American Fears of Conspiracy and the Road to the Civil War

What if…

American Fears of Conspiracy & the Road to the Civil War

“Lee Harvey Oswald Didn’t Kill President John Kennedy.”

“The Moon Landing was a Hoax.”

“President Truman Ordered Cover-up of Alien Spaceship.”

“Communists Have Been Poisoning the U.S. Water Supply for 50 Years.”

Over the course of American history, waves of paranoia have swept through American society. These range from the Puritan panics over witchcraft to slave owners’ fears that their slaves were concocting murderous plots to fears of Communist subversion during the late 1940s and 1950s.

Sometimes, paranoia is rooted in reality. For example, in recent years the National Security Agency really was monitoring cell phone metadata and Internet activity. Earlier in time, the FBI did infiltrate civil rights groups and groups opposing the Vietnam War.

At other times, the fears were totally unfounded. For example, Henry Ford, the automobile manufacturer, was convinced that there was a vast Jewish conspiracy to control the world.

Fears of conspiracy are particularly likely to flourish during times of stress—during economic downturns or moments of international tension.

The important point is that fears of conspiracy and cover-ups have shaped the course of American history.

Many American Revolutionaries were convinced that the British government was plotting to strip them of their liberties. Many American policymakers during the Cold War were convinced that the Soviet Union was engaged in a plan for global domination.

Fear of conspiracy is not confined to the fringes of American society. Paranoid thinking is not limited to truthers or to deluded kooks wearing tinfoil hats to shield their brains from electromagnetic radiation, mind control, and mind reading. At various times in the past, substantial portions of the population have believed that there is a diabolical plot on the part of international bankers or munition makers (who supposedly caused World War I) or the Pope or the Masons.

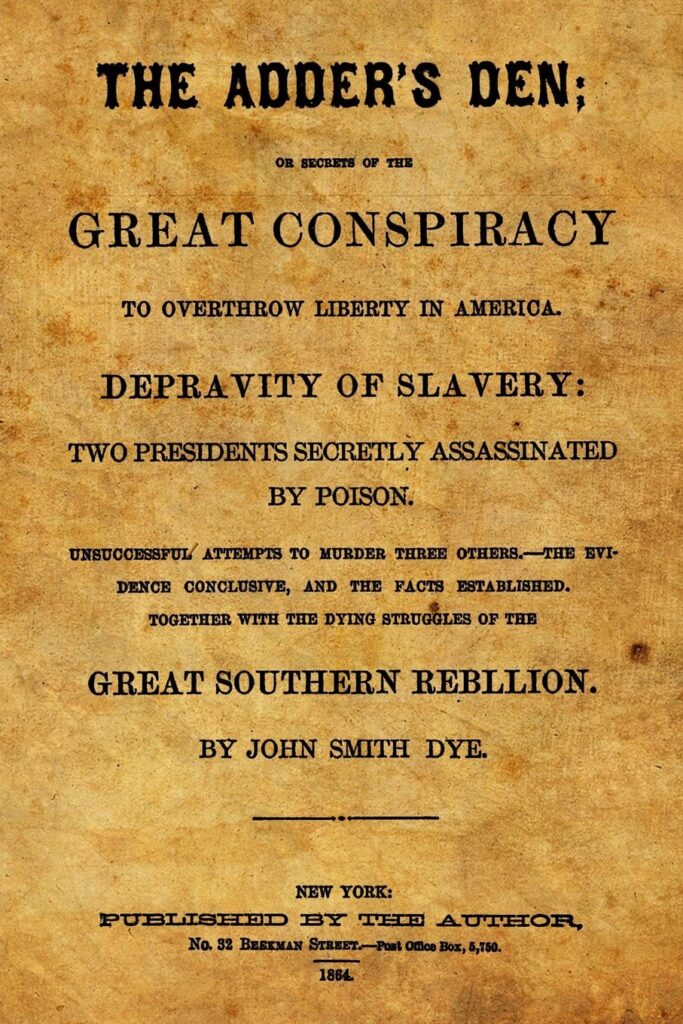

In 1864, a writer named John Smith Dye charged that for over thirty years, the South’s largest slaveowners and their political allies had engaged in a ruthless conspiracy to expand slavery.

In a book entitled, The Adder’s Den or Secrets of the Great Conspiracy to Overthrow Liberty in America, he described a deliberate, systematic plan to expand slavery into the western territories and expand the South’s slave empire. An arrogant and aggressive “Slave Power” had:

- Entrenched slavery in the Constitution;

- Caused financial panics to sabotage the Northern economy;

- Dispossessed Indians from their native lands to allow slavery to growth; and

- Fomented revolution in Texas and war with Mexico in order to expand the South’s slave empire.

Most important of all, he insisted, the Southern slaveocracy had secretly assassinated two presidents by poison and unsuccessfully attempted to murder three others.

In support of this conspiracy, Dye made the following sensational charges:

He alleged that in 1835, former Vice President John C. Calhoun, outraged by Andrew Jackson’s opposition to states’ rights and nullification, encouraged a deranged man to kill the president. The plot failed when the man’s pistols misfired.

He maintained that in 1841, agents of the Slave Power poisoned President William Henry Harrison with arsenic just thirty days after he took office, because he refused to cooperate with a Southern scheme to annex Texas. This left John Tyler, a defender of slavery as a positive good, in the White House.

In 1850, President Zachary Taylor, a Louisiana slaveowner who had commanded American troops in the Mexican war, alienated the Slave Power by opposing the extension of slavery into California. Just sixteen months after taking office, according to Dye, the Slave Power used arsenic to murder the president. He was succeeded by Vice President Millard Fillmore, who was more sympathetic to the Southern cause.

In 1853, agents of the Slave Power supposedly derailed Franklin Pierce’s railroad car while the president-elect was on the way to the presidential inauguration. The New Hampshire Democrat and his wife escaped injury, but their twelve-year-old son was killed. In the future, Pierce toed the Southern line.

On February 23, 1857, President-elect James Buchanan, a Pennsylvania Democrat, and leading politicians dined at Washington’s National Hotel. Dye charged that Southern agents sprinkled arsenic on the lump sugar used by Northerners to sweeten their tea. Because Southerners drank coffee and used granulated sugar, no Southerners were injured. But, according to Dye, sixty Northerners were poisoned, including the president, and thirty-eight died.

In fact, no credible evidence supports any of John Smith Dye’s sensational allegations.

Historians have uncovered no connection between John C. Calhoun and the assassination attempt on Andrew Jackson. Nor have researchers found any proof that Harrison’s and Taylor’s deaths resulted from poison. A 1991, a postmortem examination of Taylor’s remains found no evidence of arsenic.

There is no evidence that Southern agents derailed Pierce’s train nor is there any evidence that sixty Northerners were poisoned at the dinner for President-elect Buchanan.

Yet even if his charges were baseless, Dye was not alone in interpreting events in conspiratorial terms. His book was only one of the most extreme examples of conspiratorial charges that had been made by abolitionists since the late 1830s.

By the 1850s, a growing number of Northerners had come to believe that an aggressive Southern slave power had seized control of the federal government and threatened to subvert republican ideals of liberty, equality, and self-rule. At the same time, an increasing number of Southerners had begun to believe that antislavery radicals dominated Northern politics and would “rejoice” in the ultimate consequences of abolition-race war.