The Era of Good Feelings

The Era of Good Feelings

he Era of Good Feelings was a period of dramatic growth and intense nationalism. The spirit of nationalism was apparent in Supreme Court decisions that established the supremacy of the federal government and expanded the powers of Congress. American interest and power in foreign policy was especially apparent in the Monroe Doctrine. Industrial development enhanced national self-sufficiency and united the nation with improved roads, canals, and river transportation.

Forces for division were also at work. The financial panic of 1819 led to the emergence of new political parties. The Missouri Crisis contributed to a growing sectional split between North and South.

The Growth of American Nationalism

Early in the summer of 1817, as a conciliatory gesture toward the Federalists who had opposed the War of 1812, James Monroe, the nation’s fifth president, embarked on a goodwill tour through the North. Everywhere Monroe went, citizens greeted him warmly, holding parades and banquets in his honor. In Federalist Boston, a crowd of 40,000 welcomed the Republican president. John Quincy Adams expressed amazement at the acclaim with which the president was greeted: “Party spirit has indeed subsided throughout the Union to a degree that I should have thought scarcely possible.”

A Federalist newspaper, reflecting on the end of party warfare and the renewal of national unity, called the times the “Era of Good Feelings.” The phrase accurately describes the period of James Monroe’s presidency, which, at least in its early years, was marked by a relative absence of political strife and opposition. With the collapse of the Federalist Party, the Jeffersonian Republicans dominated national politics. Reflecting a new spirit of political unity, the Republicans adopted many of the nationalistic policies of their former opponents, establishing a second national bank, a protective tariff, and improvements in transportation.

The spirit of nationalism was also apparent in a series of landmark Supreme Court decisions that established national supremacy over the states and in a series of foreign policy triumphs that extended the nation’s boundaries and protected its shipping and commerce.

To the American people, James Monroe was the popular symbol of the Era of Good Feelings. His life embodied much of the history of the young republic. He had joined the Revolutionary Army in 1776 and had spent the terrible winter of 1777-1778 at Valley Forge. He had been a member of the Confederation Congress and served as minister to both France and Great Britain. During the War of 1812, he had performed double duty as Secretary of State and Secretary of War. With the Federalist Party in a state of collapse, he had been easily elected president, carrying all but three states.

A dignified and formal man, Monroe was the last president to don the fashions of the eighteenth century. He wore his hair in a powdered wig tied in a queue and dressed himself in a cocked hat, a black broadcloth tailcoat, knee breeches, long white stockings, and buckled shoes. His political values, too, were those of an earlier day. Like George Washington, Monroe worked to eliminate party and sectional rivalries by his attitudes and behavior. He hoped for a country without political parties, governed by leaders chosen on their merits. Anxious to unite all sections of the country, he tried to appoint a representative of each section to his cabinet and named John Quincy Adams, a former Federalist and son of a Federalist president, as secretary of state. So great was his popularity that he won a second presidential term by an Electoral College vote of 231 to 1. A new era of national unity appeared to have dawned.

Shifting Political Values

Traditionally, the Republican Party stood for limited government, states’ rights, and a strict interpretation of the Constitution. By 1815, however, the party had adopted former Federalist positions on a national bank, protective tariffs, a standing army, and national roads.

In a series of policy recommendations to Congress at the end of the War of 1812, President Madison revealed the extent to which Republicans had adopted Federalist policies. He called for a program of national economic development directed by the central government, which included creation of a second Bank of the United States to provide for a stable currency, a protective tariff to encourage industry, a program of internal improvements to facilitate transportation, and a permanent 20,000-man army. In subsequent messages, he recommended an extensive system of roads and canals, new military academies, and establishment of a national university in Washington.

Old-style Republicans, who clung to the Jeffersonian ideal of limited government, dismissed Madison’s proposals as nothing but “old Federalism, vamped up into something bearing the superficial appearance of Republicanism.” But Madison’s program found enthusiastic support among the new generation of political leaders. Convinced that inadequate roads, the lack of a national bank, and dependence on foreign imports had nearly resulted in a British victory in the war, these young leaders were eager to use the federal government to promote national economic development.

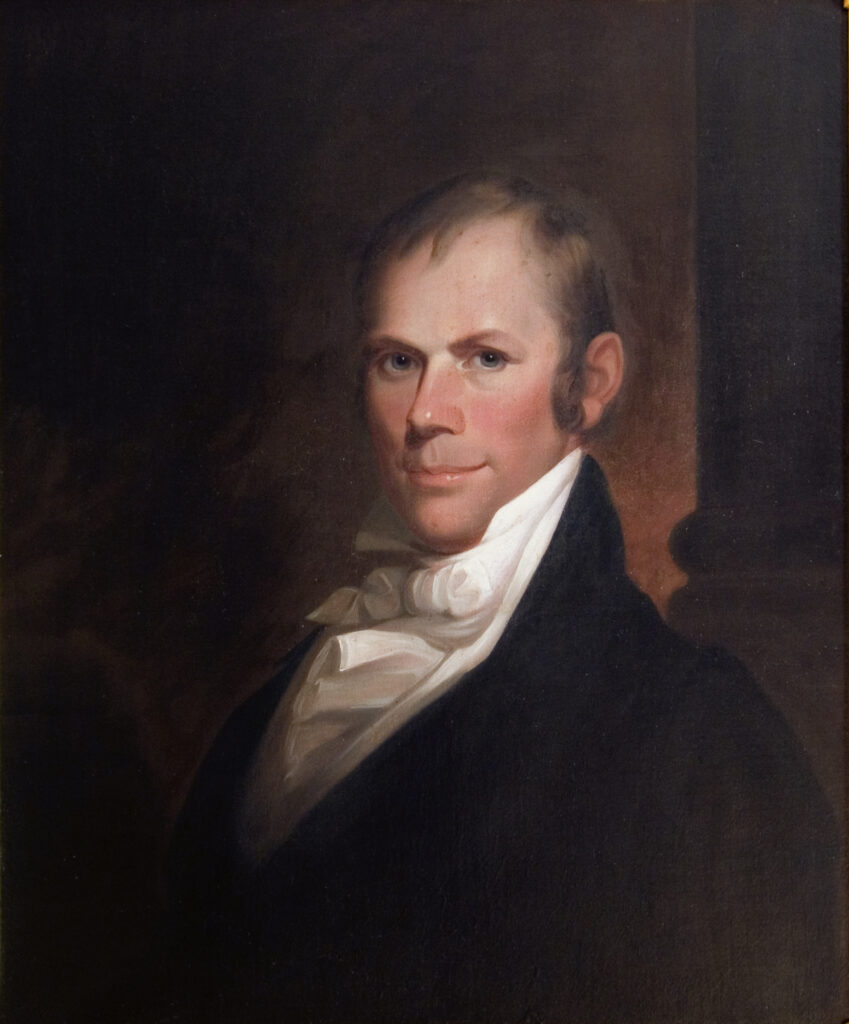

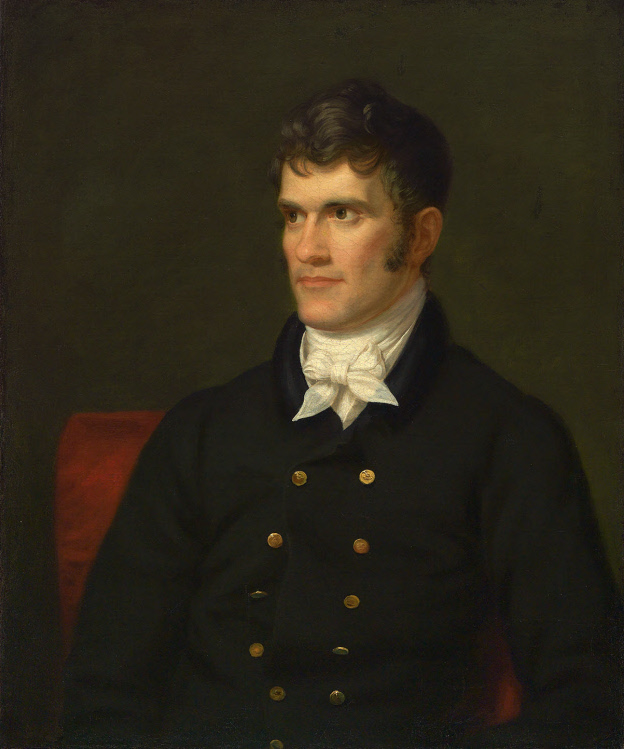

Henry Clay, John C. Calhoun, and Daniel Webster were the preeminent leaders of the second generation of American political life—the period stretching from the War of 1812 to almost the eve of the Civil War. All shared similar backgrounds. Each was born on a poor or modest farm. Each became a lawyer. Each arrived in Washington, D.C., around the beginning of the War of 1812 and became the preeminent spokesman of his region—Clay of the West, Calhoun of the South, Webster of the North. Each possessed extraordinary oratorical talent. Each served in the cabinet as secretary of state or secretary of war. They died within a few months of each other in the early 1850s.

The leader of this group of younger politicians was Henry Clay, a Republican from Kentucky. Named Speaker on his very first day in the House of Representatives in 1811, Clay was one of the “War Hawks” who had urged President Madison to wage war against Britain. After the war, Clay became one of the strongest proponents of an active federal role in national economic development. He used his position as Speaker of the House to advance an economic program that he later called the “American System.” According to this plan, the federal government would erect a high protective tariff to keep out foreign goods, stimulate the growth of industry, and create a large urban market for Western and Southern farmers. Revenue from the tariff, in turn, would be used to finance internal improvements of roads and canals to stimulate the growth of the South and West.

Another leader of postwar nationalism was John C. Calhoun, a Republican from South Carolina. Calhoun, like Clay, entered Congress in 1811, and later served with distinction as Secretary of War under Monroe and as Vice President under both John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson. Later, Calhoun became the nation’s leading exponent of states’ rights, but at this point he seemed to John Quincy Adams, “above all sectional and factious prejudices more than any other statesman of this Union with whom I have ever acted.”

The other dominant political figure of the era was Daniel Webster. Nicknamed “Black Dan” for his dark hair and eyebrows, and “the Godlike Daniel” for his magnificent speaking style, Webster argued 168 cases before the Supreme Court. When he entered Congress as a Massachusetts Federalist, he opposed the War of 1812, the creation of a second national bank, and a protectionist tariff. But, later in his career, after industrial interests supplanted shipping and importing interests in the Northeast, Webster became a staunch defender of the national bank and a high tariff, and perhaps the nation’s strongest exponent of nationalism and strongest critic of states’ rights. He would insist that the United States was not only a union of states but a union of people. His words—that the United States was a “people’s government, made for the people, by the people, and answerable to the people”—would later be seized on by Abraham Lincoln.

Strengthening American Finances

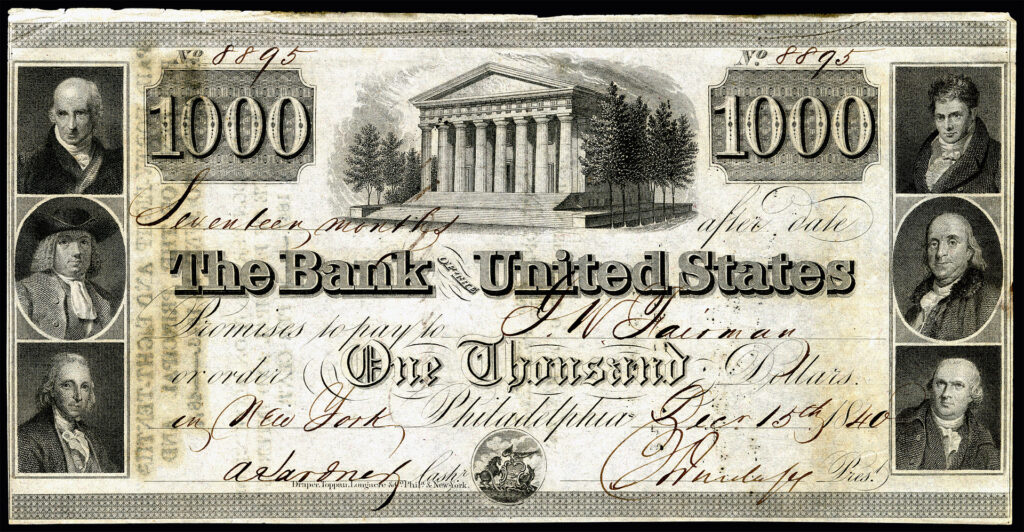

The severe financial problems created by the War of 1812 led to a wave of support for the creation of a second national bank. The demise of the first Bank of the United States just before the war had left the nation ill-equipped to deal with the war’s financial demands. To finance the war effort, the government borrowed from private banks at high interest rates. As demand for credit rose, the private banks issued bank notes greatly exceeding the amount of gold or silver that they held. One Rhode Island bank issued $580,000 in notes backed up by only $86.48 in gold and silver. The result was high inflation. Prices jumped forty percent in just two years.

To make matters worse, the United States government was unable to redeem millions of dollars deposited in private banks. In 1814, after the British burned the nation’s capital, many banks outside of New England stopped redeeming their notes in gold or silver. Soldiers, army contractors, and government securities holders went unpaid, and the Treasury temporarily went bankrupt. After the war was over, many banks still refused to resume payments in gold or silver.

In 1816, Congress voted by a narrow margin to charter a second Bank of the United States for twenty years and give it the privilege of holding government funds without paying interest for their use. In return, it required the bank to pay a bonus of $1.5 million to the federal government and let the president name five of the bank’s twenty-five directors. Supporters of a second national bank argued that it would provide a safe place to deposit government funds and a convenient mechanism for transferring money between states. Supporters also claimed that a national bank would promote monetary stability by regulating private banks. A national bank would strengthen the banking system by refusing to accept the notes issued by overspeculative private banks and ensuring that bank notes were readily exchangeable for gold or silver. Opposition to a national bank came largely from private banking interests and traditional Jeffersonians, who considered a national bank to be unconstitutional and a threat to republican government.

Protecting American Industry

The War of 1812 provided tremendous stimulus to American manufacturing. It encouraged American manufacturers to produce goods previously imported from overseas. By 1816, 100,000 factory workers, two-thirds of them women and children, produced more than $40 million worth of manufactured goods a year. Capital investment in textile manufacturing, sugar refining, and other industries totaled $100 million.

Following the war, however, cheap British imports flooded the nation, threatening to undermine local industries. In Parliament, a British minister defended the practice of dumping goods at prices below their actual cost on grounds that outraged Americans. “It is well worth while,” the minister declared, “to incur a loss upon the first exportation, in order, by a glut, to stifle in the cradle those rising manufacturers in the United States which the war had forced into existence.” So severe was the perceived threat to the nation’s economic independence that Thomas Jefferson, who had once denounced manufacturing as a menace to the nation’s republican values, spoke out in favor of protecting manufacturing industries: “We must now place the manufacturer by the side of the agriculturalist.”

Congress responded to the flood of imports by continuing a tariff set during the War of 1812 to protect America’s infant industries from low-cost competition. With import duties ranging from fifteen to thirty percent on cotton, textiles, leather, paper, pig iron, wool, and other goods, the tariff promised to protect America’s growing industries from foreign competition. Shipping and farming interests opposed the tariff on the grounds that it would make foreign goods more expensive to buy and would provoke foreign retaliation.

Judicial Nationalism

The decisions of the Supreme Court also reflected the nationalism of the postwar period. With John Marshall as chief justice, the Supreme Court greatly expanded its powers, prestige, and independence. When Marshall took office, in the last days of John Adams’s administration in 1801, the Court met in the basement of the Capitol and was rarely in session for more than six weeks a year. Since its creation in 1789, the Court had only decided one hundred cases.

In a series of critical decisions, the Supreme Court greatly expanded its authority. Marbury v. Madison (1803) established the Supreme Court as the final arbiter of the Constitution and its power to declare acts of Congress unconstitutional. Fletcher v. Peck (1810) declared the Court’s power to void state laws. Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee (1816) gave the Court the power to review decisions by state courts.

After the War of 1812, Marshall wrote a series of decisions that further strengthened the powers of the national government. McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) established the constitutionality of the second Bank of the United States and denied to states the right to exert independent checks on federal authority. The case involved a direct attack on the second Bank of the United States by the state of Maryland, which had placed a tax on the bank notes of all banks not chartered by the state.

In his decision, Marshall dealt with two fundamental questions. The first was whether the federal government had the power to incorporate a bank. The answer to this question, the Court ruled, was yes because the Constitution granted Congress implied powers to do whatever was “necessary and proper” to carry out its constitutional powers—in this case, the power to manage a currency. In a classic statement of “broad” or “loose” construction of the Constitution, Marshall said, “Let the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of the Constitution, and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end, which are not prohibited, but consistent with the letter and spirit of the Constitution, are constitutional.”

The second question raised in McCullouch v. Maryland was whether a state had the power to tax a branch of the Bank of the United States. In answer to this question, the Court said no. The Constitution, the Court asserted, created a new government with sovereign power over the states. “The power to tax involves the power to destroy,” the Court declared, and the states do not have the right to exert an independent check on the authority of the federal government.

During this period, the Supreme Court also encouraged economic competition and development. In Dartmouth v. Woodward (1819) the Court promoted business growth by denying states the right to alter or impair contracts unilaterally. The case involved the efforts of the New Hampshire legislature to alter the charter of Dartmouth College, which had been granted by George III in 1769. The Court held that a charter was a valid contract protected by the Constitution and that states do not have the power to alter contracts unilaterally.

In Gibbons v. Ogden (1824), the Court broadened federal power over interstate commerce. The Court overturned a New York law that had awarded a monopoly over steamboat traffic on the Hudson River, ruling that the Constitution had specifically given Congress the power to regulate commerce.

Under John Marshall, the Supreme Court established a distribution of constitutional powers that the country still follows. The Court became the final arbiter of the constitutionality of federal and state laws, and the federal government exercised sovereign power over the states. As a result of these decisions, it would become increasingly difficult in the future to argue that the union was a creation of the states, that states could exert an independent check on federal government authority, or that Congress’s powers were limited to those specifically conferred by the Constitution.

Conquering Space

Prior to 1812, westward expansion had proceeded slowly. Most Americans were nestled along the Atlantic coastline. More than two-thirds of the new nation’s population still lived within fifty miles of the Atlantic seaboard, and the center of population rested within eighteen miles of Baltimore. Only two roads cut across the Allegheny Mountains, and no more than half a million pioneers had moved as far west as Kentucky, Tennessee, Ohio, or the western portion of Pennsylvania. Cincinnati was a town of 15,000 people; Buffalo and Rochester, New York, did not yet exist. Kickapoos, Miamis, Wyandots, and other Indian peoples populated the areas that would become the states of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, and Wisconsin, while Cherokees, Chickasaws, Choctaws, and Creeks considered the future states of Alabama, Mississippi, and western Georgia their territory.

Between 1803, when Ohio was admitted to the Union, and the beginning of the War of 1812, not a single new state was carved out of the West. Thomas Jefferson estimated in 1803 that it would be a thousand years before settlers occupied the region east of the Mississippi.

The end of the War of 1812 unleashed a rush of pioneers to Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, northern Georgia, western North Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Tennessee. Congress quickly admitted five states to the Union: Louisiana in 1812, Indiana in 1816, Mississippi in 1817, Illinois in 1818, and Alabama in 1819.

Farmers demanded that Congress revise legislation to make it easier to obtain land. Originally, Congress viewed federal lands as a source of revenue, and public land policies reflected that view. Under a policy adopted in 1785 and reaffirmed in 1796, the federal government only sold land in blocks of at least 640 acres. Although the minimum allotment was reduced to 320 acres in 1800, federal land policy continued to retard sales and concentrate ownership in the hands of a few large land companies and wealth speculators.

In 1820, Congress sought to make it easier for farmers to purchase homesteads in the West by selling land in small lots suitable for operation by a family. Congress reduced the minimum allotment offered for sale from 320 to 80 acres. The minimum price per acre fell from $2 to $1.25. In 1796, a pioneer farmer purchasing a western farm from a federal land office had to buy 640 acres costing $1280. In 1820, a farmer could purchase 80 acres for just $100. The second Bank of the United States encouraged land purchases by liberally extending credit. The result was a boom in land sales. For a decade, the government sold approximately a million acres of land annually.

Westward expansion also created a demand to expand and improve the nation’s roads and canals. In 1808, Albert Gallatin, Thomas Jefferson’s Treasury Secretary, proposed a $20 million program of canal and road construction. As a result of state and sectional jealousies and charges that federal aid to transportation was unconstitutional, the federal government funded only a single turnpike, the National Road, at this time stretching from Cumberland, Maryland, to Wheeling, Virginia (later West Virginia), but much later extending westward from Baltimore through Ohio and Indiana to Vandalia, Illinois.

In 1816, John C. Calhoun introduced a new proposal for federal aid for road and canal construction. Failure to link the nation together with an adequate system of transportation would, Calhoun warned, lead “to the greatest of calamities—disunion.” “Let us,” he exclaimed, “bind the republic together with a perfect system of roads and canals. Let us conquer space.” Narrowly, Calhoun’s proposal passed. But on the day before he left office, Madison vetoed the bill on constitutional grounds.

Despite this setback, Congress did adopt major parts of the nationalist neo-Hamiltonian economic program. It had established a second Bank of the United States to provide a stable means of issuing money and a safe depository for federal funds. It had enacted a tariff to raise duties on foreign imports and guard American industries from low-cost competition. It had also instituted a new public land policy to encourage western settlement. In short, Congress had translated the spirit of national pride and unity that the nation felt after the War of 1812 into a legislative program that placed the national interest above narrow sectional interests.