The Election of 1860

The Lincoln-Douglas Debates

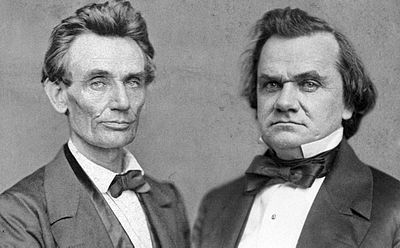

The critical issues dividing the nation—slavery versus free labor, popular sovereignty, and the legal and political status of black Americans—were brought into sharp focus in a series of dramatic debates during the 1858 election campaign for U.S. senator from Illinois. The campaign pitted a little-known lawyer from Springfield named Abraham Lincoln against Senator Stephen A. Douglas, the front runner for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1860.

The public knew little about the man the Republicans selected to run against Douglas. Lincoln had been born on February 12, 1809, in a log cabin near Hodgenville, Kentucky, and he grew up on the wild Kentucky and Indiana frontier. At the age of 21, he moved to Illinois, where he worked as a clerk in a country store, volunteered to fight Indians in the Black Hawk War, became a local postmaster and a lawyer, and served four terms in the lower house of the Illinois General Assembly.

A Whig in politics, Lincoln was elected in 1846 to the U.S. House of Representatives, but his stand against the Mexican War had made him too unpopular to win reelection. After the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, Lincoln reentered politics, and in 1858 the Republican Party nominated him to run against Douglas for the Senate.

Lincoln accepted the Republican nomination with the famous words: “‘A house divided against itself cannot stand.’ I believe this Government cannot endure permanently half-slave and half-free.” He did not believe the Union would fall, but he did predict that it would cease to be divided. Lincoln proceeded to argue that Stephen Douglas’s Kansas-Nebraska Act and the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision were part of a conspiracy to make slavery lawful “in all the States, old as well as new—North as well as South.”

For four months Lincoln and Douglas crisscrossed Illinois, traveling nearly 10,000 miles and participating in seven face-to-face debates before crowds of up to 15,000.

Douglas’s strategy in the debates was to picture Lincoln as a fanatical “Black Republican” whose goal was to incite civil war, to emancipate the slaves, and to make blacks the social and political equals of whites.

Lincoln denied that he was a radical. He said that he supported the Fugitive Slave Law and opposed any interference with slavery in the states where it already existed.

During the course of the debates, Lincoln and Douglas presented two sharply contrasting views of the problem of slavery. Douglas argued that slavery was a dying institution that had reached its natural limits and could not thrive where climate and soil were inhospitable. He asserted that the problem of slavery could best be resolved if it were treated as essentially a local problem.

Lincoln, on the other hand, regarded slavery as a dynamic, expansionistic institution, hungry for new territory. He argued that if Northerners allowed slavery to spread unchecked, slaveowners would make slavery a national institution and would reduce all laborers, white as well as black, to a state of virtual slavery.

The sharpest difference between the two candidates involved the issue of black Americans’ legal rights. Douglas was unable to conceive of blacks as anything but inferior to whites, and was unalterably opposed to Negro citizenship. “I want citizenship for whites only,” he declared. Lincoln said that he, too, was opposed to “bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races.” But he insisted that black Americans were equal to Douglas and “every living man” in their right to life, liberty, and the fruits of their own labor.

The debates reached a climax on a damp, chilly August 27. At Freeport, Illinois, Lincoln asked Douglas to reconcile the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision, which denied Congress the power to exclude slavery from a territory, with popular sovereignty. Could the residents of a territory “in any lawful way” exclude slavery prior to statehood?

Douglas replied by stating that the residents of a territory could exclude slavery by refusing to pass laws protecting slaveholders’ property rights. “Slavery cannot exist a day or an hour anywhere,” he declared, “unless it is supported by local police regulations.”

Lincoln had maneuvered Douglas into a trap. Any way he answered, Douglas was certain to alienate Northern Free Soilers or proslavery Southerners. The Dred Scott decision had given slaveowners the right to take their slavery into any western territories. Now Douglas said that territorial settlers could exclude slavery, despite what the Court had ruled. Douglas won reelection, but his cautious statements antagonized Southerners and Northern Free Soilers alike.

In the fall election of 1858, the general public in Illinois did not have an opportunity to vote for either Lincoln or Douglas because the state legislature, and not individual voters, actually elected the Illinois senator. In the final balloting, the Republicans outpolled the Democrats. But, the Democrats had gerrymandered the voting districts so skillfully that they kept control of the state legislature.

Although Lincoln failed to win a Senate seat, his battle with Stephen Douglas had catapulted him into the national spotlight and made him a serious presidential possibility in 1860. As Lincoln himself noted, his defeat was “a slip and not a fall.”

Harpers Ferry

On August 19, 1859, John Brown, the Kansas abolitionist, and Frederick Douglass, the celebrated black abolitionist and former slave, met in an abandoned stone quarry near Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. For three days, the two men discussed whether violence could be legitimately used to free the nation’s slaves.

The Kansas guerrilla leader asked Douglass if he would join a band of raiders who would seize a federal arsenal and spark a mass uprising of slaves. “When I strike,” Brown said, “the bees will begin to swarm, and I shall need you to help hive them.”

“No,” Douglass replied. Brown’s plan, he knew, was suicidal. Brown had earlier proposed a somewhat more realistic plan. According to that scheme, Brown would have launched guerrilla activity in the Virginia mountains, providing a haven for slaves and an escape route into the North. That scheme had a chance of working, but Brown’s new plan was hopeless.

Up until the Kansas-Nebraska Act, abolitionists were averse to the use of violence. Opponents of slavery hoped to use moral suasion and other peaceful means to eliminate slavery. But by the mid-1850s, the abolitionists’ aversion to violence had begun to fade. On the night of October 16, 1859, violence came, and John Brown was its instrument.

As early as 1857, John Brown had begun to raise money and recruit men for an invasion of the South. Brown told his backers that only through insurrection could this “slave-cursed Republic be restored to the principles of the Declaration of Independence.”

Brown’s plan was to capture the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia), and arm slaves from the surrounding countryside. His long-range goal was to drive southward into Tennessee and Alabama, raiding federal arsenals and inciting slave insurrections. Failing that, he hoped to ignite a sectional crisis that would destroy slavery.

At 8 o’clock Sunday evening, October 16, John Brown led a raiding party of approximately 22 men toward Harpers Ferry, where they captured the lone night watchman and cut the town’s telegraph lines. Encountering no resistance, Brown’s raiders seized the federal arsenal, an armory, and a rifle works along with several million dollars worth of arms and munitions. Brown then sent out several detachments to round up hostages and liberate slaves.

But Brown’s plan soon went awry. During the night, a church bell began to toll, warning neighboring farmers and militiamen from the surrounding countryside that a slave insurrection was under way. Local townspeople arose from their beds and gathered in the streets, armed with axes, knives, and squirrel rifles. Within hours, militia companies from villages within a 30-mile radius of Harpers Ferry cut off Brown’s escape routes and trapped Brown’s men in the armory.

Twice, Brown sent men carrying flags of truce to negotiate. On both occasions, drunken mobs, yelling “Kill them, Kill them,” gunned the men down.

John Brown’s assault against slavery lasted less than two days. Early Tuesday morning, October 18, U.S. Marines, commanded by Colonel Robert E. Lee and Lieutenant J.E.B. Stuart, arrived in Harpers Ferry. Brown and his men took refuge in a fire engine house and battered holes through the building’s brick wall to shoot through. A hostage later described the climactic scene:

With one son dead by his side and another shot through, he felt the pulse of his dying son with one hand and held his rifle with the other and commanded his men, encouraging them to fire and sell their lives as dearly as they could.

Later that morning, Colonel Lee’s Marines stormed the engine house and rammed down its doors. Brown and his men continued firing until the leader of the storming party cornered Brown and knocked him unconscious with a sword. Five of Brown’s party escaped, ten were killed, and seven, including Brown himself, were taken prisoner.

A week later, John Brown was put on trial in a Virginia court, even though his attack had occurred on federal property. During the six-day proceedings, Brown refused to plead insanity as a defense. He was found guilty of treason, conspiracy, and murder, and was sentenced to die on the gallows.

The trial’s high point came at the very end when Brown was allowed to make a five-minute speech. His words helped convince thousands of Northerners that this grizzled man of 59, with his “piercing eyes” and “resolute countenance,” was a martyr to the cause of freedom. Brown denied that he had come to Virginia to commit violence. His only goal, he said, was to liberate the slaves:

If it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice and mingle my blood with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments, I say let it be done.

Brown’s execution was set for December 2. Before he went to the gallows, Brown wrote one last message: “I…am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.” At 11 A.M., he was led to the execution site, a halter was placed around his neck, and a sheriff led him over a trapdoor. The sheriff cut the rope and the trapdoor opened. As the old man’s body convulsed on the gallows, a Virginia officer cried out: “So perish all enemies of Virginia!”

Across the North, church bells tolled, flags flew at half-mast, and buildings were draped in black bunting. Ralph Waldo Emerson compared Brown to Jesus Christ and declared that his death had made “the gallows as glorious as the cross.” William Lloyd Garrison, previously the strongest exponent of nonviolent opposition to slavery, announced that Brown’s death had convinced him of “the need for violence” to destroy slavery. He told a Boston meeting that “every slave holder has forfeited his right to live,” if he opposed immediate emancipation.

Prominent Northern Democrats and Republicans, including Stephen Douglas and Abraham Lincoln, spoke out forcefully against Brown’s raid and his tactics. Lincoln expressed the views of the Republican leadership, when he denounced Brown’s raid as an act of “violence, bloodshed, and treason” that deserved to be punished by death. But Southern whites refused to believe that politicians like Lincoln and Douglas represented the true opinion of most Northerners. These men condemned Brown’s “invasion,” observed a Virginia senator, “only because it failed.”

The Northern reaction to John Brown’s raid convinced many white Southerners that a majority of Northerners wished to free the slaves and incite a race war. Southern extremists, known as “fire-eaters,” told large crowds that John Brown’s attack on Harpers Ferry was “the first act in the grand tragedy of emancipation, and the subjugation of the South in bloody treason.”

After Harpers Ferry, Southerners increasingly believed that secession and creation of a slaveholding confederacy were now the South’s only options. A Virginia newspaper noted that there were “thousands of men in our midst who, a month ago, scoffed at the idea of dissolution of the Union as a madman’s dream, but who now hold the opinion that its days are numbered.”

The Election of 1860

In April 1860, the Democratic Party assembled in Charleston, South Carolina to select a presidential nominee. Southern delegates insisted that the party endorse a federal code to guarantee the rights of slaveholders in the territories. When the convention rejected the proposal, delegates from the deep South walked out. The remaining delegates reassembled six weeks later in Baltimore and selected Stephen Douglas as their candidate. Southern Democrats proceeded to choose John C. Breckinridge as their presidential nominee.

In May, the Constitutional Union Party, which consisted of conservative former Whigs, Know Nothings, and pro-Union Democrats nominated John Bell of Tennessee for President. This short-lived party denounced sectionalism and tried to rally support around a platform that supported the Constitution and the Union. Meanwhile, the Republican Party nominated Abraham Lincoln on the third ballot.

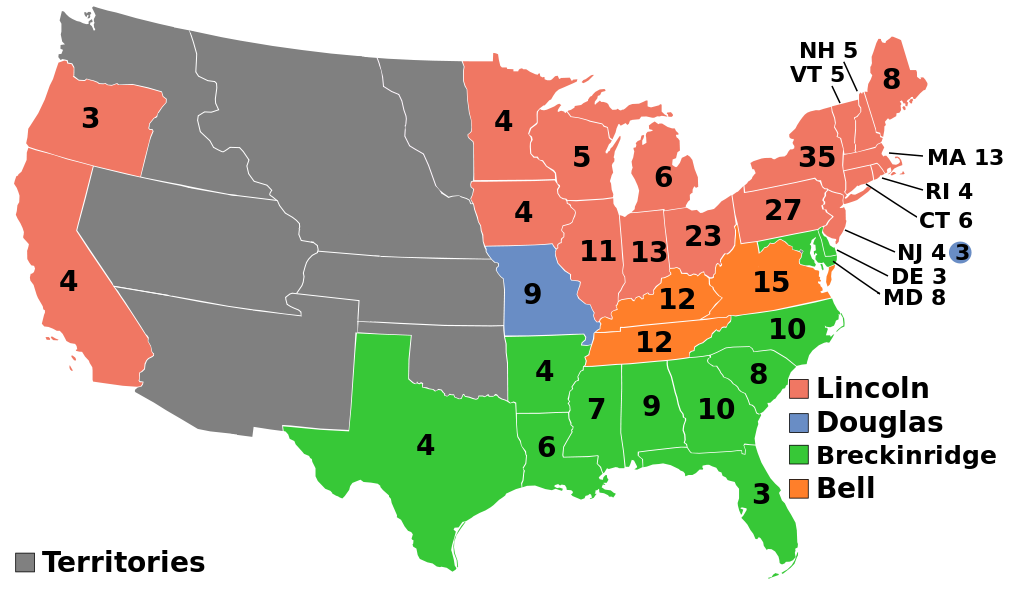

The 1860 election revealed how divided the country had become. There were actually two separate sectional campaigns: one in the North, pitting Lincoln against Douglas, and one in the South between Breckinridge and Bell. Only Stephen Douglas mounted a truly national campaign. The Republicans did not campaign in the South and Lincoln’s name did not appear on the ballot in ten states.

In the final balloting, Lincoln won only 39.9 percent of the popular vote, but received 180 Electoral College votes, 57 more than the combined total of his opponents. He failed to receive a single electoral college vote in the South.

Historical Debates

America’s Worst Presidents

Academic historians consistent rank Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan as among the United States’s worst presidents. Pierce was president when two of the most divisive initiatives in U.S. history took place: Enactment of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which repealed the Missouri Compromise and revived the slavery issue in American politics, and the Ostend Manifesto, advocating the U.S. annexation of Cuba, which had tens of thousands of slaves, from Spain.

Buchanan, in turn, was a weak leader, whose inactions helped to intensify sectional tensions and did little to oppose secession of the Southern states. He meddled in the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision, which denied that African-Americans were citizens, mistakenly believing the case would settle the slavery issue. He also urged Congress to support a pro-slavery government in Kansas that did not have broad support among Kansas’s settlers.

Worse yet, he considered secession illegal and unwise, but declared that the federal government could not legally prevent the Southern states from leaving the Union. In taking this position, he violated his pledge to protect the U.S. Constitution. In his State of the Union address, he laid out his reasoning: “All for which the slave States have ever contended, is to be let alone and permitted to manage their domestic institutions in their own way. As sovereign States, they, and they alone, are responsible before God and the world for the slavery existing among them. For this the people of the North are not more responsible and have no more fight to interfere than with similar institutions in Russia or in Brazil.”

Nor did Buchanan prevent the shipment of arms and other supplies to the Southern states or reinforce federal installations in the region. He failed to avert the worst crisis in American history.