The Pre-Civil War South

The Pre-Civil War South

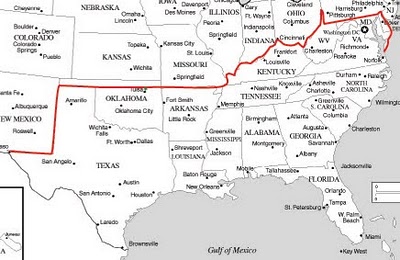

In the decades before the Civil War, Northern and Southern development followed increasingly different paths. By 1860, the North contained fifty percent more people than the South. It was more urbanized and attracted many more European immigrants. The Northern economy was more diversified into agricultural, commercial, manufacturing, financial, and transportation sectors. In contrast, the South had smaller and fewer cities and a third of its population lived in slavery. In the South, slavery impeded the development of industry and cities and discouraged technological innovation. Nevertheless, the South was wealthy, and its economy was rapidly growing. The Southern economy largely financed the Industrial Revolution in the United States, and stimulated the development of industries in the North to service Southern agriculture.

Eli Whitney & Slavery

In the early 1790s, slavery appeared to be a dying institution. Slave imports into the New World were declining and slave prices were falling because the crops grown by slaves—tobacco, rice, and indigo—did not generate enough income to pay for their upkeep.

Congress had outlawed the international slave trade and barred slavery from the Old Northwest. The Northern states had abolished slavery or instituted gradual emancipation schemes.

In Maryland and Virginia, planters were replacing tobacco, a labor-intensive crop that needed a slave labor force, with wheat and corn, which did not. At the same time, leading Southerners, including Thomas Jefferson, denounced slavery as a source of debt, economic stagnation, and moral dissipation. A French traveler reported that people throughout the South “are constantly talking of abolishing slavery, of contriving some other means of cultivating their estates.”

Then, Eli Whitney of Massachusetts gave slavery a new lease on life. In 1792 after graduating from Yale, Whitney traveled south in search of employment as a tutor. His journey was filled with disasters. During the boat trip, he became seasick. Before he could recover, his boat ran aground on rocks near New York City where he contracted smallpox. The only good thing to happen during his journey was that he was befriended by a charming Southern widow named Catharine Greene, whose late husband, General Nathanael Greene, had been a leading general during the American Revolution. When he arrived in the South, Whitney discovered that his promised salary as a tutor had been cut in half. So he quit the job and accepted Greene’s invitation to visit her plantation near Savannah, Georgia.

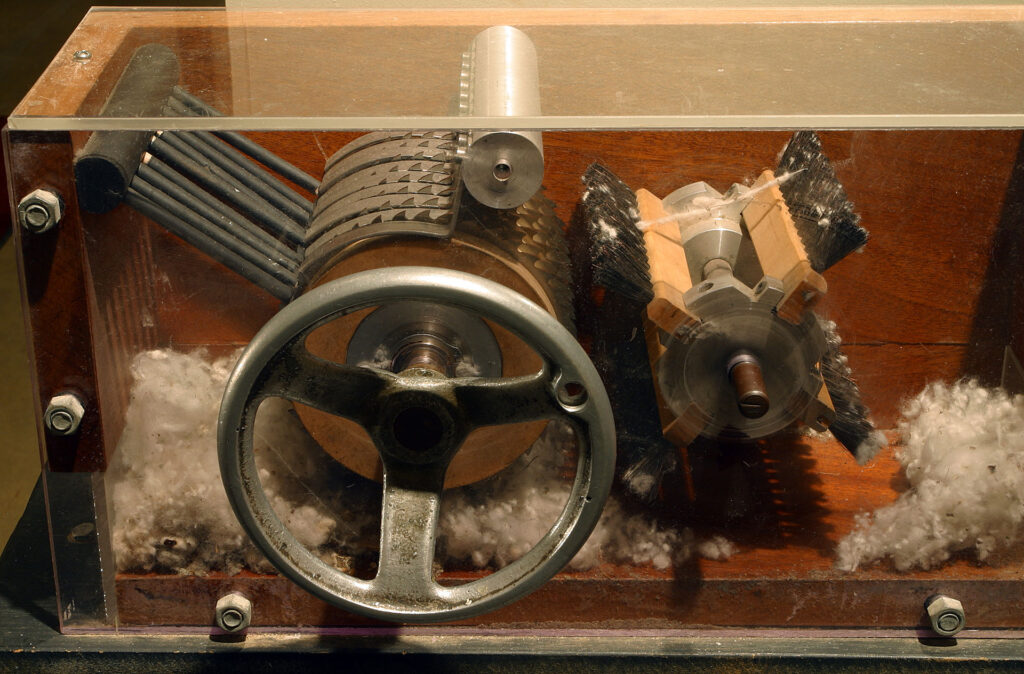

During his visit, Whitney became intrigued with the problem encountered by Southern planters in producing short-staple cotton. The booming textile industry had created a high demand for the crop, but it could not be marketed until the seeds had been extracted from the cotton boll, a laborious and time-consuming process. From a slave known only by the name Sam, Whitney learned that a comb could be used to remove seeds from cotton. In ten days, Whitney devised a way of mechanizing the comb. Within a month, Whitney’s cotton engine known as gin for short, could separate fiber from seeds faster than fifty people working by hand.

Whitney’s invention revitalized slavery in the South by stimulating demand for slaves to raise short-staple cotton. Between 1792, when Whitney arrived on the Greene plantation, and 1794, the price of slaves doubled. By 1825, field hands who brought $500 apiece in 1794, were worth $1,500. As the price of slaves rose, so too did the number of slaves. During the first decade of the nineteenth century, the number of slaves in the United States increased by thirty-three percent. During the following decade, after the African slave trade became illegal, the slave population grew another twenty-nine percent.

Historical Facts & Fiction

The Old South: Images and Realities

Pre-Civil War Americans regarded Southerners as a distinct people, who possessed their own values and ways of life. It was widely but mistakenly believed that the North and South had originally been settled by two distinct groups of immigrants, each with its own ethos. Northerners were said to be the descendants of seventeenth century English Puritans, while Southerners were the descendants of England’s country gentry.

In the eyes of many pre-Civil War Americans this contributed to the evolution of two distinct kinds of Americans: the aggressive, individualistic, money-grubbing Yankee and the Southern cavalier. According to the popular stereotype, the cavalier, unlike the Yankee, was violently sensitive to insult, indifferent to money, and preoccupied with honor.

How alike and how different were the North and South? Did the Mason-Dixon line divide the United States into two distinctive civilizations, each with its own culture and way of life?

Even today, the North and South differ in their political preferences, demographics, religion, and attitudes toward taxation, guns, corporal punishment, and other controversial matters. The legacy of the past persists.

Thinking Comparatively

How the North and South Differed

Demographic Differences

Population Size:

North: Fifty percent larger population than the South

South: Attracted far fewer immigrants.

Percentage of African Americans:

South: A third of the population was black and enslaved.

North: Less than two percent of the population was black.

Economic Differences

North: Superior in manufactures, railroad mileage, and commercial profits.

In addition to a commercial agriculture based on family farms, it had a large and growing

industrial sector based upon wage labor.

South: Deficient in industrial production, transportation, finance, and commerce.

Its economy rested on slave-based agriculture.

Power

North: Society was dominated by merchant and industrial capitalists.

South: Society was dominated by planter-slaveowners.