Popular Attacks on Privilege

Popular Attacks on Privilege

A democratic impulse swept the country in the 1820s, It was apparent in widespread attacks on special privilege and aristocratic pretension. Established churches, the bench, and the legal and medical professions saw their elitist status diminished.

Connecticut and Massachusetts became the last states to repeal taxes that supported the states’ established churches, in 1819 and 1833 respectively.

The judiciary became more responsive to public opinion through election, rather than appointment of judges. To open up the legal profession, many states dropped formal training requirements to practice law. Some states also abolished training and licensing requirements for physicians, allowing unorthodox “herb and root” doctors, including many women, to compete with established physicians.

The surge of democratic sentiment had an important political consequence: the breakdown of the politics of deference and its terminology. The eighteenth-century language of politics—which included such terms as “faction,” “junto,” and “caucus”–was rooted in an elite-dominated political order. During the first quarter of the nineteenth century, a new democratic political vocabulary emerged that drew its words from everyday language. Instead of “standing” for public office, candidates “ran” for office. Politicians “log-rolled” (made deals) or “straddled the fence” or promoted “pork barrel” legislation (programs that would benefit their constituents).

The Masons

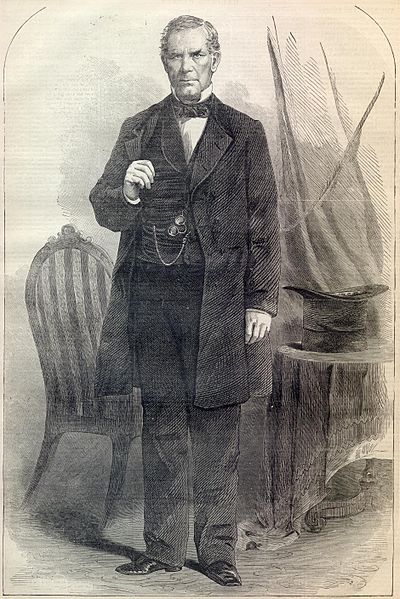

During the first quarter of the nineteenth century, local elites lost much of their influence. They were replaced by professional politicians. In the 1820s, political innovators, such as Martin Van Buren, the son of a tavernkeeper, and Thurlow Weed, a newspaper editor in Albany, New York, devised new campaign tools, such as torchlight parades, subsidized partisan newspapers, and nominating conventions. These political bosses and manipulators soon discovered that the most successful technique for arousing popular interest in politics was to attack a privileged group or institution that had used political influence to attain power or profit.

The “Anti-Masonic party” was the first political movement to win widespread popular following using this technique. In the mid-1820s, a growing number of people in New York and surrounding states had come to believe that members of the fraternal order of Freemasons, who seemed to monopolize many of the region’s most prestigious political offices and business positions, had used their connections to enrich themselves. They noted, for instance, that Masons held twenty-two of the nation’s twenty-four governorships.

Then, in 1826, in the small town of Batavia, New York, William Morgan, a former Mason, disappeared. Morgan had written an exposé of the organization in violation of the order’s vow of silence, and rumor soon spread that he had been tied up with heavy cables and dumped into the Niagara River. When no indictments were brought against the alleged perpetrators of Morgan’s kidnapping and presumed murder, many upstate New Yorkers accused local constables, justices of the peace, and judges, who were members of the Masons, of obstruction of justice.

By 1830, the Anti-Mason movement had succeeded in capturing half the vote in New York State and had gained substantial support throughout New England. In the mid-1830s, the Anti-Masons were absorbed into a new national political party, the Whigs. Among the Anti-Mason movement’s contributions to American politics was the first national nominating convention.