The World in 1492

Zheng He

Twenty-four miles southeast of Houston, a Saturn V moon rocket lies on the ground. Not a mock up, the rocket’s boosters and command module were meant to fly as Apollo 18. However, the mission was cancelled in 1970 for budgetary reasons.

In 1970, the federal government made a fateful decision: to abandon lunar exploration. The nation would now settle for more modest goals. The space shuttle would fly no higher than 330 miles above sea level. The moon is 238,900 miles from Earth.

This was not the first time in history people ventured forward only to step back.

Several decades before Columbus sailed to the New World, a Chinese admiral named Zheng He (pronounced Jung Huh) made even more ambitious voyages. Between 1405 and 1433, Zheng He led seven major expeditions, commanding the largest armada the world would see for the next five centuries.

Zheng He’s ascent to power was unlikely. A Muslim, he was taken as a prisoner by the Ming army and was castrated. He survived the ordeal, and became a servant in the household of a Ming prince, Zhu Di, whom he befriended. After the prince succeeded in overthrowing China’s emperor, he gave Zheng He command of an armada that would sail seven epic expeditions. He brought China’s “treasure ships” across the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean, from Taiwan to Indonesia, the coast of India, the ports of the Persian Gulf and along the African coast.

Zheng He’s fleet included 28,000 sailors on 300 ships, the longest of which were 400 feet and 160 feet wide. By comparison, Columbus in 1492 had 90 sailors on three ships; the biggest was 85 feet long. Zheng He’s armada included supply ships to carry horses and as many as 20 tankers to carry fresh water. His crew included interpreters for Arabic and other languages, astrologers to forecast the weather, astronomers to study the stars, pharmacologists to collect medicinal plants, ship-repair specialists, doctors and even two protocol officers to help organize official receptions.

Zheng He’s fleet reached Africa and could easily have continued around the Cape of Good Hope and established direct trade with Europe. But the Chinese regarded Europe as a backward region and had little interest in the wool, beads and, wine Europe had to trade. China preferred the goods that Africa traded—ivory, medicines, spices and exotic woods.

In Zheng He’s time, China and India together accounted for more than half of the world’s gross national product. Indeed, as recently as 1820, China accounted for 29 percent of the global economy and India another 16 percent.

But during the 1400s, China retreated into relative isolation. By 1500 the Chinese government had made it a capital offense to build a boat with more than two masts, and in 1525 the Government ordered the destruction of all oceangoing ships. In 1420, the Ming navy possessed 1,350 combat vessels, about five times as many as the U.S. Navy in 2015 when it had 272 such vessels.

The writer Nicholas D. Kristof has offered an explanation for China’s retreat into insularity. China’s leadership, Kristof observes, proved far less willing than Western Europeans to pursue wealth and economic growth. The Chinese elite “cared about many things—prestige, honor, culture, arts, education, ancestors, religion, filial piety—but making money came far down the list.” In contrast, the European merchants and traders ventured into Africa, Asia, and the Americas in pursuit of wealth and economic opportunity. They sought gold, silver, and spices, but also more mundane products, including fish and wood. “It was the hope of profits that drove its ships steadily farther down the African coast and eventually around the Horn to Asia. The profits of this trade could be vast: Magellan’s crew once sold a cargo of 26 tons of cloves for 10,000 times the cost.”

Another reason for fifteenth century China’s mounting isolation lay in “a suspicion of new ideas” and a commitment to traditionalism. According to Kristof, “Chinese elites regarded their country as the ‘Middle Kingdom’ and believed they had nothing to learn from barbarians abroad.” The fifteenth-century Portuguese were the opposite. Because of its coastline and fishing industry, Portugal always looked to the sea, yet rivalries with Spain and other countries shut it out of the Mediterranean trade. So the only way for Portugal to get at the wealth of the East was by conquering the oceans.

Yet another reason for China’s retreat from global exploration is that China was a single country while Europe consisted of many competing, large, wealth-seeking countries. When Chinese bureaucrats banned shipping, long-distance commerce ceased. But in Europe no single country was able to dominate the continent. Portugal and Spain would have to compete with Holland, France and England.

Timbuktu

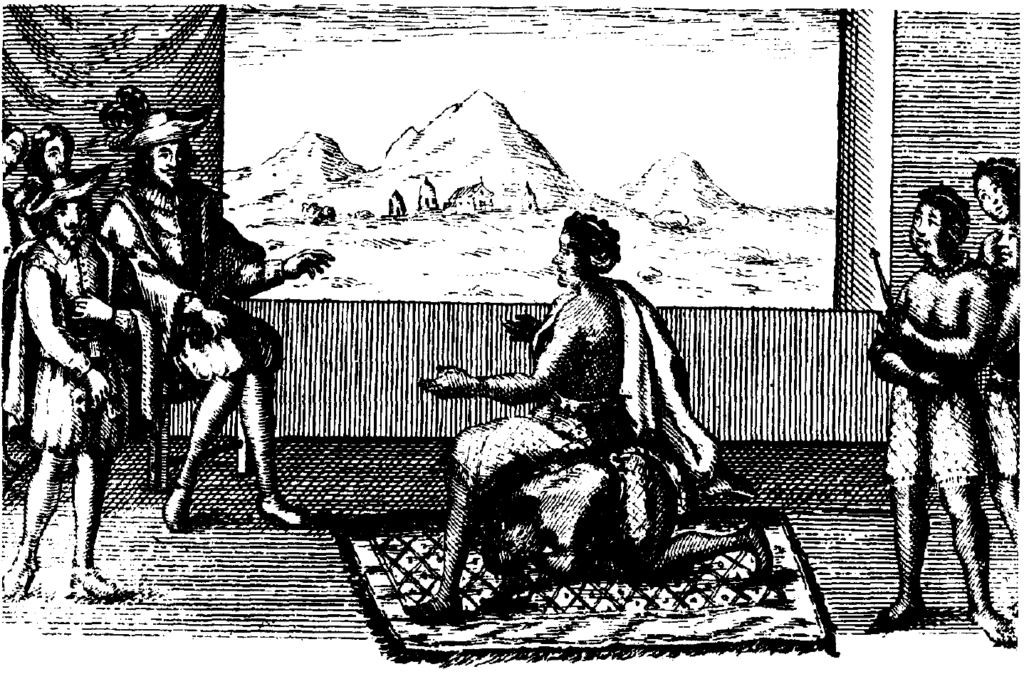

In the popular imagination, Timbuktu is the most remote and isolated place in the world. But 500 years ago, Timbuktu was the legendary city of gold. It was a transit point and a financial and trading center for trade across the Sahara. It was a place of mystery and faraway riches.

Timbuktu was founded in 1080 and within 300 years had become one of the era’s most important trading points. In addition to dominating the gold trade, Timbuktu was an influential Islamic intellectual center, a cosmopolitan, and multicultural city of commerce and learning with the second-largest imperial court in the world.

When much of Europe was struggling out of the Middle Ages, the emperor of Timbuktu built stunning mosques, and thousands of scholars from as far as Islamic India and Moorish Spain studied in the city.

Then, it was a city of perhaps 100,000 and so rich that even the slaves were decorated with gold. In 1324, a king of Mali, Mansa Musa, traveled with a caravan of a hundred camels bearing 300 pounds of gold each (equal to perhaps $135 million, today).

The legend of his wealth was recorded in maps, particularly the Catalan Atlas of 1375, which showed an African ruler enthroned like a European monarch with a crown on his head and a golden orb and scepter in his hand.

Until relatively recently, many scholars treated sub-Saharan Africa as if it were without history. As recently as 1963, a famous British historian, Hugh Trevor-Roper, said: “Perhaps in the future, there will be some African history to teach. But at present there is none. There is only the history of Europeans in Africa. The rest is darkness.”

Trever-Roper was wrong. Timbuktu was once a center of religion, culture, and learning, as well as a commercial crossroads on the trans-Saharan caravan route. Situated at the strategic point where the Sahara touches on the River Niger, it was the gateway for African goods bound for the merchants of the Mediterranean, the courts of Europe, and the larger Islamic world. It was involved in a thriving commerce in gold, salt, and slaves. When the Renaissance was barely stirring in Europe, wandering scholars were drawn to Timbuktu’s manuscripts all the way from North Africa, Arabia and even Persia.

In 1591, Moroccan soldiers invaded and looted Timbuktu, ending the city’s grandeur and taking thousands of inhabitants as slaves. By the time Timbuktu was discovered by Europeans, the palaces of its kings and other fine buildings had crumbled to dust.

Cahokia

While many Americans are aware of the impressive cultures that thrived in Mexico, Peru, and Guatemala before Columbus’s arrival—the Toltec, the Maya, the Aztec, and the Inca—far fewer are familiar with the magnificent ancient cultures to be found north of Mexico. In fact, from the Alaska tundra to the dense evergreen forests of the Pacific Northwest, from the arid deserts of the Southwest to the rich river valleys of the Southeast and the eastern woodlands, prehistoric Native Americans established complex cultures, ingeniously adapted to diverse conditions.

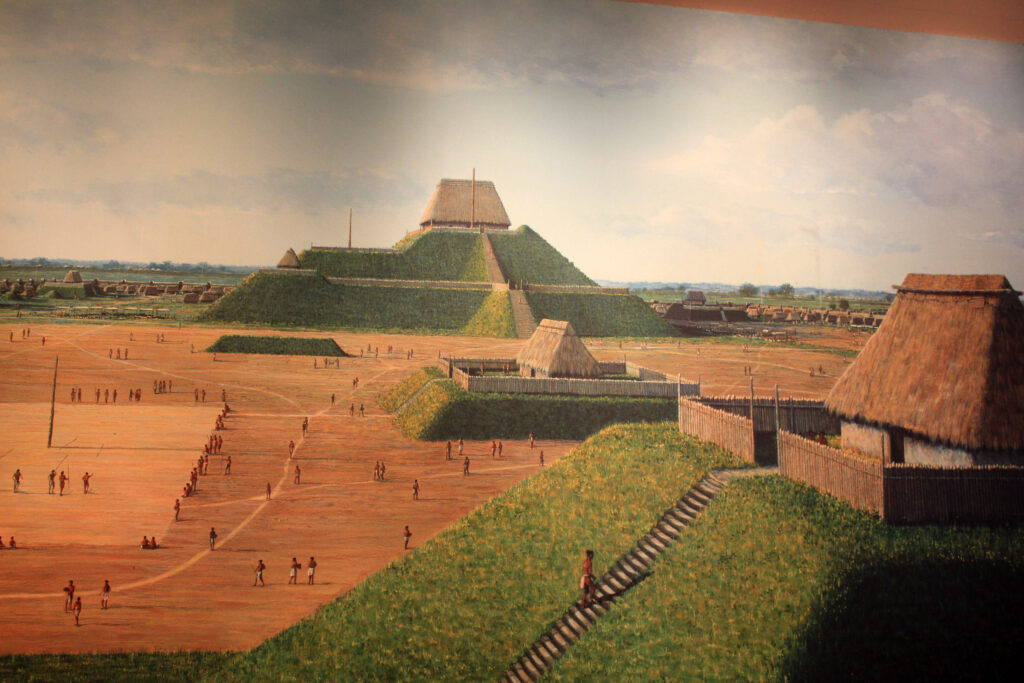

Many Americans visit Stonehenge in England. They are unaware their own country contains similar feats of ancient engineering. One site, located across the Mississippi River from St. Louis, contained 120 earthen pyramids and plazas. One earthen mound is larger than the Great Pyramid in Egypt. Its base covered 14 acres and it rose in four terraces to 100 feet

The oldest city in what is now the United States was not Jamestown, the first enduring English settlement founded in 1607, or St. Augustine, established in 1565. The title goes to Cahokia along the flood plains of the Mississippi River, near present-day St. Louis. Named for an unrelated tribe that settled there centuries later, Cahokia was first settled around 600 c.e. Apparently a center for religious observance, Cahokia’s population peaked between 10,000 to 20,000 around 1100 C.E., making it as large as the most sizable cities in the American colonies in the mid-eighteenth century.

As early as the year 1000 A.D., Cahokia had a clearly defined ceremonial zone, an administrative center, elite compounds, and a variety of residential centers. At a time when many European cities were little more than villages, the people living at Cahokia built a wooden barricade surrounding their most important buildings. Almost two miles long and enclosing more than 120 acres, the fence required felling 15,000 trees.

Cahokia, the largest settlement north of central Mexico, flourished for three centuries before it was abandoned. Cahokia’s merchants traded across much of North America, from the Gulf Coast northward to the Great Lakes, eastward to the Atlantic coast and westward to Oklahoma. Cahokia spread its culture across much of North America. Farmers grew squash, local grains, sunflowers, and corn.

At Cahokia’s core, within a log stockade ten to twelve feet tall, was the 200-acre Sacred Precinct where the ruling elite lived and were buried. On top of a massive earthen mound stood a pole-framed temple more than 100 feet long, where Cahokia’s rulers performed the political and religious rituals. Cahokia’s streets and 120 mounds were apparently laid out according to their builders’ spiritual principles and view of the cosmos. To explore Cahokia is to re-experience the wonder of a vanished civilization and way of life.

Cahokia was abandoned around the year 1400 for reasons still unknown. But its surviving ruins remind us that the indigenous peoples of North America created monumental architecture, productive agriculture, domesticated a variety of crops, established thriving long-distance trade routes, and produced a wide range of political and social units.

West & Central Africa Prior to 1492

The overwhelming majority of non-Americans who would settle in the New World before 1820 were Africans. European settlers were outnumbered three or even four times by the number of Africans forcibly brought to the New World as slaves between 1500 and 1800. Clearly, to understand American history, it is essential to look closely at the African background.

Today, there is a tendency among many Westerners to associate sub-Saharan Africa with poverty and disease. Such a view, utterly misleading today, is also inappropriate when thinking about Africa in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

Although sub-Saharan Africa includes some of the poorest parts of the world today, it was not impoverished in this period. Textile and iron and steel production were extensive and trade was substantial, certainly equivalent to the levels achieved in Europe. Infant and adult death rates were no higher than in Europe and the quality of housing was similar. Nor was Europe superior militarily to the peoples it encountered in West and Central Africa. Repeatedly, African forces would defeat European intruders during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. There was no “Third World” in the fifteenth century.

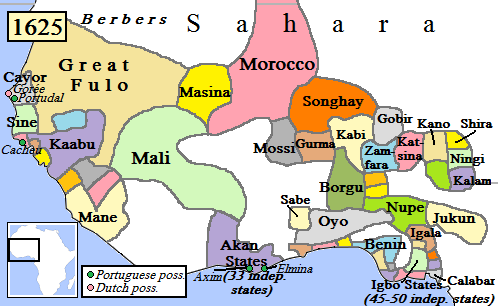

Nor would it be correct to describe sub-Saharan Africa on the eve of the Age of Discovery as a land of “tribes.” West and Central Africa in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries were divided into states as well as along both ethnolinguistic and political lines. Linguistic, ethnic, and kinship groups extended across political divides and many states contained multiple ethnic groups.

The states had the powers and authority associated with governments today, including the power to tax, wage war, enact laws, and adjudicate disputes. But authority was highly splintered. Unlike western Europe, where kingdoms such as France or Spain had achieved a degree of authority over various provinces, many parts of Western and Central Africa, especially along the Atlantic coast, were divided into tiny but sovereign states that were small both in terms of territory and population. Many of these states were no larger than a present-day county in the United States. About 70 percent of the Sub-Saharan African population lived in mini-states. The remaining 30 percent of the population, especially in the interior, lived in larger states or empires, such as Mali or Songhai, which later gave way to the Empire of Great Fula and the kingdoms of Segu and Kaarta.

Scholars today can identify some 200 independent states that existed in 1600 in the areas that would become enmeshed in the slave trade. The actual number of states may well have been 50 percent greater.

As in Europe, the states of West and Central African contained distinct social classes. Division among the rich and poor tended to be hereditary. Political power resided in the hands of political elites that made crucial decisions about war, law, or trade. Sometimes political power was concentrated among a very small number of individuals; at other times, the decision-making elite was broader.

It is important to note that some members of the elites owned slaves in the period prior to extensive contact with Europeans. Indeed, in this part of Africa individuals did not own land, which was owned collectively, and ownership of people was the primary way that elites accumulated wealth. Although deemed slaves, these people often occupied a status similar to that of serfs in Europe.

Prior to the sixteenth century, wars took place in Western and Central Africa for the same reasons they occurred in Europe: To expand or consolidate a state’s power, acquire new sources of revenue or territory, control trade, and assert central authority. Also, as in Europe, there were civil wars often fought over issues of political succession. There were raiders, generally nomads from the southern Sahara Desert, who might stage attacks, especially when the authority of a state was weak.

Unlike the Americas, Africa would not be conquered or settled by Europeans in the fifteenth or sixteenth (or seventeenth or eighteenth) centuries. Europeans did colonize some islands off the African coast, including Sao Tome, Principe, the Cape Verde Islands, Madeira, and the Azores. And the Portuguese did manage to establish a small colony in Angola. But apart from those limited acquisitions, Europeans were confined to small trading posts along the West African coast.

With the exception of a relatively small number of pirates and raiders, Europeans for the most part did not directly enslave individuals. Instead, European merchants relied on trading relations with various elites and gangs of bandits. Here it is important to note that not all West or Central African states participated in the slave trade and that the elites that did participate in the trade rarely sold their own people into slavery and had complicated motives for selling slaves, including the desire to deport those whom they had fought in wars. Yet if Europeans did not succeed in conquering large portions of Africa before the middle of the nineteenth century when the Industrial Revolution had greatly augmented European military power, European slave traders would, nevertheless, be able to exploit the existing political divisions within the region.