The Growth of Political Factionalism and Sectionalism

Defending American Interests in Foreign Affairs

The War of 1812 stirred a new nationalistic spirit in foreign affairs. In 1815, this spirit resulted in a decision to end the raids by the Barbary pirates on American commercial shipping in the Mediterranean. For seventeen years the United States had paid tribute to the ruler of Algiers. In March 1815, Captain Stephen Decatur and a fleet of ten ships sailed into the Mediterranean, where they captured two Algerian gunboats, towed the ships into Algiers harbor, and threatened to bombard the city. As a result, all the North African states agreed to treaties releasing American prisoners without ransom, ending all demands for American tribute, and providing compensation for American vessels that had been seized.

After successfully defending American interests in North Africa, Monroe acted to settle old grievances with the British. Britain and the United States had left a host of issues unresolved in the peace treaty ending the War of 1812, including disputes over boundaries, trading and fishing rights, and rival claims to the Oregon region of the Pacific Northwest. The two governments moved quickly to settle these issues. The Rush-Bagot Agreement (1817) removed most military ships from the Great Lakes. In 1818, Britain granted American fishermen the right to fish in eastern Canadian waters, agreed to the 49th parallel as the boundary between the United States and Canada from Minnesota to the Rocky Mountains, and consented to joint occupation of the Oregon region.

The critical foreign policy issue facing the United States after the War of 1812 was the fate of Spain’s crumbling New World empire. Many of Spain’s New World colonies had taken advantage of turmoil in Europe during the Napoleonic Wars to fight for their independence. These revolutions aroused intense sympathy in the United States, but many Americans feared that European powers might restore monarchical order in Spain’s New World.

A source of particular concern was Florida, which was still under Spanish control. Pirates, fugitive slaves, and Native Americans used Florida as a sanctuary and as a jumping off point for raids on settlements in Georgia. In December 1817, to end these incursions, Monroe authorized General Andrew Jackson to lead a punitive expedition against the Seminole Indians in Florida. Jackson attacked the Seminoles, destroyed their villages, and overthrew the Spanish governor. He also court-martialed and executed two British citizens whom he accused of inciting the Seminoles to commit atrocities against Americans.

Jackson’s actions provoked a furor in Washington. Spain protested Jackson’s acts and demanded that he be punished. Secretary of War John C. Calhoun and other members of Monroe’s cabinet urged the resident to reprimand Jackson for acting without specific authorization. In Congress, Henry Clay called for Jackson’s censure. Secretary of State Adams, however, saw in Jackson’s actions an opportunity to wrest Florida from Spain.

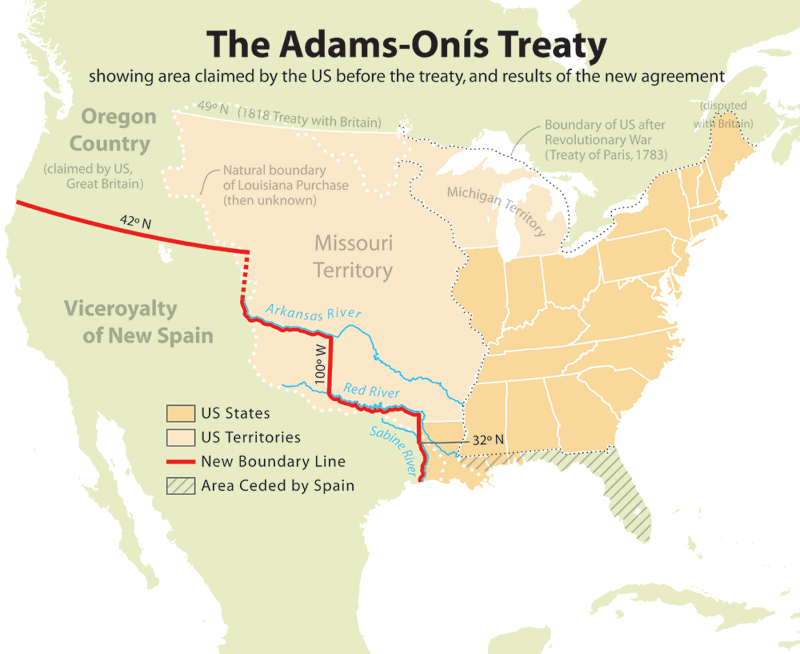

Instead of apologizing for Jackson’s conduct, Adams declared that the Florida raid was a legitimate act. Adams informed the Spanish government that it would either have to police Florida effectively or cede it to the United States. Convinced that American annexation was inevitable, Spain ceded Florida to the United States in the Adams-Onis Treaty of 1819. In return, the United States agreed to honor $5 million in damage claims by Americans against Spain. Under the treaty, Spain relinquished its claims to Oregon and the United States renounced, at least temporarily, its claims to Texas.

At the same time, European intervention in the Pacific Northwest and Latin America threatened to become a new source of anxiety for American leaders. In 1821, Russia claimed control of the entire Pacific coast from Alaska to Oregon and closed the area to foreign shipping. This development coincided with rumors that Spain, with the help of its European allies, was planning to reconquer its former colonies in Latin America. European intervention threatened British as well as American interests. Not only did Britain have a flourishing trade with Latin America, which would decline if Spain regained its New World colonies, but it also occupied the Oregon region jointly with the United States. In 1823, British Foreign Minister George Canning proposed that the United States and Britain jointly announce their opposition to further European intervention in the Americas.

Monroe initially regarded the British proposal favorably. But his secretary of state, John Quincy Adams, opposed a joint Anglo-American declaration. Secure in the knowledge that the British would use their fleet to support the American position, Adams convinced President Monroe to make an independent declaration of American policy. In his annual message to Congress in 1823, Monroe outlined the principles that have become known as the Monroe Doctrine. He announced that the Western Hemisphere was henceforth closed to any further European colonization, declaring that the United States would regard any attempt by European nations “to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety.” European countries with possessions in the hemisphere—Britain, France, the Netherlands, and Spain—were warned not to attempt expansion. Monroe also said that the United States would not interfere in internal European affairs.

For the American people, the Monroe Doctrine was the proud symbol of American hegemony in the Western Hemisphere. Unilaterally, the United States had defined its rights and interests in the New World. It is true that during the first half of the nineteenth century the United States lacked the military power to enforce the Monroe Doctrine and depended on the British navy to deter European intervention in the Americas, but the nation had clearly warned the European powers that any threat to American security would provoke American retaliation.

The Era of Good Feelings marked one of the most successful periods in American diplomacy. Apart from ending the attacks of the Barbary pirates on American shipping, the United States settled many of its disagreements with Britain, acquired Florida from Spain, defined its western and southwestern boundaries, convinced Spain to relinquish its claims to the Oregon region, and delivered a strong warning that European powers were not to interfere in the Western Hemisphere

Podcast

America’s First Hostage Crisis

Listen to “America’s First Hostage Crisis.”

The Growth of Political Factionalism and Sectionalism

The Era of Good Feelings began with a burst of nationalistic fervor. The economic program adopted by Congress, including a national bank and a protective tariff, reflected the growing feeling of national unity. The Supreme Court promoted the spirit of nationalism by establishing the principle of federal supremacy. Industrialization and improvements in transportation also added to the sense of national unity by contributing to the nation’s economic strength and independence and by linking the West and the East together.

But this same period also witnessed the emergence of growing factional divisions in politics, including a deepening sectional split between the North and South. A severe economic depression between 1819 and 1822 provoked bitter division over questions of banking and tariffs. Geographic expansion exposed latent tensions over the morality of slavery and the balance of economic power. It was during the Era of Good Feelings that the political issues arose that would dominate American politics for the next forty years.

The Panic of 1819

In 1819, a financial panic swept across the country. The growth in trade that followed the War of 1812 came to an abrupt halt. Unemployment mounted, banks failed, mortgages were foreclosed, and agricultural prices fell by half. Investment in western lands collapsed.

The panic was frightening in its scope and impact. In New York State, property values fell from $315 million in 1818 to $256 million in 1820. In Richmond, property values fell by half. In Pennsylvania, land values plunged from $150 an acre in 1815 to $35 in 1819. In Philadelphia, 1,808 individuals were committed to debtors’ prison. In Boston, the figure was 3,500.

For the first time in American history, the problem of urban poverty commanded public attention. In New York in 1819, the Society for the Prevention of Pauperism counted 8,000 paupers out of a population of 120,000. The next year, the figure climbed to 13,000. Fifty thousand people were unemployed or irregularly employed in New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. One foreign observer estimated that half a million people were jobless nationwide. To address the problem of destitution, newspapers appealed for old clothes and shoes for the poor, and churches and municipal governments distributed soup. Baltimore set up twelve soup kitchens in 1820 to give food to the poor.

The downswing spread like a plague across the country. In Cincinnati, bankruptcy sales occurred almost daily. In Lexington, Kentucky, factories worth half a million dollars were idle. Matthew Carey, a Philadelphia economist, estimated that three million people, one-third of the nation’s population, were adversely affected by the panic. In 1820, John C. Calhoun commented: “There has been within these two years an immense revolution of fortunes in every part of the Union; enormous numbers of persons utterly ruined; multitudes in deep distress.”

The panic had several causes, including a dramatic decline in cotton prices, a contraction of credit by the Bank of the United States designed to curb inflation, an 1817 congressional order requiring hard-currency payments for land purchases, and the closing of many factories due to foreign competition.

The panic unleashed a storm of popular protest. Many debtors agitated for “stay laws” to provide relief from debts as well as the abolition of debtors’ prisons. Manufacturing interests called for increased protection from foreign imports, but a growing number of southerners believed that high protective tariffs, which raised the cost of imported goods and reduced the flow of international trade, were the root of their troubles. Many people clamored for a reduction in the cost of government and pressed for sharp reductions in federal and state budgets. Others, particularly in the South and West, blamed the panic on the nation’s banks and particularly the tight-money policies of the Bank of the United States.

By 1823 the panic was over. But it left a lasting imprint on American politics. The panic led to demands for the democratization of state constitutions, an end to restrictions on voting and office holding, and heightened hostility toward banks and other “privileged” corporations and monopolies. The panic also exacerbated tensions within the Republican Party and aggravated sectional tensions as Northerners pressed for higher tariffs while Southerners abandoned their support of nationalistic economic programs.

The Missouri Crisis

In the midst of the panic, a crisis over slavery erupted with stunning suddenness. It was, Thomas Jefferson who wrote, like “a firebell in the night.” The crisis was ignited by the application of Missouri for statehood, and it involved the status of slavery west of the Mississippi River.

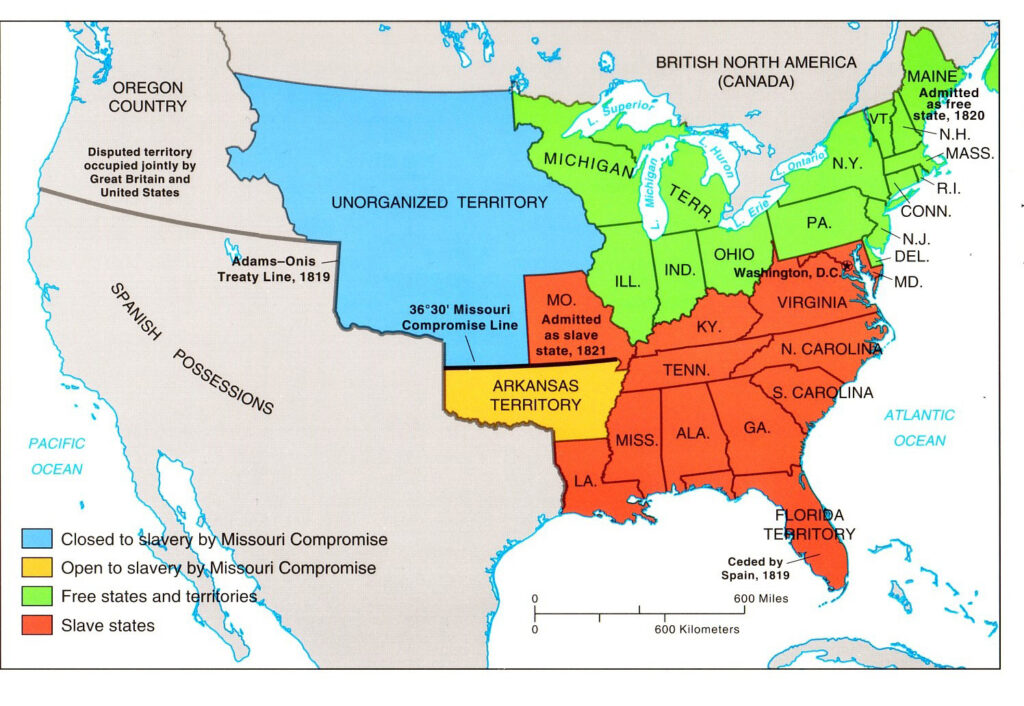

East of the Mississippi, the Mason-Dixon line and the Ohio River formed a boundary between the North and South. States south of this line were slave states; states north of this line had either abolished slavery or adopted gradual emancipation policies. West of the Mississippi, however, no clear line demarcated the boundary between free and slave territory.

Representative James Tallmadge, a New York Republican, provoked the crisis in February 1819 by introducing an amendment to restrict slavery in Missouri as a condition of statehood. The amendment prohibited the further introduction of slaves into Missouri and provided for emancipation of all children of slaves at the age of twenty-five. Voting along ominously sectional lines, the House approved the Tallmadge Amendment, but the amendment was defeated in the Senate.

Southern and Northern politicians alike responded with fury. Southerners condemned the Tallmadge proposal as part of a Northeastern plot to dominate the government. They declared the United States to be a union of equals, claiming that Congress had no power to place special restrictions upon a state. John Randolph declared that “God has given us Missouri and the devil shall not take it from us.”

Talk of disunion and civil war was rife. Senator Freeman Walker of Georgia envisioned “civil war … a brother’s sword crimsoned with a brother’s blood.” Northern politicians responded with equal vehemence. Said Representative Tallmadge, “If blood is necessary to extinguish any fire which I have assisted to kindle, I can assure you gentlemen, while I regret the necessity, I shall not forbear to contribute my mite.” Northern leaders argued that national policy, enshrined in the Northwest Ordinance, committed the government to halt the expansion of the institution of slavery. They warned that the extension of slavery into the West would inevitably increase the pressures to reopen the African slave trade.

This was not the first congressional crisis over slavery. In 1790, a bitter dispute had arisen over whether Congress should accept antislavery petitions. In 1798, a furor had erupted over a proposal to extend the Northwest Ordinance prohibition on slavery to Mississippi. In 1804, a new uproar had broken out over a proposal to ban new slaves from immigrating to Louisiana. In 1801 and again in 1814-1815, Federalists had protested the Three-fifths Compromise, but never before had passions been so heated or sectional antagonisms so overt.

In the Northeast, for the first time, philanthropists like Elias Boudinot of Burlington, New Jersey, succeeded in mobilizing public opinion against the westward expansion of slavery. Mass meetings convened in a number of cities in the Northeast. The vehemence of anti-Missouri feeling is apparent in an editorial that appeared in the New York Advertiser: “THIS QUESTION INVOLVES NOT ONLY THE FUTURE CHARACTER OF OUR NATION, BUT THE FUTURE WEIGHT AND INFLUENCE OF THE FREE STATES. IF NOW LOST—IT IS LOST FOREVER.”

Compromise ultimately resolved the crisis of 1819. The Senate narrowly voted to admit Missouri as a slave state. To preserve the sectional balance, it also voted to admit Maine, which had previously been a part of Massachusetts, as a free state, and to prohibit the formation of any further slave states from the territory of the Louisiana Purchase north of the 36 degrees 30 minutes north latitude. Henry Clay then skillfully steered the compromise through the House, where a handful of antislavery representatives, fearful of the threat to the Union, threw their support behind the proposals.

A second crisis erupted when the Missouri constitutional convention directed the state legislature to forbid the migration of free blacks and mulattoes into the state. This crisis, too, was resolved by compromise. Missouri agreed not to abridge the constitutional rights of any United States citizens—without specifically acknowledging that free blacks were U.S. citizens.

Compromise was possible in 1819 and 1820 because most Northerners were apathetic to the Tallmadge Amendment and opponents of slavery were still disunited. Public attention was focused on the Panic of 1819 and the resulting depression. Leadership of the drive to restrict slavery in Missouri had been assumed by Presbyterian and Congregationalist churchmen, provoking widespread hostility from an anticlerical and anti-Federalist opposition.

Southerners won a victory in 1820, but they paid a high price. While many states would eventually be organized from the Louisiana Purchase area north of the compromise line, only two (Arkansas and part of Oklahoma) would be formed from the southern portion. If the South was to defend its political power against an antislavery majority, it had but two options in the future. It would either have to forge new political alliances with the North and West, or it would have to acquire new territory in the Southwest. The latter would inevitably reignite Northern opposition to the further expansion of slavery.

The Era of Good Feelings ended on a note of foreboding. Although compromise had been achieved, it was clear that sectional conflict had not been resolved, only postponed. Sectional antagonism, Jefferson wrote, “is hushed, indeed, for the moment. But this is a reprieve only, not a final sentence. A geographical line, coinciding with a marked principle, moral and political, once conceived and held up to the angry passions of men, will never be obliterated; and every new irritation will mark it deeper and deeper.” John Quincy Adams agreed. The Missouri crisis, he wrote, is only the “title page to a great tragic volume.”