The Jeffersonian Era

The Jeffersonian Era

As president, Thomas Jefferson sought to implement his Republican principles, including a frugal, limited government, respect for states’ rights, and encouragement for agriculture. He cut military expenditures, paid off the public debt, and repealed many taxes. His most important act was the purchase of Louisiana Territory, which nearly doubled the size of the nation.

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court established the principle of judicial review, which enables the courts to review the constitutionality of federal laws and to invalidate acts of Congress when they conflict with the Constitution.

The Jeffersonian era was marked by severe foreign policy challenges, including harassment of American shipping by North African pirates and by the British and French. In an attempt to stave off war with Britain and France, the United States attempted various forms of economic coercion. But in 1812—to protect American shipping and seamen, to clear western lands of Indians, and to preserve national honor—the county once again waged war with Britain, fighting the world’s strongest power to a stalemate.

Jefferson in Power

Thomas Jefferson’s goal as president was to restore the principles of the American Revolution. Not only had the Federalists levied oppressive taxes, stretched the provisions of the Constitution, and established a bastion of wealth and special privilege in the creation of a national bank, they also had subverted civil liberties and expanded the powers of the central government at the expense of the states. A new revolution was necessary, “as real a revolution in the principles of our government as that of 1776 was in its form.” What was needed was a return to basic republican principles.

On March 4, 1801, Jefferson, clad in clothes of plain cloth, walked from a nearby boarding house to the new United States Capitol in Washington. Without ceremony, he entered the Senate chamber, and took the presidential oath of office. Then, in a weak voice, he delivered his inaugural address—a classic statement of Republican principles.

His first concern was to urge conciliation and to allay fear that he planned a Republican reign of terror. “We are all Republicans,” he said, “we are all Federalists.” Echoing George Washington’s Farewell Address, he asked his listeners to set aside partisan and sectional differences and remember that “every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle.” Only a proper respect for principles of majority rule and minority rights would allow the new nation to thrive. In the remainder of his address he laid out the principles that would guide his presidency:

- a frugal, limited government

- reduction of the public debt

- respect for states’ rights

- encouragement of agriculture

- a limited role for government in peoples’ lives

He committed his administration to repealing taxes, slashing government expenses, cutting military expenditures, and paying off the public debt. Through his personal conduct and public policies he sought to return the country to the principles of Republican simplicity. He introduced the custom of having guests shake hands instead of bowing stiffly and placed dinner guests at a round table, so that no individual would have to sit in a more important place than any other. Jefferson refused to ride an elegant coach or host elegant dinner parties and balls and wore clothes made of homespun cloth. To dramatize his disdain for pomp and pageantry, he received the British minister in his dressing gown and slippers.

Jefferson believed that presidents should not try to impose their will on Congress, and consequently he refused to openly initiate legislation or to veto congressional bills on policy grounds. Convinced that Presidents Washington and Adams had acted like British monarchs by personally appearing before Congress and requesting legislation, Jefferson simply sent Congress written messages. It would not be until the presidency of Woodrow Wilson that another president would publicly address Congress and call for legislation.

Jefferson’s commitment to Republican simplicity was matched by his stress on economy in government. He slashed army and navy expenditures, cut the budget, eliminated taxes on whiskey, houses, and slaves, and fired all federal tax collectors. He reduced the army to 3,000 soldiers and 172 officers, the navy to six frigates, and foreign embassies to three in Britain, France, and Spain.

Convinced that ownership of land and honest labor in the earth were the firmest bases of Republican government, Jefferson convinced Congress to cut the price of public lands and to extend credit to purchasers in order to encourage land ownership and rapid western settlement. A firm believer in the idea that America should be the “asylum” for “oppressed humanity,” he persuaded Congress to reduce the residence requirement for citizenship from fourteen to five years. To ensure that the public knew the names and number of all government officials, Jefferson ordered publication of a register of all federal employees.

Contemporaries were astonished by the sight of a president who had renounced all the practical tools of government: an army, a navy, and taxes. Jefferson’s goal was, indeed, to create a new kind of government, a Republican government wholly unlike the centralized, corrupt, patronage-ridden one against which Americans had rebelled in 1776.

War on the Judiciary

When Thomas Jefferson took office, not a single Republican served as a federal judge. He feared that the Federalists intended to use the courts to frustrate Republican plans.

The first goal of his presidency was to weaken Federalist control of the federal judiciary. The specific issue that provoked his anger was the Judiciary Act of 1801, which was passed by the lame-duck Federalist-dominated Congress five days before Adams’s term expired. The law created sixteen new federal judgeships, positions which President Adams promptly filled with Federalists. The Act reduced the number of Supreme Court justices effective with the next vacancy, delaying Jefferson’s opportunity to name a new Supreme Court justice.

Jefferson’s supporters in Congress repealed the Judiciary Act. William Marbury, who had been appointed to a judgeship by President Adams during his last hours of office, filed suit. Marbury asked the Supreme Court to order the Jefferson administration to give him a formal letter of appointment.

The case threatened a direct confrontation between the judiciary and the executive and legislative branches of the federal government. If the Supreme Court ordered Madison to give Marbury his judgeship, then the Jefferson administration was likely to ignore the court.

John Marshall, the new chief justice of the Supreme Court, was well aware of the court’s predicament. When Marshall became the nation’s fourth chief justice in 1801, the Supreme Court lacked prestige and public respect. Presidents found it difficult to find willing candidates to serve as justices. The Court was considered so insignificant that it held its sessions in a clerk’s office in the basement of the Capitol and only met six weeks a year.

In his opinion in Marbury v. Madison, the chief justice ingeniously expanded the court’s power without directly provoking the Jeffersonians. Marshall conceded that Marbury had a right to his appointment but ruled the Court had no authority to order the Jefferson administration to act, since the section of the Judiciary Act that gave the Court the power to issue an order was unconstitutional. For the first time, the Supreme Court had declared an act of Congress unconstitutional.

Marbury v. Madison was a landmark in American constitutional history. The decision established the power of the federal courts to review the constitutionality of federal laws and to invalidate acts of Congress when they are determined to conflict with the Constitution. This power, known as judicial review, provides the basis for the important place that the Supreme Court occupies in American life today.

In fact, the Supreme Court did not invalidate another act of Congress for half a century. Chief Justice Marshall recognized that the judiciary was the weakest of the three branches of government, and in the future the high court refrained from rulings in advance of national sentiment.

Marshall’s decision in Marbury v. Madison intensified Republican party distrust of the courts. Impeachment, Jefferson believed, was the only way to make the courts responsive to the public will. Federalists responded by accusing the administration of endangering the independence of the federal judiciary.

Three weeks before the court handed down its decision in Marbury v. Madison, the Republican-controlled Congress impeached and removed from office a federal district court judge, John Pickering, who was an alcoholic and may have been insane.

On the day of Pickering’s conviction, the House voted to impeach Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase, who had accused the Jeffersonians of being atheists. Chase was put on trial for holding opinions “hurtful to the welfare of the country.” The Constitution specified that a judge could only be removed from office for “treason, bribery, or other high crimes,” and in a historic decision that helped to guarantee the independence of the judiciary, the Senate voted to acquit Chase. “Impeachment is a farce which will not be tried again,” Jefferson announced.

Since Chase’s acquittal, no further attempts have been made to reshape the federal courts through impeachment. Despite the Republicans’ active hostility toward an independent judiciary, the Supreme Court had emerged as a vigorous third branch of government.

The Louisiana Purchase

In 1800, Spain secretly ceded the Louisiana territory—the area stretching from Canada to the Gulf Coast and from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains—to France, which closed the port of New Orleans to American farmers. Westerners, left without a port from which to export their goods, exploded with anger. Many demanded war.

The prospect of French control of the Mississippi River alarmed Jefferson. Jefferson feared the establishment of a French colonial empire in North America blocking American expansion. The President sent negotiators to France, with instructions to purchase New Orleans and as much of the Gulf Coast as they could for $2 million.

Circumstances played into American hands when France failed to suppress a slave rebellion in Haiti. One hundred thousand slaves, inspired by the French Revolution, had revolted, destroying 1,200 coffee and 200 sugar plantations. In 1800, France sent troops to crush the insurrection and reconquer Haiti, but they met a determined resistance led by a former slave named Toussaint Louverture. Then, French forces were wiped out by mosquitoes carrying yellow fever. “Damn sugar, damn coffee, damn colonies,” Napoleon, the French leader, exclaimed. Without Haiti, Napoleon had little interest in keeping Louisiana.

France offered to sell not just New Orleans, but all of Louisiana Province. The American negotiators agreed on a price of $15 million, or about 4 cents an acre. In a single stroke, Jefferson doubled the size of the country.

To gather information about the geography, natural resources, wildlife, and peoples of Louisiana, President Jefferson dispatched an expedition led by his private secretary Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, a Virginia-born military officer. For 2 years Lewis and Clark led some thirty soldiers and ten civilians up the Missouri River as far as present-day central North Dakota and then west to the Pacific.

Conspiracies

The acquisition of Louisiana terrified many Federalists, who feared that the creation of new western states would further dilute their political influence. In the winter of 1803-1804, a group of Federalist congressmen plotted to establish a “Northern Confederacy” consisting of New Jersey, New York, New England, and Canada, to be established with the support of Britain.

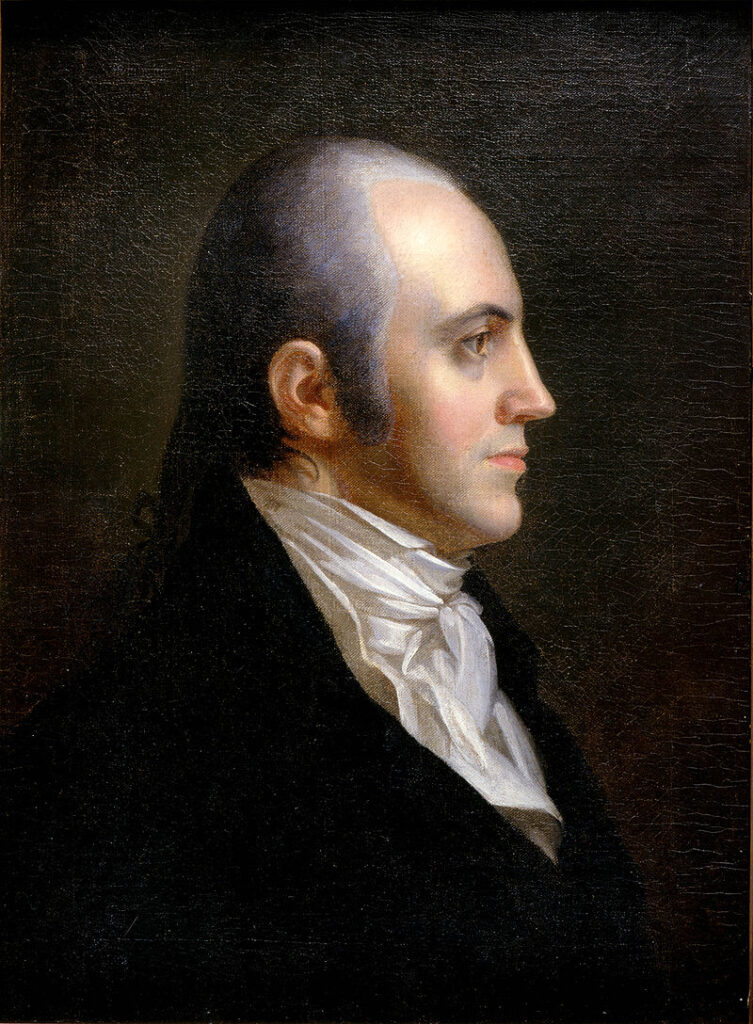

Alexander Hamilton repudiated this scheme, and the conspirators turned to Vice President Aaron Burr. In return for Federalist support in his campaign for the governorship of New York, Burr was to swing New York into the Northern Confederacy. Burr was badly beaten, in part because of Hamilton’s opposition. Incensed and irate, Burr challenged Hamilton to the duel in which the former Treasury Secretary was fatally wounded.

Burr was now a ruined politician and a fugitive from the law. In debt, on the edge of bankruptcy, his fortunes at their lowest point, the desperate Burr became involved in a conspiracy for which he would be put on trial for treason.

In the fall of 1806, Burr and some sixty schemers traveled down the Ohio River toward New Orleans. Their precise goal remains unknown, since Burr told different stories to various people. Spain’s minister believed that Burr planned to set up an independent nation in the Mississippi Valley. Others reported that he planned to seize Spanish territory in what is now Texas, California, and New Mexico. The British minister was told that for $500,000 and British naval support, Burr would separate the states and territories west of the Appalachians from the rest of the Union and create an empire with himself as its head.

One of Burr’s co-conspirators, James Wilkinson, commander of U.S. forces in the Southwest, recognized that the scheme was doomed to failure. Wilkinson sent a letter to President Jefferson betraying Burr.

Burr fled, but was apprehended in Mississippi Territory. He was then taken to the Richmond, Virginia, circuit court, where, in 1807, he was tried for treason. Jefferson, convinced that Burr was a dangerous man, wanted a conviction regardless of the evidence. Chief Justice John Marshall, who presided over the trial, was equally eager to discredit Jefferson.

Ultimately, Burr was acquitted. The reason for the acquittal was the Constitution’s strict definition of treason as “levying war against the United States” or “giving…aid and comfort” to the nation’s enemies. In addition, each overt act of treason had to be attested to by two witnesses. The prosecution was unable to meet this strict standard, and as a result of Burr’s acquittal, few future cases of treason have ever been tried in the United States.

Was Burr guilty of conspiring to separate the West by force? Probably not. The prosecution’s case was extremely weak. It rested largely on the unreliable testimony of Wilkinson, Burr’s co-conspirator, who was a spy in the way of Spain while serving as a U.S. Army commander.

What, then, was the purpose of Burr’s scheming? It appears likely that the former Vice President was planning a filibuster expedition—an unauthorized military attack on Mexico, which was then controlled by Spain. To the end of his life, Burr denied that he had plotted treason against the United States. Asked by one of his closest friends whether he had sought to separate the West from the rest of the nation, Burr responded with an emphatic “No! I would as soon have thought of taking possession of the moon and informing my friends that I intended to divide it among them.”

History Through…

… Primary Sources: An Affair of Honor

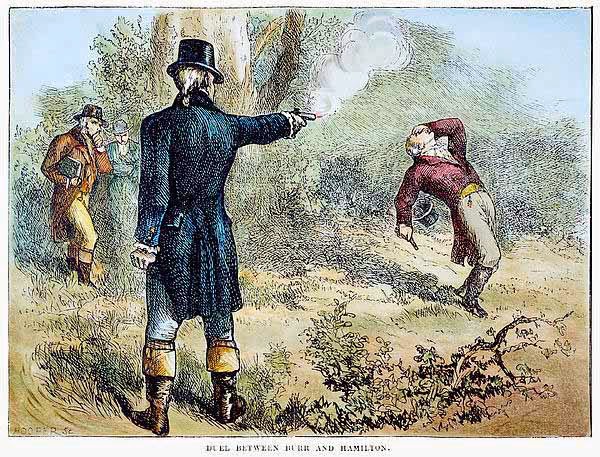

On the morning of June 18, 1804, a visitor handed a package to the former Treasury Secretary, Alexander Hamilton. Inside, was a newspaper clipping and a terse three-sentence letter. The clipping said that Hamilton had called Vice President Aaron Burr “a dangerous man, and one who ought not to be trusted with the reins of government.” It went on to say that Hamilton had “expressed” a “still more despicable opinion” of Burr—apparently a bitter personal attack on Burr’s private morality. The letter, signed by Burr, demanded a “prompt and unqualified” denial or an immediate apology.

Alexander Hamilton regarded Burr as an unscrupulous man. Burr, in turn, blamed Hamilton for his defeat in the race for Governor of New York earlier in the year. When Hamilton failed to respond to his letter satisfactorily, Burr insisted that they settle the dispute according to the code of honor.

Gentlemen in late eighteenth-century America were very anxious to protect their honor. To defend his reputation, a gentleman might challenge another to a duel, which was followed by a series of formal responses and negotiations. Only rarely did a challenge result in violence. Eleven times Alexander Hamilton was involved in affairs of honor, but only once were shots exchanged.

Shortly after seven o’clock on the morning of July 11, 1804, Burr and Hamilton met on a dueling ground in New Jersey, across the Hudson River from New York. It was the exact spot where Hamilton’s eldest son Philip had died in an earlier duel.

After he and Burr took their positions ten paces apart, Hamilton raised his pistol on the command to “Present!” and fired. His shot struck a tree a few feet to Burr’s side. Then Burr fired. His shot struck Hamilton in the right side and passed through his liver. Hamilton died the following day.

Hamilton had said he was going to intentionally fire his first shot to the side. The popular view was that Burr had slain the Federalist leader in an act of cold-blooded murder. In fact, historians do not know whether Burr was guilty of willful murder. According to the code of honor, if Burr missed on his first try, Hamilton would have a second chance to shoot.

New Jersey indicted Burr for murder. The Vice President took refuge in Georgia and South Carolina, until the indictments were quashed and he could finish his term in office.

Read Hamilton’s statement—written between June 27 and July 4, 1804 to be made public in the event of his death.

Statement on Impending Duel with Aaron Burr

New York, June 28–July 10, 1804

On my expected interview with Col Burr, I think it proper to make some remarks explanatory of my conduct, motives and views.

I am certainly desirous of avoiding this interview, for the most cogent reasons.

1. My religious and moral principles are strongly opposed to the practice of Duelling, and it would even give me pain to be obliged to shed the blood of a fellow creature in a private combat forbidden by the laws.

2. My wife and Children are extremely dear to me, and my life is of the utmost importance to them, in various views.

3. I feel a sense of obligation towards my creditors; who in case of accident to me, by the forced sale of my property, may be in some degree sufferers. I did not think my self at liberty, as a man of probity, lightly to expose them to this hazard.

4. I am conscious of no ill-will to Col Burr, distinct from political opposition, which, as I trust, has proceeded from pure and upright motives.

Lastly, I shall hazard much, and can possibly gain nothing by the issue of the interview.

But it was, as I conceive, impossible for me to avoid it. There were intrinsick difficulties in the thing, and artificial embarrassments, from the manner of proceeding on the part of Col Burr.

Intrinsick—because it is not to be denied, that my animadversions on the political principles character and views of Col Burr have been extremely severe, and on different occasions, I, in common with many others, have made very unfavourable criticisms on particular instances of the private conduct of this Gentleman.

In proportion as these impressions were entertained with sincerity and uttered with motives and for purposes, which might appear to me commendable, would be the difficulty (until they could be removed by evidence of their being erroneous), of explanation or apology. The disavowal required of me by Col Burr, in a general and indefinite form, was out of my power, if it had really been proper for me to submit to be so questionned; but I was sincerely of opinion, that this could not be, and in this opinion, I was confirmed by that of a very moderate and judicious friend whom I consulted. Besides that Col Burr appeared to me to assume, in the first instance, a tone unnecessarily peremptory and menacing, and in the second, positively offensive. Yet I wished, as far as might be practicable, to leave a door open to accommodation. This, I think, will be inferred from the written communications made by me and by my direction, and would be confirmed by the conversations between Mr van Ness and myself, which arose out of the subject.

I am not sure, whether under all the circumstances I did not go further in the attempt to accommodate, than a pun[c]tilious delicacy will justify. If so, I hope the motives I have stated will excuse me.

It is not my design, by what I have said to affix any odium on the conduct of Col Burr, in this case. He doubtless has heard of animadversions of mine which bore very hard upon him; and it is probable that as usual they were accompanied with some falsehoods. He may have supposed himself under a necessity of acting as he has done. I hope the grounds of his proceeding have been such as ought to satisfy his own conscience.

I trust, at the same time, that the world will do me the Justice to believe, that I have not censured him on light grounds, or from unworthy inducements. I certainly have had strong reasons for what I may have said, though it is possible that in some particulars, I may have been influenced by misconstruction or misinformation. It is also my ardent wish that I may have been more mistaken than I think I have been, and that he by his future conduct may shew himself worthy of all confidence and esteem, and prove an ornament and blessing to his Country.

As well because it is possible that I may have injured Col Burr, however convinced myself that my opinions and declarations have been well founded, as from my general principles and temper in relation to similar affairs—I have resolved, if our interview is conducted in the usual manner, and it pleases God to give me the opportunity, to reserveand throw away my first fire, and I have thoughts even of reserving my second fire—and thus giving a double opportunity to Col Burr to pause and to reflect.

It is not however my intention to enter into any explanations on the ground. Apology, from principle I hope, rather than Pride, is out of the question.

To those, who with me abhorring the practice of Duelling may think that I ought on no account to have added to the number of bad examples—I answer that my relative situation, as well in public as private aspects, enforcing all the considerations which constitute what men of the world denominate honor, impressed on me (as I thought) a peculiar necessity not to decline the call. The ability to be in future useful, whether in resisting mischief or effecting good, in those crises of our public affairs, which seem likely to happen, would probably be inseparable from a conformity with public prejudice in this particular.