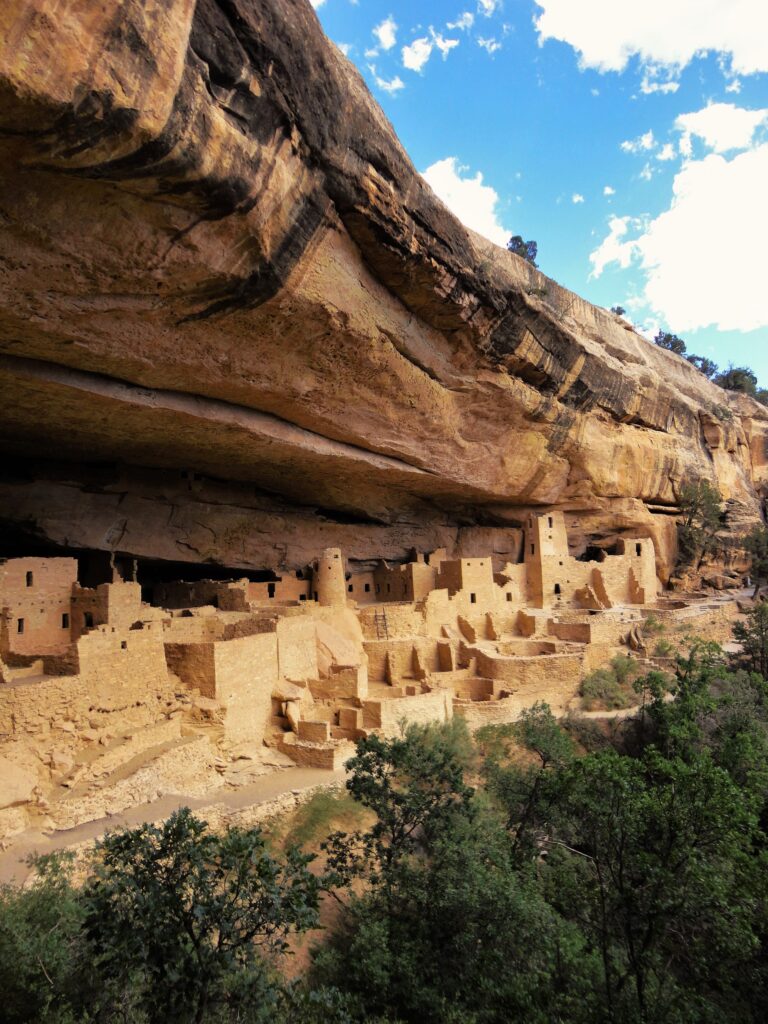

Earthen mounds are not the only magnificent monuments that the Indians produced. On the face of a sandstone cliff in present-day Mesa Verde, Colorado, is a spectacular stone and adobe structure that once housed over four hundred people in two hundred rooms. Located a hundred feet above a nearby plateau, the structure is accessible only by climbing wooden ladders and using toe holds cut in the sandstone. In southern Colorado and Utah, northwestern New Mexico, and northern Arizona, hundreds of similar communal dwellings are located in shallow caves or under cliff overhangs.

The first Europeans to arrive in the Americas in the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries were an arrogant, ethnocentric people who drew a sharp contrast between their societies’ technological accomplishments and those of the New World Indians. And while it is true that the Indian peoples had no steel or iron tools, wheeled vehicles, large sailing vessels, keystone arches or domes, digital numbers, coined money, alphabet system of writing, or gunpowder, this does at all mean that they did not create thriving and inventive societies. For one thing, the Indians were the first people to cultivate some of the world’s most important agricultural crops: chocolate, corn, long-staple cotton, peanuts, pineapples, potatoes, rubber, quinine, tobacco, and vanilla. In addition, the New World Indians built cities as big as any in Europe, established forms of government as varied as Europe’s and created some of the world’s greatest art and architecture, including temples, pyramids, statues, and canals.

While many Americans are aware of the impressive cultures that thrived in Mexico, Peru, and Guatemala before Columbus’s arrival—the Toltec, the Maya, the Aztec and the Inca—far fewer are familiar with the magnificent ancient cultures to be found north of Mexico. In fact, from the Alaska tundra to the dense evergreen forests of the Pacific Northwest, from the arid deserts of the Southwest to the rich river valleys of the Southeast and the eastern woodlands, prehistoric Native Americans established complex cultures, ingeniously adapted to diverse conditions.

The first Americans had to adapt their ways of life to vastly different environments. Before 2000 B.C., the ancestors of the Inuit and the Aleuts arrived on the coast and frozen tundra of western Alaska, where they adapted ingeniously to arctic conditions. Since few plants grew in the harsh arctic climate, the Inuit relied on hunting and fishing. They drew much of their food from the sea, hunting seals, whales and other marine mammals. The game they hunted not only provided food, but also protection from the extreme cold. The Inuit wore layers of caribou-skinned clothing and constructed heavily insulated pit houses, dug into the ground and covered with furs and animal skins. The Inuit built sleds for transportation and spread out across the coast. These people were organized in a large number of small bands, which shared certain common cultural patterns while remaining largely autonomous.

It was in the arid Southwest that some of the earliest farming societies developed. The predecessors of the Pueblo and Navajo Indians were able to flourish in a desert environment by developing complex irrigation systems for farming and by developing structures suitable for vast temperature changes.

Along the Northwest Pacific Coast—an area of dense forests, teeming with caribou, deer, elk, and moose, and rivers rich with sea life—the ancestors of the Haidas, Kwakiutls, and Tlingits developed a distinctive culture oriented toward the water. The mild climate and the abundant marine life—salmon, sturgeon, halibut, herring, shellfish, and sea mammals—meant that these peoples could produce food with very little work. Such abundance freed these people to create some of the world’s most impressive art forms as well as an elaborate ceremonial life. The people of the Northwest Pacific Coast constructed large, gabled-roof plank houses; carved family and clan emblems on totem poles; made elaborately carved wooden masks, grave markers and utensils; and constructed great sea-going canoes, some more than sixty feet long. The region’s abundant resources also produced a highly stratified society, where a few wealthy families controlled each village. Individuals announced their high social status at a feast called a potlatch. During this ritual, which could last for several days, a host demonstrated his wealth by distributing food and gifts to his guests.

Shifts in climate appear to have played an important role in encouraging the development of agriculture in the Southwest. Between three and five thousand years ago, the amount of rainfall in this region increased, encouraging many people to migrate to the area, including some from Mexico already familiar with raising corn, squash, and beans. These people raised crops casually, supplementing a diet that depended largely on hunting and foraging.

Around 3,000 years ago, however, the climate grew drier, killing off many of the region’s wild game and vegetation. A people known as the Mogollon, who lived in permanent villages along the rivers of eastern Arizona and western New Mexico, responded to this change by devoting increased energy to farming, raising beans, squash, and corn. The versatility of the Mogollon is also apparent in the housing they constructed. To cope with the desert extremes of heat and cold, they built pit houses, structures burrowed two or three feet into the ground and covered with woven reeds and plaster made out of mud.

In central Arizona, the Hohokam, a group that had migrated from Mexico, constructed elaborate irrigation systems in order to transform the desert into farm land. They dug wells, built ponds and dams to collect rainwater and created hundreds of miles of canals and ditches to channel water to their crops. The Hohokam combined farming with trade, which involved luxury goods such as precious stones, ornamental sea shells, and copper bells.

The Anasazi also used dams and irrigation canals to water their crops. Between 1000 and 1300 A.D., the Anasazi culture spread across much of northern Arizona, northern New Mexico, southern Colorado, and southern Utah, establishing more than twenty-five thousand separate communities spread over sixty thousand square miles connected by a remarkable system of roads. The Anasazi are best known today for their magnificent cliff dwellings, multi-roomed dwellings built atop mesas or along steep cliffs. By 1300, however, the Anasazi abandoned these cliff dwellings and moved to the south and east, apparently in response to incursions from hostile Indians and a severe drought that threatened their food supply. The Anasazi are the ancestors of the modern-day Pueblo Indians.

The arrival of a new people into the Southwest, the Athabascans, created an important challenge to the Anasazi way of life. About A.D. 1000, bands of Athabascans, the ancestors of the Navajos and the Apaches, began to migrate to the Southwest from what is now Alaska and Canada. Formidable hunters and raiders, the Athabascans possessed the bow and arrow, and during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, raided Anasazi farming communities and by 1500 had taken over the western desert. They lived in settlements consisting of “forked stick” homes, made by piling logs against three poles joined together at their tops, then covering the outside with mud. Later they fashioned hogans, earthen domes with log frames.

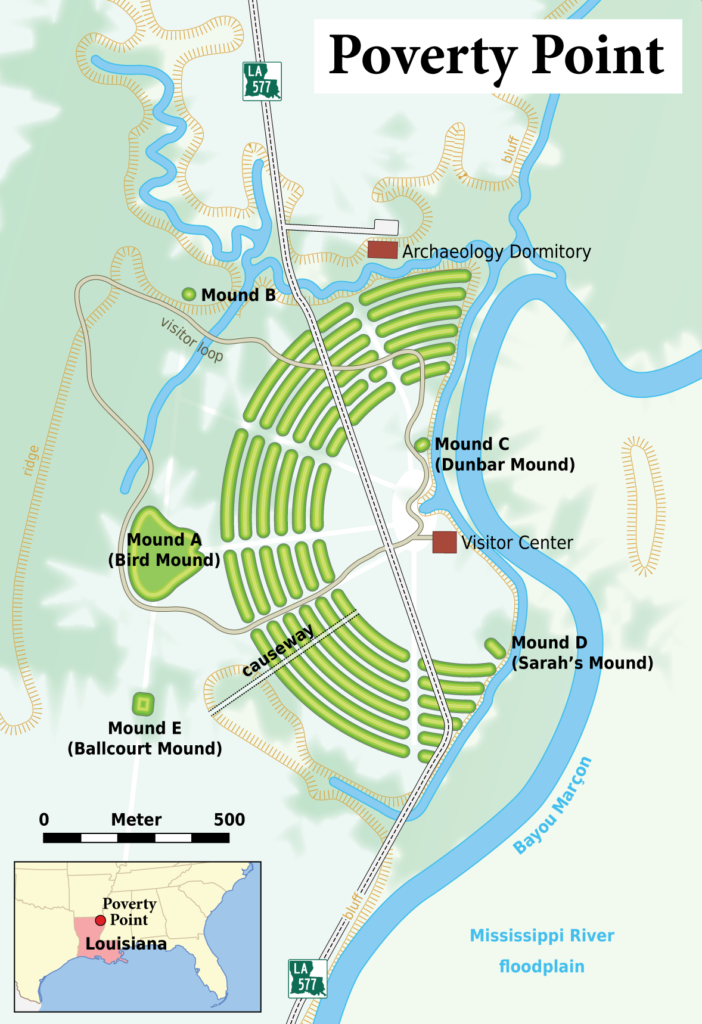

Around 700 B.C., other groups of people, known as the Adena, began to build large mounds and earthworks in southern Ohio. The Adena lived in small villages and supported themselves by hunting, fishing, gathering wild plants, modest farming, and some trading. The Adena built mounds as burial places. The bodies of village leaders and other high ranking people were placed in log tombs before being covered with earth. Along the lakes and rivers of the Midwest and the Southeast, prehistoric Americans established complex communities based on flourishing trade and agriculture. One of the earliest farming and trading towns arose around 1400 B.C. on the banks of the lower Mississippi River near present-day Vicksburg, Mississippi. Known as Poverty Point, the town showed many signs of Mexican influence, including a cone-shaped burial mound and two large bird-shaped mounds, and other huge earthworks. Networks of trade apparently connected Poverty Point with settlements along the Mississippi, Ohio, Missouri, and Arkansas rivers. Thus, thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans, Native Americans were already engaged in extensive trade of flint, copper, and other goods.

The Hopewell created stratified societies and buried their leaders in earthen mounds filled with art works made of materials imported from areas more than a thousand miles away. The Hopewell built many more mounds than the Adena. A colder climate appears to have contributed to the decline of the Hopewell beginning around 450 A.D. From about 100 B.C., a new mound-building culture flourished in the midwest, known as the Hopewell. These people developed thousands of villages extending across what is now Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin, Iowa, and Missouri. The Hopewell supported themselves by hunting, fishing and gathering, and also cultivated a variety of crops, including corn. The Hopewell developed an extensive trading network, obtaining shells and shark teeth from Florida, pipestone from Minnesota, volcanic glass from Wyoming, and silver from Ontario.

After 750 A.D., another mound-building culture, known as the Mississippians, emerged in the Mississippi valley and the Gulf Coast. By cultivating an improved variety of corn and using flint hoes instead of digging sticks, these people greatly increased agricultural productivity, permitting them to build some of the largest cities in prehistoric North America. The largest that we know about was Cahokia, across from present-day St. Louis, which probably had a population of 20,000. To protect the population from raids from neighboring peoples, many of these cities were protected by stockades. Like the Indians of Mexico, the Mississippians built flat-topped mounds in the center of their cities, where chiefs lived and the bones of deceased chiefs were kept.

The largest of the Mississippian settlements may have become city-states, exercising control over surrounding farm country. Within their towns, the Mississippians created a complex, stratified society, with a distinct leadership class, specialized artisans, an extensive system of trade and priests. The Mississippians practiced a religion known as the southern ceremonial complex. Somewhat similar to Mexican Indian religions, the “southern cult,” as it is known, provided a set of symbols and motifs of rank and status that recur in Mississippian art, notably a flying human figure with wing-like tattoos around the eyes.

The Mississippian cultures grew until the 1500s, when diseases introduced by European explorers resulted in a sharp decline in population. However, one group of Mississippians, the Natchez, survived into the 1700s, long enough to be described by Europeans.

The Eve of Contact

When Columbus arrived in the Caribbean in 1492, the New World was far from an empty wilderness. It was home to as many people as lived in Europe, perhaps 60 or 70 million. Between seven and twelve million lived in what are now the United States and Canada. Not a single homogeneous population, the people north of Mexico lived in more than 350 distinct groups, which spoke more than 250 languages and had their own political structure, kinship systems and economies. These divisions would have fateful consequences for the future, permitting the European colonizers to adopt divide-and-conquer policies that played one group off against others.

Diversity—economic, political and cultural—was a hallmark of Native America on the eve of contact. There were groups with no formal state organization and no permanent social classes; there were small-scale states that did have a hierarchical social structure; and there were also “imperial states” with a more complex, hierarchical social structure and power extending over a variety of conquered peoples.

Modes of subsistence also varied widely. There were peoples who did not farm, but engaged in foraging; and there were those who engaged in agriculture with varying levels of intensity. Some peoples lived in large, compact permanent settlements. Others lived in scattered villages; still others migrated frequently. Some peoples had slaves, many others did not.

In each geographical and cultural area, there were deeply rooted historic conflicts and vulnerabilities that European colonizers would exploit. In the Southwest, many conflicts arose over control of the arid region’s scarce resources, as groups like Yaquis and the Pimas struggled over access to water and fertile land. In the northern portion of the Southwest, village dwellers, such as the Hopi and Zuni, coexisted uneasily with migratory hunters and raiders like the Apache. In the southern Southwest, patterns of land use would make the inhabitants especially vulnerable to Spanish encroachment. The dominant groups, the Pimas and the Papagos lived in isolated communities, known as rancherias, spread across a thousand miles along streams and other sources of irrigation. The Spaniards would adopt a policy that sought to “reduce” the dispersed Indian population into supervised towns.

In the Southeast—where the Creeks, the Choctaws, the Cherokees, the Seminoles and other peoples lived—extensive European colonization was delayed until the seventeenth century because the area lacked precious minerals. Here, Mississippian cultural patterns persisted: towns, with several hundred to a few thousand residents; farming, fishing and hunting; varying degrees of social stratification; and a pronounced tendency toward matrilineality (tracing descent through the mother’s family) and matrilocality (newly married couples residing with and working for the mother’s family). Forms of political organization ranged from autonomous towns to sets of villages that paid tribute to a dominant town. A history of intertribal warfare in the Southeast led many tribes to band together for protection in confederations.

Stretching from the Atlantic coast west to the Great Lakes and southward from Maine to North Carolina lay the eastern woodlands. The eastern woodland’s major groups were the Algonquians, the Iroquois and the Muskogeans.

The Algonquians lived in small bands of from one to three hundred members, combining hunting, fishing, and gathering with some agriculture. A semi-nomadic people who might move several times a year, the Algonquians would plant crops, then break into small bands to hunt caribou and deer and return to their fields at harvest time. These people lived in wigwams, dome-shaped structures containing one or more families. A wigwam, made of bent saplings covered with birch bark, typically housed a husband and wife, their children, and their married sons and their wives and children.

During the 1600s, the Algonquians and their allies the Hurons fought a bitter war against the Iroquois. Around 1640, the Algonquians were defeated and driven from their territory. This war and epidemics of measles and smallpox reduced the Algonquian population sharply.

The Iroquois were several related groups of people who still live in what is now central New York. Scholars disagree about whether the Iroquois had long occupied this area or whether they migrated from the Southeast around 1300. What does seem clear is that beginning in the fourteenth century, bitter feuds broke out among the Iroquois, which grew particularly intense during the sixteenth century. According to Iroquois oral tradition, two reformers, Dekanawidah, a Huron religious leader, and his disciple Hiawatha, a Mohawk chief, responded to mounting conflict by proposing a political alliance of the Iroquois tribes. During the sixteenth century, five Iroquois tribes—the Cayugas, the Mohawks, the Oneidas, the Onondagas and the Senecas—joined together to form a confederation known as the Iroquois league. A sixth tribe, the Tuscarora, joined the league in the eighteenth century.

Governing the league was a council, consisting of the chiefs of each tribe and 50 specially chosen leaders called sachems. Some scholars argue that the Iroquois League, which combined a central authority with tribal autonomy, provided a model for the federal system of government later adopted by the United States.

Women played a very important role in Iroquois society—a fact that shocked Europeans. Women headed the longhouses that were the basic units of social and economic organization among the Iroquois and were also the leaders of clans, which were comprised of several longhouses. Although women did not sit on the league councils that made decisions involving war and diplomacy, the women who headed the clans did have the power to appoint or remove the men who served on these councils.