The New England Puritans

The New England Puritans

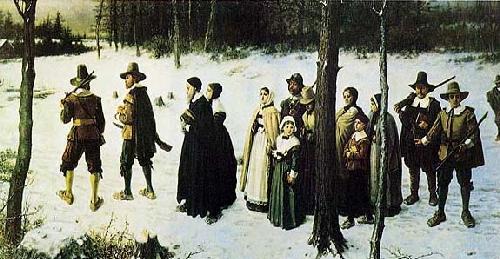

When Americans think about colonial New England, the group that commonly comes to mind is not the Puritans, but the Pilgrims, who landed at Plymouth Rock in 1620, held the first Thanksgiving in the autumn of 1621, and founded Plymouth Colony in what is now southeastern Massachusetts. In fact, the Pilgrims were far less influential than the Puritans, a group that began to arrive in New England a decade later.

The Pilgrims thought of themselves as simple Christians who wanted to escape the corruptions of the outside world. These people first fled from England to Amsterdam, then to Leyden, a Dutch university town, but found the corrupting world too much even there. They decided to move again, considering various alternatives including Guyana on the northern coast of South America. They finally settled on Virginia, but they landed by mistake on what is now Cape Cod. So weak was the loyalty of the second and third generations of Pilgrims to Plymouth that in 1691 the region became part of Massachusetts Bay Colony, the home of the Puritans.

Today, there are no Puritans, and certain Puritan beliefs are distinctly out of fashion. Large majorities of contemporary Americans believe people are basically good. The Puritans, in contrast, believed that most people were doomed to eternal damnation. Most adults today believe in childhood innocence. The Puritans, in contrast, believed in infant depravity—that even newborns were tainted by the sinfulness of Adam and Eve and were therefore bound for Hell. Privacy is an important value today. In Puritan New England, in contrast, watchmen called Selectmen kept an eye on every ten or twelve households.

Yet no group has played a more pivotal role in shaping American values than the New England Puritans. The seventeenth-century Puritans contributed to our country’s sense of mission, its work ethic, and its moral sensibilities. Today, 8 million Americans can trace their ancestry to the 15 to 20 thousand Puritans who migrated to New England between 1629 and 1640, but the impact of Puritanism is far greater.

Few people, however, have been as frequently subjected to caricature and ridicule than the Puritans. The journalist, H.L. Mencken, defined Puritanism as “the haunting fear that someone, somewhere, might be happy.” Particularly during the 1920s, the Puritans came to symbolize every cultural characteristic that “modern” Americans despised. The Puritans were often dismissed as drably-clothed religious zealots who were hostile to the arts and were eager to impose their rigid “Puritanical” morality on the world around them.

This stereotypical view is almost wholly incorrect. Contrary to much popular thinking, the Puritans were not sexual prudes. Although they strongly condemned sexual relations outside of marriage—levying fines or even whipping those who fornicated, committed adultery or sodomy, or bore children outside of wedlock—they attached a high value to the marital tie. Nor did Puritans abstain from alcohol; even though they objected to drunkenness, they did not believe alcohol was sinful in itself. They were not opposed to artistic beauty; although they were suspicious of the theater and the visual arts, the Puritans valued poetry. Indeed, John Milton (1603-1674), one of England’s greatest poets, was a Puritan. Even the association of the Puritans with drab colors is wrong. They especially liked the colors red and blue.

Although the Puritans wanted to reform the world to conform to God’s law, they did not set up a church-run state. Even though they believed that the primary purpose of government was to punish breaches of God’s laws, few people were as committed as the Puritans to the separation of church and state. Not only did they reject the idea of establishing a system of church courts, they also forbade ministers from holding public office.

Perhaps most strikingly, the Puritans in Massachusetts held annual elections and extended the right to vote and hold office to all “freemen.” Although this term was originally restricted to church members, it meant that a much larger proportion of the adult male population could vote in Massachusetts than in England itself (roughly 55 percent, compared to about 33 percent in England).

Who Were the Puritans?

In sixteenth-century England, a religious movement known as Puritanism arose which wanted to purge the Church of England of all vestiges of Roman Catholicism. The Puritans objected to elaborate church hierarchies and to church ceremonies and practices which lacked Biblical sanction and which elevated priests above their congregation. Thus the Puritans refused to celebrate Christmas because the Bible did not state that Christ was born on December 25.

Families in Colonial America

History Through…

…Rhymes: What the Puritans Believed

The word Puritan first entered the English language in the 1560s, around the time of William Shakespeare’s birth. It was a disparaging nickname for moral zealots who were hostile toward dancing, sports, fashion, and luxury. Puritans were especially put off by the theater, where bawdy plays, filled with blasphemy, featured men dressed as women and attracted an audience that included lewd women and idle apprentices.

By 1600, Puritans were members of a religious sect with specific beliefs. For one thing, the Puritans believed in Predestination—that before people were born, God had determined whether they would be saved or damned to Hell. A rhyme captured the Puritan belief that God and God alone decided human salvation:

You can and you can’t You will and you won’t You’ll be damned if you do You’ll be damned if you don’t.

The Puritans also believed in divine omnipotence: That God and God alone determined whether an individual would be saved or damned. No good works let alone wealth would ensure salvation.

The Puritans tended to divide life into a series of dualities. People were either among the Elect or the Damned. Life was divided between that which is religious and that which is secular. The Sabbath needed to be kept separate from weekdays. The church needed to be separate from the state.

Puritan beliefs might seem abstract, but they were not. Puritanism was a revolutionary ideology. It represented a radical attack on England as it existed at the beginning of the seventeenth century. It attacked England’s social, political, and religious hierarchy. Many Puritans called for a Parliament controlled by Puritans and the abolition of the Church of England’s hierarchy. The Puritans believed that God had chosen an aristocracy of the spirit that should rule over the earthy aristocracy of noble birth. The Puritans were not democrats. They believed in a hierarchy in which women were to obey their husbands and servants were to obey their masters. Nevertheless, the Puritans posed a challenge to the existing social hierarchy.

Puritans also represented a response to disruptive social and economic developments. At a time when England was undergoing unsettling transformations—as its population rose, poverty spread, and land became treated as a form of private property—the Puritans wanted to restore a sense of stable community that obeyed God’s laws.

History Through…

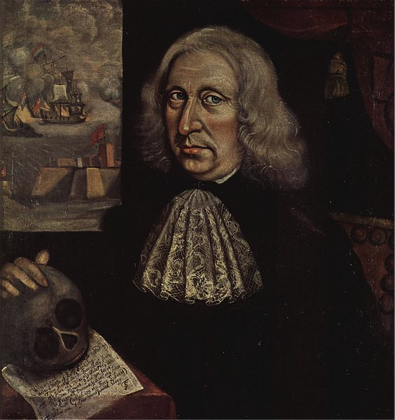

…Art: What America’s First Self Portrait Tells Us about Puritan Values

Why should I the World be minding therein a World of Evils Finding Then Farewell World: Farewell thy Jarres thy Joies thy Toies thy Wiles thy Warrs Truth Sounds Retreat: I am not sorye. The Eternal Drawes to him my heart By Faith (which can thy Force Subvert) To Crowne me (after Grace) with Glory.