The War of 1812

The Eagle, the Tiger, and the Shark

In 1804, Jefferson was easily re-elected, carrying every state except Connecticut and Delaware. His second term began, he later wrote, “without a cloud on the horizon.” But storm clouds soon gathered as a result of war between Britain and France.

In May 1803, just two weeks after Napoleon sold Louisiana to the United States, France declared war on Britain. The war lasted twelve years. In 1805, France defeated the armies of Austria and Russia and gained control of much of continental Europe. Napoleon then massed his troops for an invasion of England. But at the battle of Trafalgar off the Spanish coast, the British fleet captured 14,000 French and Spanish sailors. Britain was now master of the seas, but France remained supreme on the land.

As part of his overall strategy to bring Britain to its knees, Napoleon closed European ports to British goods and ordered the seizure of any vessel that carried British goods or stopped in a British port. Britain retaliated in 1807 by issuing Orders in Council, which required all ships to land at a British port to obtain a license and pay a tariff. United States shipping was caught in the crossfire. France seized 500 ships and Britain nearly 1,000.

The most outrageous violation of America’s rights was the British practice of impressment. The British navy desperately needed sailors. Unable to get enough volunteers, the British navy seized men on streets and in taverns. When these efforts failed to muster sufficient men, the British began to stop foreign ships and remove seamen alleged to be British subjects. By 1811, nearly 10,000 American sailors had been forced into the British navy. Some were actually deserters from British ships who made more money sailing on U.S. ships.

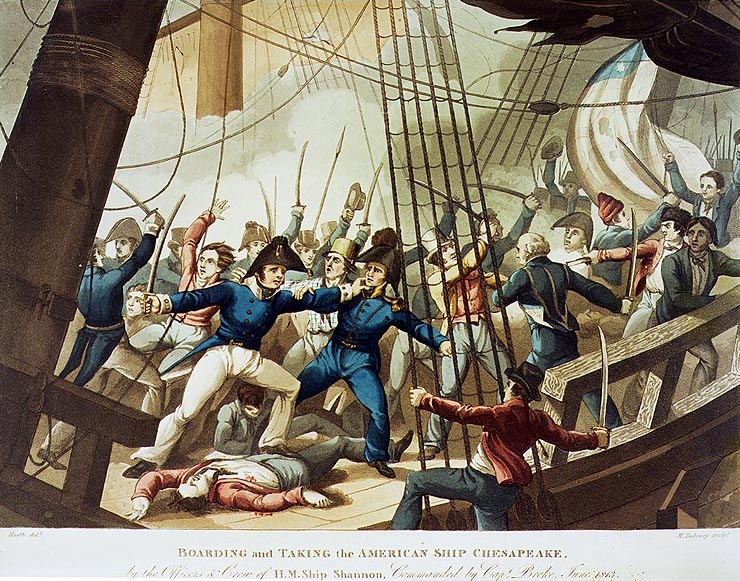

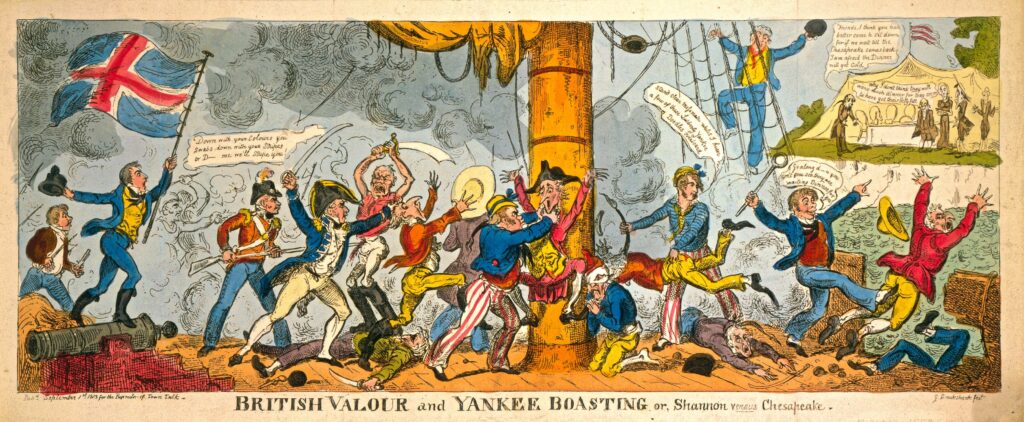

Outrage over impressment reached a fever pitch in 1807 when the British man-of-war Leopard fired at the American naval frigate, USS Chesapeake, killing three American sailors. British authorities then boarded the American ship and removed four sailors, only one of whom was really a British subject.

The Embargo of 1807

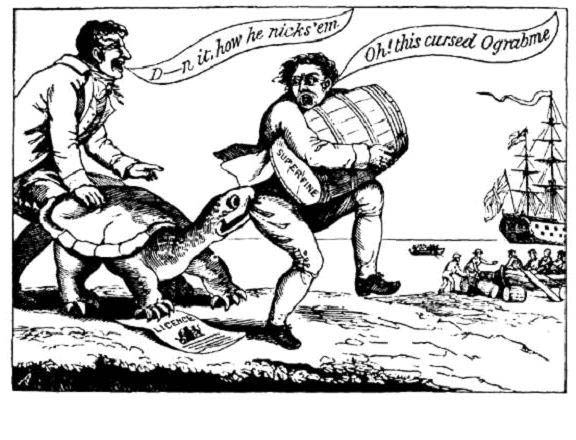

In a desperate attempt to avert war, the United States imposed an embargo on foreign trade. Jefferson regarded the embargo as an idealistic experiment—a moral alternative to war. He believed that economic coercion would convince Britain and France to respect America’s neutral rights.

The embargo was an unpopular and costly failure. It hurt the American economy far more than the British or French, and resulted in widespread smuggling. Exports fell from $108 million in 1807 to just $22 million in 1808. Farm prices fell sharply. Shippers also suffered. Harbors filled with idle ships and nearly 30,000 sailors found themselves jobless.

Jefferson believed that Americans would cooperate with the embargo out of a sense of patriotism. Instead, smuggling flourished, particularly through Canada. To enforce the embargo, Jefferson took steps that infringed on his most cherished principles: individual liberties and opposition to a strong central government. He mobilized the army and navy to enforce the blockade, and declared the Lake Champlain region of New York, along the Canadian border, in a state of insurrection.

Pressure to abandon the embargo mounted, and early in 1809, just three days before Jefferson left office, Congress repealed the embargo. In effect for fifteen months, the embargo exacted no political concessions from either France or Britain. But it had produced economic hardship, evasion of the law, and political dissension at home. Upset by the failure of his policies, the 65-year-old Jefferson looked forward to his retirement: “Never did a prisoner, released from his chains, feel such relief as I shall on shaking off the shackles of power.”

The problem of defending American rights on the high seas now fell to Jefferson’s hand-picked successor, James Madison. In 1809, Congress replaced the failed embargo with the Non-Intercourse Act, which reopened trade with all nations except Britain and France. Then in 1810, Congress replaced the Non-Intercourse Act with a new measure, Macon’s Bill No. 2. This policy reopened trade with France and Britain. It stated, however, that if either Britain or France agreed to respect America’s neutral rights, the United States would immediately stop trade with the other nation.

Napoleon seized on this new policy in an effort to entangle the United States in his war with Britain. He announced a repeal of all French restrictions on American trade. Even though France continued to seize American ships and cargoes, President Madison snapped at the bait. In early 1811, he cut off trade with Britain and recalled the American minister.

For nineteen months, the British went without American trade. Food shortages, mounting unemployment, and increasing inventories of unsold manufactured goods finally convinced Britain to end their restrictions on American trade. But the decision came too late. On June 1, 1812, President Madison asked Congress for a declaration of war. A divided House and Senate concurred. The House voted to declare war on Britain by a vote of 79 to 49; the Senate by a vote of 19 to 13.

A Second War of Independence

Why did the United States declare war on Britain in 1812? The most loudly voiced grievance was British interference with American rights on the high seas. “Free Trade and Sailors’ Rights” was a popular battle cry.

But if British harassment of American shipping was the primary motivation for war, why then did the pro-war majority in Congress come largely from the South, the West, and the frontier, and not from Northeastern ship owners and sailors?

Northeastern Federalists regarded war with Britain as a grave mistake. The United States, they feared, could not hope to successfully challenge British supremacy on the seas and the government could not finance a war without bankrupting the country.

Southerners and Westerners, in contrast, were eager to avenge British insults against American honor. Many Westerners and Southerners had their eye on expansion, viewing war as an opportunity to add Canada and Spanish-held Florida to the United States.

War with Britain also offered another incentive: the possibility of clearing western lands of Indians by removing the Indians’ strongest ally—the British. In late 1811, General William Henry Harrison provoked a fight with an Indian alliance at Tippecanoe Creek in Indiana. Since British guns were found on the battlefield, many Americans concluded that Britain was responsible for the incident.

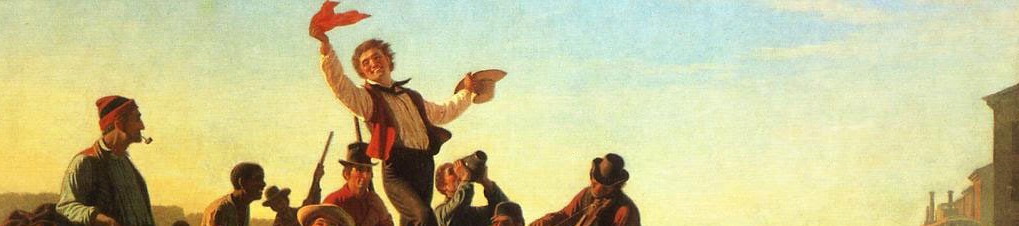

Weary of Jefferson and Madison’s policy of economic coercion, voters swept 63 out of 142 representatives out of Congress in 1810 and replaced them with young Republicans that Federalists dubbed “War Hawks.” Having grown up on tales of heroism during the American Revolution, second-generation Republicans were eager to prove their manhood in a “second war of independence.”

The War of 1812

The United States was woefully unprepared for war. The army consisted of fewer than 7,000 soldiers, few trained officers, and a navy with six warships. In contrast, Britain had nearly 400 warships.

The American strategy called for a three-pronged invasion of Canada and heavy harassment of British shipping. The attack on Canada, however, was a disastrous failure. At Detroit, 2,000 American troops surrendered to a much smaller British and Indian force. An attack across the Niagara River, near Buffalo, resulted in 900 American prisoners of war. Along Lake Champlain, a third army retreated into American territory after failing to cut undefended British supply lines.

In 1813, America suffered new failures, including the defeat and capture of the American army in the swamps west of Lake Erie. Only a series of unexpected victories at the end of the year raised American spirits. On September 10, 1813, America won a major naval victory at the Battle of Lake Erie near Put-in-Bay at the western end of Lake Erie. There, Master-Commandant, Oliver Hazard Perry, who had built a fleet at Presque Isle (Erie, Pennsylvania) successfully engaged six British ships. Though Perry’s flagship, the Lawrence, was disabled in the fighting, he went on to capture the British fleet. He reported his victory with the stirring words, “We have met the enemy and they are ours.”

The Battle of Lake Erie was America’s first major victory of the war. It forced the British to abandon Detroit and to retreat toward Niagara. On October 5, 1813, Major General William Henry Harrison overtook the retreating British army and their Indian allies at the Thames River. He won a decisive victory in which the Indian leader Tecumseh was killed, thereby ending the fighting strength of the northwestern Indians.

In the spring of 1814, Britain defeated Napoleon in Europe, freeing 18,000 veteran British troops to participate in an invasion of the United States. The British planned to invade the United States at three points: upstate New York across the Niagara River and Lake Champlain, the Chesapeake Bay, and New Orleans. The London Times expressed the confident English mood: “Oh, may no false liberality, no mistaken lenity, no weak and cowardly policy interpose to save the United States from the blow! Strike! Chastise the savages, for such they are…Our demands may be couched in a single word—Submission!”

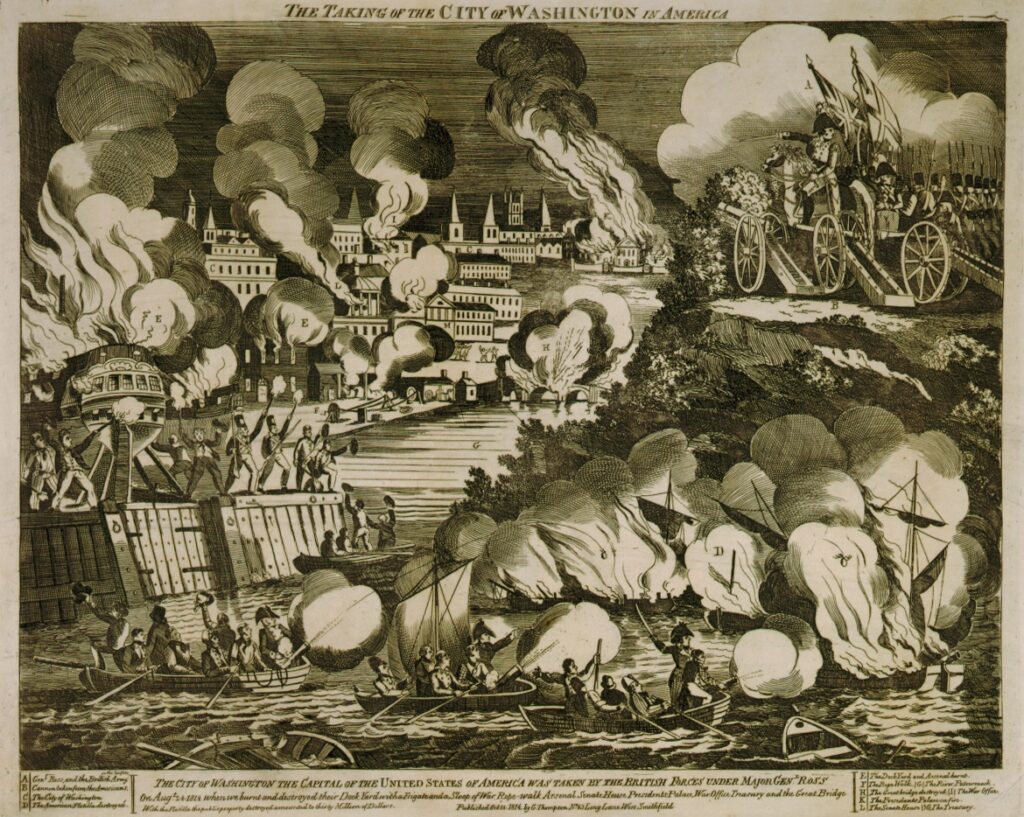

At Niagara, however, American forces, outnumbered more than three to one, halted Britain’s invasion from the north. Britain then landed 4,000 soldiers on the Chesapeake Bay coast and marched on Washington, D.C., where untrained soldiers lacking uniforms and standard equipment were protecting the capital. The result was chaos. President Madison narrowly escaped capture by British forces. On August 24, 1814, the British humiliated the nation by capturing and burning Washington, D.C. President Madison and his wife Dolley were forced to flee the capital—carrying with them many of the nation’s treasures, including the Declaration of Independence and Gilbert Stuart’s portrait of George Washington. The British arrived so soon after the president fled that the officers dined on a White House meal that had been prepared for the Madisons and 40 invited guests.

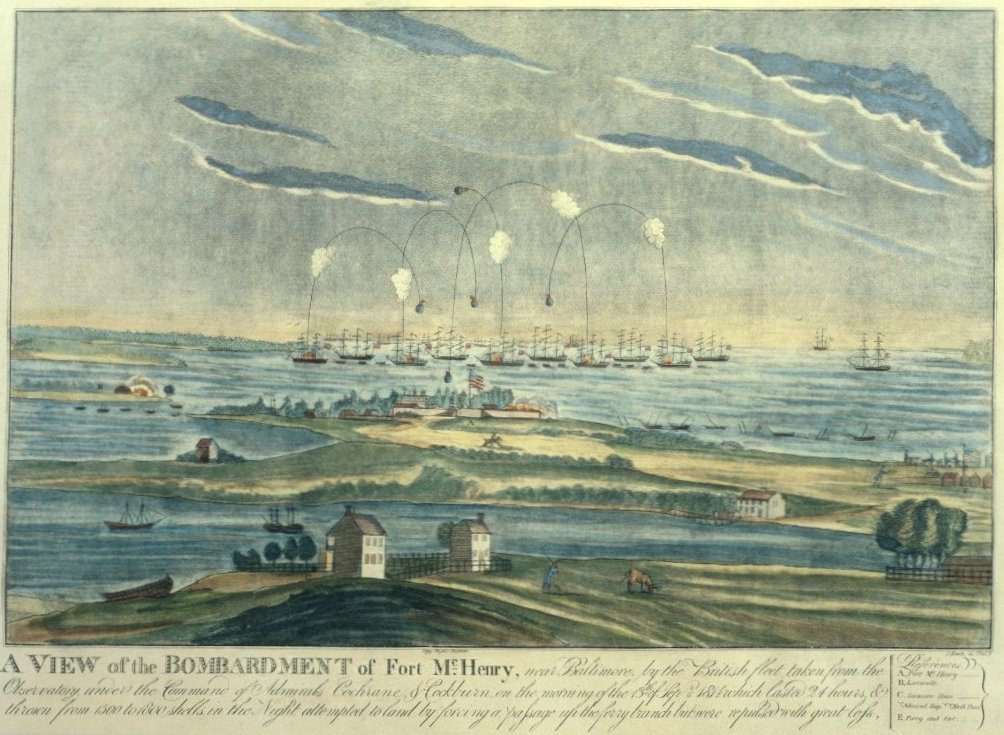

Britain’s next objective was Baltimore. To reach the city, British warships had to pass the guns of Fort McHenry, manned by 1,000 American soldiers. Waving atop the fort was the largest garrison flag ever designed—30 feet by 42 feet. On September 13, 1814, British warships began a 25-hour bombardment of Fort McHenry. British vessels anchored two miles off shore—close enough so that their guns could hit the fort, but too far for American shells to reach them. All through the night British cannons bombarded Fort McHenry, firing between 1,500 and 1,800 cannon balls at the fort. In the light of the “rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air,” Francis Scott Key, a young lawyer detained on a British ship, saw the American flag waving over the fort. At dawn on September 14, he saw the flag still waving. The Americans had repulsed the British attack, with only four soldiers killed and twenty-four wounded.

Key was so moved by the American victory that he wrote a poem entitled “The Star-Spangled Banner” on the back of an old envelope. The song was destined to become the young nation’s national anthem.

The country still faced grave threats in the South. On January 8, 1815, the British fleet and a battle-tested 10,000-man army finally attacked New Orleans. To defend the city, General Andrew Jackson assembled a ragtag army, including French pirates, Choctaw Indians, western militia, and freed slaves. Although British forces outnumbered Americans by more than two to one, American artillery and sharpshooters stopped the invasion. American losses totaled only eight dead and thirteen wounded, while British casualties were 2,036.

Ironically, American and British negotiators in Ghent, Belgium, had signed the peace treaty ending the War of 1812 two weeks earlier. Britain, convinced that the American war was so difficult and costly that nothing would be gained from further fighting, agreed to return to the conditions that existed before the war. Left unmentioned in the peace treaty were the issues over which Americans had fought the war—impressment and British interference with

The War’s Significance

Although often treated as a minor footnote to the bloody European war between France and Britain, the War of 1812 was crucial for the United States. First, it effectively destroyed the Indians’ ability to resist American expansion east of the Mississippi River. General Andrew Jackson crushed the Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in Alabama, while General William Henry Harrison defeated Indians in the Old Northwest at the Battle of the Thames. Abandoned by their British allies, the Indians reluctantly ceded most of their lands north of the Ohio River and in southern and western Alabama to the U.S. government.

Second, the war allowed the United States to rewrite its boundaries with Spain and solidify control over the lower Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico. Although the United States did not defeat the British Empire, it had fought the world’s strongest power to a draw. Spain recognized the significance of this fact, and in 1819 Spanish leaders abandoned Florida and agreed to an American boundary running clear to the Pacific Ocean.

Third, the Federalist Party never recovered from its opposition to the war. Many Federalists believed that the War of 1812 was fought to help Napoleon in his struggle against Britain, and they opposed the war by refusing to pay taxes, boycotting war loans, and refusing to furnish troops. In December 1814, delegates from New England gathered in Hartford, Connecticut, where they recommended a series of constitutional amendments to restrict the power of Congress to wage war, to regulate commerce, and to admit new states. The delegates also supported a one-term president (in order to break the grip of Virginians on the presidency) and the abolition of the Three-fifths clause in the Constitution (which increased the political clout of the South), and talked of seceding if they did not get their way.

The proposals of the Hartford Convention became public knowledge at the same time as the terms of the Treaty of Ghent and the American victory in the Battle of New Orleans. Euphoria over the war’s end led many people to brand the Federalists as traitors. The party never recovered from this stigma and disappeared from national politics.

The War of 1812 also carried profound consequences for the nation’s economic development. With foreign trade curtailed, New Englanders began to invest in cotton mills, marking the beginning of America’s industrial revolution. The war also prompted New Englanders to embark a prolonged campaign to elevate the nation’s moral values. New Englanders took the lead in a host of reform efforts: to suppress drinking, establish public schools, build penitentiaries and insane asylums, and abolish slavery.