How the World Came to be Divided

How the World Came to be Divided

Today, hundreds of thousands of people across the Middle East, North Africa, and Central America are fleeing war, poverty, and persecution. They risk their lives to reach Europe or the United States. Why? Because the world is divided between areas that are prosperous and orderly and those that are poor and disorderly. How the world came to be divided is one of the topics that this course will explore.

In 1492, it was not obvious that Europe would come to dominate the world economy. At that time, Ming China, the Ottoman Empire, and the Mogul Empire in South Asia seemed far wealthier, more populous, and more powerful.

Take the example of China. The magnetic compass was a Chinese invention. China produced more iron than Britain did seven centuries later. It had a well-developed canal system, paper money to facilitate commerce, printing by movable type as early as the 11th century, and had invented gunpowder. In 1420, the Ming navy possessed 1,350 combat vessels. Its population in 1500 was between 100 and 130 million, while Europe’s was just 50 to 55 million.

Or take the Muslim world, which was clearly superior to Europe in mathematics, cartography, and medicine. Its mills and ability to cast guns far exceeded Europe’s capabilities. Constantinople, the capital of the Ottoman Empire, was bigger than any European city, possessing over 500,000 inhabitants in 1600.

In contrast, Europe’s soil was not particularly fertile, nor was its population especially large. Politically, Europe consisted of a hodgepodge of petty kingdoms, principalities and city states. Even in those countries with increasingly powerful monarchies—notably Spain, France, and England—there were severe internal tensions. Indeed, in the 1540s and early 1650s, England would experience prolonged civil wars.

By such measures as life expectancy and child mortality, Europe was at roughly the same stage of development as most other parts of the world. Life expectancy at birth was roughly 40 in Africa, the Americas, Asia and Europe. Child mortality killed one child in three or four in all parts of the world.

Nor was Europe any more advanced technologically or mighty militarily compared to the great civilizations of the Middle East, the Near East, or south and east Asia. Indeed, a considerable amount of its technology and science was borrowed from Muslim societies which, in turn, had drawn upon civilizations in China and India. It was not until the late nineteenth century that European military power was sufficient to create colonies across Africa and parts of Asia.

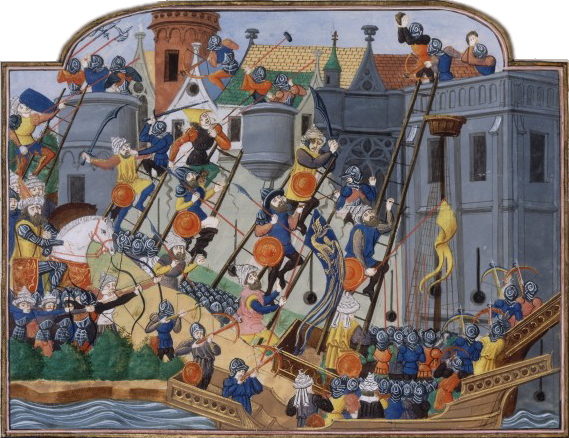

Indeed, in the fifteenth century, Europe felt besieged. In 1453, Constantinople, the capital of eastern Christianity, fell to the Ottoman Empire. By the 1520s, the Ottomans had captured Greece, Bosnia, Albania and the rest of the Balkans and were expanding westward toward Budapest in Hungary and Vienna in what is now Austria.

Thinking Comparatively

But by the Beginning of the Sixteenth Century, European Power Was on the Rise. How Did This Happen?

Part of the answer lies in policies adopted by the great powers of the age. In China in 1436, an imperial edict forbade the construction of seagoing ships; it also issued an order prohibited the existence of ships with more than two masts. Why did China’s government take steps that would inhibit growth?

In part, it was a response to a perceived military threat from Mongols along China’s northern frontier. But it also reflected the sheer conservatism of the bureaucracy, which was highly suspicious of traders. China’s leaders disliked commerce and confiscated merchants’ property and banned their businesses. Printing was restricted to scholarly works and the use of paper currency was discontinued.

What about the Muslim World?

During the early 1500s, the Muslim states were rapidly expanding. The Ottoman Empire pushed westward into Europe from Crimea to the Aegean, including what is now Bulgaria, Serbia, and Hungary, and launched raids on Italy and Spain.

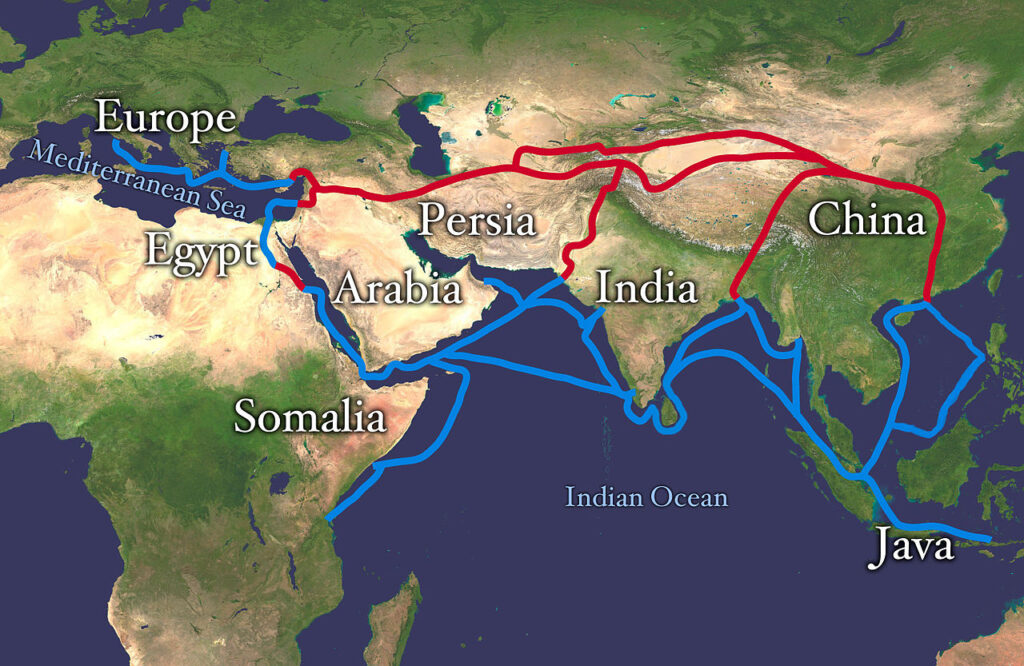

At the same time, a Muslim dynasty in Persia was expanding as was the Muslim Mogul Empire which conquered India. Other Muslim political entities controlled the Silk Road, the network of trade across Asia, dominated trade across West Africa and triumphed in Java (or what is now Indonesia). By the mid-sixteenth century, the Ottoman Empire exceeded the Roman Empire in size. At a time when Spain had just five million inhabitants and England just 2.5 million, the Ottoman Empire included 14 million subjects.

But the Muslim world also faced challenges from within. There was a sharp religious divide between Shi’ites and Sunnis. As in China, there was a great deal of hostility toward commerce, with merchants subject to unpredictable taxes, duties, and seizures of property. Meanwhile, peasants’ land and stock were preyed upon by soldiers. Restrictions were imposed upon exports and the printing press. The Ottoman Empire failed to build light cast iron guns or to construct ocean-going vessels.

Why, Then, Did Europe Become the Leader in Commerce, Economic Development, and Technological Innovation?

Part of the answer lies in Europe’s political fragmentation. For a time, it appeared that Spain, under Charles I, would dominate continental Europe and beyond.

Charles I’s empire stretched from the Americas to the East Indies, and from the Low Countries to territories now in France, Germany, and Italy in Europe. It also encompassed the Portuguese Empire from 1580 to 1640 and small enclaves in North Africa. Altogether, it included 13 percent of the world’s land area and about 12 percent of the world’s population. But its dominance proved fleeting.

Rivalries between European states stimulated economic growth and military advances. When one power, such as Portugal or Spain, declined, another power—England, France, or Holland—was well-positioned to take its place. In contrast, Ming China, the Ottoman Empire, and the Mogul Empire were overly centralized, insisting not only on a single religion, but on constraints on commerce and even on military innovation.

The absence of strong central authority meant that commerce could flourish in Europe without the kinds of restrictions found in China or the Ottoman Empire. Europe’s towns, too, were freer from centralized control. Merchants could trade largely free from the constraints found elsewhere.

The climate and landscape made a difference, too. Europe’s climate varied widely and its landscape was sharply differentiated, with mountains and forests separating parts of the continent, making it difficult for any single nation to achieve dominance. Europe’s regions specialized in very different products; not luxury goods, but rather commodities traded across the continent, including timber, grain, wine, wool and herring.

Europe’s many navigable rivers and ready access to the Mediterranean and the Atlantic encouraged shipbuilding and maritime commerce, which led to the development of banking, credit, and insurance on an international scale. Rough waters encouraged shipwrights to build tough vessels capable of carrying large loads using wind power alone, rather than galley slaves. Sailing ships had longer range than galleys, which would allow Europe to control transoceanic trade routes.

A complex mixture of motives—personal gain, national glory, religious zeal, a sense of adventure—would fuel Europe’s drive toward global expansion. Acquisitiveness was encouraged. Traders not only sought gold, silver and spices, but also fish, sugar, indigo, tobacco, rice, furs and timber as well as plants they would encounter in the Americas like the potato and corn.

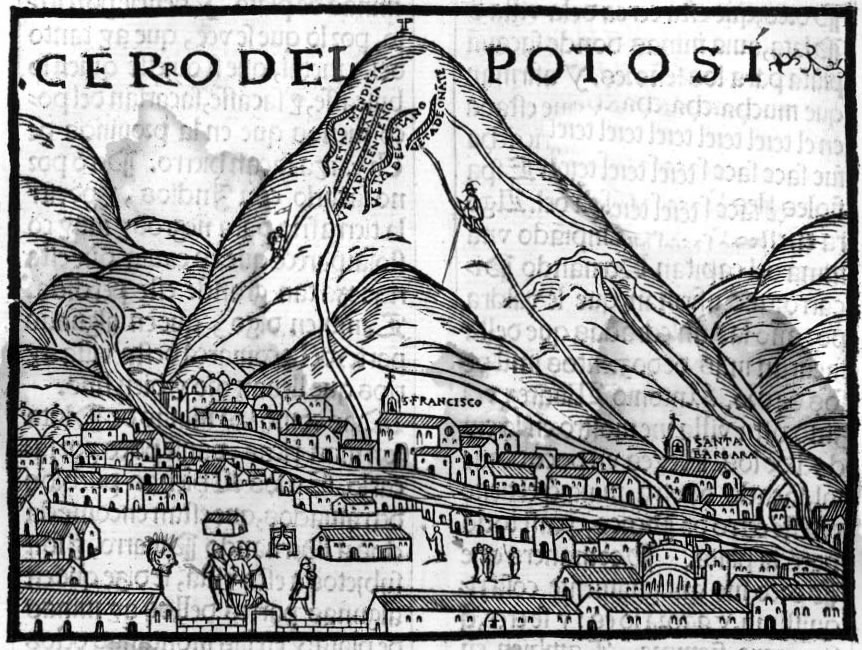

What would emerge beginning in 1492 was the dawn of an integrated world economy, which brought together furs, hides, wood, hemp, salt, and grain from Russia and the Baltics; gold and slaves from West and Central Africa; silver from Peru and Mexico; and spices and silk from the Far East.

By the 1560s, Dutch, English and French vessels had joined the Spanish and Portuguese in venturing across the Atlantic and into the Indian and Pacific oceans. Trade, in turn, led to improvements in mapmaking, the development of new instruments like the barometer and compass, and advances in botany, metallurgy and engineering, with news of each discovery disseminated by the printing press.