The Breakdown of the Party System

The Breakdown of the Party System

As late as 1850, the two-party system seemed healthy. Democrats and Whigs drew strength in all parts of the country. Then, in the early 1850s, the two-party system began to disintegrate in response to massive foreign immigration. By 1856, the Whig Party had collapsed and been replaced by a new sectional party, the Republicans.

Between 1846 and 1855, more than three million foreigners arrived in America. In cities such as Chicago, Milwaukee, New York, and St. Louis immigrants actually outnumbered native-born citizens. Opponents of immigration capitalized on working-class fear of economic competition from cheaper immigrant labor, and resentment against the growing political power of foreigners.

In 1849, a New Yorker named Charles Allen responded to this anti-Catholic hostility by forming a secret fraternal society made up of native-born Protestant working men. Allen called this secret society The Order of the Star Spangled Banner, and it soon formed the nucleus of a new political party known as the Know-Nothing or the American Party. The party received its name from the fact that when members were asked about the workings of the party, they were supposed to reply, “I know nothing.”

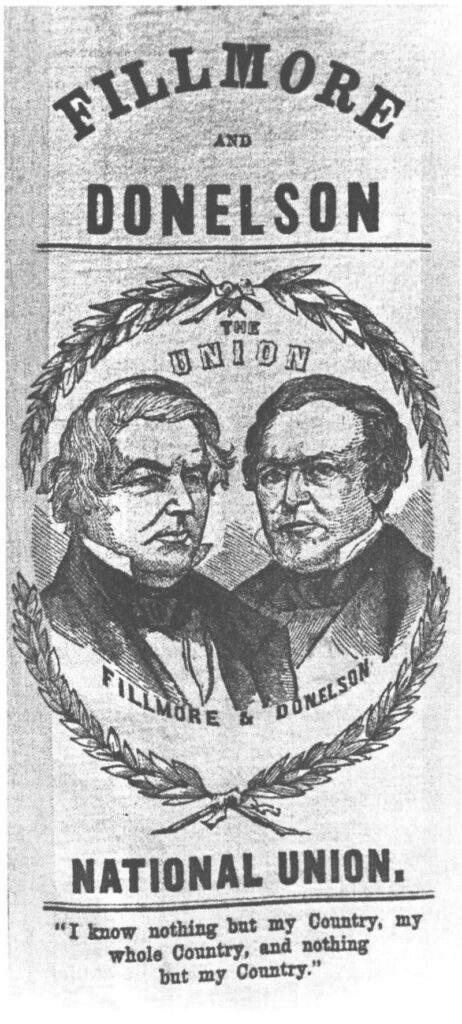

By 1855, the Know-Nothings had captured control of the legislatures in parts of New England and were the dominant opposition party to the Democrats in New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. In the presidential election of 1856, the party supported Millard Fillmore and won more than 21 percent of the popular vote and eight Electoral votes. In Congress, the party had five senators and 43 representatives. Between 1853 and 1855, the Know Nothings replaced the Whigs as the nation’s second largest party.

In 1855, Abraham Lincoln denounced the Know-Nothings in eloquent terms:

I am not a Know-Nothing. How could I be? How can anyone who abhors the oppression of Negroes be in favor of degrading classes of white people? Our progress in degeneracy appears to me pretty rapid, as a nation we began by declaring “all men are created equal.” We now practically read it, “all men are created equal, except Negroes.” When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read “all men are created equal, except Negroes, and foreigners, and Catholics.” When it comes to this I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretense of loving liberty-to Russia, for example, where despotism can be taken pure and without the base alloy of hypocrisy.

By 1856, the Know-Nothing Party was in decline. Many Know-Nothing officeholders were relatively unknown men with little political experience. In the states where they gained control, the Know Nothings proved unable to enact their legislative program, which called for:

- a 21-year residency period before immigrants could become citizens and vote;

- a limitation on political office holding to native-born Americans, and

- restrictions on liquor sales.

The rise and fall of the Know Nothing party contributed to the breakdown of the Second Party System. With the political parties weakened, it became increasingly difficult to reach compromises over the issue of slavery.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act

In 1854, a piece of legislation was introduced in Congress that shattered all illusions of sectional peace. The Kansas-Nebraska Act destroyed the Whig Party, divided the Democratic Party, and created the Republican Party. Ironically, the author of this legislation was Senator Stephen A. Douglas, who had pushed the Compromise of 1850 through Congress and had sworn after its passage that he would never make a speech on the slavery question again.

As chairman of the Senate Committee on Territories, Douglas proposed that the area west of Iowa and Missouri—which had been set aside as a permanent Indian reservation—be opened to white settlement. Southern members of Congress demanded that Douglas add a clause specifically repealing the Missouri Compromise, which would have barred slavery from the region. Instead, the status of slavery in the region would be decided by a vote of the region’s settlers. In its final form, Douglas’s bill created two territories, Kansas and Nebraska, and declared that the Missouri Compromise was “inoperative and void.” With solid support from Southern Whigs and Southern Democrats and the votes of half of the Northern Democrats, the measure passed.

Why did Douglas risk reviving the slavery question? His critics charged that the Illinois Senator’s chief interest was to win the Democratic presidential nomination in 1860 and to secure a right of way for a transcontinental railroad that would make Chicago the country’s transportation hub.

Douglas’s supporters pictured him as a proponent of western development and a sincere believer in popular sovereignty as a solution to the problem of slavery in the western territories. Douglas had long insisted that the democratic solution to the slavery issue was to allow the people who actually settled a territory to decide whether slavery would be permitted or forbidden. Popular sovereignty, he believed, would allow the nation to “avoid the slavery agitation for all time to come.”

In fact, by 1854 the political and economic pressure to organize Kansas and Nebraska had become overwhelming. Midwestern farmers agitated for new land. A southern transcontinental rail route had been completed through the Gadsden Purchase in December 1853, and promoters of a northern railroad route for a viewed territorial organization as essential. At the same time, Missouri slaveholders, already bordered on two sides by free states, believed that slavery in their state was doomed if they were surrounded by a free territory.

What if…

When Political Parties Splinter or Die

Twice in U.S. history, a political party has died. The first to die was the Federalist party in the early 1800s, followed by the demise of the Whig party in the 1850s.

Several other times, existing parties underwent a profound shift in their outlook and base of support. This happened to the Democratic party in the 1890s, in response to the rise of the Populist party, and in the late 1960s and 1970s, when many conservative Democrats left the party to join the Republicans.

Then, there are times when parties have splintered. This occurred during the election of 1912, when a Republican party split between William Howard Taft and Theodore Roosevelt allowed Democrat Woodrow Wilson to become president. In the 1920s, the Democratic party divided into pro- and anti-Ku Klux Klan factions. In 1948, white Southern Democrats ran their own “Dixiecrat” candidate for the presidency.