Slavery in a Capitalist World

Slavery in a Capitalist World

Why were the South’s political leaders so worried about whether slavery would be permitted in the West when geography and climate made it unlikely that slavery would ever prosper in the area? The answer lies in the South’s growing awareness of its minority status in the Union, of the elimination of slavery in many other areas of the Western Hemisphere, and of the decline of slavery in the upper South.

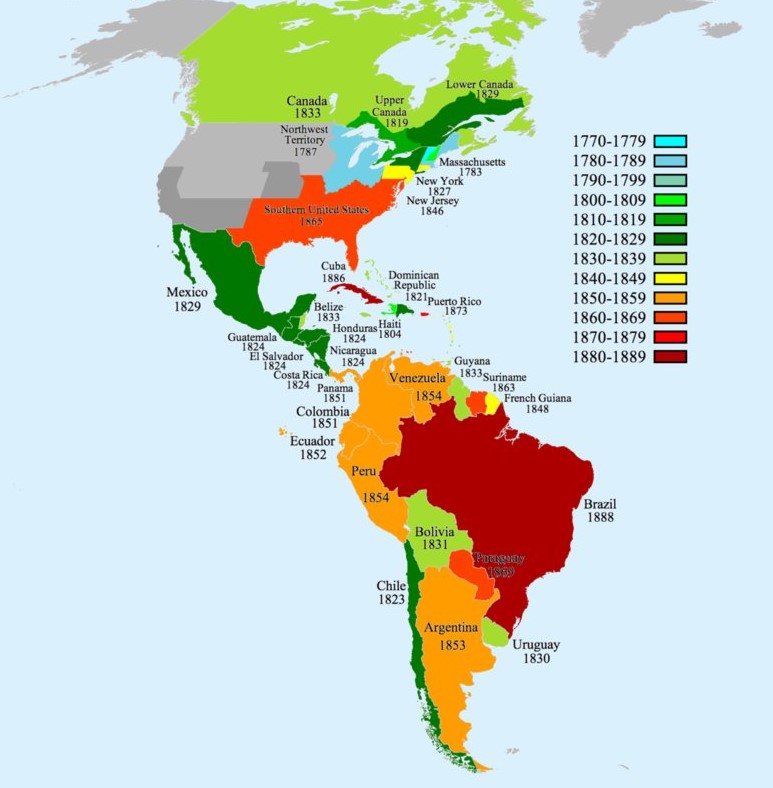

During the first half of the nineteenth century, slave labor was becoming an exception in the world. During the early years of the nineteenth century, Spain’s newly independent New World colonies abolished slavery. Then in 1833, Britain emancipated its slaves in Jamaica, Trinidad, Guiana, Saint Vincent, Saint Lucia, Tobago, Grenada, and Montserrat. A decade and a half later, France abolished slavery in its Caribbean colonies. By 1850, New World slavery was confined to Brazil, Cuba, Puerto Rico, a small number of Dutch colonies, and the American South.

British slave emancipation in the Caribbean was followed by an intensified campaign to eradicate the international slave trade. In areas like Brazil and Cuba, slavery could not long survive once the slave trade was cut off because the slave populations of these countries had a skewed sex ratio and were unable to naturally reproduce. Only in the American South could slavery survive without the Atlantic slave trade.

Exacerbating Southern fears about slavery’s future was a sharp decline in slavery in the upper South. Between 1830 and 1860, the proportion of slaves in Missouri’s population fell from 18 to 10 percent, in Kentucky from 24 to 19 percent, and in Maryland from 23 to 13 percent. The South’s leaders feared that in the future the upper South would soon become a region of free labor.

Within the region itself, slave ownership was increasingly concentrated in fewer and fewer hands. Abolitionists were stigmatizing the South as out of step with the times. Many of leading Southern politicians feared that these criticisms of slavery would weaken lower-class white support for slavery. Some white Southerners called for the reopening of the African slave trade. These people believed that nonslaveholding Southerners would only support slavery if they believed they had a chance of owning slaves themselves. But for most Southern leaders, the best way to demonstrate slavery’s viability was through westward expansion.

Historical Debates

The Compromise of 1850

Early on the evening of January 21, 1850, Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky trudged through the Washington, D.C. snow to visit Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts. Clay, 73 years old, was a sick man, wracked by a severe cough, but he braved the snowstorm because he feared for the Union’s future. For four years Congress bitterly and futilely debated the question of the expansion of slavery. Ever since David Wilmot proposed that slavery be prohibited from any territory acquired from Mexico, opponents of slavery had argued that Congress possessed the power to regulate slavery in all of the territories. Ardent proslavery Southerners vigorously disagreed.

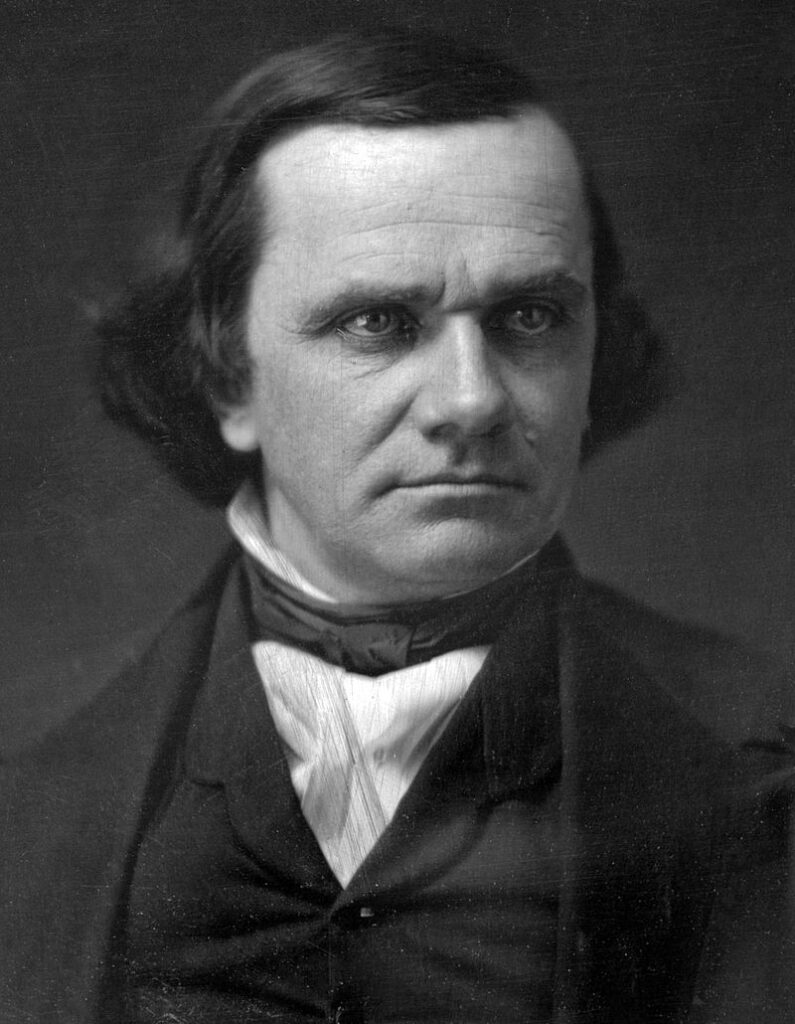

Politicians had repeatedly but unsuccessfully tried to work out a compromise. One simple proposal had been to extend the Missouri Compromise line to the Pacific Ocean. Thus, slavery would have been forbidden north of 36 30′ north latitude but permitted south of that line. This proposal attracted the support of moderate Southerners but generated little support outside the region. Another proposal, supported by two key Democratic senators, Lewis Cass of Michigan and Stephen Douglas of Illinois, was known as popular sovereignty. It declared that the people actually living in a territory should decide whether or not to allow slavery.

But neither suggestion offered a solution to the whole range of issues dividing the North and South. It was up to Henry Clay, who had just returned to Congress after a seven-year absence, to work out a formula that balanced competing sectional concerns.

For an hour, Clay outlined to Webster a complex plan to save the Union. A compromise could only be effective, he stated, if it addressed all the issues dividing North and South. He proposed that:

- California be admitted as a free state

- There be no restriction on slavery in New Mexico and Utah

- Texas relinquish its claim to land in New Mexico in exchange for federal assumption of Texas’s unpaid debts

- Congress enact a stringent and enforceable fugitive slave law

- The slave trade—but not slavery—be abolished in the District of Columbia.

A week later, Clay presented his proposal to the Senate. The aging statesman was known as the “Great Compromiser” for his efforts on behalf of the Missouri Compromise and the Compromise Tariff of 1832. which resolved the nullification crisis. Once again, he appealed to Northerners and Southerners to place national patriotism ahead of sectional loyalties.

Clay’s proposal ignited an eight-month debate in Congress and led John C. Calhoun to threaten Southern secession. Daniel Webster, the North’s most spellbinding orator, threw his support behind Clay’s compromise. “Mr. President,” he began, “I wish to speak today not as a Massachusetts man, nor as Northern man, but as an American…I speak today for the preservation of the Union. Hear me for my cause.” He concluded by warning his listeners that “there can be no such thing as a peaceable secession.”

Webster’s speech provoked outrage from Northern opponents of compromise. Senator William H. Seward of New York called Webster a “traitor to the cause of freedom,” but Webster’s speech reassured moderate Southerners that powerful interests in the North were committed to compromise.

Still, opposition to compromise was fierce. Whig President, Zachary Taylor, argued that California, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, and Minnesota should all be admitted to statehood before the question of slavery was addressed, a proposal that would have given the North a ten-vote majority in the Senate. William H. Seward denounced the compromise as conceding too much to the South and declared that there was a “higher law” than the Constitution, a law that demanded an end to slavery.

In July, Northern and Southern senators opposed to the very idea of compromise joined ranks to defeat a bill that would have admitted California to the Union and organized New Mexico and Utah without reference to slavery.

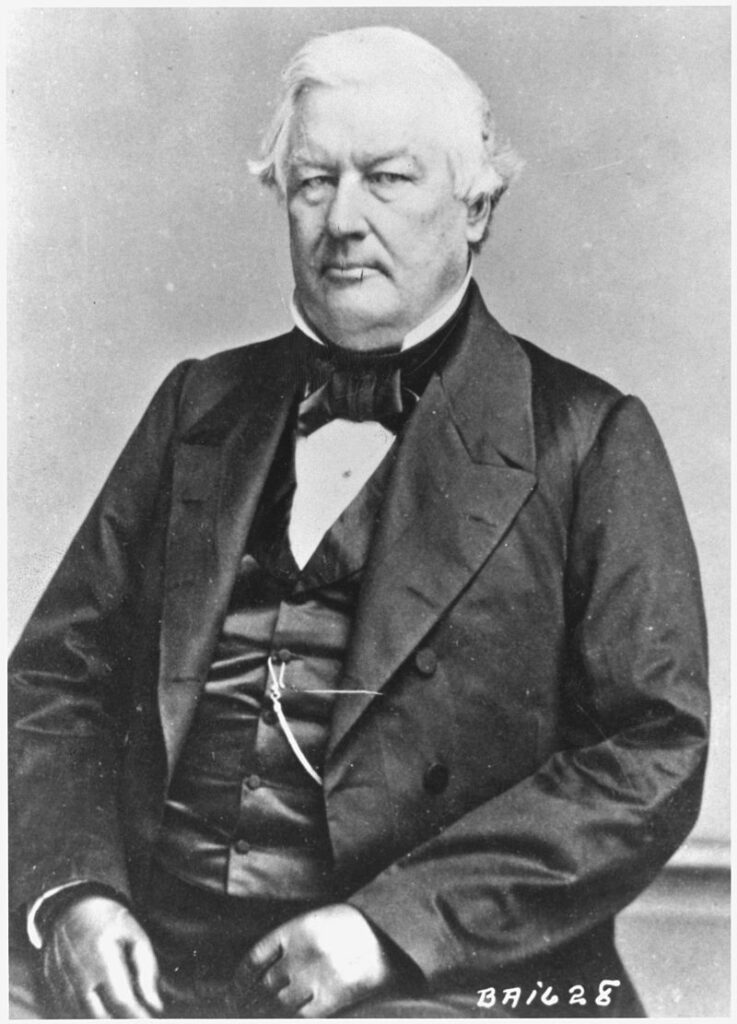

Compromise appeared to be dead. A bitterly disappointed and exhausted Henry Clay dejectedly left the Capitol, his efforts apparently for naught. Then with unexpected suddenness the outlook abruptly changed. On the evening of July 9, 1850, President Taylor died of gastroenteritis, five days after taking part in a Fourth of July celebration dedicated to the building of the still unfinished Washington Monument. Taylor’s successor, Millard Fillmore, was a 50-year-old New Yorker and an ardent supporter of compromise.

In Congress, leadership in the fight for a compromise passed to Stephen Douglas, a Democratic senator from Illinois. An arrogant and dynamic leader, five foot four inches in height with stubby legs, a massive head, bushy eyebrows, and a booming voice, Douglas was known as the “Little Giant.” Douglas abandoned Clay’s strategy of gathering all issues dividing the sections into a single bill. Instead, he introduced Clay’s proposals one at a time. In this way, he was able to gather support from varying coalitions of Whigs and Democrats and Northerners and Southerners on each issue.

At the same time, banking and business interests as well as speculators in Texas bonds lobbied and even bribed congressmen to support compromise. Despite these manipulations, the compromise proposals never succeeded in gathering solid congressional support. In the end, only four senators and twenty-eight representatives voted for every one of the measures. Nevertheless, they all passed.

As finally approved, the Compromise:

- Admitted California as a free state,

- Allowed the territorial legislatures of New Mexico and Utah to settle the question of slavery in those areas,

- Set up a stringent federal law for the return of runaway slaves,

- Abolished the slave trade in the District of Columbia, and

- Gave Texas $10 million to abandon its claims to territory in New Mexico east of the Rio Grande.

The compromise created the illusion that the territorial issue had been resolved once and for all. “There is rejoicing over the land,” wrote one Northerner, “the bone of contention is removed; disunion, fanaticism, violence, insurrection are defeated.” Sectional hostility had been defused; calm had returned. But, as one Southern editor correctly noted, it was “the calm of preparation, and not of peace.”

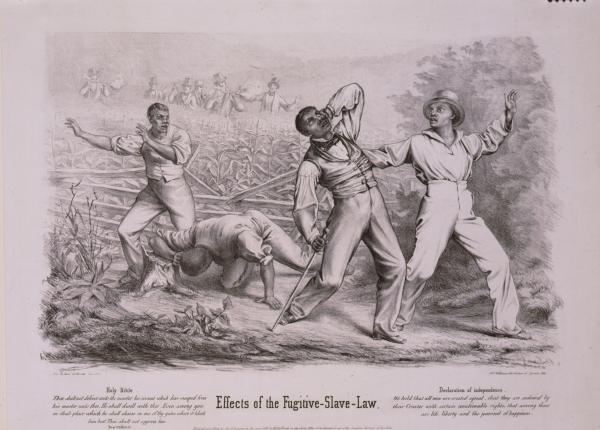

The Fugitive Slave Law

The most explosive element in the Compromise of 1850 was the Fugitive Slave Law, which required the return of runaway slaves. Any black—even free blacks—could be sent south solely on the affidavit of anyone claiming to be his or her owner. The law stripped runaway slaves of such basic legal rights as the right to a jury trial and the right to testify in one’s own defense.

Under the Fugitive Slave Law, an accused runaway was to stand trial in front of a special commissioner, not a judge or a jury, and the commissioner was to be paid $10 if a fugitive was returned to slavery but only $5 if the fugitive was freed. Many Northerners regarded this provision as a bribe to ensure that any black accused of being a runaway would be found guilty. Finally, the law required all U.S. citizens and U.S. marshals to assist in the capture of escapees. Anyone who refused to aid in the capture of a fugitive, interfered with the arrest of a slave, or tried to free a slave already in custody was subject to a heavy fine and imprisonment.

The Fugitive Slave Law produced widespread outrage in the North and convinced thousands of Northerners that slavery should be barred from the western territories. Attempts to enforce the Fugitive Slave Law provoked wholesale opposition. Eight Northern states enacted “personal liberty” laws that prohibited state officials from assisting in the return of runaways and extended the right of jury trial to fugitives. Southerners regarded these attempts to obstruct the return of runaways as a violation of the Constitution and federal law.

The free black communities of the North responded defiantly to the 1850 law. They provided fugitive slaves with sanctuary and established vigilance committees to protect blacks from hired kidnappers who were searching the North for runaways. Some 15,000 free blacks emigrated to Canada, Haiti, the British Caribbean, and Africa after the adoption of the 1850 federal law. The South’s demand for an effective fugitive slave law was a major source of sectional tension. In Christiana, Pennsylvania, in 1851, a gun battle broke out between abolitionists and slave catchers, and in Wisconsin, abolitionists freed a fugitive named Joshua Glover from a local jail. In Boston, federal marshals and 22 companies of state troops were needed to prevent a crowd from storming a court house to free a fugitive named Anthony Burns.