Introduction: The Jacksonian Era

Whose Portrait Should be on the $20 Bill?

The $20 bill features President Andrew Jackson, a slaveowner who prohibited the delivery of antislavery literature to the South. He removed tens of thousands of Native Americans from their homelands, resulting in thousands of deaths.

It is no wonder that many people want Andrew Jackson removed from the $20 bill.

But there is also another side to the story. President Jackson made American politics democratic. He championed the interests of frontier farmers and urban laborers.

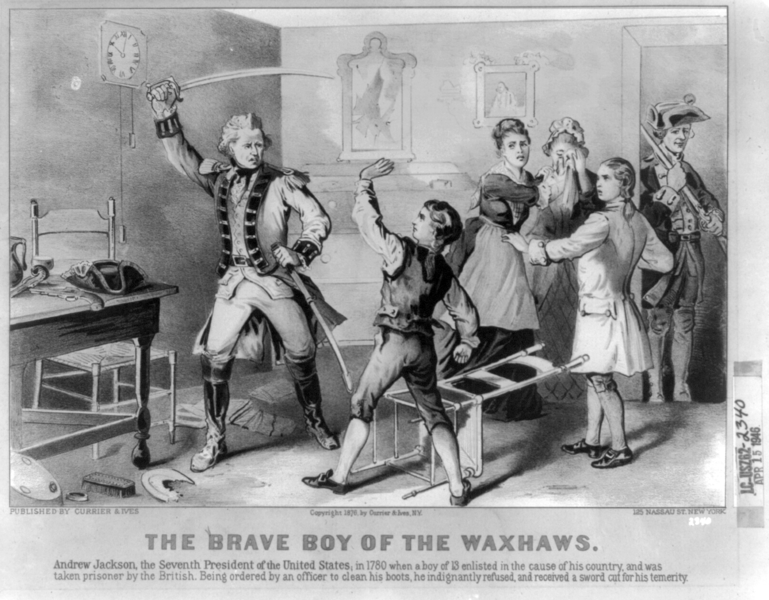

His life story was unlike that of any previous president. He was the first born in a log cabin in what was then the West. Born in the mountains along the North and South Carolina border, he was left fatherless shortly after birth. During the American Revolution, his mother and two brothers died, leaving him an orphan at the age of fourteen. In his mid-teens, he engaged in guerilla warfare against the British in the Carolina backcountry.

He subsequently moved to Tennessee where, as a Representative and a Senator, he played a crucial role in bringing the West into national politics. He even took the then-radical position of calling for a tax on slaves.

He gained fame as a general, defeating the British at New Orleans in the last major battle of the War of 1812, driving the Spanish out of Florida, and helping to secure U.S. control of the Gulf Coast through his defeat of the Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. After that battle, he adopted a Creek infant who had been left orphaned and raised him as his own son.

One of the founders of the Democratic party, he later changed the process for nominating presidential candidates. Instead of letting members of Congress choose the candidates, he brought the process closer to the people by favoring state nominating conventions, and later popularized the national presidential nominating convention.

As president, he took a series of steps that helped democratize American politics. After his election, he invited the public to the White House to celebrate. He also argued forcefully for the spoils system (which he called “rotation in office”), arguing that after an election, a new president should bring in new officeholders. He was also the first to argue that the president, not Congress, was the true representative of the people and had an obligation to fight for their interests.

Among the central issues of his presidency was his war against the second Bank of the United States, which he believed favored the wealthy at the expense of struggling debtors. After vetoing the recharter of the bank, he issued an impassioned message in which he articulated egalitarian principles: That the federal government should reject any measure that makes the rich richer and the potent more powerful,” or harm “the humble members of society—the farmers, mechanics, and laborers—who have neither the time nor the means of securing like favors to themselves.”

When South Carolina threatened to nullify a federal law, Jackson responded forcefully. He made it clear that any attempt to resist federal authority would be met by force—establishing the precedent that led President Abraham Lincoln to resist secession three decades later.

The Rise of the Democratic Politics

When James Monroe began his second term as president in 1821, he rejoiced at the idea that the country was no longer divided by political parties, which he considered “the curse of the country,” breeding disunity, demagoguery, and corruption. Yet even before Monroe’s second term had ended, new political divisions had already begun to evolve, creating an increasingly democratic system of politics.

In 1821, American politics were still largely dominated by deference. Competing political parties were nonexistent and voters generally deferred to the leadership of local elites or leading families. Political campaigns tended to be relatively staid affairs. Direct appeals by candidates for support were considered in poor taste. Election procedures were, by later standards, quite undemocratic. Most states imposed property and taxpaying requirements on the white adult males who alone had the vote, and they conducted voting by voice. Presidential electors were generally chosen by state legislatures. Given the fact that citizens had only the most indirect say in the election of the president, it is not surprising that voting participation was generally extremely low, amounting to less than 30 percent of adult white males.

Between 1820 and 1840, a revolution took place in American politics. In most states, property qualifications for voting and officeholding were repealed and voting by voice was largely eliminated. Direct methods of selecting presidential electors, county officials, state judges, and governors replaced indirect methods. Because of these and other political innovations, voter participation skyrocketed. By 1840, voting participation had reached unprecedented levels. Nearly 80 percent of adult white males went to the polls.

A new two-party system, made possible by an expanded electorate, replaced the politics of deference and leadership by elites. By the mid-1830s, two national political parties with marked philosophical differences, strong organizations, and wide popular appeal competed in virtually every state. Professional party managers used partisan newspapers, speeches, parades, rallies, and barbecues to mobilize popular support. Our modern political system had been born.

The Expansion of Voting Rights

The most significant political innovation of the early nineteenth century was the abolition of property qualifications for voting and officeholding. Hard times resulting from the Panic of 1819 led many people to demand an end to property restrictions on voting and officeholding. In New York, for example, fewer than two adult males in five could legally vote for senators or the governor. Under the new state constitution adopted in 1821, all adult white males were allowed to vote, as long as they paid taxes or had served in the militia.

Five years later, an amendment to the state’s constitution eliminated the taxpaying and militia qualifications, thereby establishing universal white male suffrage. By 1840, universal white manhood suffrage had largely become a reality. Only three states— Louisiana, Rhode Island, and Virginia— still restricted the suffrage to white male property owners and taxpayers.

In order to encourage popular participation in politics, most states also instituted statewide nominating conventions and then the first national presidential nominating conventions, opened polling places in more convenient locations, extended the hours that polls were open, and eliminated the earlier practice of voting by voice. This last reform did not truly institute the secret ballot, which was adopted beginning in the 1880s, since voters during the mid-nineteenth century usually voted with straight-ticket paper ballots prepared by the political parties themselves. Each party had a different-colored ballot, which voters deposited in a publicly viewed ballot box, so that those present knew who had voted for which party.

By 1824, only six of the nation’s twenty-four states still chose presidential electors in the state legislature, and eight years later the only state still to do so was South Carolina, which continued this practice until the Civil War. In addition to removing property and tax qualifications for voting and officeholding, states also reduced residency requirements for voting. Immigrant males were permitted to vote in most states if they had declared their intention to become citizens. During the nineteenth century, twenty-two states and territories permitted immigrants who were not yet naturalized citizens to vote. States also allowed voters to choose presidential electors, governors, and county officials.

While universal white male suffrage was becoming a reality, restrictions on voting of African Americans and women remained in place. Only one state, New Jersey, had given unmarried female property holders the right to vote following the Revolution, but the state rescinded this right at the time it extended suffrage to all adult white men. Most states also explicitly denied the right to vote to free African Americans. By 1858, free blacks were eligible to vote in just four northern states: New Hampshire, Maine, Massachusetts, and Vermont.